In Sidcup, the world feels quiet. Today, British summertime is trying and failing to peek through grey clouds that hang over this verdant south London suburb. Tirzah Mastin, one of Sidcup’s newest residents, is leaning on the window of her local grocery store, ready to give me a tour of the area — though she admits she’ll be learning as we go.

Sidcup is one of those suburbs far enough away from the capital’s centre that you can hear thick symphonies of birdsong, get lost in leafy space, breathe fresh air. As we wander from the high street to a park lined with trees and overgrown grass, Tirzah, a 33-year-old singer and songwriter who releases glassy, experimental pop music under her first name, talks about how much she dislikes phones. She squeals at cute dogs in the distance and shows me a small row of pebbles and stones that locals have painted and lined up on the ground. She’s added one too because, she says, “there’s been nothing else to do.” It starts to rain, the smell of petrichor hanging sweetly in the atmosphere, and she offers me space under her umbrella as we walk to a café.

Tirzah only moved here with her partner and two young children a few months ago, after a furiously busy three years. In that time she released and toured her masterful debut album Devotion; quit her day job as a designer at a print agency to focus on music full time; and gave birth to two children. Amidst it all, she recorded Colourgrade, her alluring, instinctive second album, due out October 1 via Domino.

“Coming from a one-bed flat with no view out the window, no garden, was quite a challenge in lockdown with a newborn and a three-year-old,” Tirzah says. “So we were hankering for space, and then my sister and her family were also moving out here around the same time — if we were gonna choose any peripheral area of London, it’s nice to be near family.”

