Pete Townsend

/

Pitch Perfect

Pete Townsend

/

Pitch Perfect

One way to tell the story of Will Oldham and Matt Sweeney might involve drawing a web of lines between cover songs. Start with Oldham’s debut album as Palace Brothers, There Is No-One What Will Take Care of You, in 1993, on which he faithfully recreated Washington Phillips’s celestial “I Had a Good Father and Mother,” drag your pen around a 30-year career so thick with allusion and reinterpretation and creativity that Oldham covered himself countless times (Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy Sings Greatest Palace Music was a whole album of Oldham reworking Oldham), and you’ll end up somewhere near the present, with his version of Billie Eilish’s “wish you were gay.” Eilish and her brother Finneas were born years after Oldham released his first record, adding another odd angle to the psychedelic-looking shape on your scrap of paper. And that’s before you consider Sweeney’s old band Chavez’s primal take on the Schoolhouse Rock! song “Little Twelvetoes.”

On Oldham and Sweeney’s triumphant new album, Superwolves — their first together since their debut, Superwolf, released in 2005 and passed around feverishly by acolytes ever since — they cover two songs. One is a spare take on the brutally lonesome “There Must Be a Someone (I Can Turn To),” written by Vern Gosdin and made semi-famous by The Byrds a half-century ago. The other is “I Am a Youth Inclined to Ramble,” a traditional song that can’t be traced back to any specific date but finds its footing in the present day via the Irish folk musician Paul Brady’s arrangement. It tells the story of a young man leaving to find his fortune in America, fearing that his sweetheart won’t be there when he returns.

Maybe it’s too easy to suggest that Oldham and Sweeney saw themselves in the song’s narrator and protagonist, but they have both lived somewhat nomadic lives over the past three decades, leaving their homes and families to tour: sometimes with each other for company, sometimes with other members of a rotating cast, occasionally alone, almost always reveling in the thrilling spontaneity of live performance. And, as they told me on a video call around the album’s release — Sweeney sprawled out on the couch at his apartment in Manhattan, Oldham at the home he shares with his wife and daughter in Louisville — Oldham’s relationship with Brady’s music is only this deep because of a night spent in Dublin some time in the late-’90s, with the radio on and the backstage packed after yet another Bonnie “Prince” Billy show.

What became clear after asking them to talk about the cities that have defined their lives and careers is that Oldham and Sweeney consciously have a reciprocal relationship with space. For every ounce of energy the two have given to the places they’ve passed through in their careers, they know they’ve absorbed just as much. Superwolves approach concert venues, bars, abandoned churches, and studios in the same way that they approach old songs: assessing the energy around them, nodding to the past, and then creating something utterly original.

