The End Of Period Shame

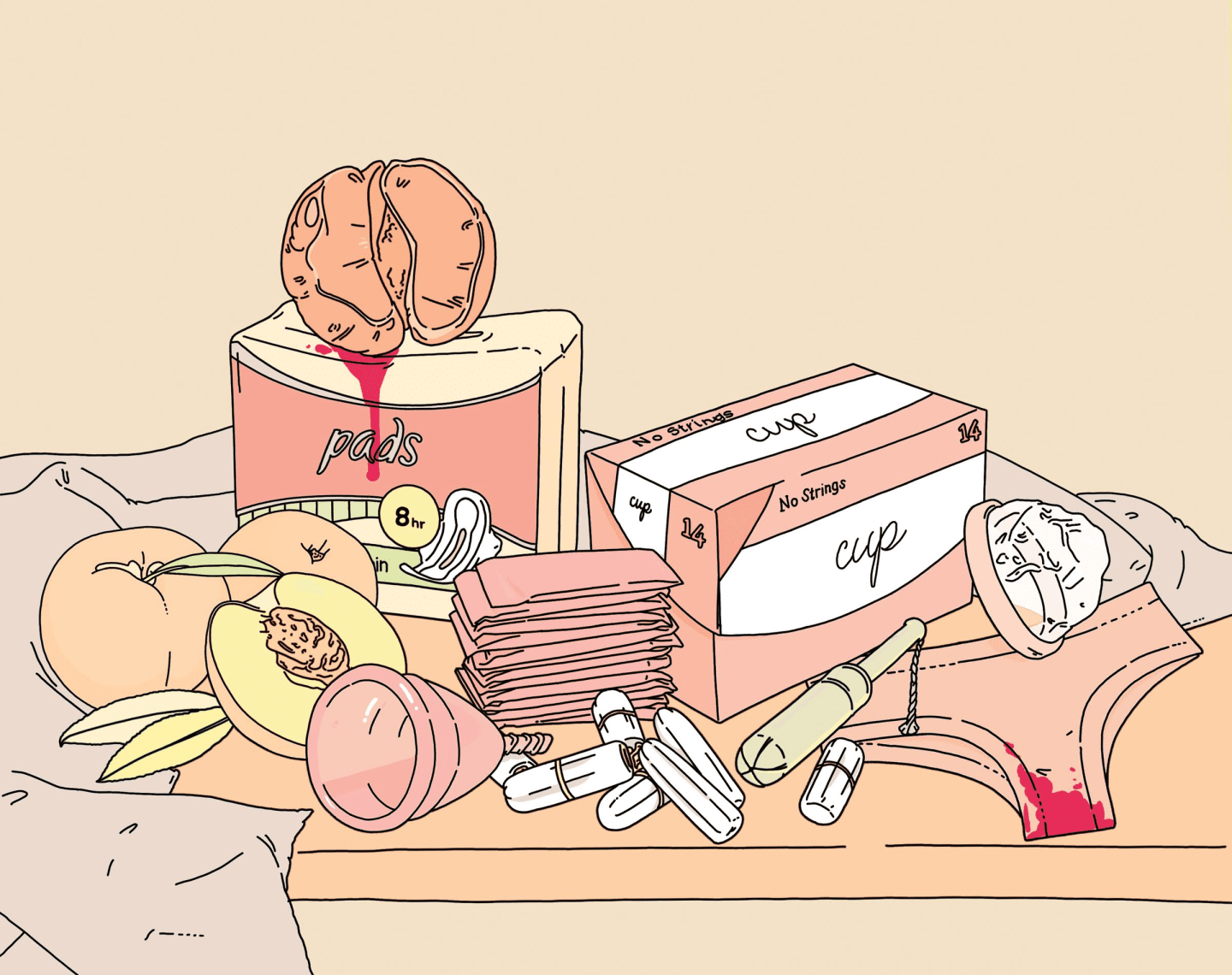

Artists, activists, and entrepreneurs are changing how we talk — and think — about menstruation.

There is a song on Jenny Hval’s new album, Blood Bitch, where the Norwegian artist slowly intones, Smells like warm winter. The lyric, from “Untamed Region,” refers to the blood the song’s protagonist finds on her bed, and dips her finger into, when she wakes up.

“There’s been so much talk in Scandinavia about the menstrual cup,” Hval said over Skype from her hometown of Oslo. The line was inspired by online discussions about the experience of using a cup, which isn’t doused in chemicals like disposable period products such as tampons and pads. “People were describing what [their] blood smelled like when there was no tampon or pad, and it was so different.”

Hval’s sensual song denounces the shame surrounding menstruation; the scent of expelled cells is recast as something relatable rather than a telltale sign of a millennia-old taboo. In a world where girls are taught from a young age that periods are supposed to be hidden — not just unobservable and unsmellable, but also unspoken of — the song presents an image of a woman who is not just unperturbed by her own blood, but emboldened by it. I have big dreams, she says. And blood powers.

