Art by Annie Short.

Art by Annie Short.

It's tempting to look at 2022 as the year great music returned, glittering and triumphant, from lockdown-enforced misery. Squint hard enough and you might even see its outline in the silhouettes of megastars: Beyoncé beckoning fans back to the dancefloor, Harry Styles opening the doors to his carefully curated house, Bad Bunny's endless summer. But the truth is that this was a messier year. Some of our favorite albums this year were bold and beat-driven, and some came from major label stars. But just as many were intricate, reflective, or confounding, at odds with the mainstream narrative. Independent artists continued to release ambitious projects and go out on tour despite an inhospitable industry, and too many weren't able to do either. So, as ever, many of The FADER's favorite albums don't reflect their times; they exist in spite of them. — Alex Robert Ross, Editorial Director

50. Courtney Marie Andrews, Loose Future

On her seventh album Old Flowers, Courtney Marie Andrews went searching for answers in the dark. The Arizona-born singer-songwriter was processing the breakdown of a relationship as she wrote, grieving at her piano bench, asking questions and coming up with more heartbroken questions (“In some other lifetime, would you pick me out again?”). The process worked. By the time the first lockdowns struck and Andrews decamped to Cape Cod to complete her first poetry collection, she’d moved past that long shadow. They’re replaced on her eighth album, Loose Future, by a warm glow. Here, she sings languid melodies over blissful lap steel licks, provides herself answers to questions she hasn’t even asked herself yet, and writes a “love song without caveats” where she imagines her lover as a constellation of stars. This is the soundtrack to a half-sleep in the summer twilight, where time is elastic and the sun has singed away your worries. — ARR

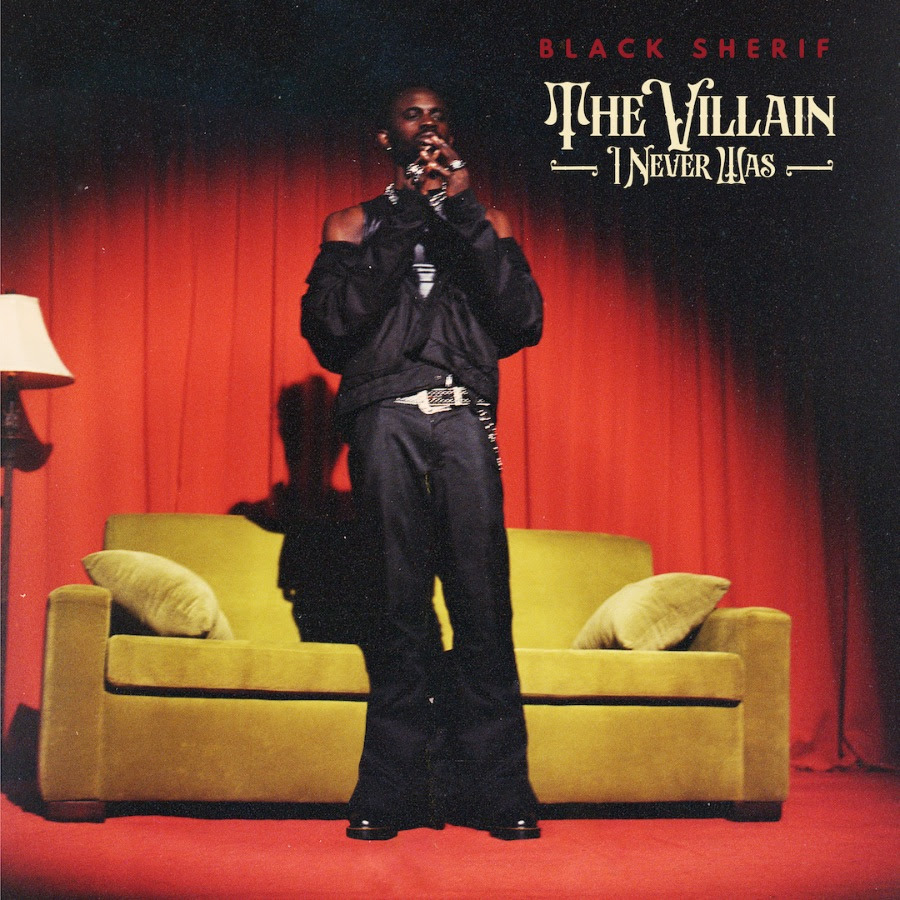

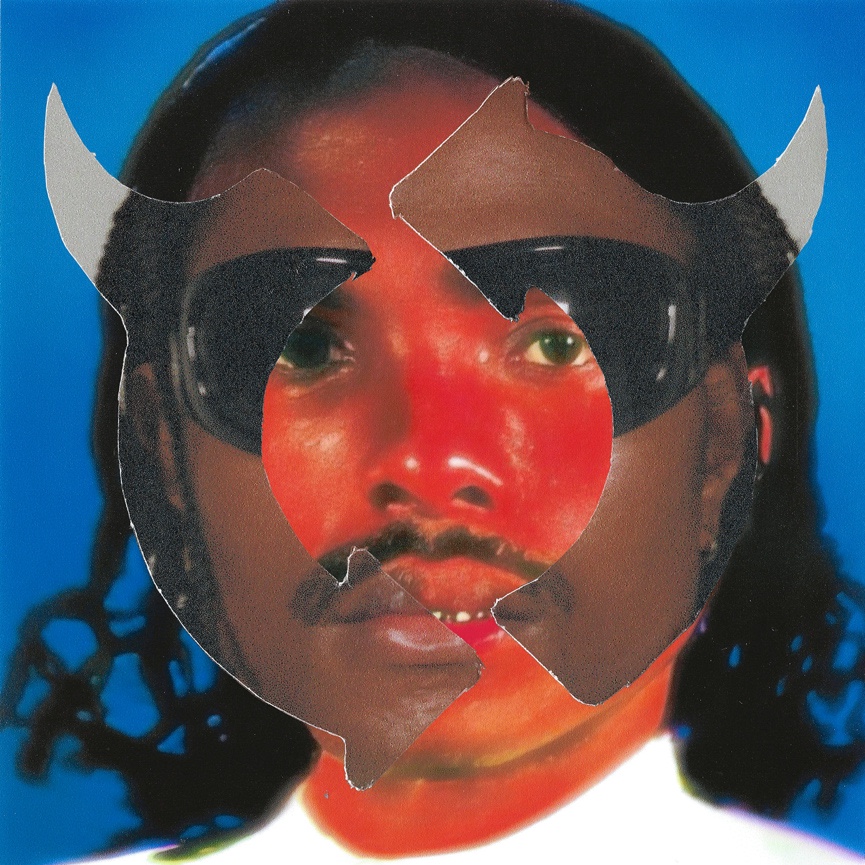

49. Black Sherif, The Villain I Never Was

After the international success of “Kwaku The Traveller” and a string of unforgettable features, Konongo-born rapper Black Sherif was supposed to spend his summer playing at festivals across Europe. A creative spirit prevailed, though, and he was possessed by a desire to complete his debut album at home in Ghana. So, instead of euphoric performances throughout the world, he spent the rest of the year slinking across studios in Accra to finish his debut album, The Villain I Never Was. “I left it all to finish this album because I wanted to give it my all,” he told THE FACE earlier this year. As achingly honest as it is insular, The Villain I Never Was is a coming-of-age epistle from the fast-rising rapper keen to make sense of — and do away with — the nihilistic public perception that his music has created. “Oil In My Head” is accessorized with thumping basslines and skittering percussion, but its subtext is an urgent plea for peace of mind. On “Toxic Love City,” he sings that he fucked up by letting someone he loved realize their hold over him. These are the words of a 20-year-old navigating life, forming new memories, and exorcising his demons. — Wale Oloworekende