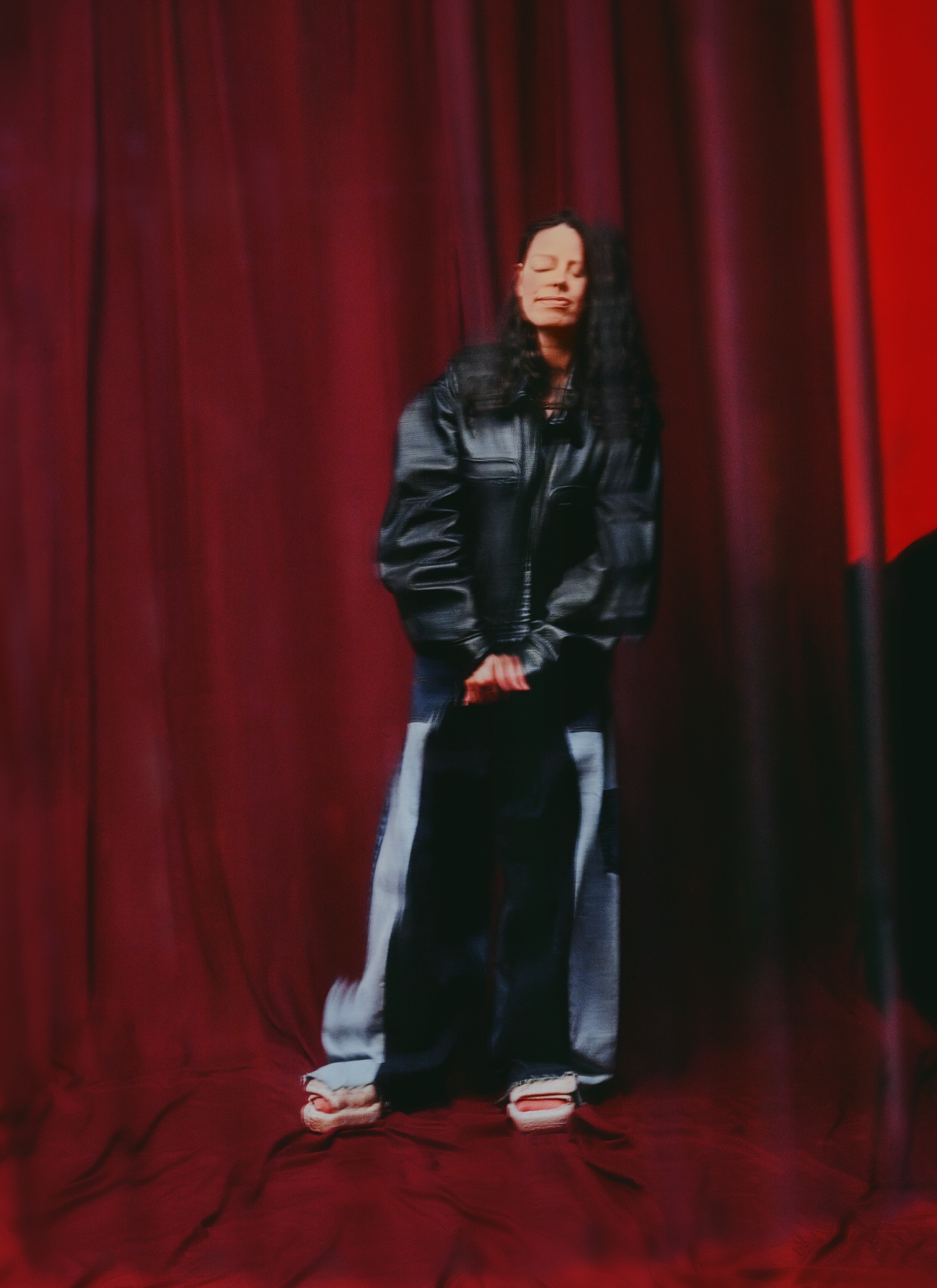

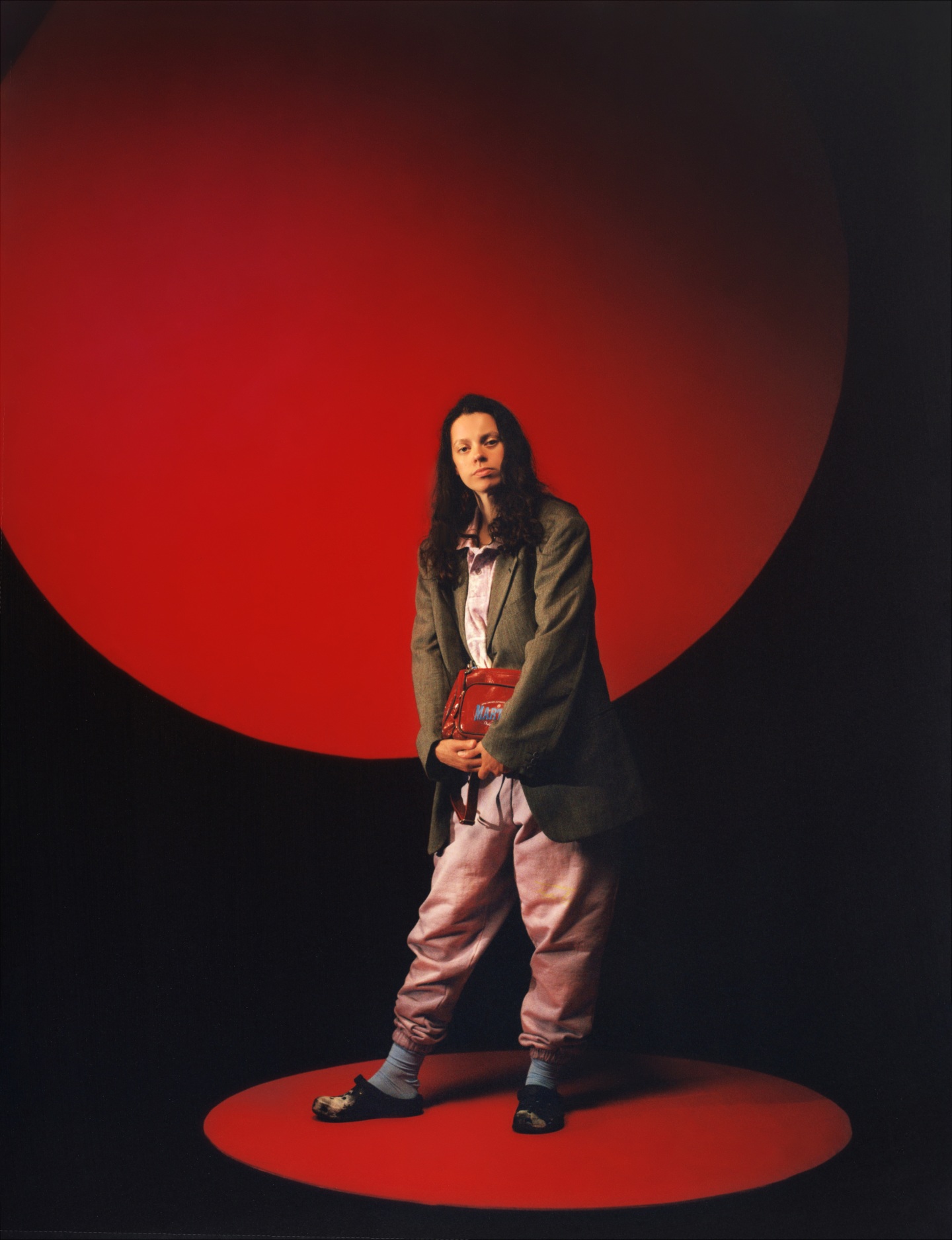

Tirzah is forthcoming, attentive, thoughtful, relaxed. She laughs in warm ripples and is conscious of how frequently she does it: “It’s going to be so annoying for you hearing that over and over when you’re writing this up!” She’s dressed in fuzzy, baggy clothes: a pair of pale blue fleece tracksuit bottoms, a wool plaid shirt, an oversized Carhartt jacket. She has floppy, shoulder-length brown hair and a cozy, well-worn smile.

Tirzah’s manner is in keeping with the easy tenderness of her songs, which can be quiet but are rarely reserved. With her childhood best friend and longtime collaborator Mica Levi, Tirzah has, for the past two decades, been building an edifice of meditative, unorthodox pop tracks, culminating in 2018’s Devotion. A collection of soft-focus love songs, the album proved indelible, its combination of quiet intimacy and disarming, off-kilter electronic production still resonating three years on. Devotion was universally acclaimed, elevating Tirzah to a level of indie stardom uncommon for an artist so unconventional.

Still, she’s the first to play the success of Devotion down: “No one’s ever called me a star before.” Naturally, Tirzah herself sees the past few years not through the lens of newfound fame, but through that of new motherhood. So it’s best not to read too much into her presence in Sidcup, a decision based on practicality rather than any emotional or artistic vision. “I’ve sort of just been getting on with domestic life and work life, really, so I haven’t been paying that much attention to how much we like our surroundings,” she says. “I wouldn’t choose to live here for any other reason than having the space, basically.”

Later in the day we walk along a stream, surrounded by abundant green trees. For me, the calmness brings to mind the concept of forest bathing. Tirzah hasn’t heard of it. A Japanese practice, it’s rooted in the idea that spending some time surrounded by nature can be healing, meditative, even therapeutic. She nods, slowly, as the breeze brushes through the leaves: “I’d believe that.”

