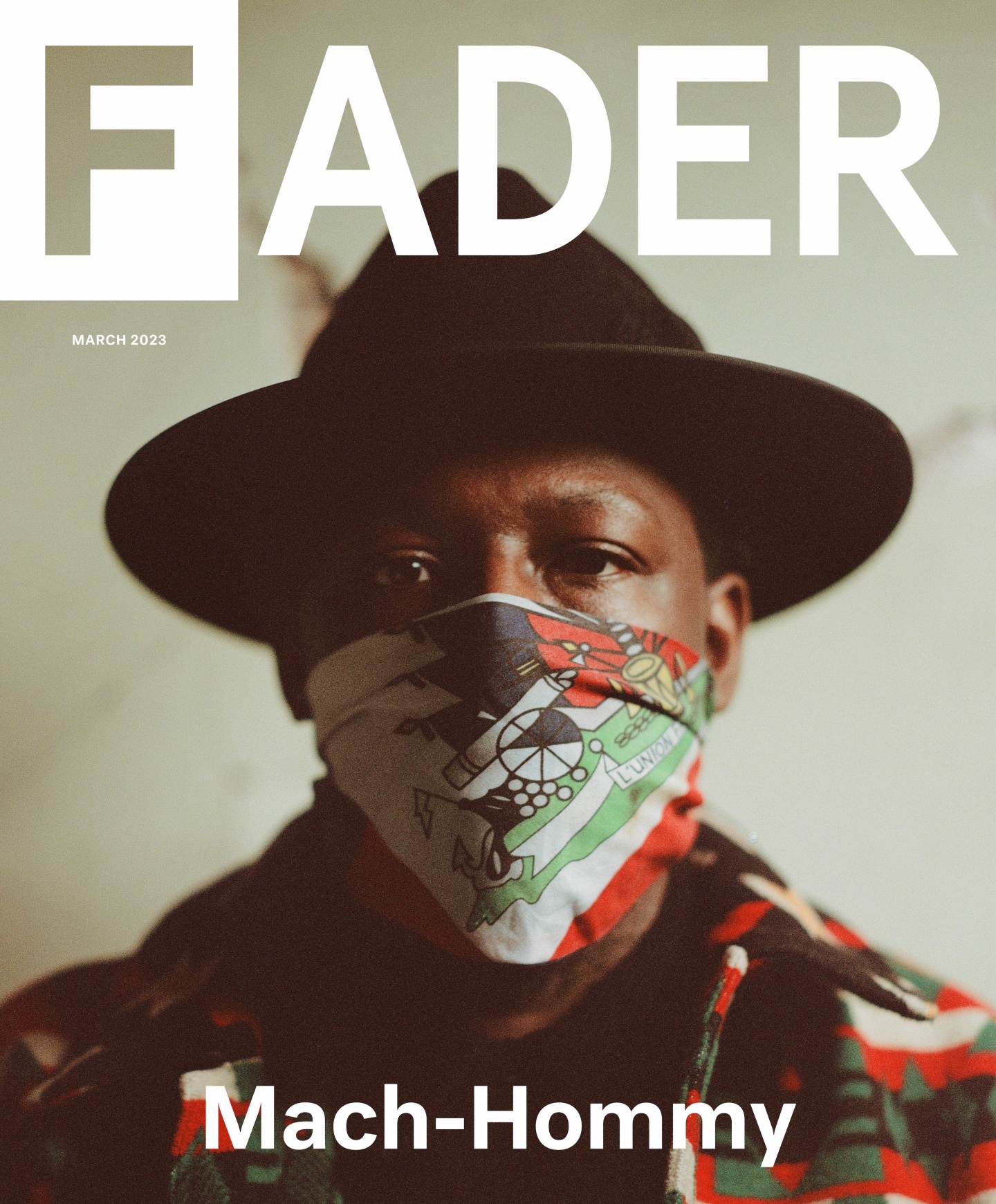

Order a poster of this Mach Hommy cover on The FADER's web store.

