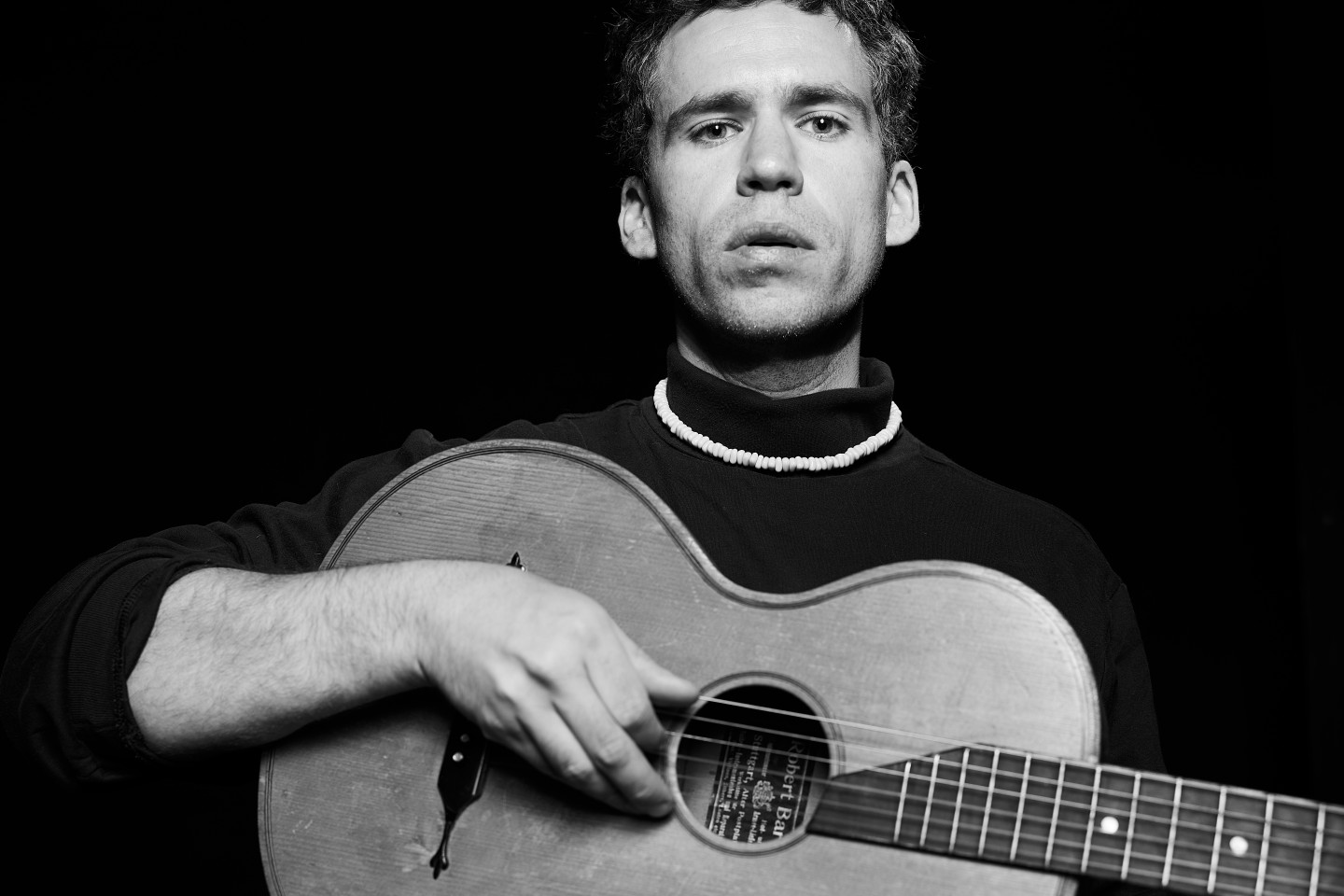

Vince McLellan

Vince McLellan

Andrew Savage has been making New York music since the moment he moved to his first Brooklyn apartment. Born and raised in Denton, Texas, home to the University of Texas’ School of Music — and, by extension, a vital independent music scene — Savage had already made smart indie rock records, fronting Teenage Cool Kids and making more left-field post punk as one half of Fergus & Geronimo before going out east. But Parquet Courts would be different. In a conversation with Interview Magazine in 2012, he said, “We knew that we were going to be a New York band from the beginning.” You can hear it in the metronomic churn of “Stoned and Starving,” the anxious polemic inside “NYC Observation,” and the slick bounce of “Walking at a Downtown Pace,” tracks spread out across a decade but united by their fascination with the city.

Savage’s second solo album, Several Songs About Fire, is something new. He’s left New York. He’s itinerant at the moment because there’s a tour coming up, but he’s settling in Paris. And though he hadn’t made the choice to relocate when he sat down to write this record, his reasons for leaving aren’t too hard to parse. After more than a decade in the same apartment, in the same city, in the same country, trying to get by as a musician and a painter, Savage wanted a life more conducive to survival and, maybe, even more than that. That’s why he insists that this, like all his albums, is ultimately hopeful — delicate and melancholic in some places, utopian and playful in others, poetic and affecting throughout. A few days ago, I called Savage, who was in London, a couple of hours away from the west of England, where he recorded Several Songs About Fire, to talk about leaving New York and learning to live alone.

Vince McClelland

Vince McClelland

The following Q&A is the full transcript of The FADER Interview’s latest episode, lightly edited for clarity. Find the new episode and The FADER Interview’s full archive at this link, embedded below, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

The FADER: So when did you leave New York to go to Paris?

Andrew Savage: That would’ve been in May.

I realize that, in some sense, the album is a longform answer to this question, but why?