In filmmaking, color grading is the process of adding extra body, depth, and emotion to visuals. A camera can’t always capture the true colors the photographer saw; color grading is about adjusting the tones and shifting exposures to get back to the colors that were really seen. For Tirzah, naming the new record Colourgrade was about seeing the work through the framework of color.

“I suppose the way I like to link the songs together is textures and colors,” Tirzah says. “I know in the previous record, we had the sounds Meeks had done labelled as colors — green, purple — and I really loved that. It made sense to me, maybe because everyone learns things in different ways but I really respond to color and pattern and texture. And you can apply colour to loads of things. It doesn’t have to be literally color, you know, it can be moods and emotions. I really like how that could all tie together.”

Devotion comprised songs from a ten-year period of writing with Mica, who is perhaps now best known for their Oscar-nominated work scoring films like Pablo Larraín’s Jackie. Tirzah describes that album as “a collage” of love songs from the era — about her own relationships past and present, but also relationships she had observed around her. There was a striking rawness to the record, lines like “I need all your attention, sometimes I think that’s all I need / But most of all I want your comfort for me” and “I come to you with an open heart, ’cause the last thing I want to do is be apart from you” as clear and fragile as cellophane. But Tirzah balks at the suggestion that her debut was especially personal, laughing and covering her face with her hands when I mention a Guardian review that called the record “frighteningly intimate, lived-in as an unmade bed”.

“To me it doesn’t seem that personal, which I suppose is quite weird,” she says, laughing. “I suppose everyone has that whole palette of feelings and emotions. Sometimes I think we are all the same, with all the same emotions — which, now that I’ve said it, makes me think of that Sesame Street book I read to the bubbas: We’re Different, We’re The Same. I feel like I’ve been listening to love songs for time, really, and it’s all kind of the same to me. And also because it’s me putting myself in other people’s shoes, thinking about other people’s relationships, [Devotion was] not an unnervingly personal thing to me.”