On a Sunday afternoon in late January, Mach and I meet at a restaurant near my office in the middle of Hollywood. This place, he explains, is near the farmer’s market he frequents, and he suspects the head chef has been the one beating him to certain choice pieces of produce. Mach speaks about food with the seriousness that he does music — the tragedy of an overdressed salad is not calories, fat, or sodium, but the fucking up of a delicate creative balance.

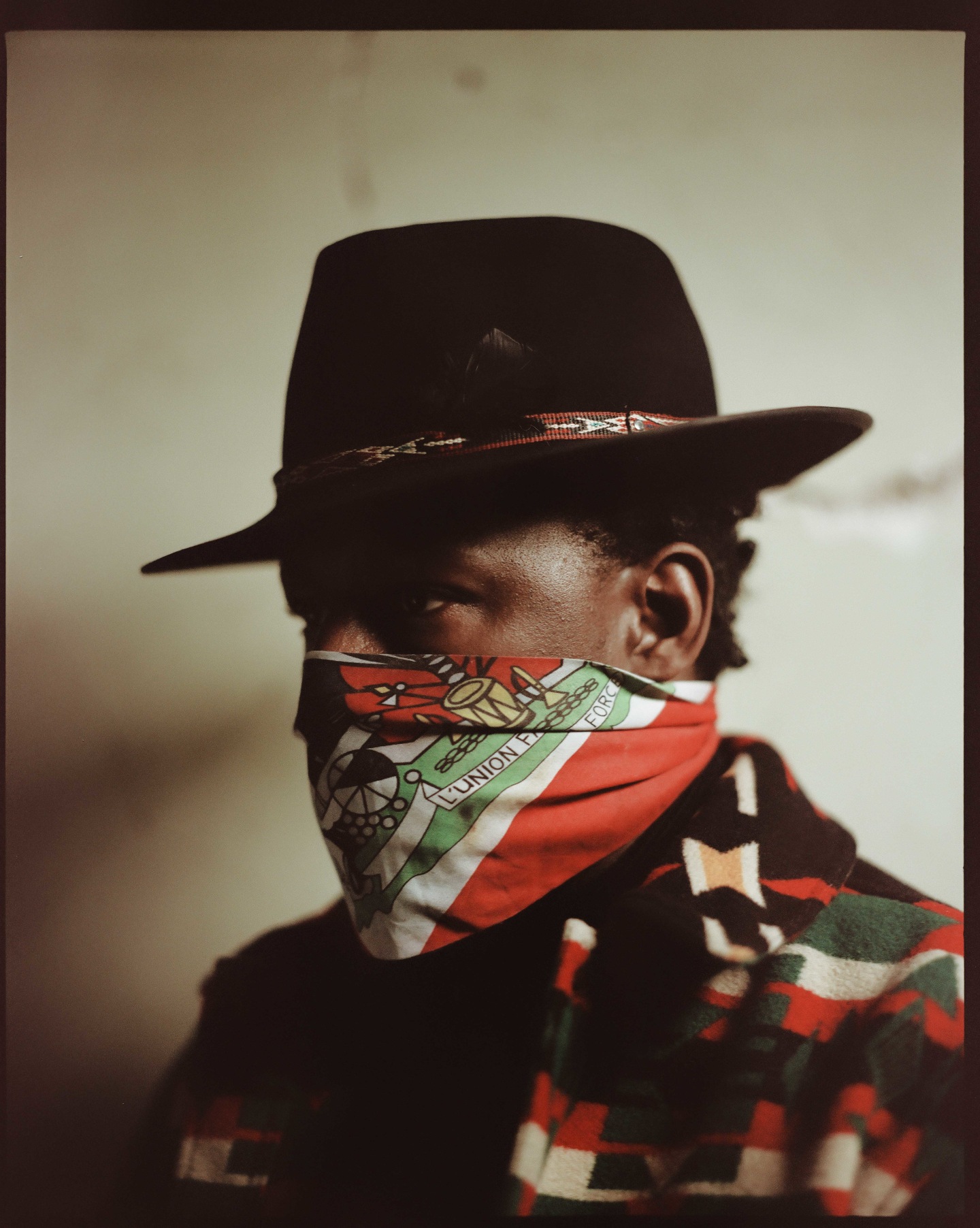

Our table, on the restaurant’s roof, looks out on a horizon that’s fitting for Mach’s preoccupations today: the Hollywood sign next to the Church of Scientology and the instantly recognizable Capitol Records Building. Though there are long tangents on which DJs could secure the best Queens rap B-sides at the turn of the century and what actually goes on inside high-level marketing meetings, the spine of the conversation is business — how it threatens to swallow artists alive, how it forces them to bifurcate their brains. He’s unmasked, of course; though he has no plans to appear this way in public any time soon, he thinks his appearance proves something about his durability. “What I’ve been through is not written on my face,” he says.

