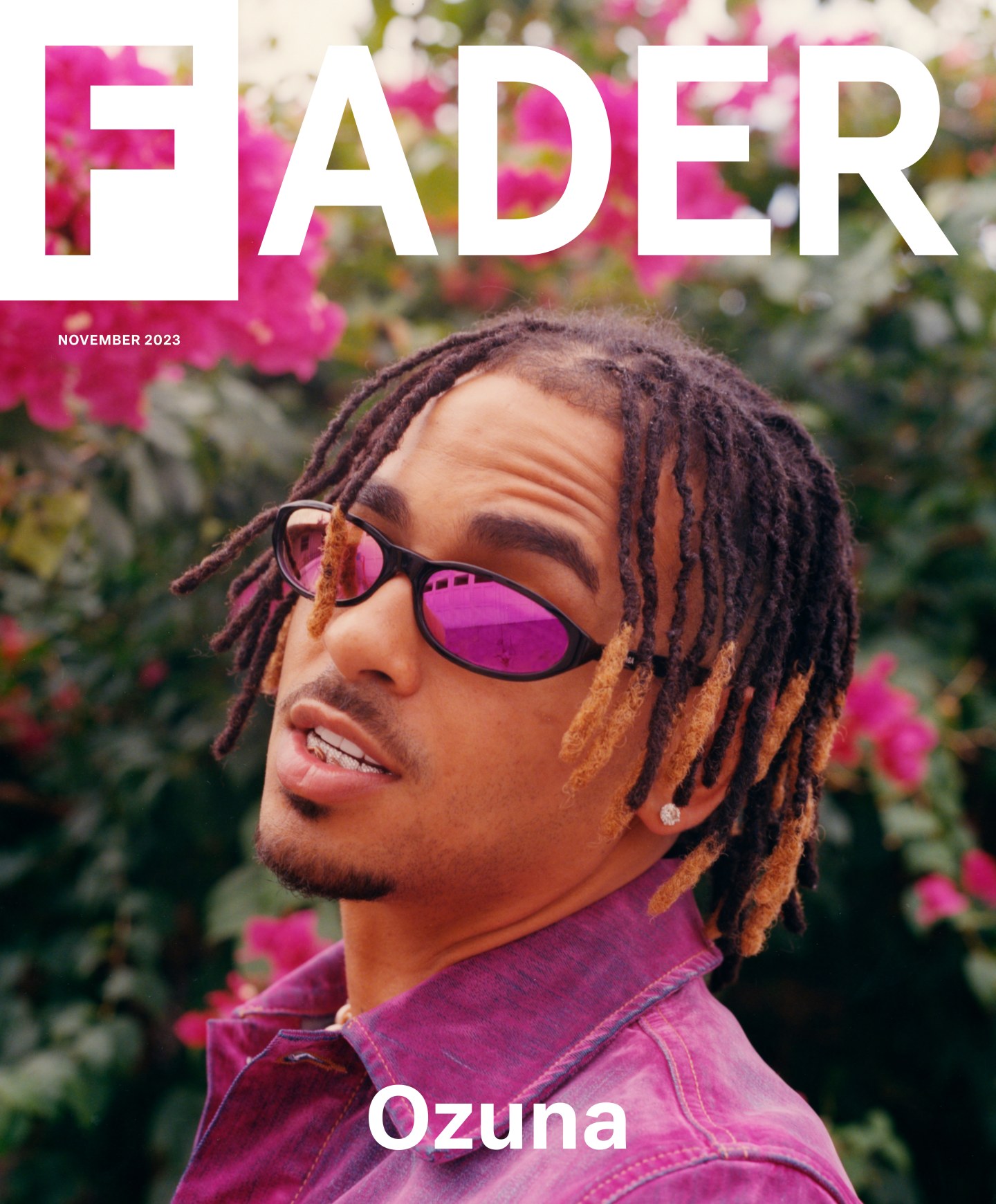

The house is modern, a minimalist brown and white petit palais surrounded by palms — typical of southwest Coconut Grove. I arrive at this enclave of Miami’s wealthiest just before sundown, in a black van with tinted windows. After we park out front next to a green Porsche, I’m led to a sprawling backyard. A small congregation of managers and publicists whispers by the grill, beyond a giant blue pool. Taking all of this in, I’m suddenly in front of the master of the house. He’s dressed low-key — a black baseball cap on backwards, an oversize T-shirt, expensive-looking blue sneakers, and jeans — save for his wrists: a diamond chain bracelet sits on his right, a gold ruby-encrusted Rolex on the left. I say his house is lovely. Ozuna gives me a hug and replies, “This is your house too.”

His placid disposition is a sharp contrast with the odyssey of getting here — at least four changes of time or location, resulting in a chase around Miami. “Everything with [his team] is very on the go haha,” his rep texts me earlier that day. By the time we’re face-to-face, sitting beside the pool, I tell Ozuna that I’m exhausted from trekking around Miami all day. He offers to make me a coffee, and we end up around his massive kitchen island, which is topped with a statue of a teddy bear in a hoodie, one of many three-dimensional models of Ozuna’s logo scattered about the house.

