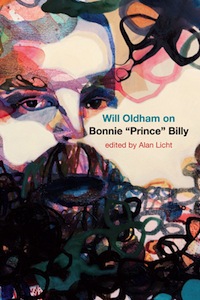

In a massive new book, Alan Licht talks to the singer about his strange musical life.

There aren’t too many people like Will Oldham. As a musician, he’s responsible for making gorgeous and often pained folk music. His voice cracks and moans across plaintive guitar with lived-in, world-weary beauty. He’s also been an actor, shot album covers and generally just popped up in unexpected places his entire career. He’s a compelling figure as much for what we don’t know about him as for what we do. In his massive, self-referential book, Will Oldham on Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, avant-garde musician and writer Alan Licht sat down with Oldham for an all-encompassing conversation about life, anger, R. Kelly and a staggering amount of other topics. An excerpt follows.

Why was Wilding in the West only released in Australia and Japan? Summer in the Southeast was released on Sea Note only, no P-Vine [Japanese label], no Spunk [Australian label], no Domino; Is It the Sea? was Domino [UK]; and then Wilding in the West was the other two territories, so each territory got its own live record. Paul came out and recorded four or five shows, and then we sent all the tapes to [Neil] Hagerty, who mixed it and created a couple of songs [the sound collages “Naked Lion” and “Magnificent Billy”]. There’s definitely some songs that have vocals from multiple nights all on the same song, so there might be a third harmony that existed because someone sang a different part on another night, so two of the same person’s voice.

The Ask Forgiveness EP, a record of covers, was made with Meg Baird and Greg Weeks of the band Espers in 2007. Did the song choices overlap with Meg’s or Greg’s taste or sensibility? No, they didn’t know any of the songs. I sent them demos of me singing the songs, and while we were mixing they would be like, “All right, whose song is this?” “R. Kelly.” “Ha ha, right, OK, no . . . really, whose song is this?” [laughs]

There was one time when Sweeney and I were in California to do a show for a surf-movie festival. They put us up in a hotel in Santa Monica, and we were like, “What the fuck are we gonna do tonight?” We looked in the paper and Espers was playing at McCabe’s, opening for the Incredible String Band. That was the first time I went to McCabe’s since I’d seen Bob Mould there in 1989, so it was kind of rediscovering the place. I’d never seen Espers, only heard about ’em, and it was great, they were so good. I started listening to them, and it was kind of intoxicating every time I heard the first album and the covers record, The Weed Tree, which is amazing.

So was that an inspiration behind trying to do a covers record with Meg and Greg? I think so. Part of it, again, was thinking of an excuse to get to know them and be in the same room with Meg while she was singing, and so I presented the idea of doing an EP of covers and tried to choose songs that would be belly-gazing, self-reflexive, soliloquy-style songs—like, where-am-I-and-how-did-I-get-here kind of songs—but trying to cull them from different musicians who’d been important to me.

What you were saying about the Ramones doing covers was something that had occurred to me about this record anyway: that it fits seamlessly into a lot of the language of your own songs—and the way it’s designed, you don’t know whose song it is unless you look at the CD itself. Actually, we only included songwriter and publisher names; didn’t even include the song titles anywhere on the record artwork. Maybe if you download it, but I don’t think the song titles are on the record anywhere. It’s just the track numbers and then the writer and the publisher, ’cause I didn’t want anyone to think of it as a covers record. I didn’t want them to easily be able to look up the songs by title or to immediately say, “I think I know that song, by that person.” It was just writers whom I figured most people wouldn’t know, but it was enough to give credit to them, which was proper, and force people to do a little bit of research if they liked the song—they could find it in five minutes. But it would ideally be more of a listening experience, and then if you wanted to do more work, you could.