“The strongest blood in the universe is probably menstrual blood. But at the same time, it’s always being stripped of power.” —Jenny Hval

Hval isn’t the only one shifting perceptions about periods into undeniably cooler territory. The past 18 months have seen a number of artists, activists, politicians, and entrepreneurs take radical strides toward dismantling menstrual stigma in a variety of ways. While feminist artists have been exploring the taboo for decades, today’s efforts are breaking out of the fringes and going mainstream.

In March 2015, Toronto artist Rupi Kaur posted a picture from her photography series period. on Instagram. It depicted a clothed woman lying on a bed, her back to the camera, with a bloodstain on both her sweatpants and the sheet. Kaur’s work broke the code of silence surrounding periods, and Instagram responded by deleting the photo. Undeterred, Kaur took to Facebook and Tumblr to write about the censorship, and the story went viral. (Instagram later apologized and reinstated the post.)

To Kiran Gandhi, a musician and activist who made headlines in August 2015 for running the London Marathon while bleeding freely, Kaur’s work is an act of “radical activism.” So, too, is the work of other artists helping nudge periods into the light: Argentinian artist Fannie Sosa incorporates menstrual cup advocation into her video work and teachings, while Los Angeles illustrator Faye Orlove included a diagram showing how to insert a tampon in her animated video for Mitski’s “Townie” earlier this year. “I like to confront boys with the ‘grossness’ of [periods] because I think it’s this cliché that girls are scared of violence and blood,” Orlove said in a phone call. “Do you even realize how much blood we’re confronted with regularly?” Acts like these, which force a conversation around periods, are crucial to combating stigma.

“The truth is that most social change doesn’t happen unless society is forced to question its problematic norms,” Gandhi said over Skype from her home in Los Angeles. “That’s why radical activism is so crucial: because it gives the media something to write about, it gives the people something to gossip about, and it gives people on Facebook a very tangible anchor around which to have this discussion.”

When the public starts talking about something — like it did last August, using #PeriodsAreNotAnInsult on Twitter in response to Donald Trump’s comment that Fox News host Megyn Kelly must have “blood coming out of her wherever” because she was tough on him during a GOP debate — commerce is never far behind. And that’s a good thing, believes Gandhi; product innovation is just as important to eradicating the period taboo as activism, access to education, and policy change. Because, along with the freedom that innovation brings, product marketing budgets are a powerful tool to reach people on a massive scale.

“The truth is that most social change doesn’t happen unless society is forced to question its problematic norms.” —Kiran Gandhi

That’s what happened in the fall of 2015 when Thinx, a line of period-proof underwear, plastered Facebook and N.Y.C.’s subways with ads that looked more like pages from a fashion magazine. It wasn’t just the photos but the accompanying text: “For women who have periods.” It turned out that the M.T.A. had originally refused the ads (no one had ever said “period” on the subway before), so Thinx went straight to the press. The media response forced the M.T.A.’s hand.

“The way we’ve been talking about periods is no longer clinical, medical, or academic,” explained Miki Agrawal, the New York entrepreneur who founded Thinx, over the phone. “It’s actually relatable. It’s like texting your best girlfriend. Because [Thinx] talks about it without embarrassment, it gives permission to others to talk about it in the same way.” Gone are the days of pad and tampon ads featuring blue liquid, a sanitized stand-in for rust-red blood. “The entire period space has been so tired and so lame,” Agrawal said. “[Now] it’s artful, it’s beautiful, and it’s culturally relevant.”

A fresh, modern look has also been important to Lunette, a menstrual cup brand founded in Finland in 2005 and now sold in over 40 countries around the world. Lunette’s founder Heli Kurjanen told me that the company’s clean and simple packaging has won it a lot of fans in transgender men: “There are lots of customers, especially from the U.S., that thank us that we don’t really focus on gender that much.”

The more we talk about periods, the less shameful we feel; and the less shameful we feel, the more powerful we are. That can translate to action: in July 2015, the Canadian government scrapped the “tampon tax” — shorthand for the sales tax added to feminine hygiene products because they were categorized as “luxury” items. In America, the 40 states that still tax tampons, pads, and menstrual cups are actively being challenged by campaigners. In a Facebook post this June, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio shouted out Council member Julissa Ferreras-Copeland’s hard work for menstrual equality, and announced that New York “is now the largest city in the country to guarantee free tampons and pads at public schools, shelters, and correctional facilities.”

“Women’s health is an economic issue,” Hillary Clinton wrote on Facebook in response. “Every woman deserves access to affordable menstrual products. Bravo, New York.” If Clinton wins the presidential election this November, maybe the U.S.A. will wave goodbye to the tampon tax once and for all.

In the wake of so much progress around periods, it’s easy to forget there’s a lot more work to do. “The strongest blood in the universe is probably menstrual blood,” Hval told me. “But at the same time, it’s always being stripped of power.” As Gandhi pointed out, we need art that works as activism to stir up uncomfortable conversations, as well as policy change to push forward innovation and take the conversation wide: it’s a cycle, just like the one that half the world’s population knows as intimately as their heartbeat. The coolest bit? In shrugging off our hangups, we’re not just helping crush a taboo; we’re raising a middle finger to the patriarchy and shaping a different future.