For this year's Icon Issue, it quickly became clear that we couldn’t possibly cover every single piece of work Philip Glass has made. But in talking to his friends, collaborators and people influenced by him, we realized that there was a common thread: his soundtrack work is often a perfect gateway into his music. Here are nine Glass scores for nine very different films.

For this year's Icon Issue, it quickly became clear that we couldn’t possibly cover every single piece of work Philip Glass has made. But in talking to his friends, collaborators and people influenced by him, we realized that there was a common thread: his soundtrack work is often a perfect gateway into his music. Here are nine Glass scores for nine very different films.

Dracula, 1931/1999

Actor Bela Lugosi’s rendition of Count Dracula in Tod Browning’s classic 1931 film may have indelibly changed the way all vampire counts would speak for all time—even the ones on cereal boxes and Sesame Street—but Philip Glass paid no attention to horror tropes when he was tasked with writing a new score for the film. As he saw it, “The score needed to evoke the feeling of the world of the 19th century—for that reason I decided a string quartet would be the most evocative and effective. I wanted to stay away from the obvious effects associated with horror films. With [Kronos Quartet] we were able to add depth to the emotional layers of the film.” He does manage to give the score an appropriately 19th century feel—but underneath there’s that very modern, uncanny and dread-inducing Glassian sense of repetition that will make your hair stand up on end and your blood go cold. Though, depending on whom you ask, maybe not as effect-ively as Music in Twelve Parts. AB

Stream: Philip Glass, Dracula score

Koyaanisqatsi, 1982

I first heard “Vessels,” a vocal piece from Godfrey Reggio’s film Koyaanisqatsi, at a fashion show. I did not know what it was. I also had never been to a fashion show before. The show was on the west side of Manhattan, a few stories up, with a good view of the Hudson River and across to New Jersey. Patrik Ervell, the designer, makes clothes that, while not ethereal, are lithe and new. Watching models strut to such hearty and beautiful singing generated within me unexpected (though not unwelcomed) awe. I later saw Koyaanisqatsi and was surprised to see the film itself is also about awe, though not necessarily beauty. Without any dialogue, it moves from the creation of Earth to the development of industry to all of the rotten things that follow. If there is terror in the music to match the images, it’s sublime, not a representation of death, but of a near-death experience. With Glass’ score, Reggio goes from being a doomsayer to a caretaker, a crucial tweak towards the light. It makes models look good, too. MS

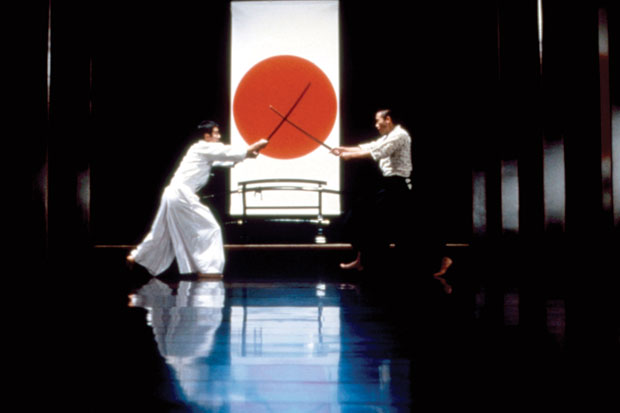

Mishima, 1985

Glass’ score for Paul Schrader’s mosaic biopic Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters examines the life of a major public personality, Japanese author Yukio Mishima. The score, written for string orchestra and percussion and recorded by the Kronos Quartet, mingles husky cellos with brittle, marching snares and tornado violin swirls. On “Temple of the Golden Pavilion,” fast, repeated phrases are overlaid with one-strum bright notes. The score’s first half culminates in “Kyoko’s House” a five-minute surf rock lullaby propelled by climbing strings and butterfly kiss violin plucks. It may allude to the anxiety of post-war Japanese youth, but it evokes the restless energy of people everywhere. “Kyoko’s House” is often used as a background theme in This American Life, the weekly radio program whose silver fox producer/host, Ira Glass, is Philip Glass’ first cousin once removed. NZ

The Thin Blue Line, 1988

Operas are essentially narrative plays set to great soundtracks, but Philip Glass killed that precedent, writing music that was often beautiful, but consistently bucked expectations. The Thin Blue Line is a documentary about a controversial Texas murder trial that proceeds like a scarier version of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. On its soundtrack, you get a strong sense of story and narrative through his foreboding, flourishing strings. One track is called “The Electric Chair;” another is “Hell on Earth.” It’s hard to listen to, but it feels connected to the ancient Greek choruses of Sophocles or Bizet’s Carmen, yet completely relevant to our own contemporary fears and personal melodramas. AF

