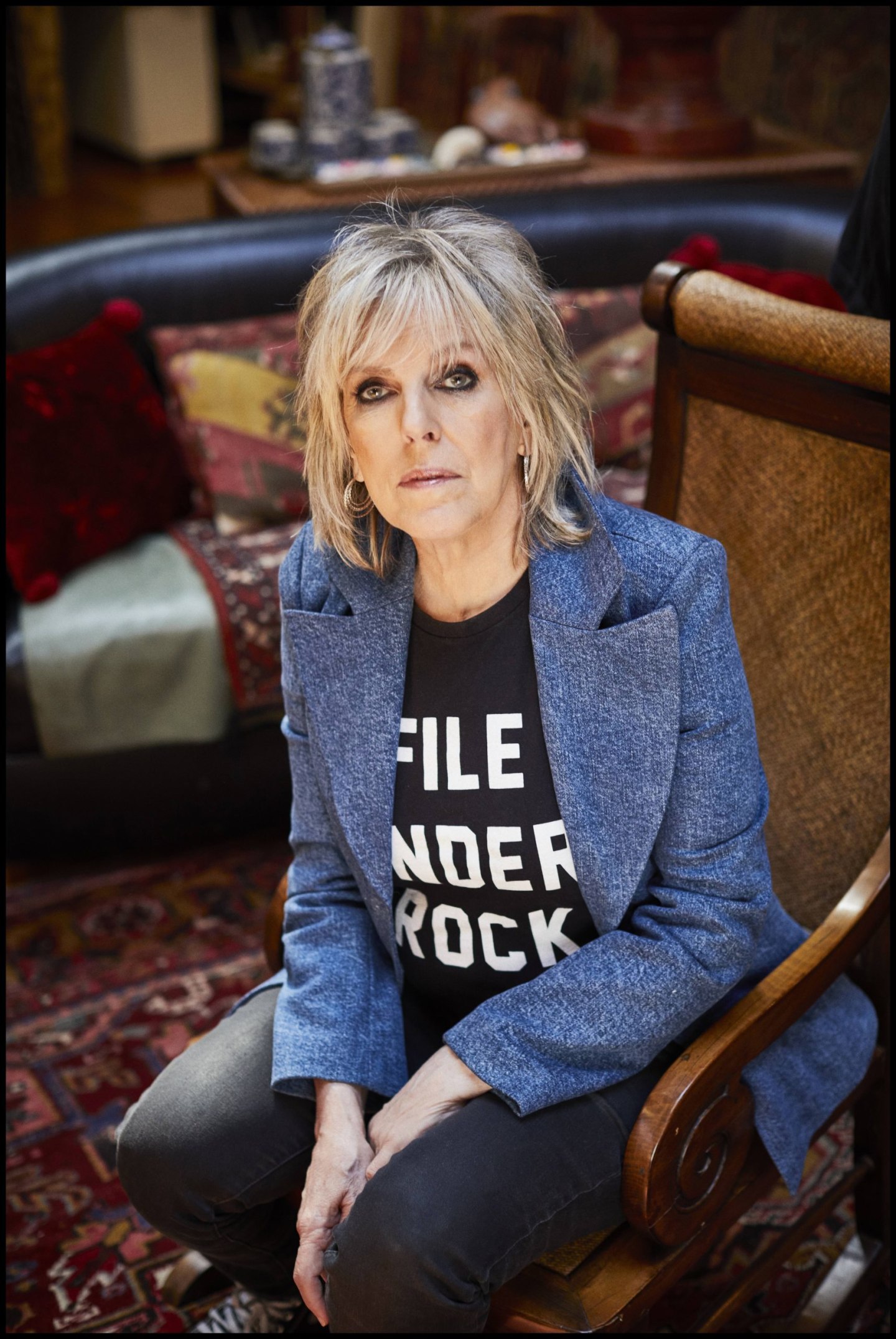

Lucinda Williams. Photo by Danny Clinch.

Lucinda Williams. Photo by Danny Clinch.

Lucinda Williams is a master of the art of the long game. A consummate disciple of American music, Williams has always operated under the assumption that when the craft comes first, the rest will follow — a rare quality in an industry that measures success by the numbers. She made redundant the question of what exactly her music was to others; her main concern was to free her songs to take on lives of their own.

The slow build-up of her early career finally resulted in widespread acclaim with the release of her 1998 Grammy-winning record, Car Wheels on A Gravel Road. A fanbase already stacked with critics and celebrated singer-songwriters finally burst open its doors to the outside world. To this day, Car Wheels remains Williams’s best known album. But her musical evolution remained as unaffected by external pressures after her breakthrough as it was before: From that record’s much-anticipated 2001 follow-up, Essence, to her latest release, Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart, every one of her creations is rooted in her present moment. Not for love, money, or domineering record executives has Lucinda Williams ever tried to sound like anyone other than herself.

