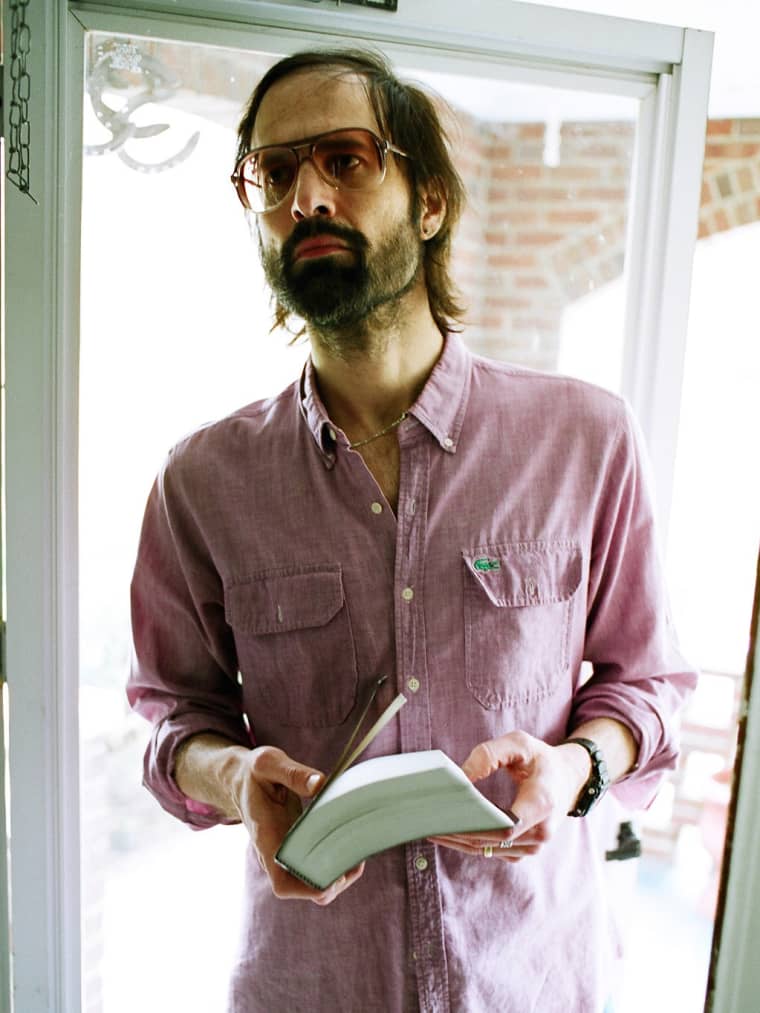

David Berman. Photo by David Berman.

David Berman. Photo by David Berman.

“At night when I have dreams, I lose almost always,” David Berman told The FADER in 2005, in his first ever extended interview. “I’m being betrayed, or left behind, or somehow losing the game. One of the first things I do when I wake up every day is remember that I’m not really losing.” It was 2005, and he’d been clean and sober for nearly two years after attempting suicide by overdosing on Xanax and crack in the Vanderbilt hotel suite where Al Gore watched his presidential candidacy crumble in 2000. A year after the attempt — happy for the first time in years and connecting with Judaism in a way the Silver Jews frontman never had before — he decided he’d died that night and was living in an imaginary future.

But Berman kept on living, releasing his fifth and sixth Silver Jews LPs before taking a decade-long hiatus from music. As he related to Kreative Kontrol’s Vish Khanna in 2019, he initially felt compelled to pick up his guitar after all those years for financial reasons, but he soon found himself writing songs that were, by his own admission, some of his best. With his new band Purple Mountains, he released a gut-wrenching, immediately acclaimed collection of songs about ruined love, overwhelming grief, and unrelenting depression. He hanged himself in a Brooklyn apartment a month later.

Despite the tragic circumstances of his life’s conclusion, David Berman had been winning by everyone’s yardstick but his own since the early ’90s. Though he never achieved the commercial success of his original bandmates, Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich (Pavement’s frontman and drummer, respectively), he developed a cult following that hung on his every word, sung or written. He was married, owned a home, had a dog, published a bestselling book of poetry, and recorded three or four of the best albums of all time.

