Courtesy the artist.

Courtesy the artist.

For Sadie Barnette, glitter is subversive and political. In her most recent work, the Oakland-raised artist uses neon particles in all their gleaming and “girly” abstraction to, as she says, “reclaim power, flip it, and re-appropriate it.” Featured in the exhibition All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50, currently on view at the Oakland Museum of California, Barnette commemorates the legacy of the revolutionary nationalist organization on the fiftieth anniversary of its landmark establishment.

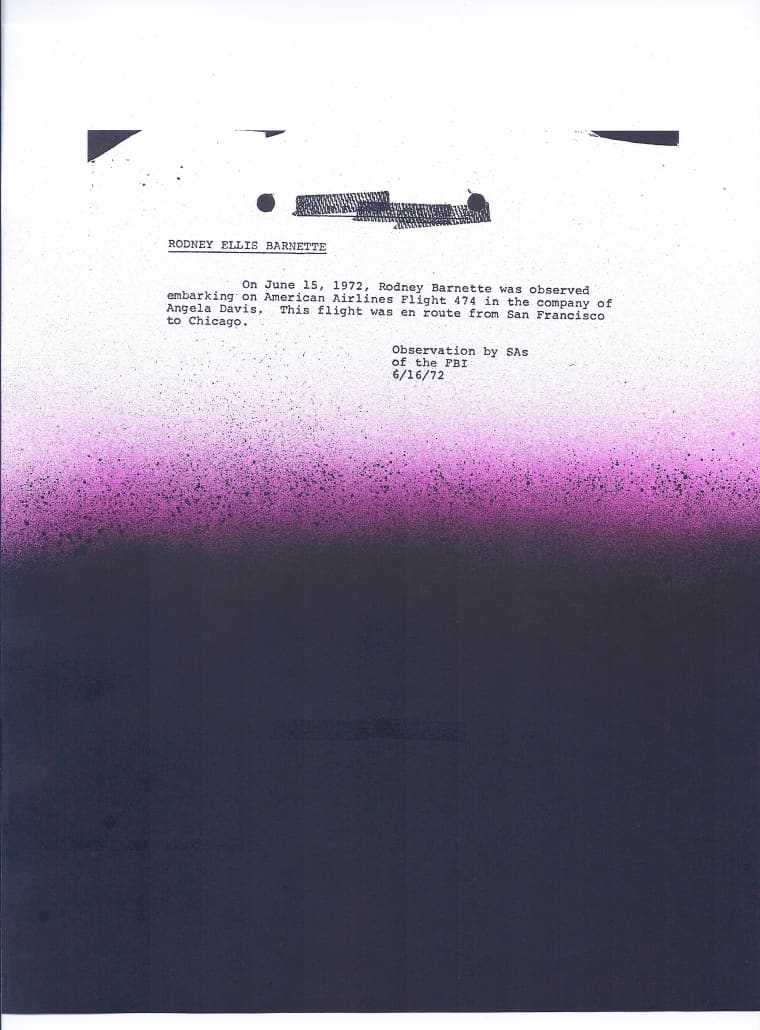

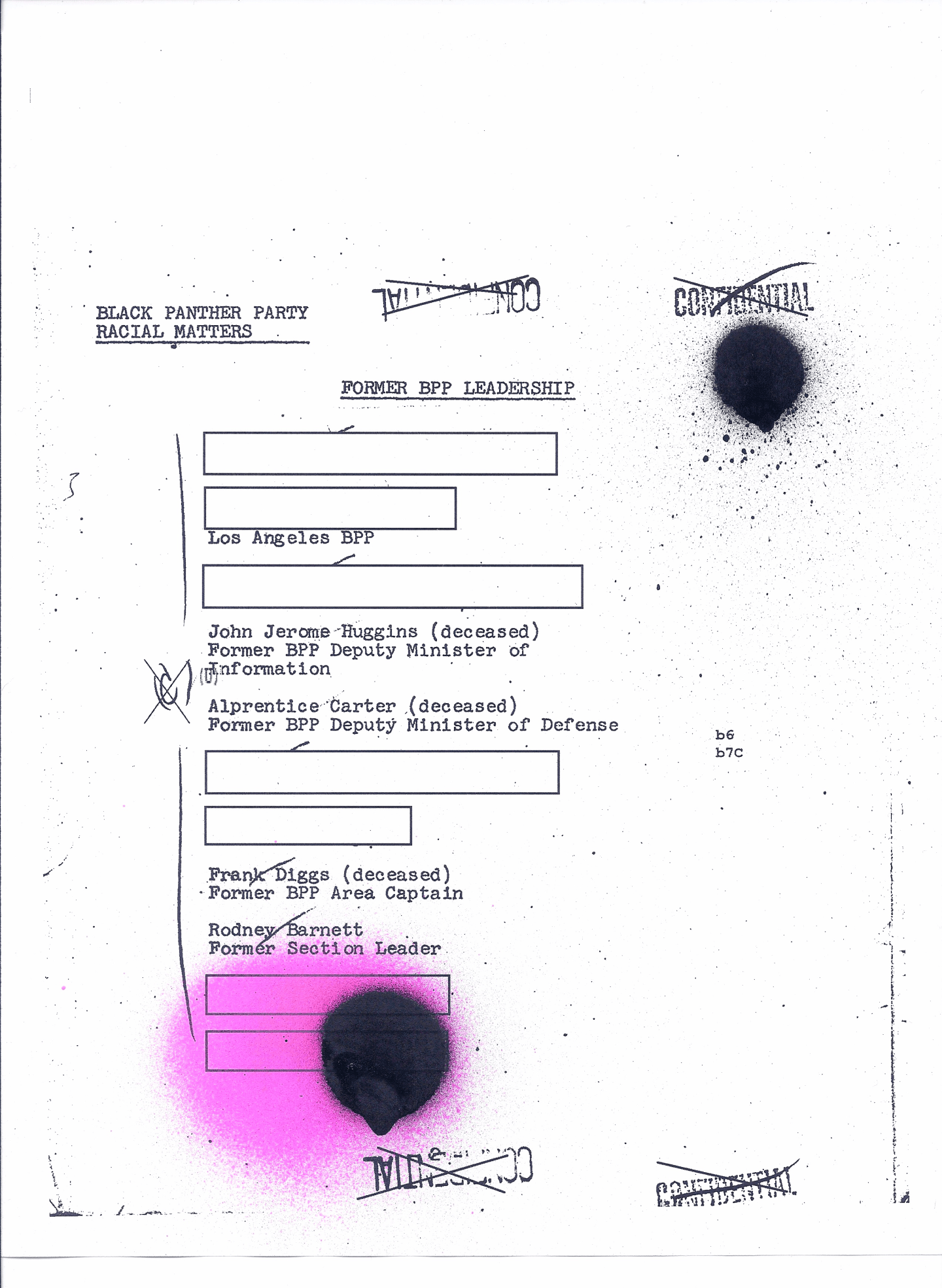

Barnette is the daughter of Black Panther Party member Rodney Barnette, who co-founded the Compton, California chapter in the late '60s after serving in the Vietnam War. (At one point, he lived with Angela Davis while she was on trial for murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy charges in 1972.) For the show, the 32-year old artist obtained her father’s FBI files — a whopping 500 pages — to better frame the arc of her family's story.