While her legions of die-hard fans may respect her unflagging integrity, it takes more than that to earn the kind of obsessive devotion she has inspired since the release of her first album in 1979. If she occasionally comes across as overprotective, those who love her understand it is because she is carrying precious cargo. From her inimitable drawl to the delicately fashioned lyrics that are by turns wry and blisteringly sincere, every aspect of her music feels like an encounter with the truth, drawn from a life lived close to the bone and free of restraint.

When I interviewed Williams, it was with a sharp mind and generous spirit that she reflected on what it takes to dedicate your life to music, her one true religion.

Danny Clinch

Danny Clinch

This Q&A is taken from the latest episode of The FADER Interview podcast. To hear this week’s show in full, and to access the podcast’s archive, click here.

The FADER: Hey, Lucinda Williams! How’s your tour going so far?

Lucinda Williams: It’s been going great.

Any standout moments so far?

The main one would be the fact that I’m even touring since my stroke. I didn’t even know if I was gonna be able to stand up on stage or if I’d have to sit down. I haven’t had to sit down. I’m not playing guitar, though. That’s the big difference. It was hard at first, but now I’m getting used to singing without playing, which is kind of fun in and of itself. It frees you up a little bit more.

There’s so much geographical specificity in your lyrics. I think about Sylvia leaving Beaumont, Texas in “The Night’s Too Long,” coming home to that house on Beaumont Avenue in “Bus to Baton Rouge” on Stories from a Rock and Roll Heart. How would you describe the relationship between your music and place?

I guess I started doing that to add color to the songs, because I think it’s more interesting if you name a town so people can relate to it better. Also, the names of the towns are so great, like Vicksburg and Slidell. There’s a kind of musicality to them. I’m still writing songs the same way, and I like to think I’m always growing and developing and getting better. I certainly haven’t changed my point of view about things. The style of music I like is the same. I still don’t like contemporary country music.

Why not?

I just don’t like the production. I don’t feel like the songs are as good as they used to be. There are a couple of contemporary country songs out right now that a friend of mine introduced me to that I thought were really good. What’s interesting is that the theme in both of them is, “What happened to country?” So I do open up my mind and I listen to see what’s going on.

“Im still writing songs the same way, and I like to think I’m always growing and developing and getting better. I certainly haven’t changed my point of view about things.”

Your lyrics are really some of the best I know. What’s the process?

Usually, the first part of the idea is what I call stream of consciousness. Stuff comes out and you just write it down. You’re not trying to make everything rhyme yet. After that, I’ll go through and organize it into verses and a refrain, and make sure the rhyme scheme is good, and think of the melody. Once I get the melody, then I need to go back in and make the lyrics fit.

Would you say the process has stayed consistent throughout your career, or is it evolving?

It’s been pretty consistent, except now I’m more confident about getting whatever comes out first down on paper, not worrying so much right away about it being perfect because that’ll come later. The song will evolve as time goes on.

I feel like you have a real trust in and spiritual connection to music.

Thank you for recognizing that. Even at an older age, I’m still very idealistic and passionate about what I do.

On the new album, I love the line, "The errand of the fool has carried me this far to the place where the song can find me."

I have to credit my husband with that, Tom Overby. He's my manager and my husband. We’ve started collaborating on songs.

How has that been?

It's going great. I never thought it would be possible, but it just happened organically. We started doing it on the last album, and it just happened gradually and by itself. We didn't sit down and say, "Let's write a song together." It was more like I’d be working on something and — he was kind of shy about it at first — he'd say, "I've got these lines here and you might wanna look at them and maybe you can use them in something or whatever. You don't have to, I just wanted to show them to you." And I’d take them and look at them, and they were good.

He kept it secret for a while, but it turns out he’d really been into creative writing when he was in college. He ended up becoming a record company guy, which is ironic. One time, I got mad at him because he was supposed to meet me somewhere and he didn't show up, and I said, "Fucking record company guy." I hung up the phone, like, "Wow, I'm dating the enemy." But it ended up being great. We ended up becoming really good friends and lovers.

I’m a little curious about “New York Comeback.” Are you referring to something specific, or is that a social commentary?

It’s just a metaphor for a comeback. There’ve been universal comebacks, and then my personal comeback from my stroke. New York City had a comeback after 9/11. The whole country had to come back after the pandemic. Nashville had to come back after a tornado that happened around the same time as my stroke. It’s almost biblical: the pandemic, a tornado, my stroke, all around the same time.

Is there a guiding theme on this album, something that’s been particularly on your mind? I imagine the stroke is at the forefront.

There’s a thread of surviving, that uphill battle, strength, perseverance, coming back.

“They wanna get your songs on the radio and figure out the rest of it later. I happened to have some success in spite of not sounding commercial, which is hard to do.”

“Never Gonna Fade Away” is as good a summary of your artistic ethos as any. It reminds me of the way I see your career. You’ve managed to avoid the pitfalls of the easy-come, easy-go success. What do you think is the key to your staying power?

