Photo by Megan Barnard.

Photo by Megan Barnard.

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, podcaster, and curator of worlds. His ability to find parity in the disparate, along with his exquisite command of the English language, has made him one of the 21st century’s most celebrated cultural critics. Among his works are an alternate history of Black performance in America, a requiem for A Tribe Called Quest, and a series of short prose pieces weaving constellations between pop music, basketball, and the most elemental symptoms of the human condition — not to mention a stunning profile of harsh noise messiah Dreamcrusher for The FADER.

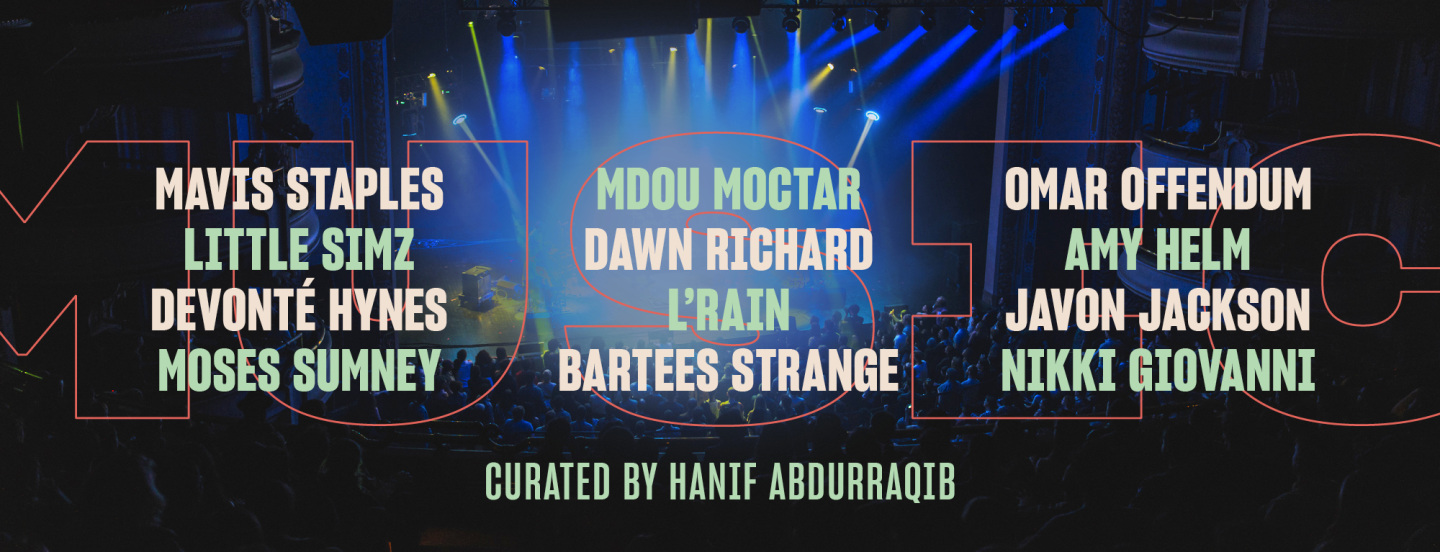

This year, Abdurraqib has taken his talents to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, organizing the institution’s spring concert series. The season started with Bartees Strange opening for Mdou Moctar, a 30th-anniversary screening of the cult classic Juice, and Dawn Richard reprising her 2021 album, Second Line: Electro Revival. Coming up, L’Rain will set the tone for a performance of Moses Sumney’s Blackalachia; Devonté Hynes will play original, never-before-heard classical compositions; Omar Offendum will stage Little Syria; Mavis Staples will sing with Amy Helm; and Little Simz will commune across poetic generations with Nikki Giovanni, whose reading will be accompanied by saxophonist Javon Jackson.

In bringing Black storytellers whose works transcend the boundaries of genre, time, and place to BAM's Howard Gillman Opera House, Abdurraqib is incubating sonic galaxies that he hopes will outgrow the trappings of the historic New York venue. Last week, he sat down with The FADER to discuss the threads between curation, collection, and community building.

The FADER: Where an artist is from informs how they’re considered in the cultural conversation, and this is especially true in hip-hop. It seems to be less of a sticking point, though, for Gen-Z rappers who grew up completely online. Is this an overall positive? Will losing some of the genre’s regional tribalism and local pride (assuming that does slowly happen) bring about some unforeseen negative consequences?

