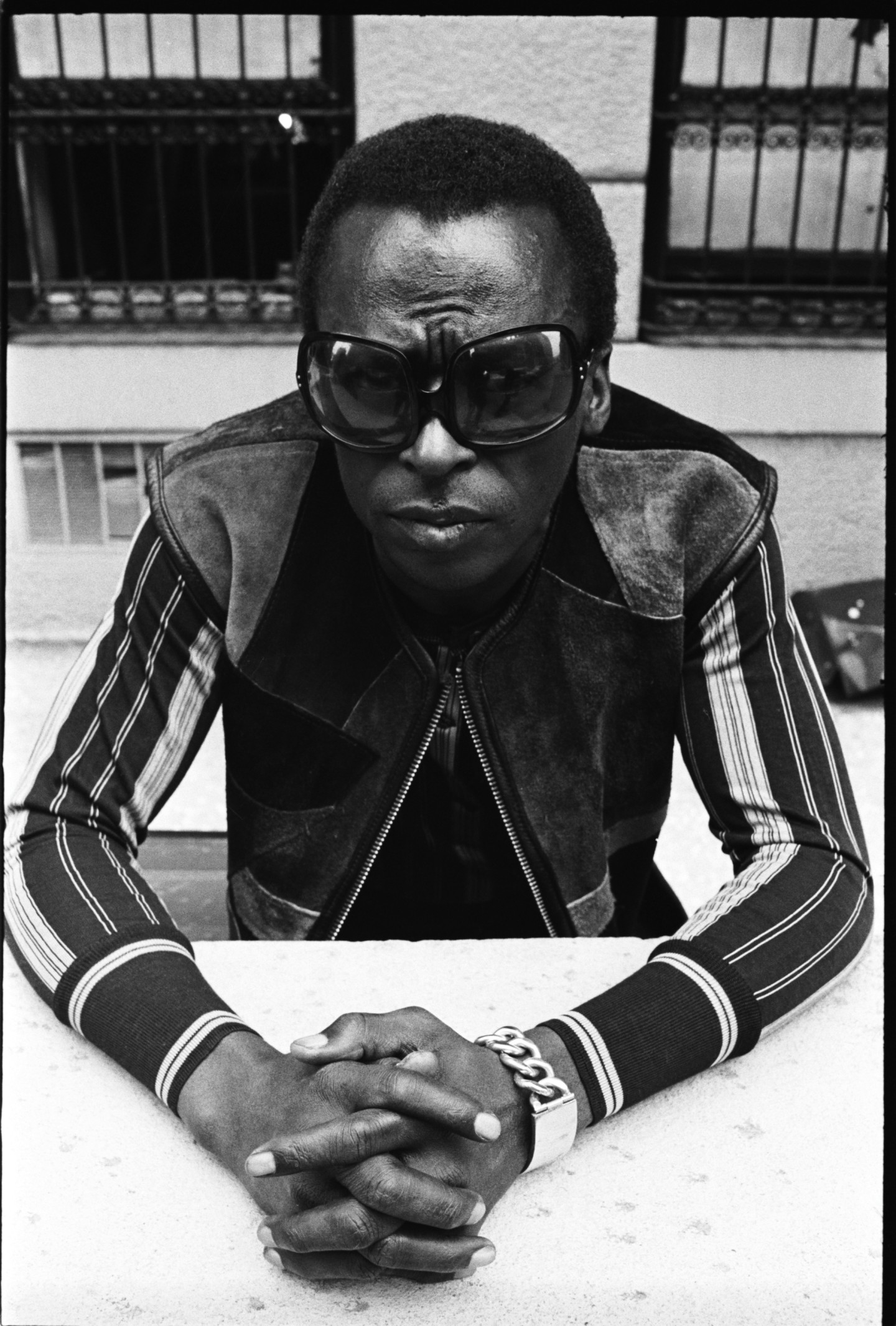

Don Hunstein

Don Hunstein

BRIAN CHASE (of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs): I took private drum lessons when I was young and my teacher introduced me to the jazz tradition and Miles. I transcribed all of Milestones and he had be transcribing Tony Williams's part on Miles Smiles. So my relationship with Miles is a very technical one, as a student of the jazz tradition.