The second formative recording experience Mach has chosen to revisit is one that pointed him on the trajectory that would make him a breakout star in hip-hop’s underground. He also speaks for the first time publicly about the extent of his interest in film, the medium that brought him, in however roundabout a way, back to rapping.

It was my third or fourth trip to Buffalo. We were in Tommy Pretzel’s apartment, myself, Conway, Wes, Way Russian homeboy, Chef Dred, Cutter, and Monk may have been there too.

I hear a lot of misinformation floating around, so let me set the record straight. The only reason I was there was because I had some fire-ass camera equipment that I wanted to test out, and Wes had complained to me that no one was willing to bring a good camera out to where he was from. I’ve always had an innate curiosity for filmmaking, and, more specifically, biographical documentation, so he seemed a worthy subject to me. There are people who behave today as if they was with the shits back then, but I was there when niggas had nothing interesting to offer anyone, nothing but potential.

I’m sitting there at the kitchen table, organizing my documentary footage, and that boy Tommy Pickles puts a little loop on. I think that’s what they were calling him at the time: Pickles, Pretzels, and Pepperonis. He had the most absurd nicknames back then. Anyway, he puts a beat on and Conway is like, “Yo! Beloved, you gotta jump on this,” and I’m looking at him like he’s crazy. I decided to brush it off, but he doubled down, “I know you nice, my nigga; so-and-so let me hear it, bro! I need that god jew(els)!”

Up until that point, I had presented myself as the man behind the lens, and no one ever even came close to suggesting anything to the contrary. I hadn’t recorded a peep, much less a verse, in almost three years at that time. Mind you, I got no album out, no social media traction, no nothing. I’m just me, nahmean. But niggas was already convinced. If you know anything about me, you know that I stood on my square regardless. I was on my, “I don’t really know what you’re talking about bro.” I was flat out denying that shit.

On Day Two, Wes jumps into the fray telling me how so-and-so let him hear some exclusive butters. Same as with Way, I’m flat out denying the whole thing off rip, but I’m also starting to warm up to the idea a little because, for one reason or another, something made me say, “I don’t do that shit no more.” Niggas persisted, “Mach, you’re too great to ignore this gift, it’s a gift from God,” or “I know you into film but you buggin’, Lord.”

Boom, it got pretty heavy after a while because even Chef Dred pulled me to the side one time on some, “I ain’t know you was like that, like that. You nice, Sun!” It was genuine … for the culture. Art for the sake of art (ars gratia artis). We were onto something.

Daringer took a turn next, same tune, he says to me, “I’ve heard a million raps but never anything quite like yours. Alc told me the other day … he thinks that you’re one of the greatest of all time. He plays your music everyday … he’s really a fan!” To which, my reply was total indifference. Wtf do you say to that kind of info? “What kind of game is this? Is niggas trying to gas me?” And if so, then to what avail? That’s what you have to tell yourself, especially coming from the Vailsburg section of Newark. Too much positive reinforcement, or what Diasporic Haitians call “speed,” means something bad is about to happen. It’s just the skeptic in me.

I’m mad af I can’t remember his name, but there was one more person who petitioned me for the verse. It was one of Wes’s cousins. We used to chop it up every time I paid a visit and that was my dawg. When it dawned on me, you know what was going on, and that he was checking for the shit as well, that really struck a chord. You know what I mean? He wasn’t even on no music shit but he knew something was about to happen. His intuition was on fire that time. He’s the one that ended up tipping the scales in niggas’ favor. If he hadn’t have stepped in — who knows.