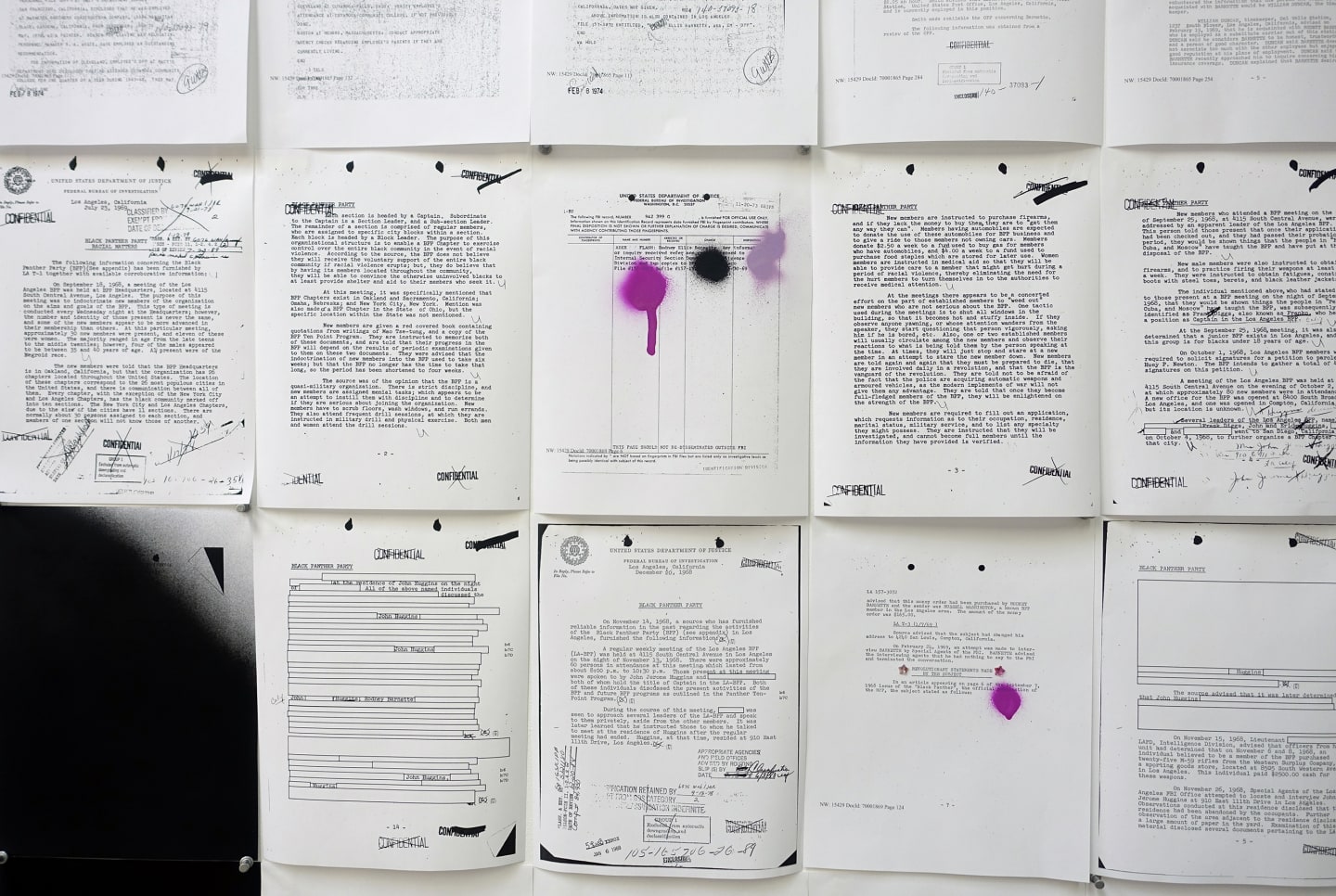

A wall covered in pink glitter. In its center, a black man’s mugshot is etched in pencil and is surrounded by Rodney Barnette’s FBI records, each one reimagined in splotchy black spray paint. Elsewhere, there are photos of family members and friends from Oakland and Compton. Taken in full, Barnette says that the installation was her way of taking control of her father’s narrative from the government.

A former artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Barnette is now based in Los Angeles. She recently spoke with The FADER about rooting her practice in photography and mixed media, and connecting notions of family to the political.

How early were you aware of your dad’s activism and his founding of the Compton chapter of the Black Panthers? Was it something you talked about as a family or did you experience it more fully as you got older?

Both of my parents were very political and we spoke freely about activism and politics growing up. My parents met working in a liquor bottling factory; they became involved with union issues and organizing early on as part of the Labor movement. My dad was a labor organizer and my mom was a labor commissioner for the state of California. This was the early 1980s. But my dad being in the Panthers was more like family lore.

So this golden anniversary of the Panthers brings about lots of family memory, some seemingly quite painful?

Recently my dad has spoken more openly about the Panthers and being in Vietnam. And I understand, it’s hard to talk about. Lives were lost, friendships lost, paranoia set in about who was an informant. So for a long time he didn’t speak about it. When he came back from Vietnam, police were doing search and destroy missions just like in Vietnam.