Porto, Portugal

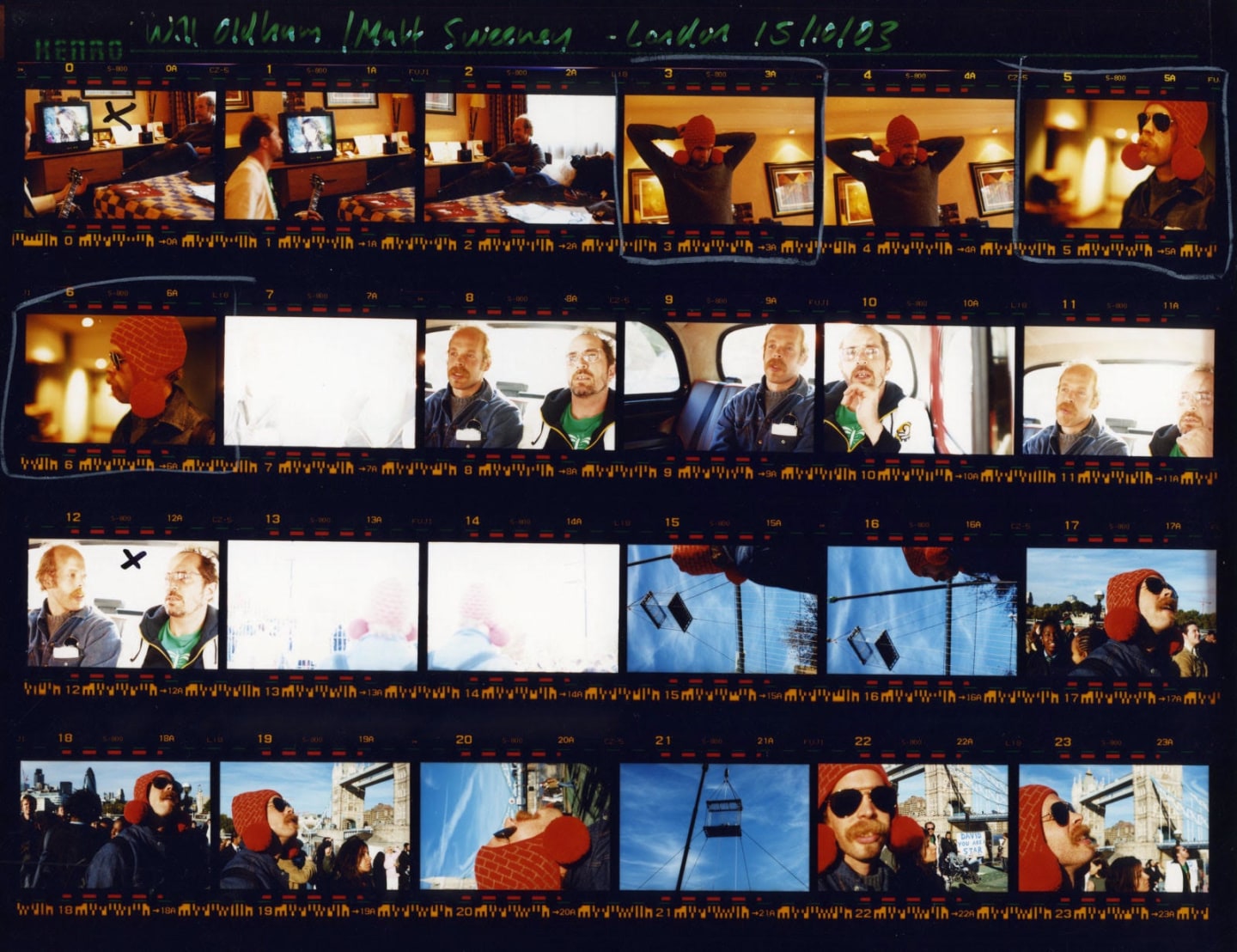

Superwolves in London in 2003, a day or two before traveling to Porto. Contact sheet by Steve Gullick.

Superwolves in London in 2003, a day or two before traveling to Porto. Contact sheet by Steve Gullick.

Oldham and Sweeney travelled to Europe as a duo in October 2003. They played three shows in three nights: two in London and one at Bla Bla in Porto. The three-day mini-tour marked the first time they’d played Superwolf songs live.

Oldham: I remember Porto vividly. It was a good long set, two or three hours. We were just playing more and more songs.

Sweeney: I remember in London, we were on a stage and it was in a theater. But in Porto we were in the middle of a club, it was loose. I think people were excited to see Will by himself, and they didn’t know what the hell I was doing. As I recall, it was fun and I felt like things landed. But that’s what’s fun about it, the whole idea of hearing the songs in real time with other people’s ears as you’re playing them.

Oldham: The energy does the opposite of drop in the room. Some of it will have to do with the songs and some of it will have to do just with the chemistry between you, me, and the audience. It’s an exciting moment to realize that you’re presenting something in a performative way that is hitting home. Nobody’s bringing anything. Nobody’s thinking, “Oh, I know this song.” All they have to react to is the barest things that we’re offering, which are pretty fucking spare. People will respond to it strongly enough that it encourages us to move forward. We have no idea what’s going to happen.

Big Sur, CA

Sweeney and Oldham in Big Sur. Photo by Joanna Newsom

Sweeney and Oldham in Big Sur. Photo by Joanna Newsom

In January 2005, a few days before the release of Superwolf, Oldham and Sweeney were travelling up the West Coast. Between shows at record stores to quietly promote the release, they stopped for a two-night stint at the Fernwood Resort in Big Sur, at the behest of Folk Yeah! founder Britt Govea, who would soon establish himself as a legendary producer who could attract huge artists to intimate and unlikely venues in California.

Oldham: I have really loved to play in places that are great venues, but haven’t been used as great venues or discovered as great venues. And especially that set. We were totally figuring things out, and it’s nice for the audience on that same page. It’s subliminal: “What is this space? What is this music?” Not to feel like, “This is my bar. This is my theater. This is where I go to see music.” To immediately dismantle the idea of an expectation, walk in its discovery: “Okay, now I can approach whatever I’m going to witness with a free and open mind.” Everybody travels to Big Sur because it’s a tiny little settlement. So we are all escaping, and the one thing that we know we’re doing all together is embarking on this musical adventure, the audience and us as performers. We’re in the middle of nowhere.

Matt has a dear old friend, a scientist, who’s based in San Francisco. A constant feature of our trips to San Francisco would be that he would meet us, usually with a test tube or two with a bit of cotton gauze soaked in pharmaceutical-grade ether. And that would be part of our recreational activity during the days that surround a Bay Area appearance. And then we would usually go to Haight Street and go into a head shop and buy some canisters of nitrous, a cracker, and balloons. At Big Sur, in our little motel room, we had one of those dispensers they have in Marx Brothers movies that they use to spray soda water. We’d put the nitrous canister in that and we’d just take our massive hits of the nitrous. We did a couple of really strong rounds of that right before going and playing. And once again that served to completely reset our minds, just clean out all the clutter and the bullshit. All of a sudden it was just: Who am I? Where am I? What am I supposed to do? Play these songs. Is there anything else I need to do in this world? No. Don’t worry about it. We’ll talk about it later. Just play.

Nobody had anywhere to go except be there with us.

Nashville, TN

Sweeney and Oldham recording Superwolves at The Butcher Shoppe in Nashville. Photo by Pete Townsend.

Sweeney and Oldham recording Superwolves at The Butcher Shoppe in Nashville. Photo by Pete Townsend.