He sings as he pulls espresso shots for the team, that familiar voice — which I’d often heard on Top 40 Latinx radio stations and at mainstream reggaeton clubs — filling the space along with the scent of fresh coffee. I play with his dog, Falco, a large but docile Belgian Malinois. Ozuna takes his espresso with a bit of oat or almond milk. His publicist drinks it black, but he insists she try one of the alternatives, playfully teasing her: “You don’t know if you’ll like it if you don’t try it.”

This would seem to be Ozuna’s approach to music as of late, though it’s certainly not how he operated in the past. He debuted in 2012, breaking through with the club reggaeton track “Si Tu Marido No Te Quiere” and a number of guest features. Early co-signs from pioneering reggaeton duos Zion y Lennox and Wisin y Yandel and appearances on high-charting tracks, such as the inescapable 2018 posse cut “Te Boté,” set the Dominican-Puerto Rican singer up as a eminent force in El Movimiento. Since 2017, he’s released a steady stream of popetón albums that have racked up statues at every major award ceremony, including two Latin Grammys. He has rarely strayed from the chart reggaeton formula of dembow-lite riddims and lyrics about bottles popping, panties dropping, and perreo hidden from an unknowing husband.

Ozuna has become known for his consistency. He’s worked with everyone relevant in El Movimiento’s mainstream, from upstart Manuel Turizo to Spanish pop experimentalist Rosalía, on the tropicore duet “Yo x Ti, Tu x Mi.” Outside of the reggaeton sphere, Ozuna’s collaborations can sometimes feel like copy-pastes from a label seeking to pair him with the moment’s in-demand talent. Global hit “Taki Taki,” with Cardi B and Selena Gomez, and more off-the-cuff collaborations like “Del Mar,” which features Sia and Doja Cat, can feel like the sonic equivalent of that meme where a chocolate bar swims in ramen.

Still, you can’t deny the guy’s voice, a tenor that’s striking on even the most innocuous beats, or his versatility. His oeuvre runs the gamut from tracks like the Akon-assisted afrobeats-lite song “Coméntale” to a number of songs with longtime hero Romeo Santos that meld Ozuna’s radio-friendly reggaeton sound with bachata. He’s further delved into his Dominican roots on a remix of “Baje Con Trenza” with dembow OGs Kiko el Crazy and El Cherry Scom, and as recently as last year on Ozotuchi dembow-dancehall cut “Somos Iguales” with the DR’s firebrand of the moment Tokischa. He even dropped a mambo track with merengue artist Omega in 2021, a year before Bad Bunny made headlines with Un Verano Sin Tí standout "Después de la Playa."

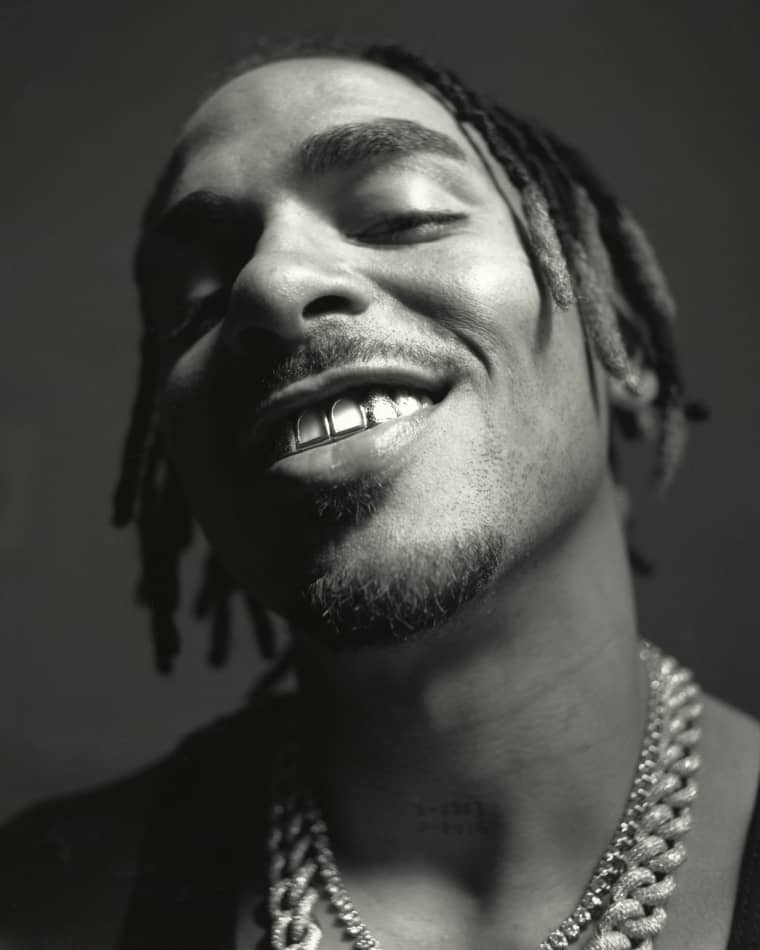

Despite the enormity of his success, Ozuna’s career has largely been projected through the avatar of the teddy bear in the hoodie rather than the man himself. It’s a long-running strategy of reggaeton’s new guard: see Bad Bunny’s deformed rabbit or J Balvin’s use of Takashi Murakami flowers. Working from behind the teddy bear façade has yielded Ozuna a low-key public persona, a swath of relatively safe, formulaic hits, and an inoffensive media presence.