Because I’m stubborn. The blues guys used to say, “I’m too mean to die.” Well, I’ve just seen too much of it in the music world. That’s what “Real Live Bleeding Fingers And Broken Guitar Strings” is about, the tendency of the rockstar. And I wrote a song called “Little Rock Star” that talks about that self-destructive thing.

Do you think the desire for fame is part of that?

I don’t know what’s going on in their heads. Maybe they just think on some level, subconsciously, that self-destructiveness goes along with being famous. Or maybe they’re self-destructive first and somehow manage to get famous regardless of their self-destructive tendencies. Eventually it catches up with them. It’s hard to say.

Were you concerned with getting famous in the beginning of your career?

I wanted to be successful to a certain degree. But I was also soaking it all in and taking things a step at a time. I definitely didn’t want to get famous at the risk of sabotaging my music. I remember being really afraid of that because I’d seen it happen before: Really talented artists would make an album, and I’d be like, “Why did they do this?” It’d be overproduced, trying to get on the radio. I was deathly afraid of that.

I was like, “I will not be overproduced. I will not let anybody do that to my music.” That made it harder to get a record deal because, of course, that’s what they want to do. They wanna get your songs on the radio and figure out the rest of it later. I happened to have some success in spite of not sounding commercial, which is hard to do. I think that’s just going out and playing live as much as I could everywhere. That’s all I did. That’s still the best way to do it, I think.

Car Wheels on a Gravel Road had a very specific sound, and then you took a new direction on Essence. It’s a pleasure to watch you evolve. Is there a conscious sense of the way that your relationship to sound changes, or is it all instinctual?

I was conscious of the fact that Car Wheels made such a statement and did so well. I was kind of terrified going into the next record after, because it’s got to be at least as good or better, but I think I did that. For a while, Essence fell in the background and wasn’t talked about as much as Car Wheels. But over time, people started coming up to me saying Essence was their favorite album.

I like thinking about you and your husband writing songs together in your apartment. Are there any other collaborations that stand out to you? You’ve worked with such an incredible roster of musicians over the years.

I haven’t really been successful at co-writing up until now. I’ve gotten together with people to try to do that, but it’s gotta be the right person. A lot of people thought — and I thought this too — that if you put two really good songwriters together, they’re gonna write this massively amazing song, but it doesn’t always work that way. I got together with John Prine to try to write. We went and had dinner and drank a bunch of wine, and then we went to the Bluebird and ordered another bottle of wine, and you can see what’s coming: As the night wore on, we just drank more and we didn’t really get anything done, but we had a great time.

There’s actually a new song about that. I did a memorial tribute concert to John Prine at the Ryman not too long ago, and everybody did a John Prine song. I performed that song, which I actually wrote with Tom and Travis Stevens, tour manager. He’s a singer-songwriter, quite good, and I wasn’t able to play — that’s one reason I veered into this collaboration thing. Travis would play, then I would add some more lyrics or Tom would or Travis would about getting together with John Prine and trying to write a song. It’s called “What Could Go Wrong,” and everybody loved it because it sounds like a John Prine song, kind of.

Would you say your more successful collaborations have been less writing, more musical, like Steve Earle or Emmylou Harris?

Yeah, singing on their albums. But Steve and I have been talking about trying to write some stuff together. We have a kinship that way. Steve Earle is the yin to my yang. We’re the male and female outlaws in Nashville.

Danny Clinch

Danny Clinch

How do you feel your relationship to country is affected by living in Nashville? Do you feel surrounded by it?

You can be, but you don’t have to be. If you listen to a certain radio station, you’ll hear it all day long. But I’m trying to soften my view about it a bit and not be so angry.

It’s hard! You naturally want to have an artistic community where you’re feeding and pushing each other.

There definitely is that here; it’s just underground. It helps me also, when I’m feeling frustrated about that kind of thing, to pull out my Bob Dylan and Neil Young albums, because they’ve followed the right path.

What’s hard about that conversation is that it can seem judgmental, and I don’t think it is. There are so many ways to choose a career. Did you experience hostility for trying to do something different at the beginning of your career, when everyone was trying to put you in a mold?

Most of that stuff was happening inside the offices of record companies, so nobody knew about it. When I made the self-titled Rough Trade album, the label wanted a single, and before they put that out, they sent it to this guy in New York City to remix it for the radio. We got the remix back, and the record label guy calls me up and says, “Hey, come over and listen to it!” So I went over to his office and he’s jumping up and down in his Gucci shoes going, “Isn’t this great? It sounds like a real record now!” The fact is, I hated it. I thought it sucked. The bass and drums were pushed way up front. The vocal was pushed back. It sounded horrible, I thought. That was the beginning of the struggle with the record label thing.

There’s something encouraging about that tension, though, because it speaks to the power of art. When businessmen are anxious about something they can’t quite hold, it means you have something subversive. That’s “the glory… over the fame.” How would you define the glory?

The glory to me is being successful and living on your art, having your art support you and being admired by your peers and all the emotional satisfaction that comes from it. And being able to quit your day job. That always helps.