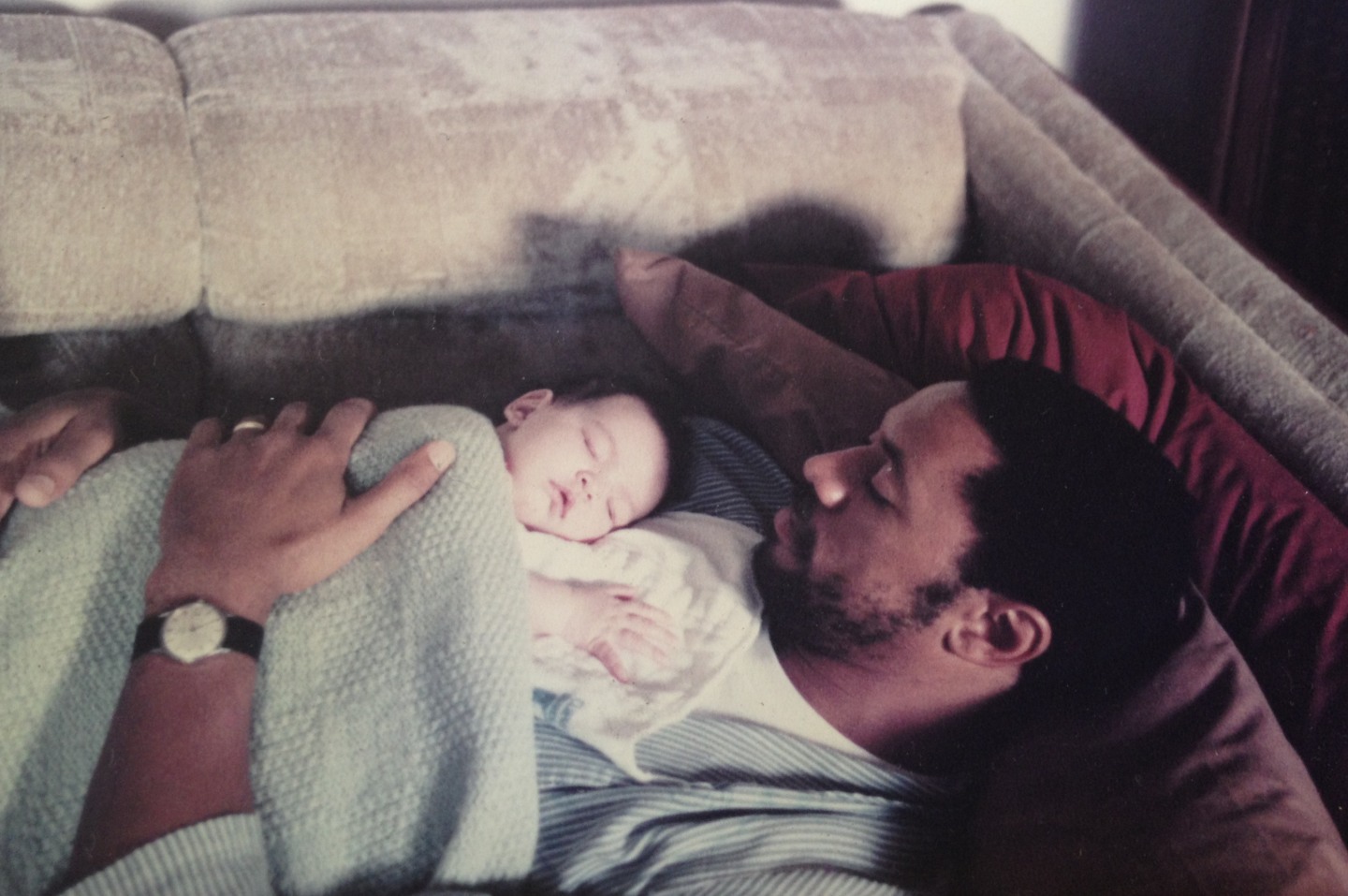

Rodney and Sadie Barnette.

Rodney and Sadie Barnette.