Oldham and Sweeney first met sound engineer David “Ferg” Ferguson through Johnny Cash in the early-aughts. Ferguson’s studio, The Butcher Shoppe, became a regular stop for both artists over the years. They recorded all but five of the Superwolves songs with Ferguson at The Butcher Shoppe, which has since closed its doors.

Sweeney: What Nashville has to offer is the people in the studios, playing music in a room together. There’s probably not another place that has as many people who are good at doing that as Nashville. And specifically The Butcher Shoppe, where we were incredibly fortunate to be able to have our Nashville home. That’s all via David Ferguson.

Oldham: Ferg in many ways, physically and spiritually, resembles the Dr. Seuss character The Lorax. It was in Germantown, a neighborhood that was not on anybody’s map when the studio was established. It was this really beautiful wasteland. Was there a slaughterhouse there?

Sweeney: That was a cattle processing plant, that whole place.

Oldham: Just weird old industrial buildings that would be quasi-occupied by transient businesses. And now… the studio closed about a year ago, and just buildings were rising all around it. High-rises were rising. Everywhere you looked. They were thinking about moving the building or maybe just demolishing it so that they could build more high-rises in this zone. But for a while it still was this weird old industrial building where, down in the basement, David Ferguson and Sean Sullivan were bringing Nashville’s greatest living session musicians to have fun and make great music. Even as the city started to develop and overwhelm it.

Understanding it as Music City USA, someone like me would go there and just think, “Well, there’s Ernest Tubb Record Shop and that’s great, but I don’t get it. I don’t see country music anywhere.” It doesn’t feel like a country music place. Because it’s happening inside of people’s office buildings and inside their heads.

I started going when I needed to make a record and David Berman had moved there, and Harmony Korine is from there basically. And started working with this guy, Mark Nevers, and started to get some experience of what session musicians were there and how Nashville really worked and didn’t work.

Ferg brought the city to life for us and brought its history to life for us through encounters with all of his friends, whether they’re musicians or anybody else. And then just taking us to bars, taking us to restaurants, taking us around the city, taking us on drug runs, whatever we needed to do. But we learned why Nashville indeed was Music City and with Ferg’s help, and to some extent with Mark Nevers’s help. We had a passport into that history so that, yeah, we could join the lineage.

Now it doesn’t resemble itself in any way, shape, or form, and many or most of the things that connected Nashville to its past have been overshadowed and or obliterated.

Louisville, KY

Oldham and Sweeney performing at Surface Noise in Louisville, just before recording Superwolves.

Oldham and Sweeney performing at Surface Noise in Louisville, just before recording Superwolves.

Oldham was born and raised in Louisville, and he lives in the city now with his wife, Elsa, and daughter, Poppy. The first Superwolf record was recorded in Shelbyville, about 45 minutes away. Many of the songs from Superwolves were performed for the first time at an intimate show at Louisville’s Surface Noise Records.

Sweeney: Louisville is one of the last few distinctive American cities. If there was a base for Superwolf it would have to be Louisville.

Oldham: I think there are a lot of American cities that have strong identities once you’re in and among them. But I do know that, for whatever reason throughout the 20th century, there was a dedication — a citywide dedication, a bottom-up and top-down dedication — to arts and culture. My generation were the beneficiaries of a lingering legacy. It wasn’t as active by the even mid-to late-’80s, but I think there was an understanding that the arts were vital and were something that could be participated in. The kids I grew up with got engaged with making music, it wasn’t simple rebellion. There was hell of a lot of creativity and expression. It wasn’t just something for kids to do with their spare time to rebel or get their rocks off. It was part of a lineage and it was something serious that you could be engaged with.

Even when they were doing ridiculous things like being a band called The Dickbrains [singer-songwriter Catherine Irwin’s teenage band], they were also taking it very seriously: “I’m in The Dickbrains and this is surreal and ridiculous. That’s why we’re fucking calling it The Dickbrains.” Or my brother’s band, Languid and Flaccid, had a song called “Fire Engines” where they made tons of noise and then would stop and say “fire engines!” and then make more noise. And these were 12-, 13-, 14-year-old people, who are still active. A couple of those guys [Britt Walford and Brian McMahan] formed Slint later and made Spiderland, and people all over the world still listen to that record and are influenced by that record.

Sweeney: When we were rehearsing the songs for that show [at Surface Noise] that night, Steve Albini came over just to hang and to have a snack or something. Will’s daughter and his wife were there too. We were running these songs just to make sure that we didn’t completely fuck them up in front of people, and there’s Steve Albini. We were sitting on beanbag chairs or some shit.

It was pretty wild, playing this music that’s acoustic and it’s pretty. We worked really hard on it, and it’s definitively vulnerable. It seemed to make perfect sense to play that in front of this guy who did [Big Black’s 1987 album] Songs About Fucking, this terrifying kind of Dark Lord figure to me in high school.

Oldham: Being there with my wife, my at-that-time one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, and Steve just sitting in the living room at our house and playing these songs. We were playing a show, essentially, but just for Steve, Poppy, and Elsa. That’s a pretty great representation of as crucial of an audience as one can get.