I think of Miles as someone who was definitely not avant-garde, but he was cutting edge. For all his cutting edge-ness, Miles never challenged the traditional principles of jazz. But his bands redefined the repertoire of jazz music — instead of having the blues, like Gershwin-based song form, you have more complex harmonies and more complex melodies. More complex solo forms. A lot of that is Wayne Shorter's doing.

As far as fashion is concerned, I sense that Miles had a fear of being ugly. Anything mundane or lowbrow would offend him.. Mr. Slick Urbanite. It relates to his music too, this fear of ugliness. Ornette or Cecil Taylor's music is so far left of Miles that it can be unattractive to anyone in the middle. But he's different from people on the right side too — people like Lee Morgan or Jimmy Smith, who rely on blues-isms in their solos. That style never suited Miles. He had that hipper, intellectual quality to his music rather than something so down home and fundamental.

“Miles never created music to attract the audience. It was the other way around.”—Reggie Lucas

MOS DEF: The first Miles song I thought of was "Little Church." It's not an original, which is one of the things that makes it special — it's his interpretation of someone else's material. Everything that Miles did bears his mark, but "Little Church" is simple but lyrical, it's majestic but small. But majestic and small make for an exciting balance. It's delicate and strange and eerie and enchanting. And the thing about "Little Church" is that, it's not just a big solo — there's a dominant theme that he repeats over and over.

I miss Miles a lot and I wish he was here. A lot of the time it feels like I'm just here... I miss the creative context Miles might have provided. If anything we just need some new contexts to work in because the ones that are already well-established have been run into the ground. Now you just either subscribe to the existing contexts or you get out and stand outside, you know?

KAZU MAKINO (of Blonde Redhead): I'm not a jazz expert but I do have a strong relationship to certain things that have to do with Miles Davis, especially Betty Davis, who was Miles Davis's wife. She'd often sing about him and what he did to her — He used to beat me with a turquoise chain, and stuff like that. Very sexually explicit and amazingly dynamic music. I was so fascinated by her. I grew up to her albums.

I really like Waterbabies by Miles Davis and On The Corner. At first I just noticed the beauty of the album art and found myself drawn to it. But On The Corner didn't sound like a Betty Davis album at all. It was very free, but very genuine. It sounds like he really believed in peace; it sounds very humane. I think Betty Davis got me interested in him because of how she talked about him being over the top and outrageous. She's an amazing musician as well. I would have loved to have seen her play live.

“Miles had a different function, which was to express what was wrong and to make you feel it, and to make you feel your responsibility to it.”—Arto Lindsay

REGGIE LUCAS (guitarist on On The Corner and Dark Magus): I was playing guitar professionally at 16 and I worked up to the point where I had a road gig with Billy Paul, the singer. When I was 18, a friend of mine said Miles Davis is looking for a guitarist, so I went and had a brief audition at his brownstone on 77th street in New York. It was real simple. Miles said, "You wanna be in my band, motherfucker?" And I immediately said yeah.

We started out with a large band — electric sitar, tablas, Michael Henderson, Mtume. It was the best gig you could get, even today. We played all over the world with no set list — no song that we had to play for the audience because they would be disappointed if we didn't play it. Miles never created music to attract the audience. It was the other way around. We would have a melody, a head and some harmonic progressions that were sketched out. They were a template to be improvised on. None of us would be playing a solo or a lead, but we'd be evolving the harmonic and rhythmic structure of the song as it was being played. The more you do it, the more intuitive sections and segues you develop. The band would build up to these huge crescendos and then he'd throw up a hand signaling us to just STOP. Like an acid rock James Brown. It was his version of "HIT ME!" You never knew when it was coming and you never got fined if you missed it, but we got really good at it. We were all writing and composing onstage — continuous collaborative compositions and improvisations.