Why did I leave the US? That’s an answer that would take even longer than an album, I think. But I guess, in a nutshell, healthcare would be a big reason — having access to it, which you just don’t in the States unless you have money. I completely ideologically disagree with that, and I just think it’s so completely wrong in so many ways. Even compared to other western democracies, which are becoming increasingly beholden to corporate interests, no one is quite as beholden to corporate interests in the way the American government is, and that comes out in some really uncomfortable ways, and one of those ways is access to healthcare. Another one of those ways is how we have massive gun violence because there’s an industry with massive government influence that keeps money flowing into it. And it’s the same; the medical industry and the gun industry are very similar in that regard.

And we’re also, even though he’s not president now, still very much living in the Trump era. Trumpism is Pandora’s box that has been opened. So there’s a lot of reasons: There’s climate reasons as well, and there’s general health reasons. I thought it might be a good thing to get residency in the EU somewhere, and Paris made sense as a place to start because that’s where I have the most friends in Europe and the record label has an office there, so there’s some support there, and it’s pretty easy to get around the world from Paris, so there’s a logical thing to it. It’s a charming city, but I’m not really a full-on Paris nut. Really, I don’t live anywhere right now. I don’t have an apartment anywhere. I’m about to go on tour, so a lot of my stuff is at a friend’s lockup in Paris. The other half of my stuff is at a lockup still in New York. I’m living pretty itinerantly.

You certainly wouldn’t be the first American artist to decamp for Paris specifically. You’re in a good lineage there.

I wouldn’t be the first one, and people are really tempted to make that comparison and continue that narrative. And I understand why it is tempting. I don’t know if I’m going to stay in Paris. I mean, I’ve got options. And that’s the point really; I don’t want to be associated with a place. I’ve been associated with New York for so long, and everything that’s been written about me and Parquet Courts is having to do with us being a New York band. But I guess the point is right now that I don’t really live anywhere and I’m not of any place right now. I have made the emotional and ideological decision to leave the US, that’s for sure.

I always find it interesting that Parquet Courts were spoken of or written about that way. Obviously you actively engaged with New York in a lot of your music, but it seemed quite clear that you were also sort of a transplant band, that you were from Texas. I listened to Teenage Cool Kids before Parquet Courts happened. That was what I knew you from originally, and Fergus & Geronimo and stuff like that. It seemed like the experience you were writing about in New York was very much from that of somebody who’d come to the city later on.