As she pets and coos at another dog passing us by, I suggest that it’s her murmuring vocals, and the heady production around them, that makes what she’s singing feel bare. She laughs again before nodding. “I can see the delivery makes it more personal, but to me I’m just like, ‘People listen to love songs every day.’ I didn’t see any difference at all. But you don’t hear what other people hear, do you? When you’re close to something that you’ve made, you don’t necessarily see the differences over time that other people might.”

Coming into this we were writing completely new stuff, and there was no pressure of matching anything because this is completely new. There was that excitement in starting again.

Tirzah’s music has always seemed to coil and drift like smoke unfurling in dim lamplight. It’s music for late nights: humid afterparties, moments of whispered connection, the touch of skin on skin. On Colourgrade, there’s still that crushing intimacy, but the specifics are different. Although she wouldn’t consider it an intentional theme, listening to the record it’s clear that Tirzah is exploring precious, newfound forms of devotion: love for her offspring, and love for her partner not just as a partner, but as her co-creator in making new life.

Family is important to Tirzah. Aside from music, her life in Sidcup revolves around her partner, Giles Kwakeulati King-Ashong — the musician and producer better known as Kwake Bass, who co-produced and engineered Dean Blunt’s recent BLACK METAL 2 — and their two young children: J, three-and-a-half, and C, 15 months. (Tirzah asks that we don’t use her children’s full names.) She talks a lot about her mum, who is babysitting the kids today, and her siblings, and though she says it wasn’t intentional, the majority of her collaborators across music and visuals are people from her inner circle. That includes Mica, mixer and producer Kwes, visual director Leah Walker, and musician and vocalist Coby Sey, who, alongside Mica, was crucial to Colourgrade’s creation.

Colourgrade was recorded in 2019, after the birth of Tirzah’s firstborn, with the “human deadline,” as Tirzah calls it, of knowing another baby was on the way. It’s an altogether more visceral record than Devotion, with a scuzzy, caustic dissonance occasionally cutting through. (Incidentally, Tirzah mentions that Kwake and Dean were recording in the studio around the same time, and says they unintentionally started “sharing” ideas and sounds.)

Unlike Devotion, these are all new songs, and Tirzah revels at the freshness of it. “Devotion was pulling together ten years of work, whereas Colourgrade was kind of more actively written,” she says. “In some senses making Devotion was more a process of editing and curating, and we had so much material we drew a line under. So coming into this we were writing completely new stuff, and there was no pressure of matching anything because this is completely new. There was that excitement in starting again. And we’re different people from ten years ago, so it’s gonna be different.”

The other big difference was that Coby had joined Mica and Tirzah in the studio to work on this album as a whole — a change from Devotion, where his work featured on specific tracks. The trio bonded while touring Devotion together, playing shows on the weekends so that Tirzah could devote her weeks to taking care of J. “We’d been playing lots of shows, and [I was] enjoying where the playing went, really. To have those memories of travelling together, it was very special. And in terms of writing Colourgrade, we had that experience to draw from,” she says. The way she, Mica, and Coby made Colourgrade, then, is both a natural progression and something of an overhaul. “Those roots are in place from before […] Everything kind of solidified, from when Devotion was forming as a live thing, to now feeling like we’re one kind of breathing organism.”

For Mica, the album is the direct result of that live relationship the trio had formed. “Playing together live bonded us together, and it felt like the natural thing to do, to try and capture what we’d got going as a band into material for the next thing that happened,” they say over the phone.

This is the crux of Colourgrade, on a sonic level at least. “It’s not as manicured as Devotion,” Mica continues. “The roughness, the accurate recording, the time it takes to get places, it’s a bit of a statement on how things feel live. Maybe it’s a reflection of the age that we’re at as well, we’re taking our time but we’re not trying to make everything neat and fit. It’s sort of unpolished. I’ve left it as alone as much as possible, basically, like a warts-and-all attitude towards it. But I hope it doesn’t mean it’s not generous and that we haven’t bothered. It’s just trying to be as truthful with our arrangement of three as possible.”