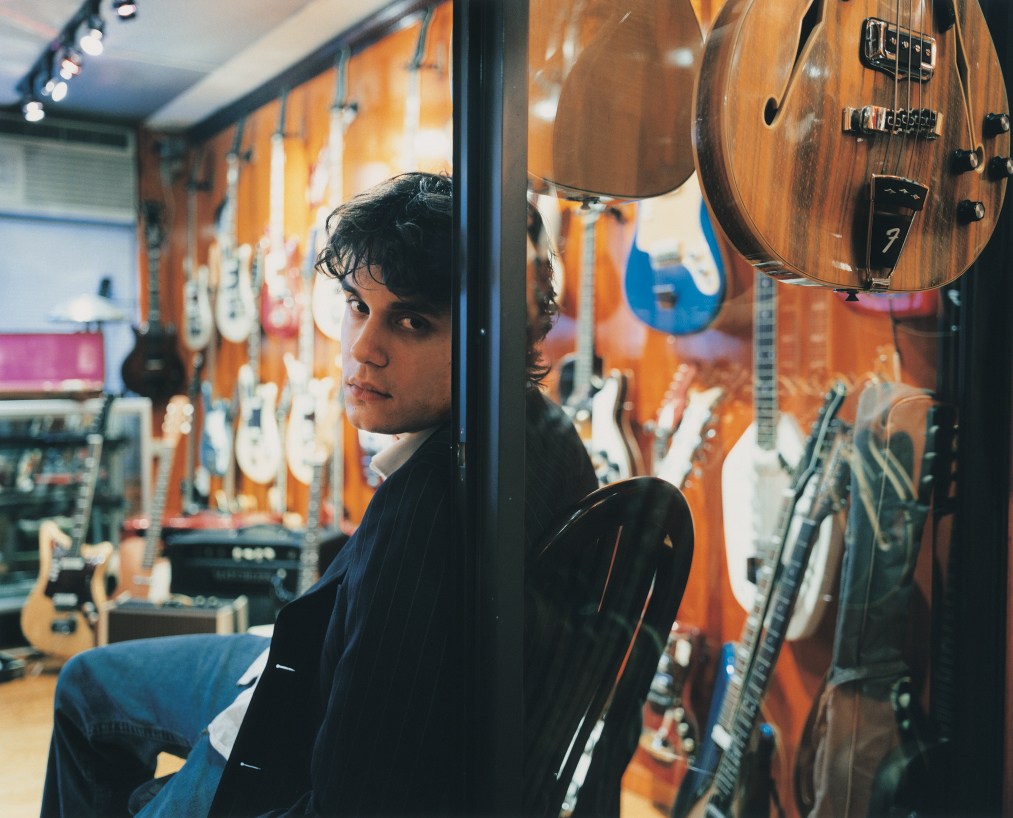

Madlib by Todd Cole

Madlib by Todd Cole

MADLIB: Miles Davis was one of the first artists I heard. When I was seven or eight, my grandparents showed me jazz music and who to listen to, so I knew about more jazz than hip-hop. Later, I looked at the Bitches Brew stuff more as something that I wanted to sample because it was just weird — it sounded like a big freestyle or something. I used to sample his wah wah trumpet a lot and we was doing some crazy stuff with it. More recently I've been trying to keep up on all the '80s stuff. I had all of it, but I hadn't really listened to it — Decoy, and those live albums. My favorite period was with Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, and Tony Williams.

I read that autobiography by Quincy Trope and learned a lot. Miles was just like a hip-hop cat, but in the jazz days. I know a couple cats like him — not exactly like him, but kinda odd like that. I'm surprised those jazz cats lived through some of the shit they were doing. They were like rebels.