I guess. That always bothered me a bit because… I don’t know, The band started in New York and three of us were from Texas, but I’m proud to say that we were a New York band, and I’m still proud to this day to call myself a New Yorker. I left Texas for a reason, and that was to wash the Texas off of me. But one thing I’ve learned is that if you’re from Texas, people will remind you for the rest of your life, whether you like it or not. People always want you to be from there first, and they always want to remind you that you’re from there. It’s almost like, “No, you’re not good enough to be called a New Yorker. You’re still a Texan.”

Nobody calls the Talking Heads a Rhode Island band, even though that’s where they started. They started in Providence at RISD. Nobody points out how Thurston Moore is from Connecticut, Kim Gordon’s from Los Angeles; Sonic Youth will always be a New York band for people. But people do love to remind me that I’m from Texas and that I’m a transplant, as if most people in the arts community in New York aren’t. So yeah, I’m from Texas, for sure. I haven’t lived there in a long time and I’ve certainly lived in New York longer than I’ve lived in any place, but for some people I will always be a Texan, and I guess that’s fine. And some people are going to want to say that I’m a Parisian now just because it’s gotten out that that’s where I’ve been living. But the point is I just don’t want any of this right now. I just want to be me.

The implication of New York that comes through very clearly on the record and that Parquet Courts have been writing about increasingly on the last few albums, is the economics of living there, beyond healthcare — that just it’s a city that has changed so rapidly and it’s became almost impossible to be an artist. Had that always seemed impossible to you? Do you think it was you that changed over the last 12 or 13 years in regards to that, or do you think it was New York that changed and became more inhospitable?

Certainly both, and I can talk about both those things. I was kind of a lucky person that lived in one apartment for a long time. It was more protected, which doesn’t mean the rent was frozen. It wasn’t frozen, but it didn’t go up by much in those 12 years. Meanwhile, in the city around that apartment, it went up astronomically. That was a rude awakening. Whenever I was like, “Well, if I move out of here, I’m going to have to get another apartment somewhere, and looking at the prices of rentals and just saying, “Oh my God, how does anybody afford to live there?” I felt so naive when I realized what it costs to live in that city and what a good situation I had.

But it was one of those situations where there were holes in the floor, sometimes there would be no heat. The landlord didn’t want to help me an inch because they really would’ve rather me just moved out so they could charge market value for the place. It’s a different city than the one I moved to, that’s for sure. And one of the things I’ve always said about New York is you can’t expect it not to change, and you can’t expect it to be your version of it. It is going to move on without you, and that’s just what it is. It’s always changing, so it really makes no sense to romanticize it too much because if you are always trying to reference a certain era of New York and say, “Well, it’s not like that anymore,” you’re missing the point.

Having said that, it was a different city when I moved to it. There was more access to art for young people when I moved to it, and that’s just less of a thing now. I’m not indicting the city for that, and I’m not trying to complain. It’s just a statement of fact. When I moved there, within just a half a mile radius, there were 15 different DIY art spaces that were this really cool community. It’s always been expensive, but this is before it was so expensive that it prohibited that sort of thing, which is the state it’s in now.

I was talking to a younger friend of mine and bemoaning, “Why doesn’t somebody of your age start another DIY space like this?” And he was like, “Well, I mean… You need a bigger space to do that sort of thing. And people my age can’t put down three months rent at one time in a space like that.” And I said, “Fair enough.” It’s so tough the way that financially the city has changed. It’s just tough on people. But on the other hand, it’s an extraordinarily exciting place because it does attract a lot of creative people. But living a really bohemian life, which was my attraction to it originally, is much more difficult to do there. I’m interested in finding a place where I can do that. I don’t know where that is yet.

I still consider [New York] a huge part of my identity. And when people ask me where I’m from, that’s what I say — “I’m from New York” — because that’s where I became who I am.