48. Makaya McCraven, In These Times

Equal parts a jazz drummer at home with hip-hop’s serendipitous sample chops and beatmaker keen on exploring jazz’s improvisational alchemy, Makaya McCraven delivered his most polished and fully fleshed album yet with In These Times. The success stems in part from its ambition: McCraven first chopped, stretched, and looped a series of live recordings by a band featuring luminaries like Jeff Parker on guitar and Brandee Younger on harp. Then, he reinterpreted the resulting reimaginations alongside his band. This makes In These Times neither fully improvised nor meticulously planned out and composed, as the record instead synthesizes these two diverging creative approaches, seeking new possibilities in a reinterpreted loop or a one-off riff. Take McCraven’s drumming: it’s utterly exceptional, marrying the off-kilter rhythms of MPC-virtuosos like J Dilla to the livewire groove of classic bop, without ever coming off as too clever or academic for its own good. Even amidst a contemporary revival that has reemphasized Jazz’s groove and status as Black music, In These Times is a singular achievement, one proving that McCraven’s dialog between past and present is a fruitful one, and that he has much more left to say. — Son Raw

47. Charli XCX, Crash

Before this year it often seemed as if Charli XCX was caught between an unwelcoming mainstream and a cult fanbase convinced that she belonged among pop’s upper echelon. Crash feels like the first time she split the difference between her Hot 100 tendencies and the more abrasive production she is known for, moving past a binary that never really served her in the first place. “Beg For You,” featuring Rina Sawayama, turns teary airport goodbyes into an effervescent bop, while “Good Ones” is the sound of a thousand bad decisions set to buoyant ‘80s pop guitars and a hyper beat. Elsewhere, XCX dives deeper into a relationship flailing at the edges, turning to her relentless work ethic (as well as producers including A.G. Cook and Oneohtrix Point Never) to guide her through rocky emotional territory. The album, Charli’s last with major label Atlantic, marks the end of a professional relationship that, from the outside, often seemed like a clash of agendas. Unshackled from that arrangement, she’s now able to continue down the lane that Crash has opened up for her: pop done entirely on her terms. — David Renshaw

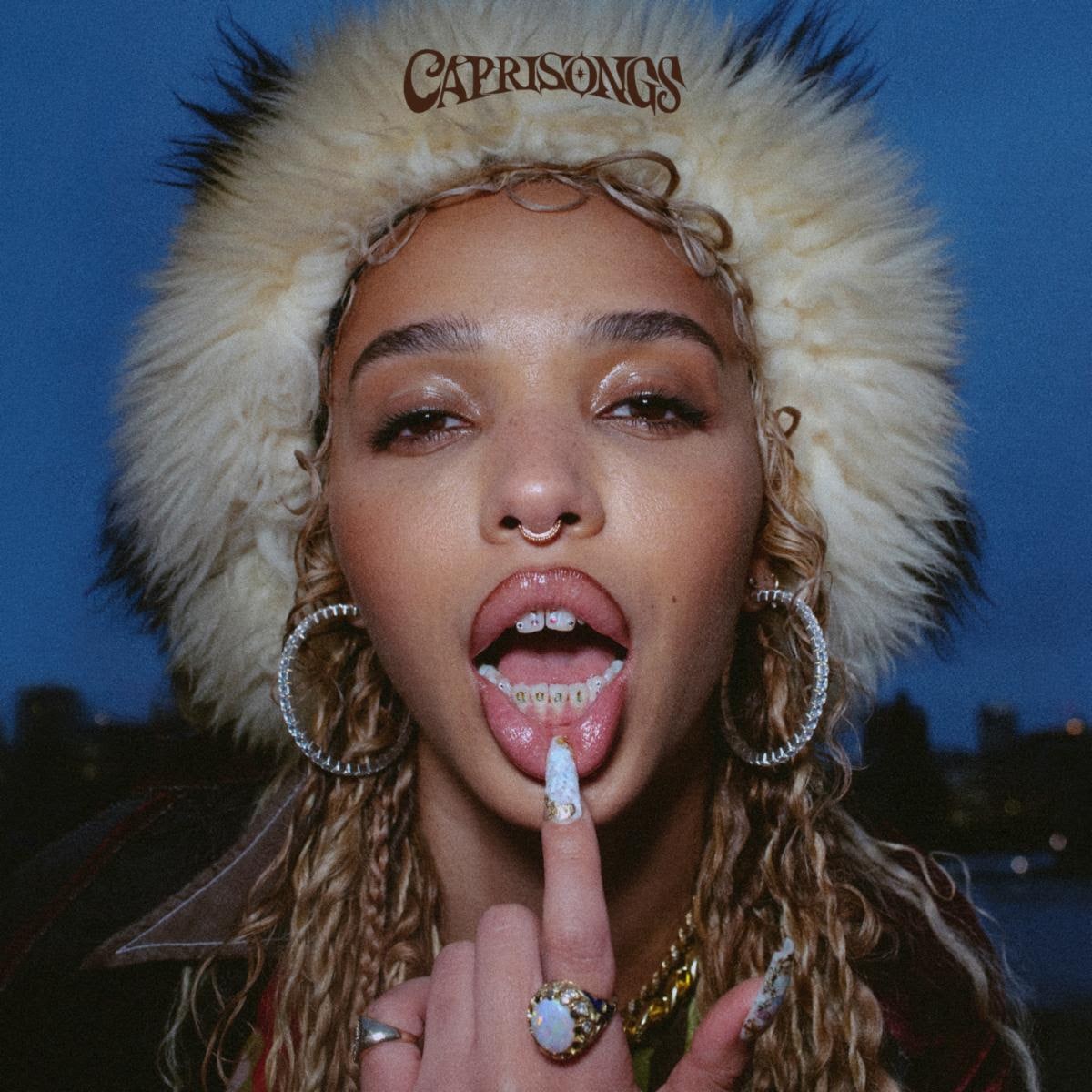

46. FKA Twigs, CAPRISONGS

FKA Twigs sounds freer on CAPRISONGS, channeling post-pandemic unity, illuminated by dizzying collaborations and grounding voice memos that capture raw moments of emotional connection. It's associative, allusive, chaotic, and real. On “Tears in the Club,” Twigs and The Weeknd fit together like matching puzzle pieces. On “Which Way” and “pamplemousse,” she channels the abstract refractions of SOPHIE and Charli XCX’s proto-hyperpop as much as she does the Spice Girls. The ease with which she moves into dancehall territory on “Jealousy” alongside Rema feels chameleonic. When she stands alone, as she does on “Meta Angel,” she’s reflective and honest, engaging in deep conversation with her past self. Unburdened by the expectation of making a proper follow-up record — CAPRISONGS is billed as a mixtape — Twigs pushes herself emotionally and stylistically, revealing more of herself, taking risks, and encouraging all of her collaborators to do the same. — Larisha Paul

