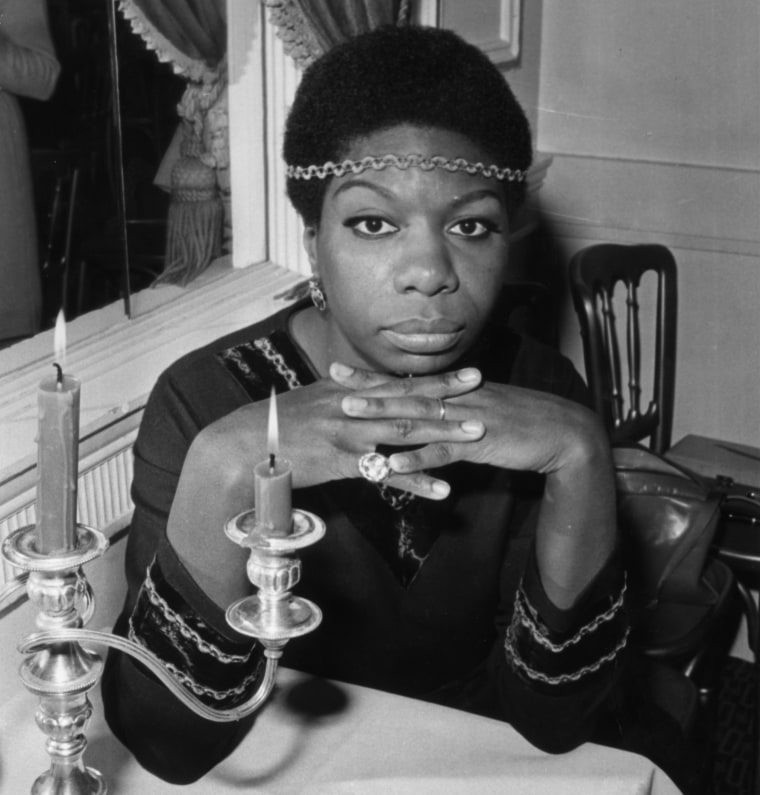

Nina Simone

Ian Showell / Stringer

Nina Simone

Ian Showell / Stringer

On April 14, 2018, Nina Simone will be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, making her the 16th solo woman to be honored in the Performers category since the very first induction ceremony in 1986. Broaden the list to include all-women groups and bands led by women, and Simone becomes the 28th woman act to be ranked among Rock Hall performers. An overwhelming majority — 87 percent — of the 220 inductees to date have been men, or bands led by men. That Simone's induction comes 60 years after the release of her 1958 debut album, 32 years after the first Rock Hall induction (for which she was eligible), and 15 years after her death indicates a longstanding aversion to including women performers in the Rock Hall.

There have never been more than two women acts inducted in the Performers category in a given year; in 2016, no women were inducted at all, and Cheap Trick, Chicago, and Deep Purple all made the cut over Janet Jackson, who was shortlisted. The long list of male acts inducted before Nina Simone, whose influence still shudders throughout contemporary pop music, includes Aerosmith, AC/DC, Journey, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Simone's induction feels long overdue, but she is not the first woman performer to be included in the Rock Hall decades after she became eligible. (An act becomes eligible for induction 25 years after the release of its first commercial recording.) Joan Baez, inducted in 2017, had similarly met the requirements since the ceremony's founding year. On average, solo women, all-women groups, and women-led bands wait 10.5 years after their first year of eligibility to be honored in the Rock Hall Performers category. Only a handful have been inducted within five years of their becoming eligible, and none have been ushered into the Rock Hall on their first year of eligibility, as Nirvana was in 2014.

“The Rock Hall still clings to a patriarchal view of whose music registers as historically noteworthy.”

The Rock Hall, like the Grammys (who notably rewarded an exceptionally mellow Beck album over an exceptionally adventurous Beyoncé album in 2015), still clings to a patriarchal view of whose music registers as historically noteworthy. "Something was coded into the DNA of rock & roll at its outset — into the very music culture that women are remaking today: the idea that girls matter, but only because of what they inspire men to do," writes NPR's Ann Powers in a recent essay. Since Elvis, the idea that men make rock and women consume it has guided canonization, whose extension to key women figures has been limited. Though certain Rock Hall inductees have landed at the edge of what might be considered "rock & roll" — pop, country, and most recently hip-hop all have representatives among the honorees — a staid percentage of the Rock Hall's Performers are groups of three to five white men. In 2018, the Performers inductees are Nina Simone and four groups of white men; in 2017, the inductees were Tupac, Joan Baez, and three groups of white men. Whatever honors get bestowed on artists outside a traditionalist rock mold seem tentatively meted out; on artists within that mold, the same honors are lavished.

Though 2018 will mark the first year a white man is not up for Album of the Year at the Grammys, the category carries as much gender imbalance as the next class of Rock Hall performers. Of the five nominees, only one album, Lorde’s Melodrama, was made by a woman. That Lorde, like Simone, is alone (and not joined by SZA, who enjoys Grammy nominations in plenty of other categories) points to a series of nominations shaped more by reactionary gatekeeping than the rewarding of risk or the rewriting of pop mythology. It also may point to the way power in the music industry has been shaking out along gender lines. Few men can touch Adele, Taylor Swift, or Beyoncé when it comes to moving albums or dominating a news cycle. Though men dominated 2017 on the Billboard charts, male musicians's commercial power is more diffuse, spread out among players like Ed Sheeran, Bruno Mars, Drake, and Kendrick Lamar.

Women earn money and attention from listeners and awards committees; it's just that fewer of them tend to accumulate more of it apiece. Perhaps this looks like equality. A popular refrain among those who might disavow misogyny's effects in the music business is that Beyoncé is very successful. But for the Grammys, the Rock Hall, and other institutions who guard canonization to reinforce this consolidation — for them to imply that one honored woman balances out the honoring of four men sends a clear message. It says, Women are not needed here, not the way men are. Their inclusion in the canon is not urgent. They are already taking up enough space.

"To understand the hold masculine dominance maintains on rock and its antecedents, it's necessary to not simply celebrate how individuals or groups of women have overcome or sidestepped it, but to examine the ways in which messages and behaviors are reinforced," Powers continues in her essay. "That means confronting the givens of rock and roll: the emotional dynamics presented in the music as natural and fundamental, the roles different players can occupy both within fantasy scenarios and in real life, the rationalizations and reinforcements that have allowed those roles and customs to survive." Until such presumptions are, in fact, confronted, until the guardians of the canon loosen the parameters on just how much space women get to take up, the accolades bestowed upon women making music will continue to come out in a trickle, not a flood.