In New York, I always felt like I was attached to a chord that was just pulling me through a city.

The bohemian life seems so intertwined with the starving artist idea. I hope I’m not quoting you out of turn here, but when you talk about the suffering myth, it seems to be hinting at something like this. My mom does it with me all the time: “If you were able to pay rent, Alex, would you really be an artist?” It’s like, actually, it would be really nice if I could eat well. Were those things always intertwined for you?

I guess to be an artist is this inclination to make your art by any means necessary. You don’t start making art once you’re comfortable. It’s just this thing that you have to do and you have to get out of you. For me, that definitely remains the case. I’ve realized that’s the point of my life: to make art. That’s above anything else — above ever, say, owning a home or owning a car. The most important thing to me is to make art by any means necessary. And that was the attitude for a long time in New York. That’s still a lot of people’s attitude there. But if I paid significantly less rent somewhere, then I could probably spend more time making it or have more room to make it.

I know you’ve only spent a very short amount of time in Paris having come from New York, you have this slightly more itinerant way of living just for the time being, and you’ve made a lot of this record and recorded it in the U.K, in the west of England. How has that routine changed the way that you work? How sensitive are you to the life that you live day to day influencing your art?

Well, I can talk about living in France for the past few months, and time moves differently. I feel like I have a bit more of it, which is nice. In New York, I always felt like I was attached to a chord that was just pulling me through a city. And that also influenced my personality. I’m always, always moving. No one describes me as chill. But living in France over the past few months, I felt like time moved a bit more slowly. I kept to myself a bit more. I’m not fluent in the language, I’m learning. I’m doing alright, but sometimes I’d rather just stay in and work on something than go out and have to have a conversation with somebody.

So I found more time to be alone, and I’ve gotten a lot done in the past few months. So far it’s been great, but I need to really build a new life. I need to build a studio. I need to set myself up so I can get into the routine of creation that I was in the States. And that hasn’t happened yet, and [Paris] probably won’t really feel like home until that does happen.

I’ve read somewhere that this is your first time living alone. Is that true?

Yeah. I’ve lived with roommates my whole life.

Has that changed your artistic process?

Really, all I’ve done is rent apartments for a few months at a time. I turned those places into small makeshift studios, which was nice because I could work whenever I wanted to, though these are apartments, not studio spaces, so I’m not painting in there, but I was doing a lot of drawing. But, like I said, it’s really hard to compare the two [cities] yet because I feel like I still really haven’t gotten fully set up over here.

There’s a particular idyll that you describe in “Riding Cobbles” on this record. Is it too simplistic of me to think that that’s aspirational?

No, no. It kind of is. I mean, it’s a very whimsical song. It’s like a daydream. It’s supposed to be a bit naive and dreamy — the hopeful dream, like an outsider looking to get in somewhere.

Kathleen Alcott wrote the introduction the bio for this record. You had an excellent conversation with her a few weeks ago for Interview Magazine. She expressed really well something that I’d been struggling to pinpoint, which was this distinction between antiquity and what you end up calling hyper-nowness in your music. Are there artists from any genre, first of all, who you think express that nowness really well? Where have you drawn that particular influence from?

I mean, hip-hop does a great job of that, doesn’t it? Because, by its very nature, it’s a commentary on what is happening now and what culture is now. And for that reason, it is a bit disposable. I don’t mean that in a bad way. I mean that in a way where eventually in the genre, it gets replaced by the next track, and it’s not one that really tries to clinging to the past. It doesn’t try to romanticize because it’s always about now. So there’s always references to… I mean, at this point, it’s an older song, but “Hotline Bling,” it’s about texting. And it’s completely relatable for that reason, because most people text.

I think when you try to avoid stuff like that and the realities of life, you risk becoming twee or pastiche or something, and I really have no interest in that. With rock or folk or country, those are genres that are always a bit tethered to their past. No matter how far they travel away from it, there’s still a line directly connecting them to the origin point. They’re genres that work within a tradition.