Hanif Abdurraqib: Place and placelessness define my work and my art and a lot of the art I grew up loving. But I also grew up at a time when there was not only a distinct tension and regional push and pull in hip-hop, but distinct sounds. I remember when Outkast came out of Atlanta. I remember hearing Geto Boys and UGK for the first time. And G-funk, all the stuff coming out of the West Coast. These were sounds and aesthetics that defined a place that was not the place I was living. That window to another world, I relied on that. This was, of course, before the internet as we know it now, so I was relying on music to be my portal to an elsewhere, and now I don’t necessarily require that. What’s more and perhaps better is that the internet does afford us a kind of placelessness or a window to an elsewhere that does not require the same kind of sonic and descriptive mapping that music required for me back then. And some of this is also because the music video as a form was like my internet. I was learning about what was happening in places through music videos.

I ask because your program brings together artists from across the world, some of whom reflect more directly on the traditions of where they’re from than others. For your first pairing, you had Bartees Strange, whose music feels untethered to any specific location, opening for Mdou Moctar, who plays in a style that’s very specific to North Africa and the Tuareg people. What made you decide to book them together at the front of your lineup?

Having them open up [the season] felt like an overall manifestation of the goal. Sometimes an entry point is a way of training an audience to understand what they’re going to expect and experience through a process. And Bartees and Mdou were maybe the greatest example I could offer of that kind of training. These are two artists operating at creative, sonic, thematic, boundaries that I think are reaching for each other in some semi-clear ways. And it felt to me that I could make a place where they are in conversation and see what that does to the stage and the people in the room. I wholly believe that live performance is an exchange, a form of conversation, so I needed to find artists who were in some way speaking to each other and asking people to join in on that speaking. When I talk about being carried to an elsewhere, that is also in some ways a rejection of place. I don’t mean to strip these artists of where they’re from — particularly Mdou — or how their sound connects to where they’re from. But to say that you, as a viewer, as an audience member, as someone in the midst of this exchange, get to experience place in a way that you maybe wouldn’t otherwise is to give in to a type of placelessness. Like, “Yes, this is happening in Brooklyn, but the Mdou Moctar set I watched was a portal. I was transformed, taken away.” And so a venue or a city is almost secondary.

It was amazing how loud the opera house got when Mdou moved from the acoustic portion of his set to the electric part. It felt like a switch flipped: people finally got out of their seats and started dancing. How essential is dance to the communal experience of live music?

Oh, yeah, I was desperate for movement. I was pushing for Turnstile, and BAM was like, “Nah, man, their fans would tear that place apart.” And I was like, “But if we’re resetting the precedent for what a space can be, you’ve gotta break a few eggs to make an omelet.” I don’t think Turnstile fans would tear the seats off the place, but movement was so vital to my curation. Who’s going to get people to move, and who’s going to make it so that movement is an afterthought, something you’re required to do? For Bartees, I was side stage, but I went to one of the box seats to watch Mdou because I wanted to look down on the audience and see what was going on. There was a point where he asked people if they wouldn’t mind getting up. And there was a point where that getting up turned into one person moving, and that turned into many people moving. That is what I was after: the kind of artists who would strip away the tentativeness that comes with “I haven’t been out in a while and now I’m doing a thing that is large around a lot of people.” I wanted to get back to the beauty of a communal experience where everyone is experiencing the same thing uniquely.

In [2019 New York Times best seller] Go Ahead in the Rain, you write about the politics of music and dancing and even sweat. Did you look at this curating process from a political framework, or was it purely about booking acts and pairings that would be strong enough to get people out of the house — which, during a pandemic, is political in its own way?

I centered the curation on Black storytellers — Black artists who I believe are operating within the oral tradition in one form or another. And I don't just mean singing words out loud; I mean folks who are using both sound and language to tell cohesive stories, be that in a very tactile sense, like Nikki Giovanni, or by stitching together narratives through a body of music, like Little Simz. But yes, part of this was also a selfish pursuit in which I was simply asking myself, "What would get me out of the house?" I really don't like leaving my house, so the question becomes: What do I want to see? What is compelling enough to take me away from the comforts of my home, which have become immensely comfortable for me?

Let's talk about the 30th anniversary screen of Juice. That movie is so rooted in early-‘90s New York it hurts. But it has so many universal coming-of-age themes too. Do you think a great work of art needs elements of both the local and the global?

No. What I love about Juice is how intensely local it is, because it was outside the realm of my world. The characters themselves were not that far outside of a world I understood. But the actual ecosystem of New York… My parents are from New York, I spent a lot of time there as a kid, and I understood it in a very specific way. It was important for me to understand Juice as a film not necessarily about a place, but defined by its place. So the specificity of place as it presents itself in Juice is vital. It's an important part of the process of that film and the process of the stories told in that film. It’s so deeply tied to a coming-of-age story in New York that New Yorkers — particularly Black New Yorkers — have a really robust affection for it. And I think that really showed itself [at the screening]. Leading up to it, I was like, "Damn, all the tickets sold out for this? It’s just a movie!” But there's certainly more to it than that.