Later that night, I would end up recording the feature. Back then, they were recording one by one, maybe two a day, but mostly one at a time. All day, Tommy would play the same one or two beats, as people flowed in and out of the apartment. By the end of the day, from around 10 p.m. to 1 a.m., you would end up with one or maybe two records, three if you was extra lucky, but that was rare, like good ribeye. I think it was around midnight when I decided to let mine rip. I told that boy Tommy to give me two tracks and the rest is history. They wound up naming the track “Beloved,” and that’s how it happened. It’s definitely been heard around the world more than a few times by now. Funny how time flies, but when I look back, I can confidently say that it was a good investment - the verse. Over half a decade has transpired since that studio session and look where we are. Look where I am. Mad ting.

The FADER: Why had you stopped recording? Was there any idle writing during this period? Was it a decision made with any sadness — and did you still have hopes of feeling creatively fulfilled?

Mach-Hommy: I stopped recording because of how unhealthy the process had become.

Some of the more basic interactions were becoming untenable: differences of opinion, lack of basic trust, potential for serious loss … fun times.

Back then, I had never done home recording. I was still going to people’s studios, which is a fucking major limitation within itself. You have to be given a wide berth when you’re coming how I was coming, you know, with a particular type of message.

Once the ecosystem fails you enough, once the seeds stop growing, that’s pretty much it. The fruit of your imagination has to resonate with others; or else, they can project their insecurities onto you, thereby removing all of the runway that was available prior to their initial act of dismissal. I needed a little bit of latitude if I was ever going to land safely. Sometimes a person’s mind is so narrow that there’s just no room left for anything that vaguely resembles different. It’s more than hard feelings: it’s more like a creative desertification. Unless you’re purposely aiming to dampen niggas spirits, why be so rigid?

When Burning Spear asked, “Do you know that social living is the best?” He also made sure to mention that it takes “lots of behavior to get along.” Y’all don’t feel me. The thing is this: it was never supposed to be like a job. Soon as it started to feel like that … I was AUDI RS 7!

How was your interest in film shaped? Which films or directors have been most formative for you, especially for your interest in documentary?

My first love is writing, and although there is writing in almost everything, film is my favorite medium of expression because it is inclusive of music, but music itself does not necessarily include spoken words, or live action. Make sense?

I don’t necessarily know the how exactly but I think I know the who. There were certain ones that stood out for me, that still stand out to me, ones like: Jacopetti & Prosperi, Jarmusch, Jodorofsky, Singleton, Spike, McQueen, Fuqua, Gray, Melvin Van Peebles, Gordon Parks, Sydney Poitier, Paul Thomas Anderson, Micheal Mann, Zack Snyder, Jane Campion, Chantal Akerman, Naomi Kawase, Regina King, Ava DuVernay, etc.

“Greatness is mined, that shit ain’t never on the surface.”

My interest in documentary begins on the inside, in the space where certain people’s stories are not being shown in the proper light, with the proper context and tone. Most of this (current) shit is lacking in basic dignity. Not the stories themselves, but the storytellers’ conscious failure to capture any of it. They’re fucking lazy.