For that reason, I think it’s interesting: You can talk about nowness, about modern life, and still be of that tradition. And I guess that’s what I want to do. I think that when you’re an artist, what you’re doing, everything you do is a time capsule for the day that you wrote that song or painting or photograph or whatever you want to express… because people are going to be listening to it in posterity. People are going to be looking back on it. And you want to be able to give them a sense of what that day in your life was like, what that time was like.

That’s one of the things that we, as humans, as an audience, find so captivating about art, and why we’re still attracted to art that surrounds events in history. Earlier, I talked about something being post-war. We’re still interested in framing things like that because art is basically is a time machine. It is a portal back into that time, and it helps us understand history, and it helps us understand life.

When people listen to my music, I would like for them to be able to get the chance to travel back into 2023 at some point in the future and get an impression of what life was like. Speaking of romanticizing New York, that’s why we still love the Velvet Underground and the New York Dolls and the Ramones: because they take us to the ’70s in New York.

I’ve always been interested in this word as a writer, but the word “timeless” seems to me like it’s an odd compliment, maybe even a backhanded one.

Yeah, maybe.

Years ago, there was a review of about Exile on Main St. for an anniversary, I assume the 50th — and they were saying, “People will call this album timeless, but it’s absolutely not timeless.” It sounds like exactly the time in which it was made and exactly the point in these people’s lives in which it was made.

That’s such a storied part of the Stones history that, yeah, when I listen to Exile on Main St., I’m daydreaming of them in a French villa, avoiding the tax man. It’s not quite timeless — it is of a time. But that’s the point, isn’t it?

“We’ve been telling the same old stories for a long time with the same kind of pieces. It’s the perspective that changes.”

It sounds to me like you find yourself intentionally writing for a listener in the future, to an extent. Is that fair?

To an extent. I mean, I’m writing for people now. But as a fan of music, I’m cognizant that it lives on and that people will be listening in the future. But no, I’m not writing for people in the future. It doesn’t make any sense to avoid the now in your art, because then you’re making “timelessness” a goal, and that doesn’t really make sense.

And yet to draw these parallels between antiquity and the very modern, this hyper-nowness, you are, to some extent, trying to draw that line between the past and the present. You even comparing yourself to Joyce in Trieste, for example.

I guess so. Antiquity is… Those are tools of language that we have at our disposal. Language is a somewhat limited set of tools, and we’ve been using the symbolism of antiquity, well, since it wasn’t antiquity, since it was nowness. It’s a language. These are the shapes and sounds that we have to play with.

Most artists, whether they know it or not, use a vocabulary, a vernacular, and we pull them from everywhere. We’ve been telling the same old stories for a long time with the same kind of pieces. It’s the perspective that changes, and it’s the perspective that keeps things interesting. The history of art has been just a handful of the same stories told over and over again, but it’s the perspective and the way that you use that language and the way that you use those tools that you’re given that make it compelling.

You mentioned in that interview with Kathleen Alcott that these were songs you would leave behind in a fire, and I was curious about that line because it’s not really elaborated on. I was wondering why these wouldn’t be songs that you would carry with you. Why do these songs have to be destroyed in your head?

I think I said I’d leave them behind to save myself. In the situation of a fire, you do have to let some precious things burn, don’t you, in order to save yourself. The making of the record did feel like a last act of sorts, like there was a sense of urgency in my leaving. Yeah, I guess it can be summed down to that. It was the last thing I did as an American, and then I got out, with so much urgency that I didn’t bother to even take the last thing I did with me. That’s the way I see it.

There’s something about you recording this last American album in Bristol that feels quite poetic.

You’re not the first to remark on that. That really came down to… It’s a bit unromantic, but it was just quite a logistical thing. I wanted to work with John [Parish] because he’s incredible. At this point, he’s at a point in his career where he can just stay close to home because people come to him, and that’s just how it is. He’s a terrifically brilliant guy.

It seems like there was a routine, though, with making the record that was maybe to some extent what you had been searching for since leaving the States. He had to be out by seven o’clock every evening and you had to hit this pattern. Did you find that helpful creatively?