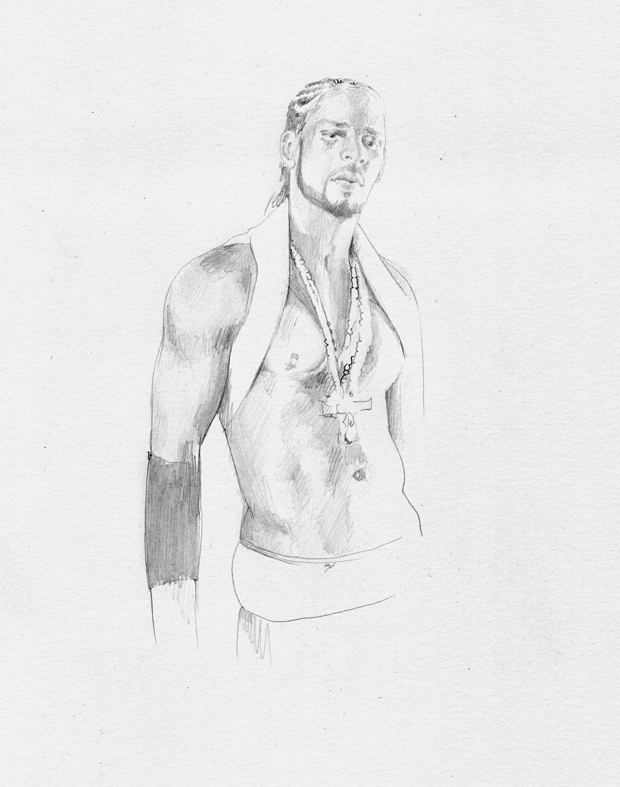

The title comes from “Better to ask forgiveness than permission”; I guess some of those people » would want permission asked to cover their songs? Possibly… and it was intended to be, with some fun, a self-indulgent record, because I was choosing all these self-indulgent songs, so it was [addressed] to the audience as well, not just to the [original writers/performers]. There was that really garish picture on the front: I found the artist’s business card over in Indiana, in a coffee shop, and I was looking for somebody to do this drawing. I called him, and he turned out to be this total wallflower guy that I’d gone to middle school with, and I had no idea he was an artist. All the photos in the artwork are from my trip to India with my mom, and after she’d left, and it’s all pictures from Kashmir and Ladakh, from 1987.

What made you want to include those photos on this release? I think it was that they were pictures of kids. I was just imagining they were a lot older now… and partly imagining a distance that I have, for the most part, yet to cross with making music, which is: no matter how much I’ve done in music and how far I’ve traveled, none of these people have probably ever heard it, and possibly never will; but it’s sort of an underlying goal, in making music—how do you find that one person somewhere in the world, how can you get a song to that person? The distance between me and them remains. As well as that distance, which will never be bridged, there’s the distance between myself and Phil Ochs, myself and Mickey Newbury—because they’re dead—myself and R. Kelly—I met R. Kelly, but still, I’m a fly, I’m a flea, I’m nothing to him. And it’s the idea that there are some distances that probably will never be crossed. Maybe will, but who knows . . .

I read somewhere that you met Glenn Danzig again, and he didn’t remember you from the 1985 Samhain/Maurice tour at all. But you’d thought about him every day since then. Yeah . . . well, maybe not every day, but it was also great. I went there [to the Danzig/Samhain concert] because I did become friends with London May, who was the drummer in Samhain for November-Coming-Fire and the tour that I was on with Maurice, and used to be in Reptile House with Dan Higgs, and we stayed friends since then—he actually came to nursing school in Louisville. He called me, and he was like, “We’re doing this show, do you want to come see the Samhain/Danzig show?” And afterwards he was like, “You gotta say hello to Glenn, you gotta say hello to Glenn.” He’s like, “Glenn, this is Will, do you remember him?” and Glenn goes, “Hey!” but obviously didn’t remember me at all. I told him, “Great show,” and he said, “Thanks a lot, man,” and then, you know… But it reminded me of this story somebody told about being a huge Fall fan and seeing Mark E. Smith randomly in a pub in England, just drinking in the corner, and going up to him and telling him, “Mr. Smith, sorry, just a moment of your time, I really apologize. I just saw you there and I couldn’t not tell you how important you are to me, how important your music is to me, and it is unbelievable just being in the same room with you.” And Mark E. Smith just saying, “Yeah, heard it all before.” And the guy turning around and exclaiming, “Yes!” [laughs] Like, that’s what you would want from your heroes.

Not only did you meet R. Kelly, you appear in episode 15 of his “Trapped in the Closet” video. How did that happen? Nicky Katt, the actor who’s friends with Sweeney, was also friends with [director] Richard Linklater, and somehow Linklater got the idea to ask me to make music for his Fast Food Nation movie. Although it was Nicky who called me first about it, and they were talking about Superwolf. That was the beginning of a series of frustrations with Linklater; I was always asking him about what he wanted, ’cause he was talking about Superwolf but calling me. I was like, “So, do you want me and Matt to do it?”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you want songs?”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you want incidental music?”

“I’m not sure, I don’t know.”

“OK… I’ll get started!”

At one point I ended up going to see a rough cut of Fast Food Nation in Austin, in which the Mexican characters in the movie were watching TV, and the TV showed “Trapped in the Closet,” just in the background. So after it was done and all the notes were given I asked Ann Carli, who was one of the producers, “Why was that in there?”

“How did you even know what that was?”