You could sense that during the Q&A, when so many people spoke about growing up in Brownsville or the South Bronx and how well Juice captured that experience.

Normally I get exhausted with the “this is more of a comment than a question” type shit, but that was beautiful. I wish we'd had time to hear more of that. Afterwards I got to revel in it with folks as I was lingering. As someone of a similar era to a lot of the people in the room, it was beautiful to immerse myself in that.

You've got a group of shows coming up in late March/early April: Dawn Richard, Moses Sumney with L’Rain, and Dev Hynes. Then, in May, you've got Omar Offendum, Mavis Staples with Amy Helm, and Little Simz with Nikki Giovanni, all in the space of three days. Other than touring logistics, how did these clusters develop? Beyond the individual pairings, were you going for a larger arc for the season?

I have to give a lot of love and credit to Adam Shore who worked with me on this series and who did so much lifting logistically, because touring schedules and calendars were the hardest part of this. But the big thing for me was: How can I make this a series that defies both genre and generation? How can I find a world where there's some multi-generational conversation happening in the midst of the larger conversation about storytelling? I wanted to get [artists] who could build a world around their work. People have been listening to music and not experiencing it live. But through that listening, they've built these small worlds in which the music lives, and I wanted artists who would bring that to life. I wanted to have moments that felt like they couldn’t happen anywhere else. With the kind of freedom BAM gave me, like, "Here's the opera house, here's a budget, make something happen," you work from the top down. I didn't want to come out timid with this shit. You start with the highest possible dream you have and work backwards from that dreaming. I’m really fortunate that so much of my dreaming could be fulfilled. I love Mavis Staples, and to have [her show] work out was so fulfilling. And to get Little Simz — who I believe is a poet, a novelist — almost in conversation with Nikki Giovanni… How miraculous!

Your “Notes on Pop” and “Notes on Hoops” columns for The Paris Review were at their core beautifully simple pairings: a song with a feeling or memory, or a basketball movie with a certain way of moving through the world. Have you always thought in pairs?

I wish it was just pairs. Sadly, I think in these disparate but infinite stitches of comparison points that, if I'm lucky, become pairs. But they don't begin as pairs, and that's hard for me because I want to tie everything together at once. It’s like, "Gosh, if I've dreamed all of this up, surely I can make it work.” So it takes a real humility in saying, "Okay, you've maybe out-kicked your mental and emotional coverage a little bit." But the good news is you can walk it back a bit. That's always easier for me to do than it is to begin small and try to force my way forward. I find the largest possible place I can begin and jump from there. And on the way down, I'll figure out how the parachute works.

I know you’re a big collector of books, records, and sneakers, and I’m wondering if you see a relationship between that and curating these shows. Do you think of your personal collections as private, or do you feel compelled to share all of them with the world?

Some I keep largely private and some I share because I'm fascinated by the small world they can inhabit. What's wild is I now have people who follow me on Instagram just for the rare times when I’m in my sneaker room messing around. But that doesn't happen often, so they’ve got to sift through all these other weird things: my sometimes political organizing and my sometimes musical rabbit holes. I wish those people the best, and once every three weeks, they get to see me picking through my sneakers. I love sneakers, and I often find myself wanting to build out a world for the curation and collection of the things I'm excited about. But I'm not as eager with the sharing of my bobblehead collection.

Do you have a whole room for that one too?

No, I have a vintage safe filled with them. But yeah, I collect old T-shirts, old music magazines. I love going through and defining the time by the ads going way back to the ‘50s and ‘60s, and just looking at the way some of those things are written. I collect a great many things in my house, so much so that I've begun to feel like I have to slow down. Otherwise I'm making a museum, and I don't really wish to live in a museum.

I was hoping to ask you about that fear of over-collecting. I love to collect things too, but I'm inhibited — not only by my writers' income, but also by the fear that all my stuff will tie me down to a specific place. Do you ever get scared of that?

Not really. I've become more discerning as I've aged, because once you have to move a few times, it's like, "I don't want to carry all this shit." But also because I want to actually enjoy the things I’m building for myself, the things I'm hoarding, and I don't think I can do that if I’m just piling things on top of other things. I get a real pleasure in letting some things go — in saying, "Okay, I’ve gotten all the pleasure I can out of this and I want to fill this space with something else now” — because to me collecting things is about the joy of discovery.

That sounds healthy. Do you think your collection practices can also be applied to building community?

Sometimes I see people who consider community to be just the people who do the things they do, are interested in the things they're interested in. But I think it's really about accountability — people who are willing to hold others accountable through an immense affection, who are tethered to each other in a way where you all lift each other up equally and you all can let each other down. Community is an intentional act of joyful curation. The stakes are significantly higher, to be clear, than whether or not I get a pair of sneakers I've been looking for. But that still feels vital.