Mary In The Junkyard

Steve Gullick

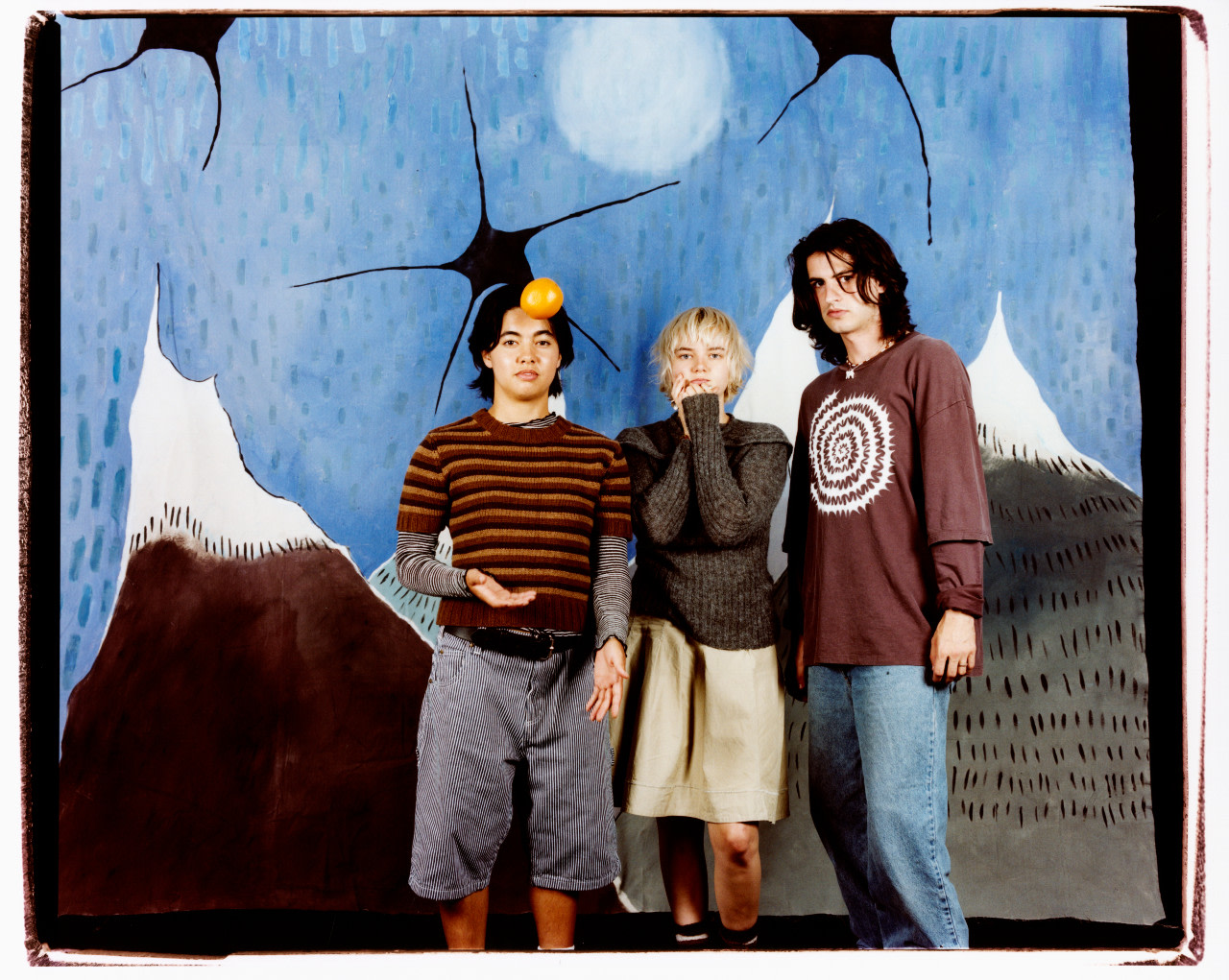

Mary In The Junkyard

Steve Gullick

The Opener is The FADER's short-form profile series of casual conversations with exciting new artists.

Clari Freeman-Taylor grew up in the remote English countryside, isolated and with enough time on her hands to let her imagination run wild. “Growing up I had a lot of fears and would dream up monsters,” she says over Zoom. “There’s this whole imaginary world I would use to break away and escape.” When she got older and formed the band Mary In The Junkyard with drummer David Addison and bassist Saya Barbaglia (who are also on the video call), she returned to the anxieties of her youth for This Old House, their debut EP. “The songs have a real feeling of claustrophobia,” she says from her new home in London.

The line between childlike imagination and unvarnished horror is one Mary in The Junkyard skip over merrily on This Old House. The sweeping art-rock “Marble Arch” conjures images of lonely nights and frayed sisterly relationships. The desperate longing of adolescence can also be felt above the gothic waltz of “Teeth”. There is a rabid nature to “Ghost,” too, and not just because the band howl some of the backing vocals. Freeman-Taylor describes that song as being initially written while she was “obsessed with moths” but is more reflective of moving to the city and “enjoying the freedom” she desired as a teen. The band cite Joanna Newsom and Leonard Cohen as influences, though the fantastical darkness of a director Guillermo Del Toro or novelist Shirley Jackson feels just as apt a reference point.

This black-laced vulnerability has made Mary In The Junkyard one of the must-see live acts in London over the past 18 months. In the band’s estimation, they played the Brixton Windmill, a venue key to the rise of acts such as Black Midi and The Last Dinner Party, over 30 times as they happily snapped up support slots. Like fellow Windmill alumni Black Country, New Road, Mary in the Junkyard met while studying orchestral music and used their downtime to write what they describe as “silly songs,” pop-oriented material a world apart from both the classics they studied and the “angry weepy chaos” music they would go on to make together. One early memory they have of playing together is a cover of Radiohead’s “Creep” performed with spaghetti as drumsticks.

Steve Gullick

Steve Gullick

The man who helped them refine their anything-goes energy was Richard Russell. The band decamped to The Copper House, a south London studio owned by the XL Recordings founder, and got to work at the start of 2024. They set up their equipment in the studio’s kitchen, joking on the call that they wanted to make “kitchen rock” the new bedroom pop. Addison says Russell helped the band shed their perfectionist tendencies while Barbaglia echoes that she was impressed with his laid-back approach. “He's a very spiritual man and I think after a week with him, I felt just so at ease. That kind of mindset was really inspiring and made me realize it’s the way it’s meant to be.”

Barbaglia describes occasionally feeling “exposed” by performing now. The band prize their live show above almost everything but concede that playing such intimate songs can be hard. It’s something Freeman-Taylor says she often wrestles with too. “I don't know whether it's really therapeutic or just kind of fucks you up,” she admits. Either way, that high-wire chase for catharsis is what makes the band’s songs so magnetic.