Which is not to say that zone of safety is where he wants to be. Somewhat surprisingly, Ozuna tells me he insisted on doing this interview at his house. “I love doing these more personal interviews,” he says. “It’s always like ‘Oh, come to Univision.’ I’ve done so much of that. It’s like going on autopilot. It’s not that I’m fake, it’s that it’s a job.”

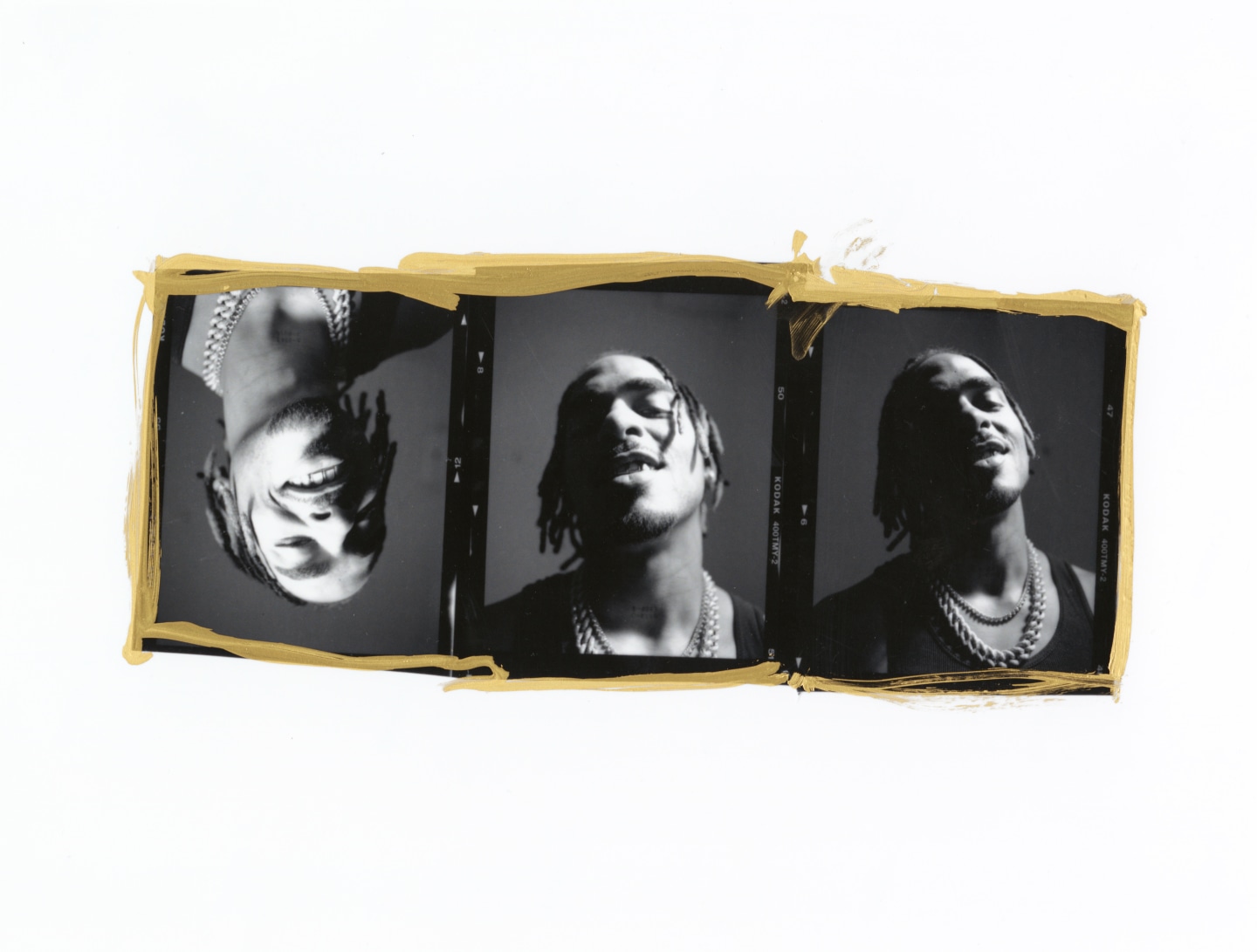

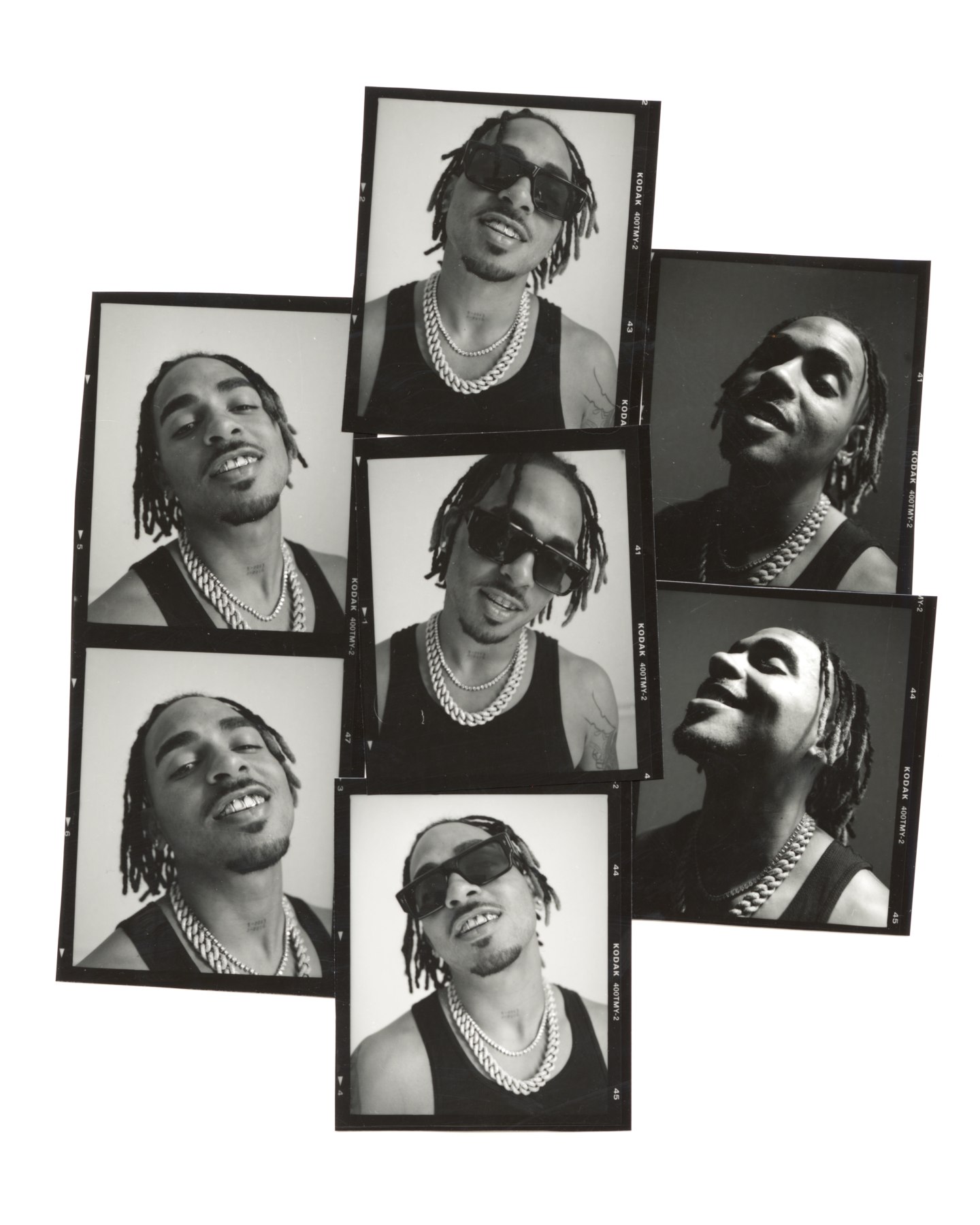

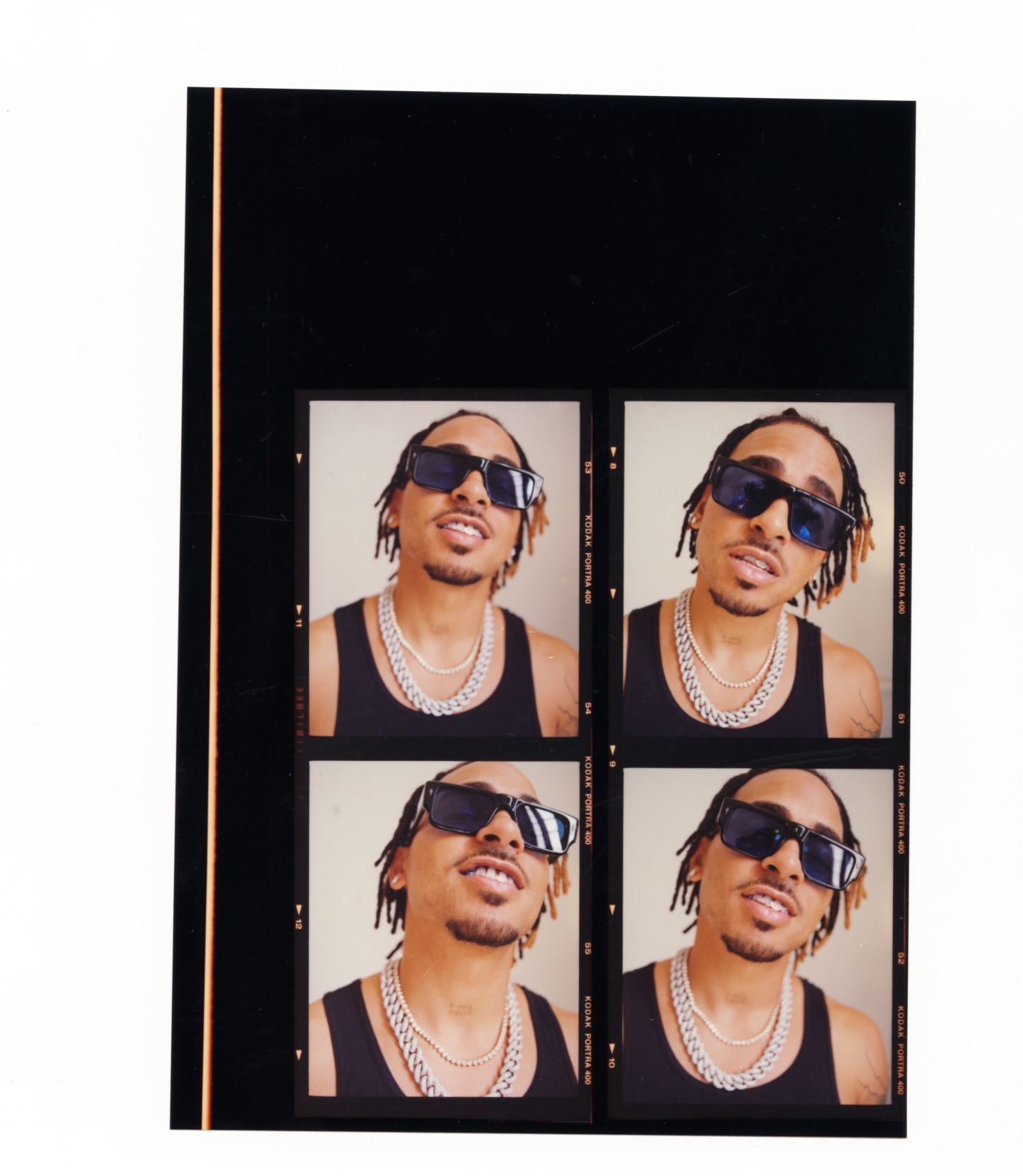

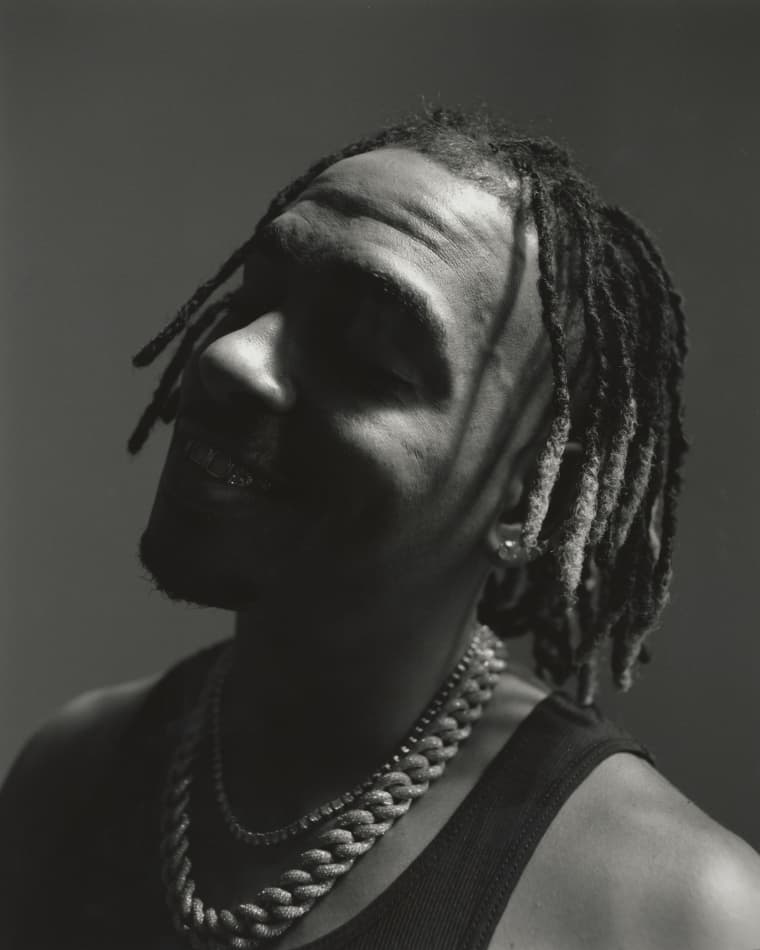

“When you think of a colorful image, you think of youth. When people listen to this album, I want them to take it seriously. We grew up! People want to hear what’s real, what’s clear-cut, in black and white.”

The first time Ozuna himself appeared on an album cover was in 2021, when he released Los Dioses, with Anuel AA. His visage appears again this year on Afro, a lively EP of afrobeats tracks. The choice seems more aesthetic than emotional, though he’s always taken pride in his status as one of the most prominent Afro-Latinx artists on the charts. When he was younger, he stood up to a classmate who chided him by saying, “there’s no Black kid in the Backstreet Boys.” Now, one of his trademark shoutouts is “The Negrito With Light Eyes,” whose acronym, ENOC, gives Ozuna’s fourth album its name. In embracing his Blackness, Ozuna also honors the genre’s roots: the booming dembow beat behind every reggaeton track you’ve ever heard — the “Pounder” riddim created by “Dennis the Menace” Halliburton, itself derived from the “Fish Market” riddim made by Jamaican dancehall progenitors Steely & Clevie — is a Black beat.