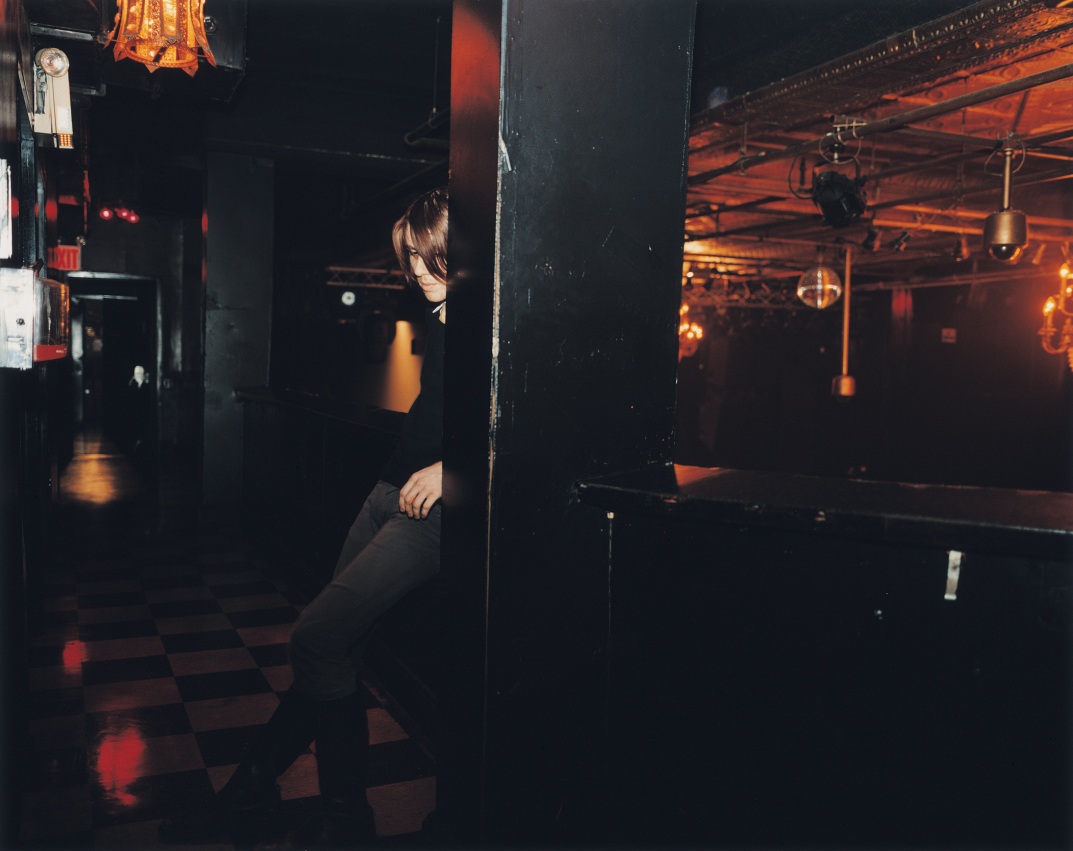

Benjamin Curtis by Juliana Sohn

Benjamin Curtis by Juliana Sohn

BENJAMIN CURTIS (of The Secret Machines): I think the first comparison I heard in reference to my own guitar playing was Pete Cosey, and I was like "Who's that?" So I went back and checked and thought, "Yeah, I kind of do play like that." While listening to Cosey play on those records, I realized that everything I listened to was probably influenced by Miles Davis — from Gong to Tortoise to Spiritualized.

But the thing I think about the most is how a lot of people say "That person can't really make records, he just gets other people together to make his records." But you can really look back to Miles Davis and find that his personality is at the center. It really is a Miles Davis composition. You take any of those sidemen out and they never played like that without him. Weather Report is a brutal disappointment, and Herbie Hancock doesn't quite make it. There's something about Miles Davis standing there. I think Bjork makes records like that. The person I mentioned was talking about Bjork. You know, 'Bjork can't make a record, but she can get other people together to make a Bjork record for her.' But I've never heard anyone else make a Bjork record. Miles is the perfect example of that.