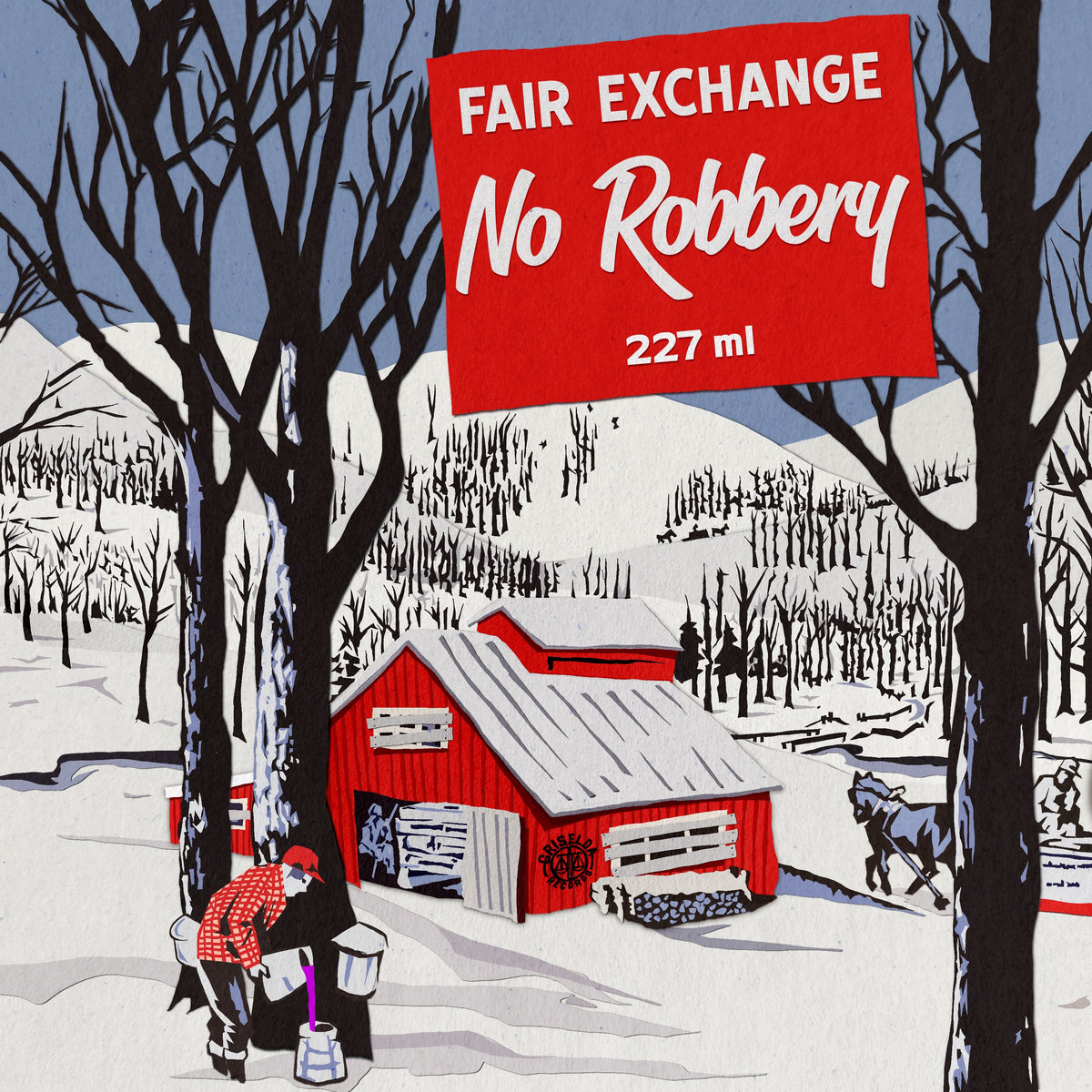

45. Boldy James & Nicholas Craven, Fair Exchange No Robbery

Rhyming with Prodigy’s menace, Pac’s emotion, Guru’s restraint, and a Detroiter’s sense of groove, Boldy James’ 2022 proved that last year’s incredible run of projects alongside super-producer Alchemist was no fluke. In September he teamed up with Montreal producer Nicholas Craven for Fair Exchange No Robbery — a soulful take on the lo-fi true crime dominating the hip-hop underground recorded in just three days. Equally at home boasting over the hectic boom-bap of “Stuck in Traffic” or delivering a haunting, near drumless extended metaphor on “Power Nap,” Boldy captures the dizzying highs and stomach-churning lows of the drug life in vivid detail, while Craven selects the perfect loops to heighten the impact. For both emcee and producer, the key is to do less to achieve more: Boldy’s monotone flow makes even the tiniest vocal shift feel titanic, while Craven’s minimalist production never gets in the way of the storytelling, preferring one perfect moment to a hundred unnecessary variations. From its clever lyrical concepts to its inscrutable samples to its cover, the best in rap this year, Fair Exchange No Robbery is a product of care and impeccable craft. — SR

44. Saba, Few Good Things

On his third album, Chicago rapper-producer Saba deals with the repercussions of loss. Taking a softer and more melodic approach than he did on on 2018’s Care For Me, his colorful wordplay reveals an artist at peace with his past. “We come from fifty-cent bags of candy and penny pinchin’,” he raps on “2012,” the album’s penultimate track. “It’s like a wishin’ well if we gave the concrete our wishes,” Reflective and raw, like the first light of dawn beaming through a grimey window, it’s introspective without being preachy, delving into the ways memories can hold us back from shifting our perspective. Money may be top of mind but the rapper refuses to let it define him, as he spits on the Fousheé-assisted “Make Believe”: “I got everything I could ever need, and I try to keep that in mind anytime I meet a man tryna sell a dream.” — Sajae Elder

43. Young Miko, TRAP KITTY

Rising from Añasco, Puerto Rico, emerging queer rapper Young Miko moves past TikTok virality on her debut EP TRAP KITTY, bucking pop reggaeton trends and claiming necessary space for neo-malianteo while inviting listeners into the world of a young stripper named Riri. Inspired by her best friend, an exotic dancer of the same name, Young Miko tells Riri’s story through dreamy fusions of trap beats and sharp synths, interludes and skits, and Spanglish lyricism that reflects her gender-hopping blend of energies. Alongside Brray, “Bi” unapologetically explores sexual fluidity, the standout track “Riri” narrates the story of a modern, digital “bad bitch,” while the Mauro and Caleb Calloway-produced track “Putero” serves as the perfect ending: a love letter to nightlife hustlers and sexually liberated women, presented on a mod-Miami bass infused beat. — Jennifer Mota

42. Black Country, New Road, Ants From Up There

Isaac Wood left Black Country, New Road on January 28, 2022. The group’s brilliant, brooding frontman and chief lyricist had been, to many fans, metonymic for the band as a whole, crystalizing the mathy, klezmer-infused art-rock instrumentals of their 2021 debut, For The First Time, with his self-deprecating spoken-word monologues. But eight days before the release of its follow-up, he quit, citing a mental health emergency so acute he was finding it “difficult to play guitar and sing at the same time.” Nevertheless, Ants From Up There arrived on schedule. Its 10 tracks — half of them certified epics running well past the six-minute mark — are the first and final studio recordings of a super-talented septet in peak form, at least for now. Where FTFT was sardonic and guarded, BCNR’s sophomore effort is wide-eyed and vulnerable, a symphony of perfect love songs from a since-exploded solar system, still shining through the tragic circumstances of their crash landing on earth. Nearly a year later, tracks like “Good Will Hunting” still feel sad, silly, and full of life all at once. — Raphael Helfand

41. Callous Daoboys, Celebrity Therapist

Atlanta mathcore provocateurs The Callous Daoboys recently released a T-shirt emblazoned with a slogan that feels like a mission statement for their music: “HUFFING PAINT THINNER MAKES YOU INVINCIBLE... WE’RE NOT KIDDING.” Legally it feels prudent to point out that this is bad advice, but spiritually it’s key to understanding their prankish sense of humor, their lobotomized dirtbag-prog riffing, and the unsettling grime that coats every corner of their third album Celebrity Therapist. Tracks like the self-lacerating “A Brief Article Regarding Time Loops” and the punishing closer “Star Baby” burst through the borders of seemingly distant pockets of the heavy music universe — gnarled hardcore, emo anthemics, and even brittle prog-pop — like the Kool-Aid Man with a God complex. Walls between sounds, they seem to suggest, were meant to be shattered — and if it takes inhaling industrial chemicals to work up the courage to dive headfirst into the masonry, so be it. — Colin Joyce

40. 454, Fast Trax 3

454’s debut album 4 REAL, released in 2021, transcended the wave of hype for PluggnB, a swooning, Auto-Tuned splice of trap and R&B. The unique compositional flair he demonstrated on that project is bolstered on his latest tape Fast Trax 3 by a surge of confidence. His lyrical reflection — on his tragedies, loves, drugs, and come-up — hits harder, even when it’s plainspoken. “Niggas can’t stand facts, I’m the motherfucking man,” he raps on “WONDERRR,” which adds thumping drums to a sample of Wayne Wonder’s “No Letting Go,” pitched up to the texture of cotton candy. The breadth of his growth as a producer is most immediately captured on “NUMBERS GAME” and “TRAILBLAZER”: 454 unleashes a rocket-fueled flow over dreamy melodies on the first song, and towards its conclusion, cyclic, time-stretched breakbeats begin to fade in, announcing the transition into the next track, where the percussive mayhem is dotted with fairy-light synths. Like the best mixtapes, Fast Trax 3 feels like a peek through a crack in a studio door to witness raw creative process; but the amount of growth it demonstrates, too, is as rare as it is delightful. — Jordan Darville