As a result, there’s a jarring heft amid Colourgrade’s beauty. Sometimes guitar slashes through the gentle atmosphere like serrated metal; synths drone with elemental vibrational force. Squelching closer “Hips” finds Tirzah almost in prayer atop frantically juddering synths; “Crepuscular Rays” sounds like it’s being beamed in through a tin-can telephone, all smudged guitar and wordless, woozy vocal lines. It was these songs — the former with its visceral electronic edge, the latter drifting, dreamlike — that dictated how the trio wanted the album to sound. “It felt like there were two worlds to Colourgrade, really, and so it was about how we’d merge them together,” Tirzah says. “One was a lot more guitar loops, that sort of acoustic world, then the other world is sort of more bass-heavy, more electronic.”

There are songs here about figuring out your role as a parent, about labor, even a soothing post-lullaby, where Tirzah mumbles: “My baby, ooh she’s sleeping tonight.” The track was recorded at night, Tirzah explains, back when she lived across the road from the studio, and could slip there to meet Mica after J had finally fallen asleep. In general, the album was created around the busy schedules of the trio — not least with Tirzah having a newborn child. “All of these things come into it,” says Mica, “The moods, the environment, the weather, all of that stuff has an impact [on how it sounds], especially when you’re leaving all that sort of thing in.”

Despite being initially cagey when I ask if Colourgrade speaks directly to her experiences of motherhood, Tirzah eventually concedes that, in some ways, it does. The artwork is a close-up of her torso, hands poring through what appears to be a colourful picture book. “One of the things I wanted to get across was the comedic value of new motherhood,” she says. “That whole spiritual side to becoming a parent is so huge, but there’s also such comedy and mundanity in what your life becomes — it’s literally just laundry and bums. And that all comes with the joy of it, because it’s so funny and nuts, but you know you’ll look back and think of those endless days of washing clothes and bottles.”

Family is threaded into Colourgrade in the way that romantic love was on Devotion. “I’ve got these new loves in my life that are in my thoughts all the time,” she says. Still, she’s resolute about not wanting to go too deep on the intimacies and intricacies of love for a child vs love for a partner. “I feel like I would have to write a book about that,” she eventually deflects with a laugh, replying via voice note after thinking about it for the day. “I think my answer is constantly evolving. And it’s almost too personal to answer I think. I feel like I’ve put it in the words, in the music, so I don’t want to talk about it.”

Tirzah stresses repeatedly that what comes through on Colourgrade is about her own experiences and feelings, that this is not some kind of definitive statement on being a new parent. For her, any subject matter you might pick out as a listener is just a by-product of the way she creates.

“The generosity of music is that you can take it as you want,” she says, “Talking about personal things with the album, it doesn’t really feel relevant in some ways. Even though it is an album about [parenthood], when questions come up about it, not only is it a personal thing, but it also feels like the control has been taken out of my hands a bit, because it wasn’t intentional.” Over the two weeks in which our conversations take place, Tirzah meanders over this point, aware of what the songs have come to mean but also guarded about that concept. She consistently sidesteps anything that feels too personal, partly because of a desire for privacy, but also because she doesn’t want the songs weighed in specifics. “Realizations about meanings of songs have come to me, like, a year or so later after the songs were written, so then to hammer home on motherhood too much feels not accurate.”

Tirzah is more concerned with the emotional atmosphere of her records, and she’s conscious of not wanting her own life experiences to bleed through too much.

“You don’t want to ram it down someone’s throat, I s’pose. We record it there and then, so either you scrap it or you stick with it in the hope that it’s not doing that — that you’re inviting someone in, inviting them along, as opposed to laying it out too much for them,” she says. “When I think about writing with emotion, I’m thinking of the end result as opposed to just writing a song that’s gonna make someone feel sad.” She laughs. “That might just happen, but it’s not my intention.”

This idea is embodied in the recent video for “Sink In,” Colourgrade’s second single. There an embracing pair of dancers contort and sway, a dance that Tirzah tells me is a mixture of tango and sports acrobatics. “We thought it could be really fun and exciting to have dancers doing a classic, old dance mixed in with something contemporary. [Director Leah Walker] took that idea and applied everything else. I love what she’s done with it.”

The visual is dark and thrilling, the dancers dressed in muted tones, gliding and splashing through water. There’s a tactile electricity between them as they spin around, as though they’re in some kind of wind-up music box. Their movement mirrors the intense grace and physicality of the music: synths and drums echo all around while Tirzah sings: “I am sinking for that feeling.” The lens eventually pans away and we see the pair still dancing in the distance, as if they’re endlessly together out there on some other plane. Like all of Tirzah’s work, it’s not about specifics: it captures a moment, immortalises a feeling, canonizes the sparks of human connection.