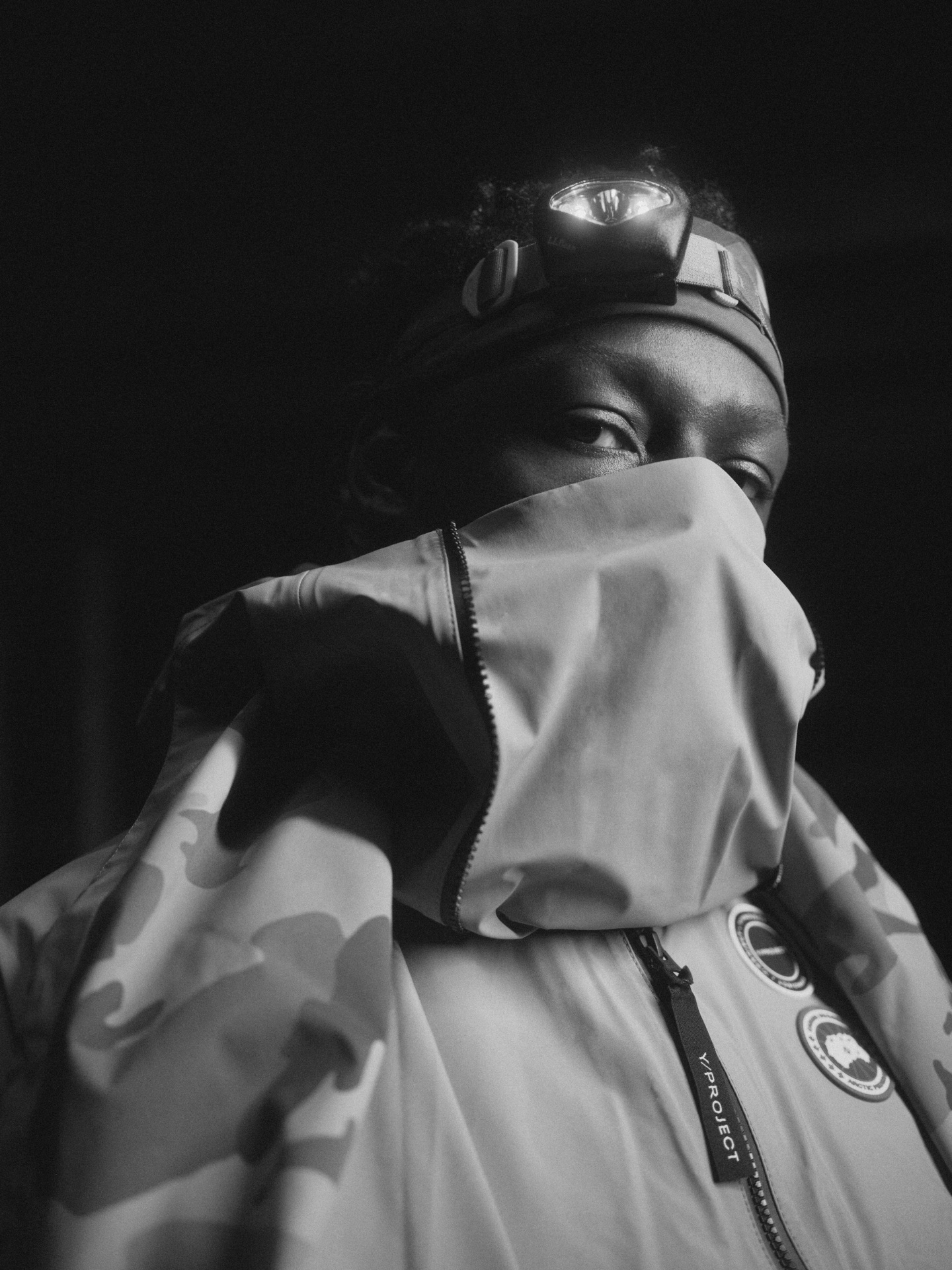

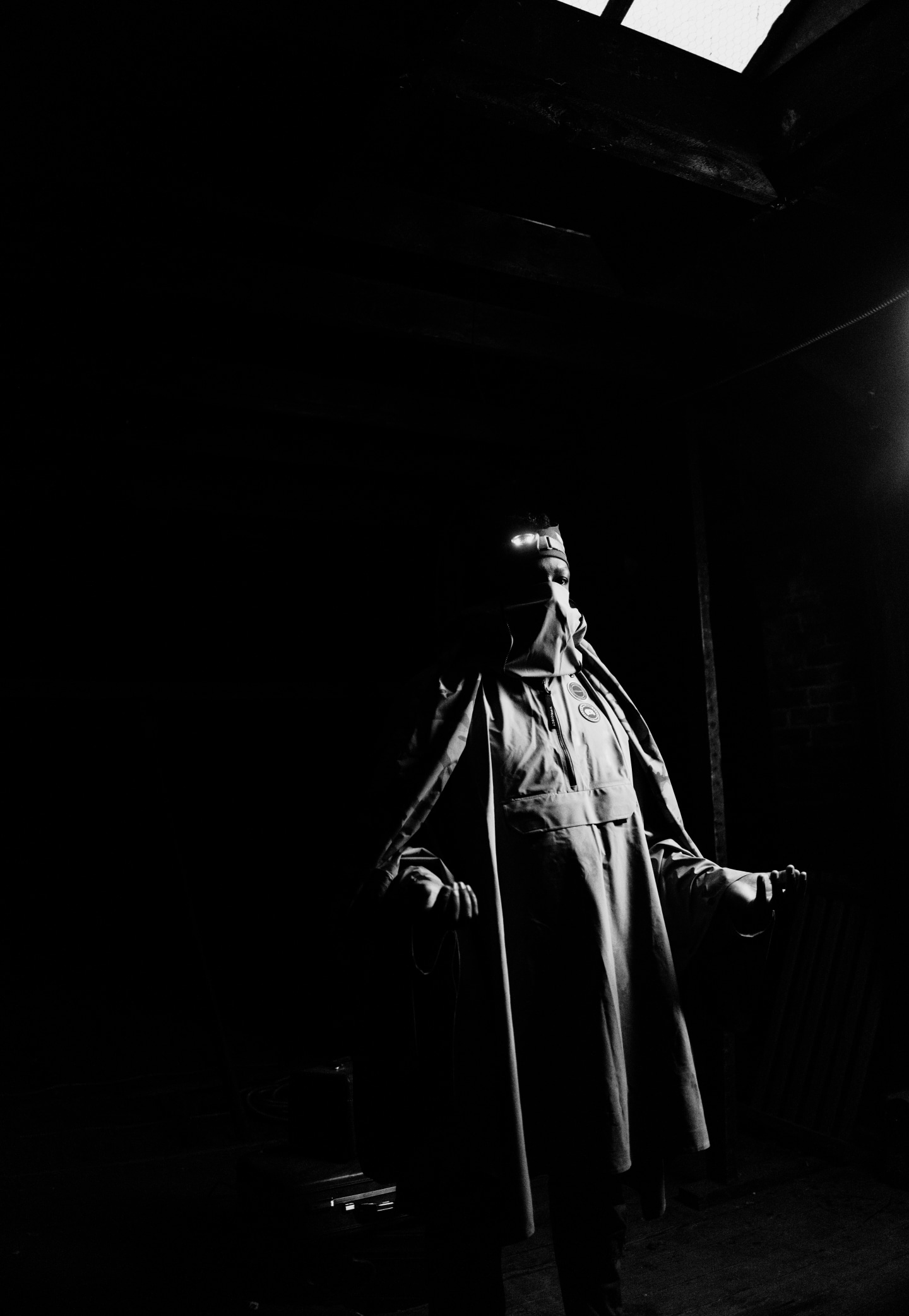

It’s like building a fire on a windy night. You have to look for a spark first, then coddle that spark, and cherish that spark so that it can grow, while wearing cold and sweaty underwear, damp socks, with numb fingers, toes, nose, and ears. You have to overcome the discomfort, cognitive dissonance, unfavorable conditions, and whatever else. Greatness is mined, that shit ain’t never on the surface. It doesn’t always have to be unpleasant, but there’s going to be the occasional drought, flood, thunderstorm, tornado, and/or mudslide.

I have a problem with the way certain stories are told and perpetuated in major motion pictures, music, and television. My major impetus is the inherent and startling disparity with which certain groups are still made to be seen as less than others in real time, as well as within the context of modern history. Those 2nd and 3rd class prioritizations that so-called “subjects of color” have been made to endure by default. All engineered towards the creation of some desired effect that benefits someone — somewhere. Or else, why keep doing it if there’s nothing to gain? The frozen indifference that a certain celebrity’s televised FUBAR may or may not receive from it’s respective academic and professional observers. There are too many examples to name, so I won’t direct any shots at any one director or production company, but I aim to be the difference that I wish to see.

Watch provided by Bezel.

Watch provided by Bezel.

If you had pursued film to the exclusion of rapping, what do you imagine your movies would have looked like?