Berman could write a catchy riff as well as anyone, but his lyrics are what place him in the pantheon of history’s greatest songcrafters. Inspired to varying degrees by Jello Biafra and Emily Dickinson, whose poem “Tell all the truth but tell it slant” became a mantra that echoed across his music, he wrote with stunning wit and heartbreaking clarity. Many of his best lines are slant rhymes — “And when I see her in the park, it barely merits a remark / How we stand the standard distant strangers stand apart,” for instance — but the slant mentality cuts far deeper into the core of his work than that. It’s the uneasy wisdom in his off-color jokes, the shaggy insights lingering at the edges of his simplest statements, the disarming despair of his upbeat marches toward the void.

However tilted their presentation, most of Berman’s songs are self-contained stories, whether their premises are straightforward or absurd, their narratives linear or fragmented. But “Like Like the the the Death,” a late-album cut from Silver Jews’ 1998 masterpiece American Water, follows an internal logic that’s invisible to anyone but its author.

“Like like, the the the death,” Berman begins. “Air, crickets, air, crickets, air, crickets, air crickets, air.” It’s a stuttering start that resists meaning beyond direct association. If death is like air and crickets — or grass and rabbits, as he’ll later intone in the same scansion and melody — it must be a natural, peaceful state.

The verse continues to veer left, as fleeting images like “mother and child with magazine” are set against essential, unanswerable questions like “Why is there something instead of nothing?” Existential inquiries like these exist elsewhere in Berman’s catalog, but rarely are they presented so starkly, without gnarled tufts of references and iconography (“But there’s an altar in the valley / For the things in themselves as they are / And the triumph of the obstacle / And horseleg swastikas”) or self-deprecation (“She’s making friends, I’m turning stranger”).

Photos by Cassie Berman.

Photos by Cassie Berman.

“Folks who’ve watched their mother kill an animal know that their home is surrounded by places to go,” Berman sings in the track’s first chorus, “And the west has made a deal with the sun.”

His affinity for the great outdoors — if not always for the people who occupy it — is on display in American Water more than almost anywhere else in his oeuvre. The notable exception is Actual Air, his only book of poetry, published less than a year after that album. There, he describes the “wind in the tension of the blown trees,” the “enameled moon,” a “Pennsylvania sunset back[ing] down the local mountain,” a “white horse breaking across a white wine-colored clearing,” and “the ideal of Virginia / brochured with goldenrod and loblolly.”

His poems resist easy interpretation, blurring the accessible signifiers in his songs with turns of phrase that upend the meanings of words we thought we knew. “Like Like the the the Death” achieves the same ambiguity by omitting these signifiers altogether.

From left: William Tyler, David Berman, and Cassie Berman. Photo by Pylon Shadow.

From left: William Tyler, David Berman, and Cassie Berman. Photo by Pylon Shadow.

“My life, at home every day / Drinking coke in a kitchen with a dog who doesn’t know his name,” Berman sings in the song’s second verse. It’s one of my favorite lines ever. In “Self-Portrait at 28,” a poem from Actual Air, he imagines his dog having a nightmare about “the part of me that would beat a dog / for no good reason / no reason that a dog could see.” Near the end of that poem, he postulates that the dog can only hold one thought in his mind at a time, “and when he finally hears me call his name… my voice is everything.” The dog in the poem is given substance, if only as a blank canvas for Berman’s neurotic imagination. The dog in the song is a vacant, translucent thing.

The verse’s second half grows bleaker, zooming out once more on a world where “Nobody cares about a dead hooker / Looking like one, standing for many,” where “Life finds a limit at the edge of our bodies” and “A stranger begins wherever I see ’em.”

The indoor, depressive Berman sees humanity in the darker regions of grayscale. The outdoor Berman sees bursts of vivid color in the most microscopic of details. In the song’s final chorus, he makes a rare attempt to bridge the two. “Let’s live where the indoors and the outdoors meet,” he sings.

In his poem “If There Was a Book About This Hallway,” the hallway is “an outdoors that is somehow indoors.” Maybe this song is a hallway — from track eight on American Water to track 10; from the world of the mind to the world of crickets, rabbits, grass, and air; from life to death.

David and Cassie Berman with their dog, Miles. Photo by Brent Stewart.

David and Cassie Berman with their dog, Miles. Photo by Brent Stewart.

There’s hope to be found in the final lines of “Like Like the the the Death”: “Every morning you forgive me, every evening you relive me / And the thing itself is what you give me,” Berman sings, unsure why someone would extend their repeated kindness to him but appreciative nonetheless, “And the morning has cut a deal with the east.” In 1998, and in 2005, Berman still had thousands of mornings left to wake up and struggle with, finding strength and guilt in the forgiveness of his loved ones, surrounded by the air and the crickets.