The youngest of five children, Tirzah grew up in the sleepy Essex town of Braintree, 40 miles or so north-east of London. She has always been close with her mother, who worked in jewelry repair. It was she who gave Tirzah some of her formative music experiences on drives to London to meet clients, playing compilation CDs on the way. “I’m pretty sure one of them was called Woman II Woman, or something like that, then there were those ones you used to get for free in newspapers,” Tirzah recalls. Tirzah shared a room with her sister back then, but whenever she had the room to herself, she’d make the most of the privacy, pressing play on her CD player and singing along.

“I liked ballads,” she says, listing off her favourites, “Tina Turner, Whitney Houston, Barry White—”

Was she singing along to Barry White as a small child?

“Probably!” she scoffs. “Giving it my best baritone impression. And I remember always looking forward to Al Green coming up on the compilation.”

Pretty much all the artists Tirzah mentions are greats in the pantheon of love songs, though she’s hesitant to suggest that it was this particular subject matter that was especially calling to her. “I don’t know, I guess it must have seeped in in some way,” she offers. “It’s easier looking back, isn’t it, and putting meaning on it? Rather than knowing as a child what you thought.”

She talks instead about being drawn to sounds and feelings: “I really enjoy the melodic line of delivery. I realise everyone tunes into different things when they listen to music, and I have friends who get deep into the undertones, and they’ll be thinking about way more things than I am. But first and foremost I enjoyed singing, there was no technical or intellectual thing behind it. It’s just the enjoyment of it.”

When she was seven years old, Tirzah’s mother took her to a classical concert at school. While the details of the evening are hazy in her mind now — “Maybe it was a duet? A trio?” — she does remember that it was at this show that she saw someone playing harp for the first time, and her mum asked if she wanted to learn how to play. “I don’t think I had any big reaction to it,” Tirzah says, “But maybe she could see I was interested. I think it was more that my mum’s always been musical but had never learned an instrument. She always loved singing. And so I suppose she naturally encouraged that in all of us siblings.” Tirzah started learning on a Celtic harp, on loan from a local music trust. After learning under various teachers, it was suggested she audition for music school, and so it was, aged 13, she ended up at the Purcell School for Young Musicians in Hertfordshire, the oldest specialist music school for children in the UK.

It was an exciting time, she says, recounting her first day visiting as feeling “like summer camp,” complete with dorm rooms. After two girls in her old room left, Tirzah found herself moved into a new one, with three new roommates. One of them had started playing and writing music from the age of four, and had been at the school since the age of nine. That was Mica.

The connection was instant. “Meeks was listening to the Beatles at the time — ‘Maxwell’s [Silver] Hammer’ definitely comes to mind as one of the songs they were playing a lot,” she says, explaining how she’d swap CDs with people in different classes, learning about sounds from around the world.

For all the music she was discovering at school, though, Tirzah was finding herself less and less interested in the harp, falling out of love with classical music. “I hated the lessons with a passion for quite a while, which is why I separated away from it a bit. But later on in life discovering Dorothy Ashby, Alice Coltrane?!” She groans. “Where was I?! What? Why? I could still be doing it now, I think, if I’d not had that unenjoyable experience and had been able to embrace those more alternative ways of playing.”

Every few years Tirzah plays harp again, for fun, but she’s mindful that keeping the instrument at home might be a little hazardous with two small children. I ask if she thinks any elements of her classical training and music school play into what she does now. “There probably are roots, without me knowing,” she says before backtracking. “But maybe there aren’t. I would say not, because I’ve never been that technical. I’m sure being in music school is definitely going to have impacted what I do, somehow, no doubt, but I remember having a handful of singing lessons at school, and they were very classical-based too, and I didn’t really connect with them either. I’ve never been a technical singer. I certainly appreciate it, but it’s just not something I delve into or think about.”

The singing she did enjoy doing was with Mica, who was always playing guitar — a perfect accompaniment. “It started out just like, joke songs, silly songs that we made up,” she says, “But then one time Meeks said we should actually write songs.”

Mica was taking a music tech class, and so the pair of them started using the room for fun — but that was all Tirzah saw it as back then, whose focus remained the harp. “I was never thinking like ‘Oh, this is my partner’ — but probably without realizing I was liking [singing with Mica] a lot more than a lot of other stuff I was doing there.”