“With Miles Davis, the art form was the evolution and through that he pissed a lot of people off — as soon as you finally understand what he’s doing, he changes it.”—John Mayer

DAVID BANNER: I got into everything from jazz to techno to country as a producer who was sampling. When I was at the University of Maryland, I'd pick a record up and sample it, then put it back in the cover and throw it on the floor. So there'd be a pile of records there for weeks. Then I'd do a clean up on Saturdays and put the records on to look for more samples, but I couldn't skip through them because I was cleaning. I ended up becoming a really big fan of Miles Davis, Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, all of those dudes.

I love Sketches Of Spain because it places a mood on me. A lot of music sets a certain kind of feeling, but it doesn't have a specific mood that it puts you in, you know? You might have one song that makes you feel angry, but you might have another that puts you in the mood to kill a motherfucker. Sketches Of Spain didn't make me happy or somber — it put me in a melancholy, displaced kind of mood.

When I was looking for stuff like Sun Ra, Bitches Brew fell right into that. One thing rappers can't really do right now on a commercial level is step out and be individuals and do their own thing like that. I listened to Eminem's 'Stan' on the radio and that's not your everyday ordinary single — that's your favorite cut that you don't really want anyone to hear because you love it so much. When you put a track like that out as a single and it does well, that's Miles's shit. People like Miles and Sun Ra wanted to go against the grain and they had a fanbase that would let them do that. That's what Outkast has today.

John Legend by Michael Schmelling

John Legend by Michael Schmelling

JOHN LEGEND: To our generation, Miles just represents cool. You look at the pictures and all the photography made him look like an icon who had his own unique thing and was so cool and comfortable in that thing. He was a trendsetter, and the images you see around him suggest that — the fashion and the quality of the photography and the music together project a classic sense of cool.

I listened to Kind Of Blue all the time when I was in college, especially when I was studying. It's just so well put together — the music, the melodies, and the arrangements are all very subtle. I remember pretty much every moment and I can hum along to the whole record even now. It's all in my head, and any album I listened to that much has to make some impact on my own music.

John Mayer by Juliana Sohn

John Mayer by Juliana Sohn

JOHN MAYER: The thing I love most about Miles Davis is that most artists' evolutions are secondary — there is some kind of after effect where you look back and are like 'Oh, I guess I kind of changed from there to there.' But with Miles Davis, the art form was the evolution and through that he pissed a lot of people off — as soon as you finally understand what he's doing, he changes it. It was like when he finished the record he had completed the thought. The record was like an experiment and once the record was done the experiment was over, and that's so counterintuitive to what pop music or actually music in general is today. Another thing I really respect about that scene is the community. You could have trading cards of those guys. Even later on in his career, Miles served as a lionizing force for other musicians like John Scofield and John McLaughlin. Anybody who passed through was knighted. One of my favorite periods was the quartet — Milestones is a gorgeous record, and a gorgeous tune, actually. There's also On The Corner. It's not an all-the-time record, but if you want to feel that vibe that probably was in the air for a couple years in the '70s, that's where you go. It's the sound of — I just picture old cars and gas shortages and what everyone thought they wanted to be for a minute.

“He was a visionary as far as our future exploits in hip-hop... it’s like he’s right here with us. The man was like a Tupac. Or more like, Tupac was a reincarnation of him.”—M1 of Dead Prez

JAMES MURPHY: I'm not a big Miles guy. Everybody goes blah blah blah, Bitches Brew. But it's not really my thing. I just always found him in between — marginally unpleasant and tediously populist and not quite funky enough for me and not quite beautiful enough for me. His cool stuff I find not that different from the California cool stuff, which is just plain silly and posture-y. His crazy stuff I find not as crazy or interesting as Ornette Coleman; his spiritual stuff has not touched me like Alice Coltrane or Pharaoh Sanders. I'd rather hear Sly Stone than Bitches Brew. I feel like he's the Emperor's New Jazz Hero; it's like if you say you don't like him, you're some kind of heathen. And because he's a good mythologist people act like the individual records are actually better than they are. He set himself up very suavely as an icon, but I'm not that interested in iconography really. It's like, if the Velvet Underground were that good, it would just be Lou Reed. But they were that good — just plain old that good — and Lou Reed made songs that were some of the greatest pop songs in history. I'm sure I'm going to get fucking hatemail for this, but Miles Davis just always felt neither here nor there for me. Although he did write the line that Jesus Lizard ripped for "Then Comes Dudley."

