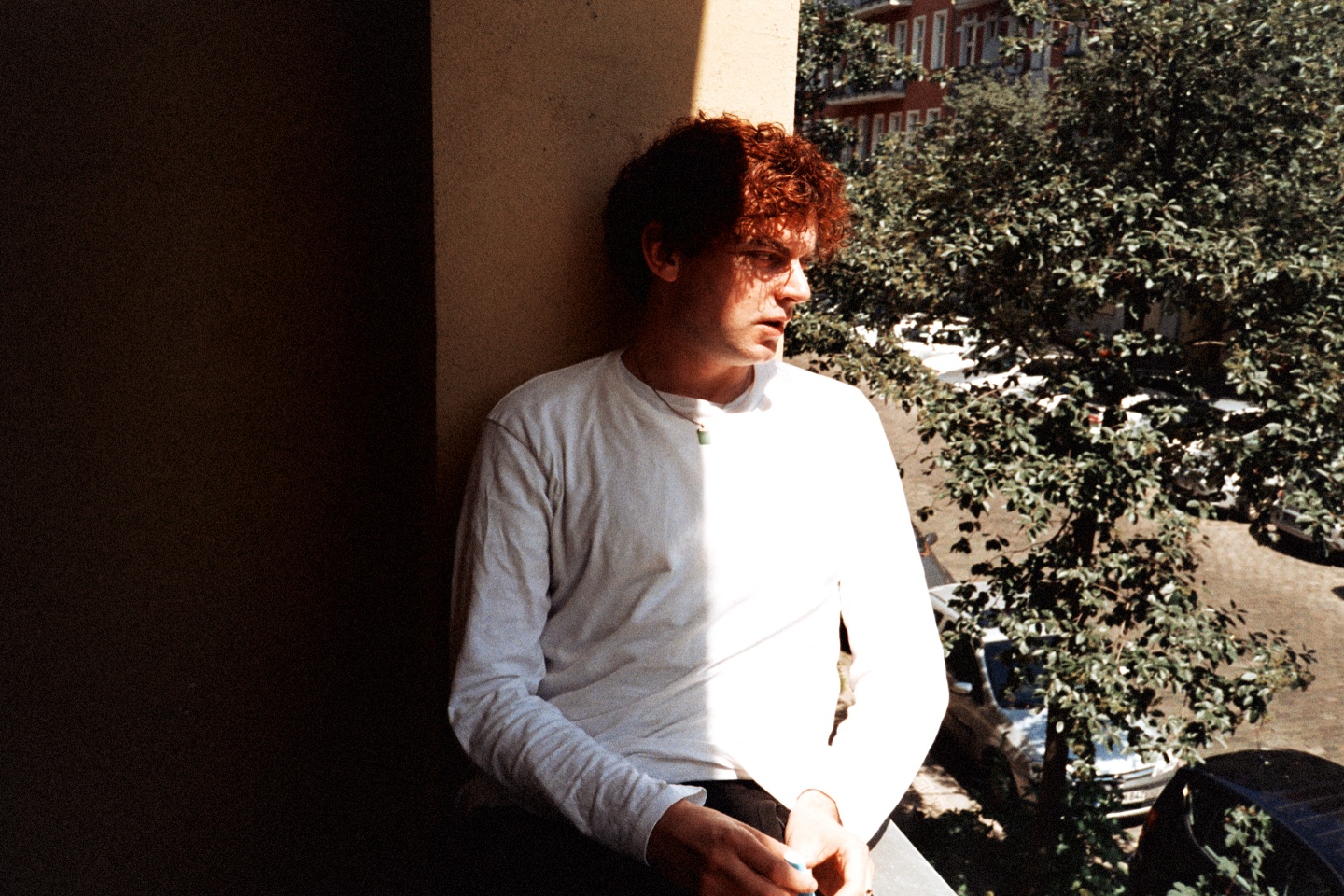

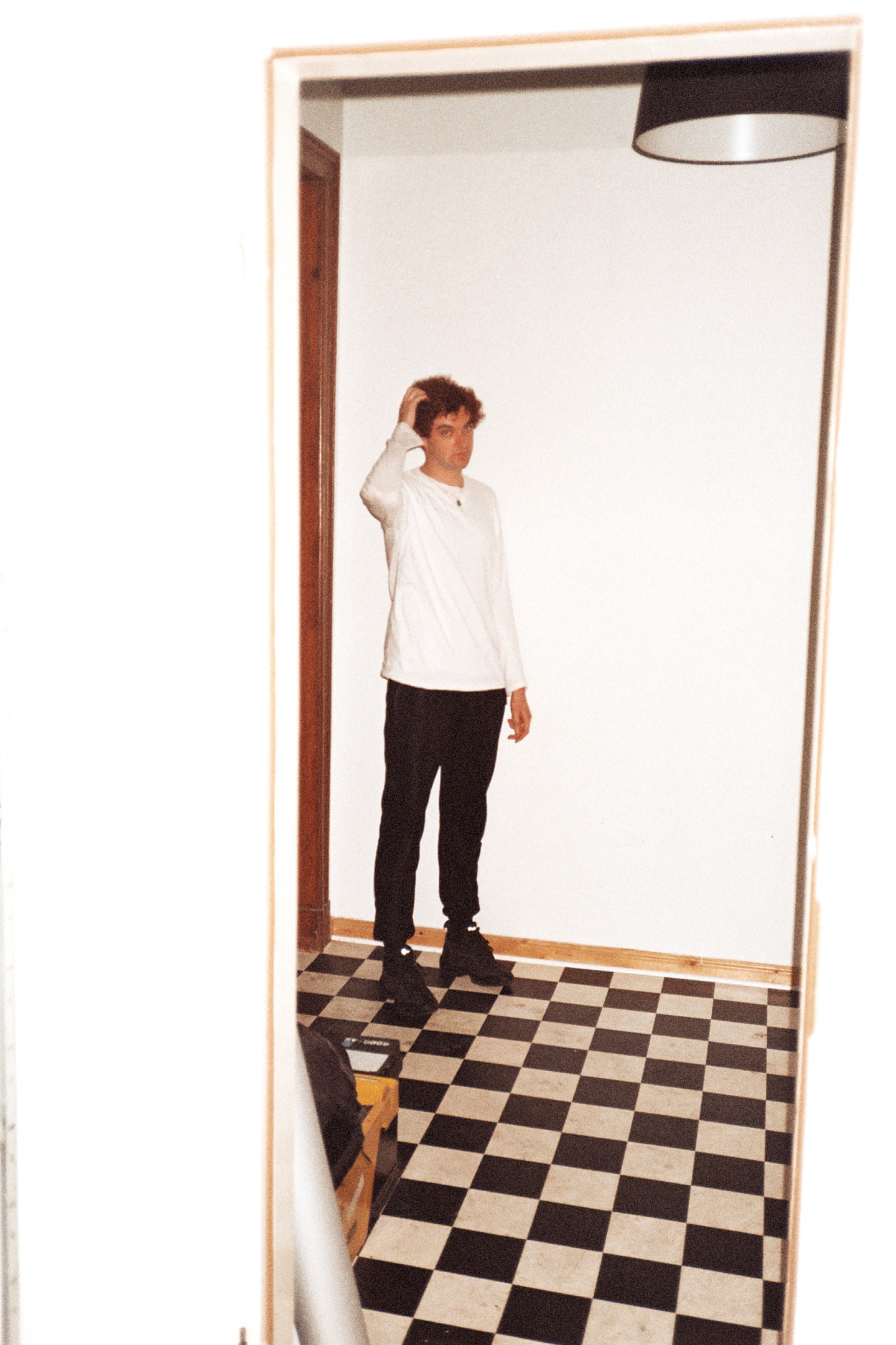

Meet Palmistry, The Outsider Making Party Music For Introverts

Benjy Keating, the pagan son of pastor parents, made a dancehall-inspired album about feeling happily alone.