“I think a lot of time has passed since the conversation of Afro-Latinidad being a new concept: Me and Gata [reggaeton scholar Katelina Eccleston, of Reggaeton Con La Gata] pushed for the term El Movimiento rather than música urbana because reggaeton, reggae, and Dominican dembow are one singular movement with multiple genres that were embedded with forced migration,” says journalist and reggaeton expert Jennifer Mota, who profiled Ozuna for a 2019 Vibe cover story. “All of these genres have Black influences. They're like sister genres that evolved parallel to each other, and they've always made people dance. The future of music is Dominican dembow and afrobeats.”

It’s not lost on Ozuna that he felt okay to put out an afrobeats album only recently, though he’s dipped a toe in the genre here and there — such as on the Cardi-B assisted Aura standout “La Modelo.” After George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police in 2020, a global racial reckoning in music made waves in El Movimiento, with an emphasis on the genre’s Black roots. “I always liked afrobeats and Jamaican music, I’m a sazón moreno that I don’t even know how to explain,” he says. “In Europe, afrobeats is a whole thing: Davido, Burna Boy, Omah Lay… ‘Eva Longoria’ [his collab with Davido on Afro] hit big in Spain. I dared to try because that’s what was happening in the world.”

The cover of Ozuna’s sixth album Cosmo, out November 17, continues his efforts to show up face-first. The teddy bear is nodded at but is transmuted into a yin-yang logo. In its place, we see Ozuna front and center cradled by a circle of women clad in black. He’s seemingly sprouting tentacles and is wearing a hat topped with bear ears.