“I like R. Kelly’s music a lot, and

we covered one of his songs on the Summer in the Southeast tour, ‘Ignition Part One.’ ”

“ ‘Part One’?! I’ll have to tell Rob [Kelly]!”

She called him and told me, “He was so touched.”

Eventually I blew up at Linklater and quit. But coming out of that was the relationship with Ann Carli, who got Dan and me tickets to see R. Kelly in Chicago. We met him, he complimented Dan on his Vans, and I got his autograph—the third of the three autographs I’ve gotten in my life—and took his do-rag wrapper out of the garbage can of his dressing room to keep as a souvenir. Later Ann called when I was in New York, and said, “Rob wants to know if you want to play a part in the next » installment of the “Trapped in the Closet” videos. It would mean coming to Chicago this weekend and shooting.”

So I bought a ticket to fly to Chicago from New York instead of back to Kentucky. Got there, immediately went to a costume fitting, immediately, from the plane, and then that afternoon went over to R. Kelly’s house to rehearse with everybody in the Chocolate Factory, which is his basement studio. Went out to a fancy dinner with R. Kelly and all the cast and crew, including the cinematographer [Jim Denault], who also shot [Kelly Reichardt’s 1993 film] River of Grass, and then the next day we shot all day. And it was mind-blowing.

In this era there were three “sea” songs—“My Home Is the Sea,” “Death in the Sea,” and “Is It the Sea?” Can you talk about how the sea came to figure so heavily in these songs? Well, “Is It the Sea?” is written by Inge Thomson, from Harem Scarem, but she did write it specifically for our collaboration, in what I think is a perfect songwriter move, a perfect songwriter approach: to write a song for a singer that in form and content is related to the intended singer’s life and work. I think at one point she writes, “Fifteen years have passed,” and I always felt, when singing the song, for her it was a metaphor for touring and playing music in the way that we do. And basically when we did that song 15 years had passed since I started making records. My reading of it was that it was a song about participating in music; she’s talking about work, work and music, the sea being the life of someone who’s out of society and working in the wilds of the sea. And then “Death in the Sea” and “My Home Is the Sea” are more tributes to both the chaos and entropy around nature that many people feel pulled towards, the chaos and entropy that we came from and, for many of us, it’s inevitable that we return to. Some people crave a willful, participatory reentry, or multiple entries and exits, into those wilds, more so than, say, the order of a political system or the order of society. I believe that many people do not know their place in the order of society. I’ve never known my place in the order of society, and therefore have oftentimes found that it was more rewarding or relevant or convenient to associate my drives or my desires with things that exist undeniably and even that dwarf all human endeavor, whether it’s the animal kingdom or our oceans. I would rather be on that team than Team Democracy or Team Society. If you’re careful, you can be welcomed into natural systems, ecosystems, societal systems. But it sometimes feels like it would be more rewarding to be destroyed by a natural ecosystem than it would to be destroyed by a societal system… if you’re going to be destroyed.

I always think that people look ridiculous when they dye their gray hairs away or get face-lifts, and in the same way, when we try to “preserve” our planet, it sometimes has the same non-natural, uncomfortable… it’s like denying that the planet has a life cycle. We exist within the planet and therefore are a part of its life cycle, and we most likely will be part of its destruction in one way or another.

Right—human beings didn’t cause the Ice Age… Yeah, right. And if there’s an ice age coming up, will there be a political party that’s siding for it and one that’s siding against it? There seems to be now with global warming. It’s hard to fathom that people will take the life and health of the planet and make a political issue out of it.

Do you think that man has to serve nature? Nooo!

Do you think that man has to serve nature? Nooo!

Do you think that nature has the upper hand? I think I’ve always been a little mystified by the separation of man from nature, even the green movement and this idea that human beings have destroyed the world—that assumes that we are not of the world. That takes the position that because we can “think,” we have the “responsibility.” To me it seems the ultimate hubris to say that humankind is destroying the world and could save the world, as opposed to saying that we are, in every action that we do, an aspect of the world. So it’s not that it has the upper hand; it’s that we are a tiny subset of the natural order. Some like to say that we are even a force to be reckoned with or recognized, but I don’t believe that we are. I don’t believe that anything human beings do is any more or less significant than anything that a weed or a gust of wind does. I don’t think humankind, throughout history, collectively has done anything that’s any more valuable or important to the development or eventual destruction of what we recognize as the Earth than a sound vibration.

Reprinted from Will Oldham on Bonnie "Prince" Billy, edited by Alan Licht. Copright 2012 by Will Oldham and Alan Licht, with the permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company Inc.