39. First Hate, Cotton Candy

For childhood friends Anton Falck and Joakim Wei Bernild, making fanged pop music started out as a countercultural thrust against the grain of Copenhagen’s punk scene. Traces of that hardcore spirit are still present (especially in Falck’s dagger-like vocal delivery) but First Hate want to make you dance, and never has that mission been more fully fulfilled than on Cotton Candy, their nocturnal romp of a sophomore record. “The heart is a muscle, and I’ve gotta move,” they declare at its onset, setting their sights on love, lust, and late capitalism — even brazenly all at once on lead single “Commercial.” For each of its blinding highs, there’s a bellowing low, and First Hate excel at making both feel bold, earnest, and often hilarious: “Eat your spaghetti to forgetti your regretti,” they deadpan on “What’s the Matter Boy.” It’s a mandate you’d be hard-pressed to refuse. — Salvatore Maicki

38. Rachika Nayar, Heaven Come Crashing

“I’ve always loved music that feels like it brings you to a point of overflowing,” Rachika Nayar told The FADER earlier this year. “Something inside of you is so overwhelmed, so completely obliterated or annihilated, you lose your sense of self entirely, and something new inevitably comes out of it.” The Brooklyn-based artist hinted at this sort of power on her debut, Our Hands Against The Dusk, layering guitars over guitars to produce a kaleidoscopic vision of Midwest emo and ambient music. Heaven Come Crashing, its follow-up, is orders of magnitude larger. This is a titanic album, built around towering breakbeats and transportive electronic peals; it owes as much to Tiësto as it does to Texas Is The Reason. Nayar incorporates vocals here for the first time too, collaborating with the ambient-acoustic artist Maria B.C. on the album’s two most colossal tracks, “Heaven Come Crashing” and “Our Wretched Fate,” both of which build to rapturous crescendos. But Nayar knows when to pull back too, often for minutes at a time, allowing those delicate guitars to seed and sprout in the rubble. — ARR

37. Vince Staples, Ramona Park Broke My Heart

Ever since his mainstream breakthrough with Summertime 06’, Vince Staples has cannily avoided getting boxed in as a chronicler of Black trauma, whether by collaborating with electronic music innovators on Prima Donna and Big Fish Theory or indulging in party-ready So-Cal rap production on FM!. But on his fifth album, he squares that circle, dedicating the record to the Long Beach neighborhood that raised him, without indulging in the glorification of street life or wallowing in sonic darkness for its own sake.

Initially, the record goes down easy, introducing sticky hooks to laid-back beats seemingly custom-made for a magic hour drive across Californian highways. Never has Staples engaged so deeply with classic G-Funk than on "DJ Quik" – a dedication to Los Angeles’ other gangsta rap super producer. Staples’s musings and recriminations however, whether speaking on romantic entanglements or gang violence, play off the music’s feel-good vibes by highlighting the human cost of the conflict and tension behind every Long Beach sunset. The resulting album is contemplative and acidic in equal measure: a mainstream-oriented, major-label album from a man who still views himself as an outsider, commenting from the margins. Previously, this approach could have backfired, getting Staples branded as a cynic mostly interested in trolling his audience. On Ramona Park Broke My Heart, the refusal to play to preconceptions, all while subverting the traditions of West Coast hip-hop, make for a magnetic record, perfectly balancing sly commentary and heartfelt emotion. — SR

36. Kornél Kovács, Hotel Koko

As a producer, DJ, and founding father of gonzo Stockholm dance collective Studio Barnhus, Kornél Kovács has always been guided by a sharp and squiggly curiosity. On his third studio album, that leads him to the lobby of the towering Hotel Koko, where the hallways stretch on infinitely, room service caters to every desire, and the presidential suite sits in the clouds. None of this is articulated, of course, but rather evoked through cosmopolitan sax licks and beaming bells that would be as keenly fit for a chrome-plated elevator as they are for the club. This being a Kovács record, things still get delightfully weird — most pointedly when he mangles with the tempo of “Szakad,” or generates a ceaseless thump on “Usch.” Equally as checked-in are his guests: “Castles'' gets its taffy-like pull from Kamahelo Khoaripe of Swedish-South African techno supergroup Off The Meds; Costa Rican singer Mishcatt’s delivery on “Goofy” is overhauled by skittering drum and bass; and Aluna’s vocals gild the album’s melancholic pop apex, “Follow You.” Kovács doesn’t just hope you’ll enjoy your stay. He practically guarantees it. — SM

35. Gilla Band, Most Normal

“At the end of the day, that’s football” is a hilariously innocuous phrase, but then Irish four-piece Gilla Band have always excelled at championing the absurd power of the mundane. Alongside vocalist Dara Kiely’s thoughts on sports, RyanAir, and his shopping trip around Dublin looking for a shitty pair of bootcut jeans, however, there’s a newfound directness on the group’s third full-length. Presumably titled Most Normal in acknowledgment of it actually being their least comfortable work to date, the album proves Gilla Band are assured enough to push into vaster, starker, and more terrifying realms than ever before. That means lines like “I’m in between breakdowns constantly” and “Basically I get inevitable depression when I do nothing,” ruminations on aging and self-disgust sitting among those funnier moments in Kiely’s characteristically caustic drawl. Behind him, Alan Duggan, Adam Faulkner, and Daniel Fox vibrate like a machine, leaning further still into the twisting, boundless possibilities of the studio with distortion that feels stretched-out, sprawling, slow-dancey, snarling. Surprise licks of sweet melody glimpse through the noise. Splatters of bright, cartoonish chaos splay over moments of plaintive calm, like barbed wire cutting through water. Beautiful, uneasy, funny, devastating, and oddly tender, Gilla Band prove themselves singular all over again. — Tara Joshi

34. Feid, Feliz Cumpleaños Ferxxo: Te Pirateamos El Álbum

Once an underdog in the game, Feid has solidified a place in reggaeton thanks to his romantiqueo, pop reggaetón rooted in emo lyricism. Also known as Ferxxo, Feid was well known for writing with artists like J Balvin, but his star has risen since then. This release was planned for December but leaked in early September; it became officially available 24 hours later and was an instant success. Comprising Feid's most popular songs this year, including “Feliz Cumpleaños Ferxxo,” “Si Te La Encuentras Por Ahi,” “Ferxxo 100,” and the iconic sadboy anthem, “Normal,” Feliz Cumpleaños Ferxxo: Te Pirateamos El Álbum solidifies Feid’s status as one of reggaeton’s global superstars, blending romantiqueo ballads with eclectic, rhythmic sounds. — JM

33. Dazegxd, vKiss

Dazegxd’s earliest encounters with the wildest corners of dance music occurred not in a club, but on the internet. In an interview with Newtown Radio, Daze said they constantly listened to online radio stations as a middle schooler, which sparked an early love for trance, jungle, house, and even stranger sounds. As a result, Daze said, “I do it all.” The expansive dancefloor epic vKiss feels like a love letter to those boundary-pushing broadcasts Daze grew up listening to, full of nostalgic, Technicolor melodies that pay tribute to the ecstatic history of club music that has come before. Whether drawing on euphoric garage, intimate R&B, dizzy house, or other rave refractions, Daze’s productions feel powered by the joy of discovery and a genuine affection for whatever sound captivates them on a given track. Part of the truest joy is in the boundlessness of the project. Unconstrained by the rigid genre strictures enforced by decades of dancefloor dogma, Daze is free to make trance on one track, drum and bass on the next, and pitch-shifted pop on another. Like any great radio show, you never know exactly where it’s going to go next, but you can trust it’ll satisfy. — CJ