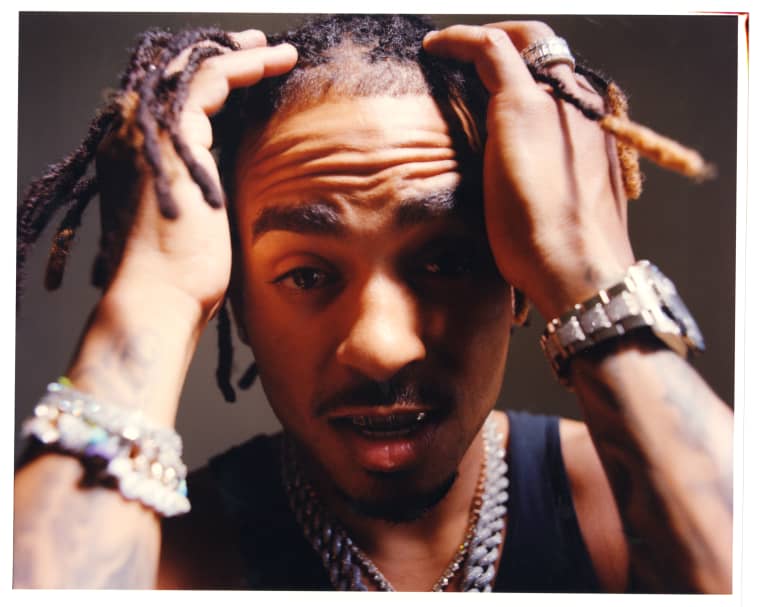

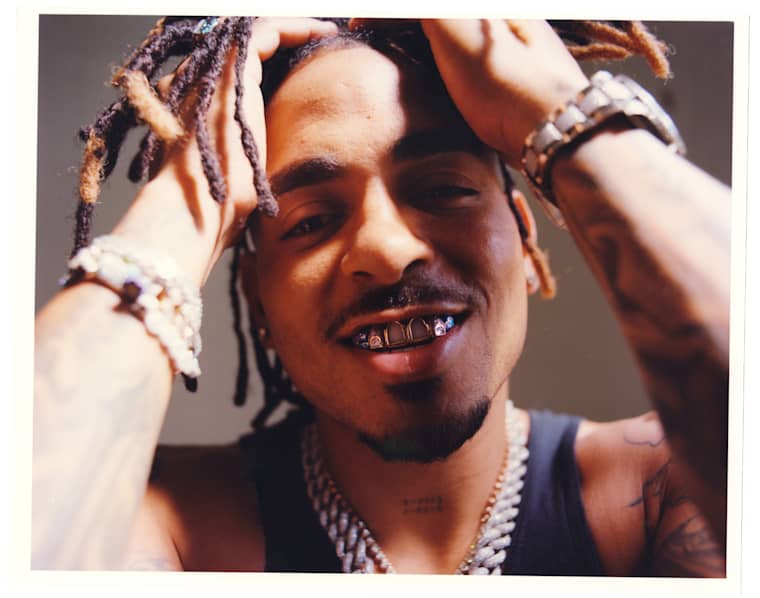

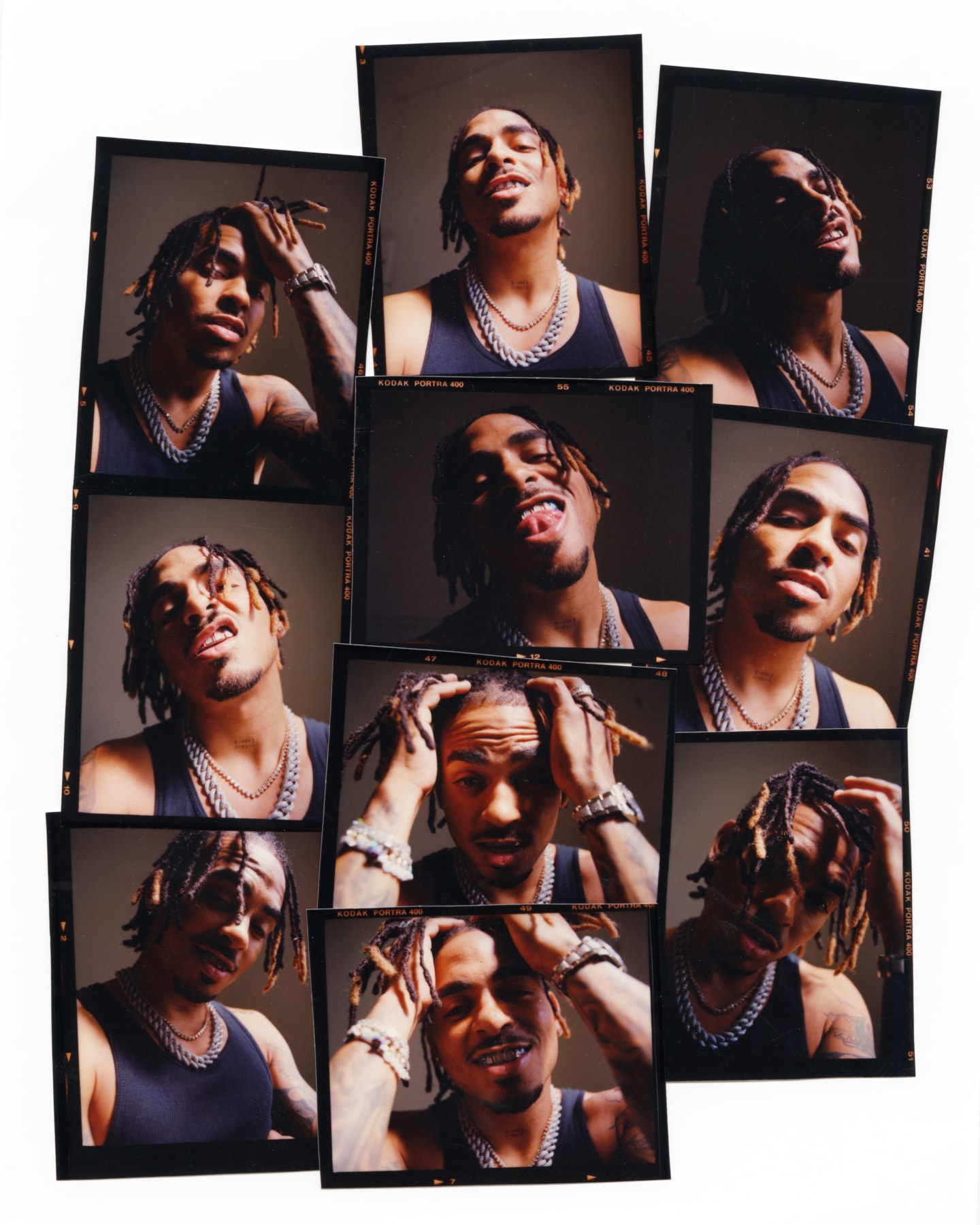

Sonically, it’s clear he’s tapping into the underground: one song, “Clase Azul,” is a booming dembow-driven track that feels far from Ozuna’s usual pop-oriented output. He sings about a heartbroken alt-girl dancing alone at the club who “only listens to Nirvana / With a broken heart no one can fix”. The video sees Ozuna brandishing robotic arm extensions à la Arca and dancing in the middle of a pit surrounded by neck-tattooed, leather-clad extras, imagery more in line with The Matrix or a Rick Owens runway than a multi-colored plush toy in a sweater.

Cosmo is the first time Ozuna has devoted more than a year to an album. The collection boasts several features — including David Guetta on “Vocation”, an EDM track that shares a name with Ozuna’s champagne brand — ranging from Plan B’s Chencho Corleone and Maldy to frequent collaborators Anuel AA and De La Ghetto. He’s sharpened his sound, too: songs like “100 Squats” drip nasty bass straight out of a marquesina; “Baccarat” has an elegant radio-ready swagger destined to make it a club hit. Chencho-assisted initial single “El Plan,” released after the album’s untimely leak, sees Ozuna swaggering about in a black Balenciaga fit. “Fenti”, a more floaty downbeat reggaeton featuring Jhayco (FKA Jhay Cortez) is accompanied by a video where he and Ozuna float in black trench coats amid a tornado of angels, an image that calls to mind Gustave Doré’s illustrations of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy and early 2000s action-horror films like Van Helsing. “These are dryer reggaetons: 'Baccarat' sounds like an old classic track from when Chencho and Maldy [Plan B] or Rasta y Gringo were outside,” he says. “We wanted to bring out that underground vibe. There’s music for the masses, but we’re at a point where people want to hear music that’s real.”