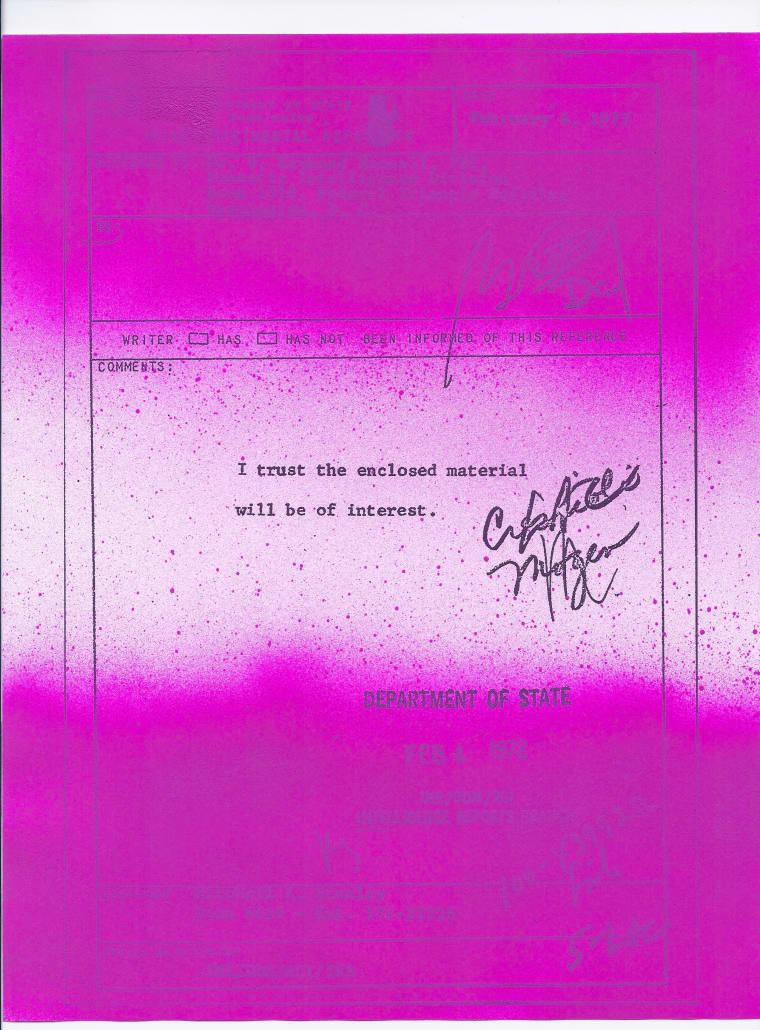

From “My Father’s FBI File, Project 1,” 2016.

From “My Father’s FBI File, Project 1,” 2016.

From “My Father’s FBI File, Project 1,” 2016.

From “My Father’s FBI File, Project 1,” 2016.

What did it mean to have your dad attend the opening and experience your take on his activism?

It was beautiful. There were also a lot of former Black Panthers there, and their children, Panther “Cubs” as they call them. Ericka Huggins — a prominent figure in the movement — was there. My dad has realized that this is living history and he needs to tell it. The government had my dad fired from the job he had at the post office. The surveillance was so intense, and I realized my dad was lucky to still be alive. And on a political level, the experience of this exhibition and telling my dad’s story has definitely made me more aware. J. Edgar Hoover said the most dangerous part of the Panthers platform was the free breakfast program, and if that’s what the government thought was dangerous — feeding young black and brown kids — we have problems.

You requested to receive you dad’s federal investigation files via the Freedom of Information Act. What was that process like?

It took about three years to get them. At first, my dad wanted it for personal reasons and I knew it would be amazing source material for my art practice. The thing that grounds my piece in the exhibition is how personal it is. Reading through the files it almost reads like a family tree. All the birthdays are listed, his military record, all these personal details. It was more than 500 pages. FBI agents from at least eight cities were involved. It’s a portrait of our family. I really wanted to flip it and re-appropriate it and use it to really tell our story.

I titled the Oakland Museum piece “My Father’s FBI File Project 1,” and I want to continue with that. Having it at the Oakland Museum made it feel like it had a good home; it contextualizes the piece. The 5oth anniversary gives it a framework. I grew up in Oakland and also spent time with my dad in Compton. My dad’s family was the first black family on their block in Compton in 1952. They were integrating Compton and it’s crazy to think about what they’ve seen.

There are a lot of sparkles and glitter in your work which, on the surface, is very ‘girly’ but there’s also more to it.

Escaping your reality is a big part of our culture today. Those materials also represent transcendence or escapism. The same way that people will adorn their nails or their cars. The glitter also had to do with that father-daughter conversation, and reclaiming this man who was being investigated as an extremist.

Works in progress in the artist’s studio, 2016.

Works in progress in the artist’s studio, 2016.

What role does music play in your practice?

Music has always been my biggest influence. I make art in service to music. If I had any musical ability, I would do that. Music is both realism and abstraction. That combo is real honesty. Prince, Sun Ra, Earth, Wind and Fire, and OutKast are some of my favorites, and I measure my visual art against that. I gravitate towards music that talks about outer space or Afrofuturism. Kendrick Lamar’s aesthetic is very of the moment. I love how he uses polaroids and images of washed out palm trees. We’re both a product of this combination of Black Power, N.W.A. and nerdy misfit kids — all these different references. Everybody from Compton is super proud to claim him. I love that his song “Alright” has become an anthem at protests!

Seems like we’ve come full circle. You could easily draw parallels to the politics of today with what was happening during the birth of the Panthers. You had the Vietnam War, the Black Power Movement, civil rights demonstrations, the assassination of Malcolm X, and much more. Nowadays, Beyonce is referencing the Black Panthers at the Super Bowl and activism is center stage. How do you see your role as an artists in all of this?

My dad says that, “When it comes to freedom, it’s not a progressive thing. You’re either free or not free.” So things have both changed and stayed the same. The optics are different today, the conversations are different. There are a few more zeros on people’s paychecks. I don’t think of myself as a traditional activist in the way my dad thought of himself. He was a pure activist on the ground. I think of myself as a researcher for the movement. People need music, poetry, creativity. They need to stretch their minds. Artists are key in this. Stay ready.

From “My Father’s FBI File, Project 1,” 2016.

From “My Father’s FBI File, Project 1,” 2016.