They carried on writing music together through their school years, Mica crafting the beats and Tirzah singing. “I never thought to write the music, it wasn’t something I was into. Even years after sitting by Meeks doing it on the computer, I have no idea about Logic or anything, which is quite shocking actually,” she laughs. “Surely I should have been paying some attention.”

The future that Tirzah imagined for herself as a harpist, in chamber orchestras or as a session musician, didn’t especially appeal. At the same time, she had found herself spending a lot of time in the school’s art room with a “lovely art teacher,” and decided to apply for a foundation course studying art, textiles and fashion, before studying textiles and design at university. Her day job in the years thereafter was as a print designer in the fashion industry.

For Tirzah, there had never been any fixed plans about what the future might look like — rather, it was all intuitive, or “going through the motions” as she puts it. There was no external pressure to choose a certain path based on what she was studying, and so she just followed her gut feeling of what was bringing her joy.

Of course, the music didn’t stop, not least because Mica continued studying composition, and was becoming a known entity. The pair’s collaborative process was never particularly regimented, Tirzah says. “We were just mates doing what mates do, there was no seriousness of ‘future’ I thought about with that.” Over the years, they remained inseparable, making songs together whenever they could. Parting ways after school “didn’t feel like a transition, other than us being in different places on a laptop, instead of being in school together. I’d go visit [Mica] wherever they were staying, and we would just be making some music, because that’s what we always did.”

By 2012, Mica had become a darling of the UK’s DIY pop scene, as both a DJ and as the auteur their band, Micachu and the Shapes, now called Good Sad Happy Bad. One day, Tirzah and Mica were hanging out in the hours before one of Mica’s DJ sets. “They said ‘Let’s just do a last minute track for fun, just to pass the time, [and] maybe I’ll play it later.’”, Tirzah recalls.

The DJ set was Mica’s 2012 Boiler Room set, and the song became “I’m Not Dancing,” Tirzah’s first look-in as a genuine alt-pop star. The song went down so well in the set that, within a few days, someone from Greco-Roman, the influential leftfield pop label co-founded by Hot Chip’s Joe Goddard, got in touch, wanting to put it out.

Mica feels central to Tirzah’s story in so many ways. Their partnership has only been refined with each release — following the I’m Not Dancing EP, there was the dreamlike experimental pop of 2014’s No Romance EP, then a mixtape, What’s the Time, in the same year. The pair’s 2015 single “Make It Up” has become one of Tirzah’s calling cards. In Mica’s early, standout Boiler Room sets, you can find Tirzah singing idiosyncratic live vocals over Mica’s whirring beats, the pair grinning throughout.

Notably, it was through Mica that Tirzah first met both Giles and Coby. The latter friendship formed in much the same way as Tirzah’s relationship with Mica: hanging out, going dancing at classic London club nights like Plastic People, and jamming in the studio. At the start of 2017, Coby joined the pair for some of the Devotion sessions and, later, its accompanying tour. The strong connection they forged there has carried through to Tirzah’s second album.

In the studio, the trio will generally jam for an hour or so, Tirzah reacting to the beats and Coby’s vocal lines in the moment, crafting lyrics and melodies that capture how the music makes her feel as well as how she’s feeling at that time. It’s a kind of musical abstract expressionism, led by the immediacy of mood and reaction, rather than rigorous planning.

“When I hear the songs back, they all kind of feel like diary entries,” Tirzah says. “Diaries of times that we spent together, of moments that we captured together — either Meeks and I, or Mica, me, and Coby.”

Coming from my days which are filled with tasks on a necessity basis — bums, breakfast, clothes — as a daily activity, where is the space for creativity? When I’m in the thick of what needs to be done today, I need space to be able to create, and for that quite often you need money and time

Mica agrees. “I find it kind of hard to listen to — maybe because it’s like looking at a photograph. And if you’re too close to it, like it’s only a few years ago, it’s kind of hard to handle, but when it’s from longer ago you can say, ‘Okay, that was then’. I’m lucky to have that kind of marker, but it’s quite a public display.” They laugh before continuing: “The recording process is a case of taking 24 pictures, and one of them’s, like, really beautiful, as opposed to taking one of them and really scrutinising it and trying to put too much conscious influence and human heaviness on it. To just let it be a bit.”