This shift is Ozuna at his most “darks.” It comes as no surprise that he’s going down this route — neoperreo artists like Tomasa Del Real and Ms Nina have been making waves from the underground up, and the mainstream has taken note. Between Cosmo, Karol G’s “Bichota Season” reimagining of her pastel-pink last album, Tokischa’s Halloween single "CANDY," ex-couple Rauwsalía’s undead chic turn in “VAMPIROS” and Bad Bunny’s Nosferatu-referencing “BATICANO” video, it would seem the chart-reggaeton world’s creative directors have been going to the goth rave.

“It was time to leave the bright colors behind,” says Ozuna. “When you think of a colorful image, you think of youth. When people listen to this album, I want them to take it seriously. We grew up! People want to hear what’s real, what’s clear-cut, in black and white.”

That realness extends to Ozuna’s pride in his dual heritage. “ I've spoken to a plethora of producers and artists that were involved in reggaeton's early 2000s globalization. When you think of all the tracks that blew up that were commercial, they were all produced by Dominican producers or composers, using genres like bachata and merengue típico. Many of those artists weren't overly proud of their Dominican identity because at the time Dominicans were discriminated against in Puerto Rico — the majority were Black,” adds Mota. “Dominicans are largely proud of our identity, but those of us born or raised in Puerto Rico didn't have that energy. Ozuna was one of the first to really be proud and embrace both identities.”

Ozuna was set to shoot a video for “Vocation'' in Paris on November 4, followed by a performance at the MTV Europe Music Awards the day after. The awards show was canceled, with MTV saying that as “the devastating events in Israel and Gaza continue to unfold, this does not feel like a moment for a global celebration.” Ozuna performed in Tel Aviv for the second time as recently as this August, and was photographed wrapping himself in the blue and white flag onstage. It’s typical reggaeton-star-on-tour behavior that’s in line with his history as a generally apolitical star. Compared to more outspoken reggaetoneros, especially other Boricuas, he hasn’t been one to speak out against oppressive powers. In an old interview, he was quoted as wondering why the U.S. and Puerto Rico — whose relationship has been cited by many as settler-colonial in nature — couldn’t “unite more.”

An apolitical stance can only serve one so long, though. Ozuna tells me that he’s been thinking a lot about the siege in Gaza, speaking sternly with a pained look. “They’re killing so many people who have nothing to do with any of this. It’s a piece of land that’s not doing anything, and people with a lot of power and money are fighting for nothing,” he says. “What is the President doing in Israel in the middle of this war? It’s unnecessary. When I [performed there, in 2019], it was the first time I had traveled that far with my music. Everyone treated me with a lot of love.

“I think what’s happening is part of a plan to animalize people: not only [Palestinians], but a lot of other people around the world,” he continues. “It used to be that [after 9/11] you’d see an Arab person at an airport or on a plane and feel uncomfortable, and that’s because an image was created of them that wasn’t true.”

“There’s no more exclusivity or professionalism: we’re all on the same boat, riding the same guagua.”

Violence has marked Ozuna’s entire life. His father, a Dominican backup dancer for legendary Boricua rapper Vico C, was shot to death in Puerto Rico when he was three years old. He never met him. Four years ago, he was linked to the tragic shooting of gay trapero Kevin Fret, an investigation that was paused in its early stages but was recently picked back up. Fret had been extorting Ozuna, threatening to release an explicit video filmed when Ozuna was underage, and was killed shortly after. His murder remains unsolved.

Ozuna has acknowledged the extortion and publicly apologized for the video, but the incident has cast a shadow over him that’s been hard to shake. With the rampant — and often fatal — homophobia and transphobia in Puerto Rican society and at large being publicly discussed by contemporaries like Bad Bunny and trans artists on the rise like Villano Antillano, Ozuna’s silence on Fret’s murder has been conspicuous. But when I bring up the murder today, Ozuna begins to get emotional.

“When you know who you are and can’t express it because of your position, it’s worse than being a bad person who doesn’t care what they say or not,” he says. “It was something that affected me, emotionally and financially. I had to rebuild little by little, let myself be known more so people could understand that what happened is not how people have made it out to be. My father was killed in Puerto Rico when he was 19, and that makes me respect Kevin’s death. I stayed on the margins out of that respect for his family, and for what happened. It’s a delicate topic, because you have to respect a family, a mother. My heart is clean, and it has been since day one.”

It seems as if Fret’s death, combined with the ongoing siege in Gaza, has struck Ozuna with a sense of clarity. “We’re all on the same level now,” he says. “There’s no more exclusivity or professionalism: we’re all on the same boat, riding the same guagua. Left or right, Black or white, what we’re dealing with now is people worried about power. We have to support each other.

“I see those videos [of Gaza], and it makes me want to get up and hug my family tighter, love my people more. All of this has done something to us: it’s made us unite and have more patience for each other. I think that [those in power] thought this would cause another reaction in us, but this new generation sees that we all stand at the same level, that we’re here to help each other.”

That desire to change, to move forward, extends to Cosmo. “We need to adapt to what’s happening in El Movimiento right now,” he says. “I think right now the world is in a rebellious moment for clothes and concepts in music and art. I’ve always released music through the teddy bear. That will always be the foundation, but I want people to know who the real Ozuna is.”