32. Obongjayar, Some Nights I Dream of Doors

Obongjayar’s refusal to stick in any one box makes for an album rich in texture and innovative in form. Some Nights I Dream of Doors hops between acoustic soul and hip-hop, bound together by Afrobeat. At its center is Obongjayar’s shape-shifting voice, moving from a guttural lower register to a lilting falsetto. It's equal parts bluesy rasp, soaring soprano, and accented call and response in the tradition of Nigerian icons before him. Throughout, Obongjayar wrestles with guilt, duty, and uncertainty. While the intro track “Try” wonders if better days are ahead (“Times are overbearing / Winning odds are slim”), “Wrong For It” finds the singer talking himself out of self-imposed obligation. “Stop trying to please everyone else / Stop trying to fix everything,” he sings over Nubya Garcia’s stunning saxophone. From the righteous rage of “Message In a Hammer,” calling out state violence and corruption in Nigeria, to memories of love’s quiet moments on “All The Difference,” Obongjayar places soul-baring vulnerability at the fore. — SE

31. IDK, Simple

Despite its title, IDK’s collaborative EP with Kaytranada is a complex thing. Named after Simple City, the D.C. neighborhood where the rapper grew up, its vibrant production is groovy and twinkling and somehow makes difficult conversations about his childhood haunts seem uplifting and irresistibly danceable. Simple is also lyrically succinct. Bookended by two interludes that find him on a Paris-bound flight and one back to his hometown, the album finds IDK thinking about his upbringing (“Most of my niggas never had a Thanksgiving / So instead of givin' thanks, my niggas takin' what's given”) and ideas about love, family, and grappling with fame (“I feel the love and the hate piercin' the air”). “I wanted to create an album where people can dance to real shit,” IDK said about the album just ahead of its release. On standouts like “Dog Food,” alongside frequent collaborator Denzel Curry, and “Zaza Tree,” IDK does exactly that. — SE

30. Open Mike Eagle, Component System With The Auto Reverse

Across a career full of unexpected and thoughtful left turns, Open Mike Eagle often came across as misunderstood — the smartest man in a room full of vultures unwilling to see the full extent of his humanity. On Component System, however, Mike narrows his focus via a bar-heavy tribute to the rap fandom of his youth, zeroing in on an aesthetic that foregrounds his hip-hop bona fides instead of his eclecticism. Whether paying homage to deceased legend MF DOOM, geeking out with friends over Diamond D and Madlib beats, or venting about the state of his career and the weirdness of post-pandemic life, Mike’s music has never felt more engaging and impactful. Above all, it’s a genuinely fun listen, one full of references to cult Marvel heroes and musical nods to Chicago and Los Angeles’ rap lineages. These touches of levity make Component System all the more welcome in a scene that usually indulges in gritty darkness for its own sake, making it the perfect album to give the Open Mike Eagle cult following a well-deserved signal boost. — SR

29. Omah Lay, Boy Alone

At the end of his breakout 2020, Omah Lay released the celebratory five-track EP What Have We Done, bathing in the glow of newfound stardom and the attention of icons like Wizkid and Justin Bieber. The two-year gap between What Have We Done and his debut album, Boy Alone, has seen Omah encounter the darker side of fame. The first words he whispers — “Only the real fit recognize” — hint at the pain he’s felt in the intervening years. Boy Alone bears all the melodrama and descriptive eloquence of Omah’s songwriting but it is undergirded by a pervading feeling of despair, no matter if he’s describing sex on “bend you” or asking a lover to teach him how to show affection on “how to luv.” Much of Omah’s earlier works were characterized by a youthful curiosity about love and romance that often flatlined somewhere in the middle of the songs. Boy Alone, dense and heavy, is a narrative level-up — held together by delirious, almost-obsessive reflection and tight-knit world-building. — WO

28. FLO, The Lead

London newcomers Flo channel the sassiness of Spice Girls and Destiny’s Child-era girl power on their debut project, Jorja Douglas, Stella Quaresma, and Renée Downer sounding like an A1 girl group. Although it only features four tracks and comes in at under 15 minutes, not one moment is wasted. They paint a nuanced picture of young women undergoing the trials of love: “Not My Job” is playful, while “Immature” offers a reality check to entitled lovers. The unbothered energy of “Cardboard Box” is upbeat but assertive with its proclamation of the listener’s self-worth. Even if you’ve never wanted to shoot a text to your ex’s homeboy or would never openly admit that his mom was a bitch, Flo make both ideas feel real and relatable. — Gyasi Williams-Kirtley

27. Christina Vantzou, Michael Harrison and John Also Bennett, Christina Vantzou, Michael Harrison and John Also Bennett

The self-titled collaboration by Christina Vantzou, pianist Michael Harrison, and synthesist John Also Bennett is a monument to the power of music guided by intuition and improvisation. Together, with Vantzou serving — per the project’s Bandcamp page — as a “witness and guide,” the trio make raga-inspired pieces that roam between hazy themes and moods, settling into pockets of comfort amid the uncertainty of their wandering, but never for too long. There are practical factors that one might credit for the specific dimensions of this record’s spectral movements — a dedication to the tuning method of just intonation, an affection for North Indian classical music, Harrison’s background as a protégé of minimalist composer La Monte Young — but to try to pin down Christina Vantzou, Michael Harrison and John Also Bennett would be to miss the point. The record is allusive and illusory, each melody tumbling associatively from the last. Like a dream, moments snap into focus with startling clarity — you’re in a new space entirely, but unsure exactly how you got there. — CJ

26. Sault, Air

Spring, 2022. Flowers continue their journey from bud to bloom. Winter’s pall has dissolved from the sky. Our earth continues its sacred tradition of rebirth. How appropriate that it was in this context that Sault shared Air, a transformation of the spectral U.K. group from the world’s best neo-soul group into a classical collective. Across seven songs, Sault becomes an orchestra and choir as vast, enveloping, and nurturing as our own atmosphere. And yet, despite the changes, Sault are still the guardians of Black musical tradition. Closing track “Luos Higher” is speckled with Afrobeat melodies, and “June 55” contains the most overt allusions to their beginnings: its horns bellow out motifs that beg to be sampled while the voices of Sault ripple with classic soul music tradition and the playful passion of something entirely new being birthed. Air delivers its statement of purpose — the only lyrics on the album — on the final third of “Time Is Precious.” “Don't waste time ’cause time is precious / It's your only time you've got here / Life will always bring its pressures / Use it wise and keep those treasures.” It’s vintage Sault: bursting with ecstatic wisdom and dimension beyond the senses. — JD

25. Alvvays, Blue Rev

The breathlessness of Alvvays’ masterful third album is by design. In the wake of their sophomore LP, 2017’s Antisocialites, the Toronto five-piece spent years tinkering with the songs that would follow, a process further delayed by burglary and a flooded basement. When at long last it came time to flesh them out with producer Shawn Everett, he encouraged the band to run through the entire tracklist front-to-back on their second day in the studio. Dense with distortion, the urgency of this power pop exhibition is what’s most immediate, but give into the sugar rush a few times and its meticulousness reveals itself. In the world of Blue Rev, sentiments feel kaleidoscopic but no two choruses within the same song ever sound quite alike (save for the jubilant “Many Mirrors,” which intentionally revels in repetition). The lyrics, alive and alliterative as ever, etch out stories of casino comedowns, relationship-altering earthquakes, and unexpected pregnancies, each running parallel in their dissatisfaction with “the way life’s shaking out.” As songwriters, Molly Rankin and Alec O’Hanley share an innate talent for making the seemingly inconsequential — the condensation on a truck’s windows in “Tile By Tile,” a suspicious slide down the banister in “Velveteen” — feel monumental. Notwithstanding these downtrodden character studies, Blue Rev doesn’t pity itself. Somehow, when amalgamated, the devastating details begin to sound like epiphanies. Sure, some of the optimism of Alvvays’ earlier work may have dimmed, but their sense of reverie is fully aglow. — SM