M1 by Lauren Fleishman

M1 by Lauren Fleishman

M1 (of Dead Prez): Miles was a bad, bad, bad, bad dude; an international figure with a reputation for making cutting-edge music and having the most eccentric ways, but he still had a connection to the people — and he represented and championed the community. That makes records like On The Corner special to me; Miles in Harlem running around with all these dudes — black dudes who were doing some really against the grain shit but doing it because revolution was a main theme in the world at that time. There's stuff people don't get from Miles. I just got the Bitches Brew box set, and it contains two or three CDs of [previously unreleased] sessions that no one ever really heard.

There's this one song in particular called 'The Little Blue Frog,' and for him not to put that song on the album showed that he was more than a musician; he was an exercise in in discipline. He represented a kind of discipline in the arts that's not here anymore. Sony's releasing more Miles material now, and there's stuff remastered into it — more drums, military cadences and other drastic moves. I just love it, and it shows you how much of a visionary he was as far as our future exploits [in hip-hop]... it's like he's right here with us. The man was like a Tupac. Or more like, Tupac was a reincarnation of him.

“When Miles Davis embraced hip-hop by doing the join with Easy Mo Bee and all of that, it gave hip-hop a chance; it expanded the breadth of the music.’—DJ Premier

DJ PREMIER: When Miles Davis embraced hip-hop by doing the join with Easy Mo Bee and all of that, it gave hip-hop a chance; it expanded the breadth of the music. Miles was married to Cecily Tyson, who was one of the best black actresses in the entire world. And I heard he was crazy. When I worked with Stanley Clarke, the bass player, he told me some crazy stuff about him going to Miles's house and Miles answered the door with a gun in his hand, butt-ass naked with a hard dick. He was like, "What the fuck you want man, why you at my door?" And he knew Stanley Clarke! But, you know, the most eccentric and creative people are geniuses anyway. I'm a little bit like that as well, but I'm not going to answer the door with a gun in my hand, butt-ass naked.

I'm way more into Miles on a live level because he always has that big-eyed look that's like, "Don't ever mess up around me." You know that's what I take from him — work ethic. It's all about giving the people all of you in the record format and all of you in the live format and then be gone — you don't owe them nothing else.

Miho Hatori of Cibo Matto by Juliana Sohn

Miho Hatori of Cibo Matto by Juliana Sohn

MIHO HATORI (of Cibo Matto): The first Miles Davis album I got was Bitches Brew —I was working in a record shop and I was curious about the album cover. It was like I needed it — it's totally magnetic. So I listened to his music and I felt like the cover art and the music literally made sense together, you know? It's like I knew what I was in the right spot in life. When I hear Miles's music, it's almost like I'm telling my own story; it's like I have a seed or a plant and it becomes a tree and there are people kissing and having babies, and they are going to be big soon or whatever. It has this very universal energy.

Eventually I went to his earlier stuff like Kind Of Blue, and somehow he didn't change that much. He had himself from the beginning — there were so many different sounds, but his approach wasn't changing. He started his career in the '40s or '50s and America was still having the problems with racism, then in the '80s he's wearing the golden jacket with the shoulder pads. I like to buy the vinyl because a lot of jazz critics in Japan are very good, and through then I can understand what's behind the other players, and how exciting it must have been in New York, and how amazing it would have been to have played with Miles Davis.