“Something that I’ve taken from [working with Tirzah and Mica] is reaffirming the importance of intuition in music-making,” Coby tells me over Zoom. In a marker of their closeness, he refers to Tirzah as his “sister-friend.” “It’s made in a way where we’re going by feeling, rather than method. Despite the fact that, of course, with the instruments they studied at school, both Tirzah and Mica are classically trained — I’m not sure whether that’s influenced how they make music, maybe it has, but I get the impression that it’s not a conscious thing. Instead it’s an affirmation of trusting and instinct, and going with feeling. I can’t emphasise that enough, and the kinship I have with those two, as well as the other people within our sort of musical family.”

Later, in a group call with Coby and Tirzah, Mica agrees. “I’m not thinking that consciously when we’re creating together,” they say. “Because of all the time we’ve spent together, we just hang out and play. It’s a case of looking at what comes out of the jam, and seeing if there’s anything Taz could write to, out of that.”

“The sessions were mainly ensuring we had time together and enjoying it,” Coby adds. “In many ways, when we’re jamming it feels like we’re talking anyway.”

Tirzah agrees. “It’s like a dialogue. I feel unbelievably lucky that I can do something like this with close friends. I can’t really thank serendipity enough… or Mica and Coby enough.”

There’s an energy that radiates between them, comfortable silences, nudges of “What would you say Meeks?” or “Would you all agree with that?” Ultimately, Tirzah sees Colourgrade not as her solo record, but as a representation of what the three of them make together.

“The way I hear it, the focus is on us — that’s how I think of it, as a project, rather than the melody that sits on top. To me, it’s the whole package, it feels like a group project. Which I suppose is something that people might not see or hear,” she says. “[Coby and Mica will] be jamming for ages before I dip into something, and the words as well, they come off the back of humming and subtlety and murmurs of words, and then after that it’s how we all feel about it. It’s a concoction, not just the vocalist and the track.”

True to this, the songs that comprise Colourgrade are love songs that look beyond romance, burrowing into love as family, love as friendship, love as connection, as much as they may speak of Tirzah’s own life. And they are just as much love songs forged from new family as they are from the creative family she’s made with Mica and Coby. “Hive Mind,” one of Colourgrade’s highlights, encapsulates their kinship. It’s an almost-nursery rhyme, with Tirzah and Coby’s hushed voices engaging in a back and forth that; over the course of the track, practically melds together. It brims with the intimation that some things are unspoken but understood.

Back in Sidcup, the sun has finally arrived. Tirzah radiates contentment, even as she, somewhat uncharacteristically, checks her phone — solely, of course, to make sure the kids are doing okay. We both order jacket potatoes topped with beans and cheese, salad and coleslaw on the side. She delights at the reminder of a simple British school lunch staple.

Through mouthfuls of food and over the sound of cutlery on plates, locals stopping by for tea and cake and sandwiches, we talk in tangents — whether you could teach empathy to AI, how people wrongly conflate shyness with aloofness, spirituality.

“I believe in ancestors, energies, all those things to be honest,” she says, “I think it’s all up for grabs, and me personally, I just think you can’t shut your doors to anything. I’m not a religious person, I was raised on the dregs of that kind of belief. But throughout my life I’ve never had it put upon me, or looked for it — I mean, we’re always looking for answers all the time.”

It’s often assumed that domesticity and the security of family life stifle creativity, and can stunt the time available to spend on our friendships, too. Tirzah acknowledges that this can sometimes be the case: “Coming from my days which are filled with tasks on a necessity basis — bums, breakfast, clothes — as a daily activity, where is the space for creativity? When I’m in the thick of what needs to be done today, I need space to be able to create, and for that quite often you need money and time. So I can fully appreciate [that] creativity is not accessible to everyone.”

And yet Colourgrade comprises Tirzah’s most daring and exciting work to date. Partly, this seems down to a distinct openness to possibility. “It would be boring to start any creative endeavour with boundaries,” she says, “You want to be open to everything. Why not? Everything’s up for grabs, everyone has a right to be creative.”

Later, we’ll head back to the grocery store — Tirzah has remembered they’ve run out of ginger at home. The quick switch, from Tirzah the electronic star to Tirzah the mother and partner, is seamless. In Sidcup, the world feels quiet. All the better for Tirzah’s world to get brighter, weirder, and louder.

Credits

DP: Ivor Alice

Photography assistants: Lynn Hayleigh & Ivor Alice

Styling assistant: Charlie Benjamin

Set Design: Y Lan

Project manager: Daniel Falodun