24. Ari Lennox, age/sex/location

Ari Lennox’s conversational writing and soothing voice have always invited intimacy, but age/sex/location is more than just a catch-up with an old acquaintance. It’s the laughs you have with a friend you haven’t seen in years while sharing stories of past mistakes and savoring the wisdom and clarity that comes with making them. The buttery keys and sultry basslines that caress her words, provided by Organized Noize and longtime collaborators like Elite, give her songs the ambiance of a candlelit smoky club. On age/sex/location, Lennox opens up once again with songs of desire that detail bumps along the road to pleasure, only this time, she’s focused on satisfying herself and communicating what she wants without making any concessions. “Young Black woman approachin' 30 with no lover in my bed / Cannot settle, I got standards,” she firmly states on “POF.” She makes room for flings and flirtations too, but when she’s calling someone over to waste her time or getting caught up in a feisty back-and-forth with Lucky Daye, it starts and ends on her own terms. — Brandon Callender

23. Harry Styles, Harry’s House

Harry’s House is Harry Styles’s boldest embrace of pure pop music since his stint in One Direction. His grandiose pop statements — “Music for a Sushi Restaurant,” “Cinema,” “Daydreaming,” “As It Was,” and even the more subdued “Keep Driving” and “Satellite” — don’t pretend to disguise themselves in lush refractions of rock or introspective indie music. That isn’t who he is. Three albums into his solo career, Styles finally sounds unhindered by his past and himself. No longer trying to fit into a box of expectations, he’s free to pull on a creative thread and see what happens as it unravels in front of him. He's more open lyrically, too, zooming out to see the bigger picture of the complicated interpersonal interactions he’s shared on past records. Songs like “Matilda” and “Little Freak” find the singer approaching a breakthrough in the way he assesses the emotional output of the people around him — rather than settling for a stubborn projection of how those exchanges made him feel. “Grapejuice” and “Love of my Life” are tender, ruse-dropping confessionals. He’s an observant songwriter repacking intimate intricacies with lyrical simplicity colored with epic pop production. He doesn’t have to clamor for the spotlight; he already commands it with ease and poise. — Larisha Paul

22. Bladee and Ecco2k, Crest

On “Yeses (Red Cross),” a central track on their collaborative album Crest, Bladee and Ecco2k chant a single word like an incantation: "euphoria." It’s a striking combination of syllables, all the open vowel sounds fluttering away in the breezy falsetto, but it also is a simple summation of what the pair are aiming for on the record — a stubborn, relentless dedication to finding and creating ecstasy and joy in a time of widespread suffering. Or as Bladee puts it simply on another track, “Beauty is my drug, I’m the pusher.” These sorts of New Age-y ideals suit the pair’s imagistic, otherworldly approach to pop music — in which emotional truths have always been communicated cryptically, but with near-religious devotion. But here, they strain toward heaven with every ounce of their being, trying to pull a little of that beauty down to us. Can they create heaven on Earth? Probably not. But the pillowy comforts of this record are proof of the power that they can access just by trying. — CJ

21. Bjork, Fossora

Björk’s 10th album continues the artist’s main thematic preoccupation: finding lessons for human connection in the natural world. Where mutual coordinates, volcanoes and tectonic plates facilitated this idea on previous records, on Fossora, Björk looks towards the soil and underground, to fungi and roots. Like all good Björk albums, its aim is to counsel you until you come to a place of greater emotional respect and intelligence. Björk goes on the journey with you, as she tries to find grace and harmony among a chaotic soundscape of gabber-inspired horn and wind instruments which sound like warring neuroses, or all the stories we tell ourselves that prevent our connection to one another. The sound design is spectacular, video game-like in its ambition. On “Ovule,” for instance, every single embellishment sounds egg-like and globular. Fossora isn’t a world that will come to you, though — it’s one you must step into if you want to come out feeling better connected on the other side. — Emma Madden

20. Aldous Harding, Warm Chris

Aldous Harding's patient, elliptical folk became even more surreal on Warm Chris, her fourth album. Here, she leans into the strange voices, malcontent rhythms, and melting imagery of her previous record, Designer, turning the whole thing into a pastoral circus show, filled with fiendish characters whose crowed voices are profoundly wise and instinctively untrustworthy. There are, occasionally, moments of almost alarming lucidity — such as the startlingly clarified lyric "All my favorite places are bars" on the single "Fever," a line so plain it almost strikes like a jumpscare in a horror film. But, for the most part, this is music presented like a film of watery tea leaves. Like so many of the best records of 2022, Warm Chris ends with a sharp reminder that impending doom is around the corner, with Harding's most twisted caricature coming out of the shadows like the grim reaper — screeching "here comes life with his leathery whip!" — and turning death's specter into a gnarled S&M freak. — Shaad D'Souza

19. Lucrecia Dalt, ¡Ay!

¡Ay! can be enjoyed from virtually any angle. For non-Spanish speakers coming in completely cold, it can be absorbed as a sound tapestry, a lattice of analog and synthesized sounds interwoven in spindly ebbs and dense flows beneath Lucrecia Dalt’s otherworldly alto. Those more familiar with the language and the myriad musical styles of el mundo hispanohablante will appreciate Dalt’s poetic, allegorical lyrics and her brilliant blending of traditional styles such as son and bolero with warped transmissions from deep space. But repeat listening and a bit of background reading reveal ¡Ay!’s purest essence. Over 10 meticulously arranged tracks, Dalt tells the story of Preta, an extraterrestrial, post-physical entity who creates a humanoid form for herself through cosmic jetsam, materializes atop a Mallorcan mountain, and descends to decolonize society of its myopic preconceptions. Time and love, she explains, are not fixed, linear entities. Rather, they gush forth in cascades, receding into tributaries and returning to their source in an endless, omni-directional flow. — RH

18. Asake, Mr. Money With The Vibe

After a few years spent trawling Afropop’s underground, 2022 was the year that Asake finally emerged as a hitmaker to rival anyone in the genre. The singer remade the genre in his image with his signature blend of Fuji, hip-hop, and amapiano instrumentals, stacked crowd chants, and an unmissable lyrical style inspired by the backstreets of Lagos Island. All of these elements, tied together by Asake’s magnetic presence, coalesced into an unprecedented run of hits that made the 27-year-old’s voice an unmissable presence on Lagos radio and beyond. The September release of his debut album, Mr. Money With The Vibe, was treated like his true arrival. Here he playfully engages with themes of love and destiny while lightly tweaking his winning formula with live arrangements from track to track. MMWTV, capped at 30 minutes, plays at an unrelenting pace: “Dull,” the album’s operatic opener, unfurls into “Terminator,” a ghetto love tale that luxuriates in its gritty street-pop origins. Much of what makes MMWTV an engaging listen is how firmly rooted Asake is in his musical convictions: On “Nzaza” he sings about his headstrong devotion to making a success of his career while “Joha” is both a stunning Fuji-inflected heat-rock and a vigorous summons to the dancefloor. Some of the biggest debates in Afropop in the last decade have been predicated on what the formula for international success is, but with MMWTV, Asake shows that unflinching conviction is the key. — WO

17. Cate Le Bon, Pompeii

Cate Le Bon’s Pompeii doesn’t merely fill time; it mutates the texture of temporality, turning linearity incoherent and absurd. Listening to it feels like landing back on local time after spending a century looping around space in a tiny vessel. On Le Bon’s sixth album, everything sounds hauntingly insular and space-sick: from the brittle bass tones through to the drippy City Pop-inspired synths and oh, those saxophones! You’ve never heard a saxophone like this before: rutilant yet eerie, ancient yet entirely fresh. Each note unmoors and reassures you, like it’s unearthing your nerviest emotions and encouraging your detachment from them. “Sound doesn't go away / In habitual silence / It reinvents the surface / Of everything you touch,” Le Bon sings on "Dirt On The Bed," a lyric that perfectly encapsulates the listening experience of Pompeii — an album that takes full advantage of the ability of sound to distort your perception of space, surface, and time. — EM