The FADER's longstanding series GEN F profiles emerging artists to know now.

Palmistry’s parents, who are both Irish, met in a commune. When I spoke to the singer and producer, whose real name is Benjy Keating, over the phone from a loud cafe in his temporarily adopted city of Berlin, he described them as “hippies in the fashion of the late ‘60s, ‘70s.” His dad had found salvation in religion after spending time in prison. Together, his parents started a non-denominational Christian church in the Irish countryside, which was the first home that Keating lived in as a child. He said his family’s style of worship was “Americanized,” a severe contrast to their staunch Irish Catholic surroundings. The services would go on for hours, with music led by his mother. “There was an emphasis on healing in all its forms,” he remembered. “My dad was really focused on helping people who had been down and out like himself, and that kind of transcended the religious aspect of it.” He described the sermons as “radical,” intense,” and “lit.”

“Families didn’t really like our family,” said Keating. “It takes time, as a kid, to realize you’re weird.” His outsider identity only intensified when they moved to Peterborough, a cathedral city in the middle of England, when he was ten years old. He remembered Peterborough as a tough place, with a sense of segregation. He mostly kept to himself, until, as a teenager, he left his parents’s church, and moved to London to play in an industrial band. “I chose not to be a part of [my parents’] lifestyle anymore,” he said. “I was more outside, on my own.”

In London, where he frequently heard dancehall blasting out of car speakers, Keating found himself leaning away from industrial music, and towards the skeletal pop he makes now. When we spoke, Keating listed Vybz Kartel and Alkaline among his influences, but also mentioned religious English composers like Arvo Pärt and John Taverner, plus Ghanaian/Nigerian Afrobeats artist Mr Eazi.

Keating’s tendency to exist on the fringes has led the media to attempt to peg him to various scenes over the years. He has lived with PC Music producer Felicita, produced for Chinese rapper Triad God, and collaborated with Chilean electronic collective Bala Club — but his process throughout has remained defiantly singular. His self-released 2014 mixtape, Ascensión, combined some of the superficial textures of PC Music with earnest lyrics, a choral reverence, and Caribbean rhythms. His album Pagan, out in June via Dre Skull’s dancehall-focused label Mixpak, simplifies these characteristics even further, sometimes incorporating vivid instrumental interludes that recall ambient and trance. A recent New Yorker article described the record — which he wrote, performed, produced, and mixed all alone — as an example of a dancehall “revival.” But, as Keating explained, it’s not that simple.

“I don’t make dancehall,” he said. “Dancehall’s so pure as it is, it doesn’t need me to add anything to it.” His music shares rhythms with the genre, plus the occasional patois-via-London phrase. But he combines them, almost surreally, with sparse textures and lyrics about insecurity. Among the Mixpak roster, which includes Kartel and party-starting DJ/producers Murlo and Jubilee, Palmistry has most in common with Popcaan, the Jamaican artist whose spaced-out dancehall rhythms are laced with melancholy. But Keating's sound palette is leaner, more elemental, and unmistakably bleaker. While dancehall is often about connection, celebration, and reclamation of space, Palmistry songs are inward-facing. They’re not designed for the club, but for the lonely journey home.

This loneliness permeates Pagan. It wasn't surprising to learn that Keating spends a lot of time soaking up poetry; he was reading Rilke at the time of our interview, and named Zimbabwean poet Dambudzo Marechera as an old favorite. Palmistry lyrics can drift from outright darkness (most of my friends suicidal, Keating sings on “Sino,” his voice disarmingly sweet) to a reverence for sadness (the chorus of album closer “Sweetness” celebrates the sweetness of malady). There’s depression, a desperation to connect, and ultimately: a “fuck it” attitude. “Being an outsider formed who I am,” said Keating. “I feel like it made me a more interesting person. It’s difficult, growing up, but you kind of have deeper insight into things. Pagan is trying to embrace the positive side of that. ”