My movies? I have so many screenplays written. I have screenplays written on legal pads from back when I was staying with my Grandma. Full blown storyboards. Character Profiles. People thought I was writing raps. I was writing screenplays. My cousin Mac was locked in on me though. He said a lot of shit, consistently, that let me know that he knew I was on some other shit. I have a cousin Tara that would do the same. She always called me “superstar” and said little slick shit like that — even back when I was still very shy and introverted. Women usually have really good intuition when it comes to stuff like that. But anyhow, I thought I was going to be a director ever since I can remember. I can’t say anything about what my films would have looked like because I’m still, hypothetically, in the middle of the creative process. For all we know, those movies may still come out, so I don’t want to speculate. I have to leave room for tomorrow and what dreams may come.

You say you saw potential in Westside Gunn as a documentary subject, but how did you initially come across him? And what did you see?

I initially came across his video for “Never Coming Home” with Tiona D. His work was niche, and even in its infancy, you could tell that its creator was sort of out there. He was uncompromising. That’s what was missing in the game, I said to myself. He just made his deposit, and the shit was unapologetic and tasteless as fuck.

The thing about me is that I’ll pull you to the side and thank you for allowing me to be a part of whatever’s HAPPENING before anyone else even has the slightest inkling of what’s about to happen. That’s because I have a keen eye for significance. I do it all the time, so motherfuckers take that kind of shit for granted. You know what I mean? Shit is almost precognitive. I came to Wes with that spirit. What Nas say, “I got that confident soul for those locked in the hole, inhumane, living hostile, opposed…”

How do you think Alchemist got a hold of your old music?

I imagine, if it’s anything close to “Project Queensbridge,” and how he was able to track down Prodigy without any email, social media, mutual acquaintances, etc … I’m sure there’s a harrowing tale of domestic espionage and international intrigue, buried somewhere deep in there, amongst the how’s and why’s.

Tell me more about “speed” — what do you think makes the diaspora distrustful of that?

I feel like there’s a collective jadedness on how Ayisyens (Haitians) feel about the way they are treated and viewed, not only at home and from home, but also, abroad. There are so many layers to this experience. Not only from the perspective of those that have emigrated to further developing nations, but also, those members of the diaspora who were born on foreign soil. We have ALL witnessed a certain kind of collective yawn from the global community, and more specifically the American government, about the political affairs of the Haitian people. So please excuse me, if it’s hard to believe that any compliment, especially one that is unsolicited is not a trojan horse or a loaded statement that’s wired to detonate on contact. It’s all post-traumatic at this point.

You write about this as a crossroads in terms of whether you wanted to step back into the booth. But when it came time to actually put the verse together, what was the linguistic or thematic road back into the rapper headspace?

I dove headfirst into the known unknown … the knocking of rust.

Tell me a little more about the Griselda machine recording process at this time. It sounds like a very social way to make music, but one that doesn’t allow a ton of top-down creative control for any one individual. I imagine your process today is much different from this, but that’s an assumption that might be wrong.

For example, Pray For Haiti was only partially recorded by me. The majority of that album was recorded in high-traffic settings where the atmosphere was more social. We had the whole building, dedicated parking, dedicated food truck, multiple control rooms, and several recording booths. Wes was having beat makers flown in every other day; it was that type of scene. We ended up recording material for that album across the span of several weeks and places: San Juan, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Atlanta, etc.

On the other hand, recording Balens Cho was what you would call an intimate affair. I engineered all my own closed sessions, took care of the art direction, and designed the merch — two totally different approaches.

When we spoke at the beginning of 2022, you told me that if someone listened very carefully to your music, they could hear minor variations in your writing depending on what city you were in at the time, who you were spending time around, etc. Are you a different rapper today than you would be if a cadre of people other than these ones had pulled you back into music? If so, in what ways?

If I go see my friend who lives in the Andes six months out of the year, I’m going to prepare for high elevation and cold. If I visit my associate that lives in the Netherlands, then I’m packing a raincoat and renting a bike. If my paramour lives near the equator, then I’m going to pack swim trunks and my Jamaican shirt with the holes in it. Same with music. Music is situational whether it’s scripted and directed, or run-and-gunned. It is subject to the forces of time and space, and nature being a major one. Biggie did a good job of exhibiting that high level of mastery on "Notorious Thugs," or something akin to what Jay did with that Juvenile “Ha” remix. You see it. It’s always been about adaptation this whole time. Survival of the illest.