Candyman, 1992

When you talk to a lot of people about Philip Glass, they talk to you about Steve Reich. It’s not a matter of picking your favorite Beatle (they’re both George), but the divisive aesthetic split between the two, who started in a similar place and were once close, makes many people choose sides. (Reich declined our request to be interviewed for this issue.) I feel as though the fact that Glass made the soundtrack to Candyman, as well as its sequel, is emblematic of their divergence. Just three years prior to Glass’ horror movie foray, Reich made Different Trains, his epic piece about the Holocaust. But Candyman is more than a marker of Glass’ indiscrimination between high and low culture and more about his willingness to try anything, even if it is questionable. “It Was Always You, Helen,” the Candyman theme, is hokey but effective. So is the film. It’s as hard to find fault in that as it is to find any in Reich’s career-long seriousness. MS

Stream: Philip Glass, "It Was Always You, Helen"

Kundun, 1997

The signature point of Philip Glass’ Kundun score is a heavy gong that punctuates nervous strings and drags out into a staccato rattle. It’s as close to terrifying as sound can get. You know it’s coming, you know when it’s coming, but that doesn’t make it any easier to hear. It sounds serious, it sounds ancient, and it does what any great score should do: it says, here is an important film with music to match. Usually with these scores, the second they get taken out of their original context, they’re so memorable as to become glaringly obvious. When that terrifying gong got reused on a recent episode of Parks and Recreation, it wasn’t so much obvious as it was hyper-disorienting. Picture a sad Rob Lowe sitting on a small town stage at a Valentine’s Day mixer, the score to Kundun blasting from an iPod while a bunch of couples shuffle around looking confused. Aziz Ansari’s character comes up to him and says, “This kind of sounds like the end of a movie about a monk that kills himself,” and Lowe responds, “It is.” Even in moments of awkward comedy, Glass’ music for Kundun can’t be separated from its original intent, and that’s the highest possible compliment there is. SHS

The Hours, 2002

Only Philip Glass could take a film about the interconnected lives of three bummed out women and turn its score into something that would work just as well for soundtracking a drugged out trip to the Planetarium to hear Tom Hanks narrate a journey through the galaxy or whatever. Despite the fact that The Hours soundtrack sounds almost cosmic and is wedded to a film that is the exact opposite of cosmic, the score is classic Glass: there’s tense repetition that builds and layers to a breaking point that never really comes. Instead, the piano blooms and expands elastically into something that feels revelatory. As a soundtrack, it’s close to perfect, but as a piece of music independent from the film, it’s possibly better. You know how sometimes someone (a Hallmark card) will say that life is about the small things? They’re not wrong, but if this score tells us anything, it’s that life is actually about things so huge that they can’t be put into words, just made into beautiful, beautiful music. SHS

Notes on a Scandal, 2006

Notes on a Scandal is a torrid story of lust and betrayal. In the film, Dame Judi Dench and Cate Blanchett both play despicable teachers. Dench’s Barbara is contemptuous and unhinged, Blanchett’s Sheba is ruined by an affair with a 15-year-old student. A sour oboe theme stands in for Barbara, who narrates much of the film’s first half. When she and Sheba meet, on “First Day of School,” the oboe is out front, rising over a signature-Glass rhythm of pulsing strings. Glass’ melodic writing takes the spotlight for much of the score, oboe leading “The Promise” and standing in for “Sheba’s Longing.” But Glass conjures the second half of the film’s suspense with fat drums. On “Confession,” the low strings play fast, frantic notes while the high strings hold long, piercing notes. On “Betrayal,” percussion thuds interrupt and temporarily halt frenetic rhythms. It’s a testament to the score’s power that just by listening to it, you feel manipulated and a little sick. NZ

No Reservations, 2007

Philip Glass has a thing with wives. He’s had a lot of them, maybe a result of his workaday (or work-all-day-and-night) lifestyle, or maybe a result of his self-proclaimed ineptitude in the realm of romance. But when someone once asked him if he’d ever write something for such a throwaway genre as rom-com, he said, “I’d love to! I’d have no idea what I’m doing and that’s the best situation for a composer to be creative.” So, in keeping with his ever-churning pool of creativity, Glass challenged himself with writing a score for a film about an ego-maniacal chef who unexpectedly finds love and humility after a shocking tragedy. For the most part, director Scott Hicks’ (who, it should be noted, also directed Glass: A Portrait of Philip in Twelve Parts) No Reservations was panned by critics, but the score might still serve as a little window into why many of Glass’ relationships don’t work out: It’s all Glass, all the time. AB

Stream: Philip Glass, "Zoe Goes to the Restaurant"