It was helpful because when he would leave I would. We were working quite full days. Everybody started early. And then, when he would leave, we would maybe all go to the pub, and then I would go back and just listen to mixes and edit. I’m a pretty staunch editor. I always come to a recording session with lyrics. I don’t understand people who write while they’re in the studio. That, to me, sounds way too hectic. Best to have it all ready when you’re there. But I do edit, so when he would leave, I’d go back and I edit. These days, every line in a song, I’ll tend to write it three or four times, just so I can find the core of what I’m trying to say and the best way to say it.

So there was a lot of that. And sometimes that would go late into the night, and then the next morning I’d be like, “Okay, I figured this vocal out. Let’s do it.” A lot of times the days would start with doing the vocal on the song we finished tracking the day before, and then I would spend the time in between really editing… And rehearsing, too, because you’ve got to figure out what you’re saying and you’ve got to figure out how you’re going to say it, and then you’ve got to figure out how you’re going to perform it.

Even aside from songwriting, [poetry] is a performance, which is I think one of the things that keeps it a bit maybe mysterious and intimidating for people. It’s meant to be read both by the author and by the audience. When you have a book of poetry, you’re meant to read it out loud. That’s how you find the meaning in it. It is an art form that is made for the voice. So I would spend a lot of time editing, and I would spend a lot of time figuring out the cadence and the syntax and how I was going to deliver these words. I’ve worked with other producers that work around the clock, and that can be cool because you can just keep going. But I think that the breaks for this record with John were important because they kind of helped me take those moments of quiet back in the place where we were staying to hone in on certain aspects of [the album].

I’m more or less really proud with, well, with the album writ large, but definitely with all of the lyrics that I committed to it. I think I chose the right ones. I think the song “Mountain Time” might be one of the most proudest lyrical moments on the record, or even in my career, because I really got all the words just so. They really land back at me.

“Mountain Time” really feels like a song about the end of a lot of things. It’s a quite autumnal track. There’s a lot more romance on this album ¸— and the end of a lot of romance — than I’ve seen written about.

I personally would not qualify it as a breakup record, because a breakup record is more something that’s dealing with the past. To me, it reads as an optimistic album. And I think it’s a lot about the future as well. I think it’s a hopeful album. It begins and ends with a sort of cautious and bittersweet type of hope. If you look at “Hurtin’ or Healed” and “Out of Focus,” they’re both a bit trepidatious, a bit melancholic, but hopeful too.

First songs and last songs are important, I think, because it’s important to benchmark some idea of what the album is about. That’s usually where I would start, if I were trying to figure out what any record is about: the first and last songs.

Did you know from the jump that “Out Of Focus” would be the last song?

I can’t remember if I knew that when I wrote it. I’m going to go ahead and say, no, I did not know that. But it probably became clear pretty quickly. A lot of times, I’ll ask for people’s opinion, insofar as the sequencing goes. So I asked John Parrish, I asked my manager James Oldham, I asked Jeanette Lee and Geoff Travis at Rough Trade, and I think everybody put that one as a good choice for last. At that point, I’d already pretty much made up my mind that it would be the last track too, so it seemed like a universal agreement.

So when you were writing, you knew that you were creating something hopeful. It wasn’t something where you looked at the lyrics sheet afterwards and went, “Oh wow, I’ve written something with some hope shot through it here.” You knew there was a sense of hope to this record.

I did. And, by and large, a lot of the stuff that I make has that quality to it. I’m not a terribly pessimistic guy. I mean, I do work with my own pessimism, and I think it helps in art to be at least mildly agitated about something. There’s got to be some sort of message. But I think that, by and large, I’m an optimist, and I would hope that that’s something that comes out in the art I make, even when it’s angry and bitter, which sometimes it can be. Bitterness, like anything, is a tool at your disposal; how much you use it is how much you let it define you. I use optimism and hope as the main ingredient on a lot of things that I do. There’s a continuity there.