16. Steve Lacy, Gemini Rights

On Steve Lacy’s Demo the world was introduced to “the guitar player from The Internet,” a young kid who made genius-level chord progressions on his iPad using GarageBand. Fusing longing lyrics with a funk undertone, it quickly established Lacy’s signature sound. But on Gemini Rights, Lacy comes into his own. His second studio album is straightforward in a way his previous records weren’t: this is bittersweet relationship drama turned into poetry — songs that are so personal you almost feel like a fly on the wall of a confidential and pricey therapy session. Although singles “Bad Habit” and “Mercury” have taken over TikTok and radio like invasive species, Gemini Rights might be considered more of a vibe than a culture-shifting body of work. It gives listeners the license to turn off the noise in their heads and live inside Lacy’s for a while. It charts his honest and messy metamorphosis into the artist we know now: the give-no-fucks, disposable camera-smashing, Bottega Veneta-sporting Rick James acolyte we know today. — GW-K

15. Jenny Hval, Classic Objects

Classic Objects contains multitudes. On its face, it’s Jenny Hval’s simplest album to date — but its outwardly clean, catchy cuts have false bottoms. Consider “Year of Sky,” a mid-album track that begins with a simple, diaristic datum: “It’s 9 a.m.,” Hval declares, “but it doesn’t matter / Place and time / Is only ever referenced / As an entry point, / Like, ‘Oh, 9 a.m., I have those.’” Elsewhere, a trip to Prada Marfa devolves into a psychedelic, post-apocalyptic journey through self and space; a coming-of-age tale encounters a group of Australian nurses who recite French philosophy like scripture; and an unsuccessful musician’s sad-sack story gives way to a stream-of-consciousness poem from the point of view of Hval’s dog, Cleo. In an album of “plainspoken pop songs,” the only connective tissue is a sensuous sonic palette and Hval’s tentative yet towering soprano. But that’s more than enough: Classic Objects is an infinitely explorable album from one of the world’s most intriguing musical minds. — RH

14. Jockstrap, I Love You Jennifer B

U.K. duo Jockstrap work in a unique way: together, but apart. Georgia Ellery, who also plays in Black Country, New Road, writes the songs and then sends the demos to producer Taylor Skye to turn them inside out. The result, as captured on I Love You Jennifer B, is an album on which Jockstrap throw the past 60 years of popular music into the mixer and come out with a melange that touches on everything from to neoclassical to Motown and happy hardcore. What could come across as gimmicky or exhausting is the strength of Ellery’s songwriting: something as beautiful as torch song “Concrete Over Water” would sound timeless in any era. What makes it remarkable is the way it takes off on a new plane halfway through, as hard-hitting drums take over and a cut-up choral sample enters the mix, before returning to where it started. Elsewhere, Jockstrap songs can be more straightforward; “50/50” is a sweaty rave banger that captures the album’s sticky-floored heart, while “Glasgow” is the kind of twee indie song their label Rough Trade made their name with. It’s the unpredictability that makes the album so magnetic and impossible to ignore. — DR

13. Kim Petras, Slut Pop

Any 150-word blurb trying to outline the gorgeously puerile brilliance of Slut Pop will feature more words than the record itself. Kim Petras's 2022 EP, without a doubt the best work she released this year and, perhaps, her best body of work ever, features an astoundingly limited vocabulary, almost like a porn script was fed into an AI music bot: slut, dirty, tits, fuck, dick, throat goat, OnlyFans, etc. But that's really all you need — this is pop music at its basest and most purely fun, one of the few records this year to actually capture the ridiculous messiness of bloghouse classics, as opposed to just the aesthetic. It's ridiculous, stupid, horny — and perfectly Petras. — SD

12. Freddie Gibbs, $oul $old $eparately

After spending the past half-decade burnishing his boom bap bonafides via full albums with subterranean sample splitters Madlib and Alchemist, Freddie Gibbs proved equally adept at courting the mainstream on $oul $old $eparately. Adapting to a higher speed, higher fidelity aesthetic without breaking a sweat, Gibbs doubled down on the double time throughout $$$, merging the rapid-fire flows of midwestern rap antecedents like Do Or Die to the storytelling and lyrical focus he honed in the wordplay-centric underground. The guest list alone is stellar, equal parts trap heavyweights (Offset and Moneybagg Yo), rap superstars (Pusha T and Rick Ross), and cross-coastal veterans (Scarface and Raekwon), with every single feature living up to Gibbs’ impeccable standards. This curatorial prowess is all over $oul $old $eparately, a rare big-tent rap album able to satisfy discerning purists and casual listeners alike in 2022 and a well-deserved victory lap for an artist that has consistently defied expectations for over a decade. — SR