“When I hear Miles’s music, it’s almost like I’m telling my own story; it’s like I have a seed or a plant and it becomes a tree and there are people kissing and having babies, and they are going to be big soon. It has this very universal energy.”—Miho Hatori, of Cibo Matto

VIC CHESTNUTT: I played trumpet when I was a kid — I started in the fourth grade and played through high school, so Miles certainly loomed large. Nobody was cooler than Miles Davis back then so it made me feel good that he played my instrument. There were other really popular horn players too — Doc Severinsen was on the Tonight Show — but Miles had hit records and an aura of danger about him that Al Hirt and Doc Severinsen certainly didn't have. As a young kid in the South, for me that danger was really appealing. I remember hearing the records — Kind Of Blue and stuff like that —and it wasn't just your standard Ba da dat dat da da da. It was kind of groovy and it was shocking because he had delay on that stuff. Which is like, "What the hell?" Doc Severinsen didn't have no delay on his trumpet.

When I was in my 20s, I read Miles's autobiography, which blew my mind and was a big, big book for me. I realized that I wasn't such a freak for saying "motherfucker" all the time. And I really liked the way that, at a time when Bird and Dizzy and those guys were in this testosterone-fueled race for speed, he was a ballad player. A really adamant, dogged ballad player. For me as a folk singer in the days of punk rock, he was someone to emulate. "Yeah, I can play ballads, and I can be cool and fierce." A ballad can be fierce. With Bird and those guys it was just all about the dick. It was really about a "my dick is bigger than your dick" kind of thing. Miles was full of the dick like the rest of them, but his music was pretty. That really appealed to me.

“The band would build up to these huge crescendos and then he’d throw up a hand signaling us to just STOP. Like an acid rock James Brown.”—Reggie Lucas

DAMON ALBARN: Miles Davis attacks, especially on records like Bitches Brew and On The Corner. Some of it's toxin and some of it's anti-toxin, but you could listen forever because of the way it's been put together. I suppose there were bands like Can doing something similar, but Miles was taking huge chunks of recordings and really chopping them, then piecing them together. It seems like such an obvious evolution from there to where we are now, but that was like 10 or 15 years before the technology was available. And that's exactly what a leader should do — you should hear a leader say, "And I've seen into the future." I've had three phases in my Miles Davis listening — when I bought the records I was younger and felt that I really had to listen to them, and forced myself through it. The second time I was a bit more familiar, and this time, well, I'm in there now. And the message is that in order to actually understand the music and involve yourself in it, you have to learn the language.

ARTO LINDSAY: I saw Miles play a lot of times. I saw him at Café A Go Go on Bleeker Street and to get into the narrow room you actually had to walk past the band. So I used to hear this guy playing all this Brazilian stuff and I didn't know Airto Moreira was in the band and I was totally blown away, the guy was singing all these folk songs, doing whatever he wanted no matter what was appropriate for the song.

The music that more directly influenced me was on Get Up With It. It has calypso and all that; much harder and fragmented with different kinds of rhythms happening at the same time — funk rhythms against Indian or other ethnic kinds of drums. The Bottom Line was kind of remarkable because the conductor was Mtume on congas and the whole thing was coordinated around him and Miles just came in and out and communicated to Mtume and Mtume communicated to the band. It was really deep because it was so master drummer-like.

There are no pop culture figures like Miles anymore. For one thing the very figure of the angry black man has been turned into a cartoon by several generations of rappers — it's all theater. And although New York is so different now, there's still plenty of the kind of pain out there that Miles was expressing, and I don't see anybody really doing it anymore. You know, Miles Davis was not Peter Gabriel. He wasn't a do-gooder trying to raise money to raise consciousness. He had a different function, which was to express what was wrong and to make you feel it, and to make you feel your responsibility to it. He was an intense dude and there was so much hate in him, his whole thing was so sexual but it wasn't macho, and of course years later we learn he may have been bisexual. But at the time it was just this thing that hit you, this force that hit you that you didn't understand.