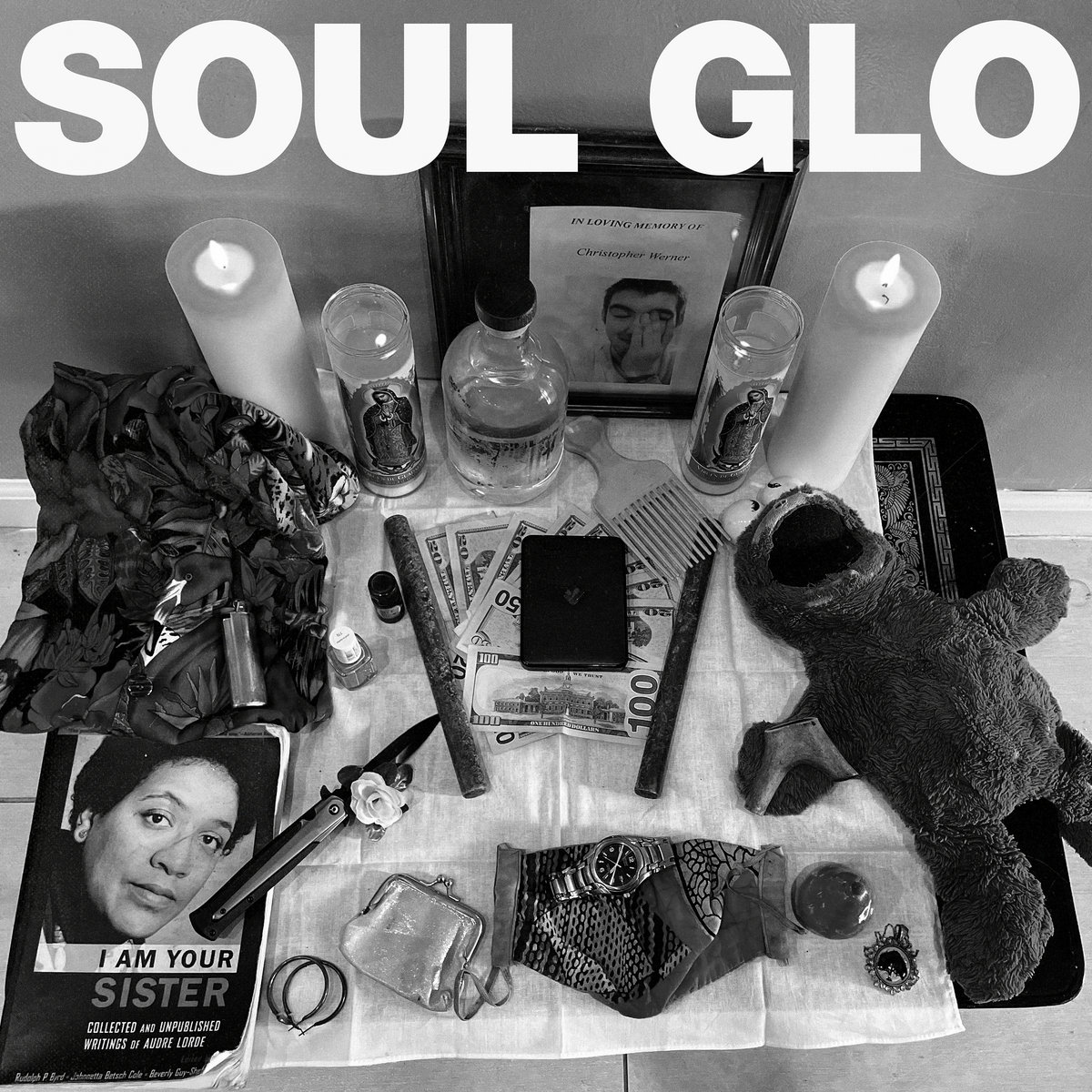

11. Soul Glo: Diaspora Problems

Running the gamut from a call for political uprising to a track about the ins and outs of upselling Yeezys on StockX, Diaspora Problems — Philly hardcore band Soul Glo’s fourth album — makes you want to drop everything and join them in their mission, whatever it may be. They look out across a landscape that simply isn’t built for a band of predominantly Black men to thrive (white drummer TJ Stevenson is the subject of some amusing mockery in their videos) and say “fuck this” as they take control. Vocalist Pierce Jordan sprays his words, rapping one moment, howling the next, catching targets including a healthcare system incapable of caring for the mentally ill, racism within the punk scene, and the temporary nature of Black success and wealth. He also turns his gaze inwards, writing starkly about the loss and depression that has informed his worldview. The soundtrack to Jordan’s machine-gun delivery is aggressive in a way that mirrors his urgency. Drums and guitars sprint throughout an album that can be overwhelming when taken whole but rewards repeat listens as new favorite lyrics (“Is it really possible for a n*gga to piss off his therapist?”) pop out before disappearing as the next wave of guitars hit. Like the rich yet troubled life it captures, Diaspora Problems is relentless like that. — DR

10. Molly Nilsson, Extreme

Molly Nilsson’s latest album feels like a true survey of our final days, the Berlin-based Swede reshaping her latently political power ballads into outright protest songs. On opening track "Absolute Power," she implores us to "get ready for the fight of the century": "Who we are versus who we'd like to be." That's kind of what Nilsson has always been about, but her past songs have been softly bittersweet, a track like "A Slice Of Lemon" from 2018’s 2020 layering images of a watery cocktail and a teary breakup and climate change into something collagistic and hazy. Extreme is, by contrast, hard and transparent with its intentions, and although "Absolute Power"'s haze of hair metal guitar may be a feint, Nilsson is still forceful with her words here. Not least on “Pompeii,” where she practically pleads with the listener not to spend their final days burdened by regret and pain: “How are you gonna spend your only life?” — SD

9. The Weeknd, Dawn FM

The Weeknd likes to kill himself. In the music video for 2015’s “Tell Your Friends,” Abel Tesfaye buried alive a plastic-wrapped version of himself from his debut studio album Kissland, which had been a critical and commercial dud. Two years later, finally the pop star so many thought he would become when he emerged, the venal crooner from downtown Toronto used the “Starboy” video to once again suffocate himself (this time before bashing his awards cabinet and mounted platinum records with a crucifix). Tesfaye made his life a spectacle, reaping the rewards and suffering the consequences. This year’s DAWN FM, The Weeknd’s best full-length project since House of Balloons, is his most compelling reckoning with his fate yet.

Dawn’s narrative, a cosmic pop radio block hosted by DJ Jim Carrey, is a spirit molecule-stretched excursion through a journey to the afterlife. “'Cause after the light,” Tesfaye wonders on the opening title track, his falsetto tremulous with vulnerability, “is it dark? Is it dark all alone?” Dawn FM is elevated into a sonic odyssey worthy of a pop star’s ego death by its co-executive producers: Oneohtrix Point Never’s ‘80s-tinged electronics shine and shudder in their own morse code while pop godhead Max Martin brings menacing disco to songs like “Take My Breath” and “Sacrifice.” These collaborators are just one facet of the album’s pool of ambition, seemingly endless and eager to truly gaze upon the face of infinity. — JD

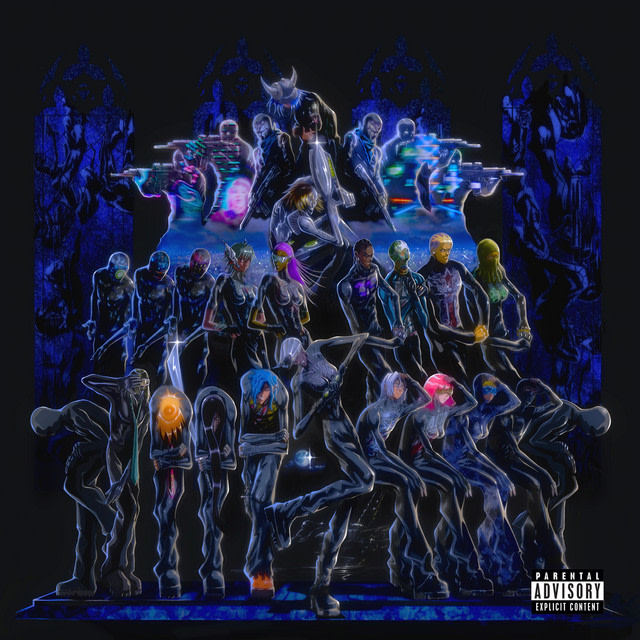

8. Cruel Santino, Subaru Boys: FINAL HEAVEN

Cruel Santino spent so much time watching anime and playing video games during the pandemic that he started to hear “gaming music” in his head. Subaru Boys: FINAL HEAVEN thus sounds like the opalescent soundtrack to a forgotten PlayStation 2 release. Inspired by the worldbuilding of Hideo Kojima, the Nigerian artist’s hour-long epic dives into the futuristic, underwater society of the Subaru Boys, a fictional group of agents who carry out top-secret tasks on behalf of the government. By playing loose with the concept, Santino acts more as a curator of mood, guiding listeners through the soothing (and occasionally explosive) world with irresistible melodies and charming style. An eclectic set of guests joins him on this quest, breezing through surf rock riffs, deep Afrobeats drum grooves, and 2000s R&B guitar loops. It’s almost like Cruel Santino has kaleidoscopes for eyes — in every song, you can hear a dozen shattered ideas being glued together into a beautiful arrangement of colored glass. — BC

7. Bad Bunny, Un Verano Sin Ti

Bad Bunny was already a phenomenon before Un Verano Sin Ti — the fanatical admiration for the Puerto Rican star ran deep even beyond Latin America. With his fourth solo album, he set a new bar for contemporary Latin pop, imbuing Caribbean and diasporic genres with unique concepts and experimental arrangements. Recorded on the neighboring islands of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, Un Verano Sin Ti is a 23-track reflection on Caribbean joy, incorporating genres like reggaetón, reggae, dembow, Dominican mambo, and bachata. Four of its standout tracks open the album including “Me Porto Bonito” a reggaeton number featuring Puerto Rican veteran Chencho Corleone, and “Titi Me Pregunto”, which netted him another Latin Grammy. The album’s first half revels in a celebratory and joyous tone, unpacking Bad Bunny’s poignant tug-of-war between relationship nostalgia and the liberation embedded in singlehood, while its second half leans into the sadboy vibes that have been a core part of his brand since X100pre, incorporating textures of dreampop and suffusing his endless summer with melancholy.

Elsewhere are some of Bad Bunny’s most stridently political songs yet. “El Apagon” (which translates to "The Blackout") serves as a critique of the privatization of Puerto Rico’s electrical grid and the community displacements occurring due to gentrification. The track opens with a loop of African drum, a symbol of protest, found in Ismael Rivera’s “Controversia”; later, it slides into electronics, sampling the phrase “me gusta la chocha de Puerto Rico” from DJ Joe’s “Vamos a Joder.” It’s a song that’s typical of Un Verano Sin Ti as a whole – an unapologetic narration of island life through the lens of a storyteller who’s healing, reflecting on, and embracing the cultures that raised him. — JM

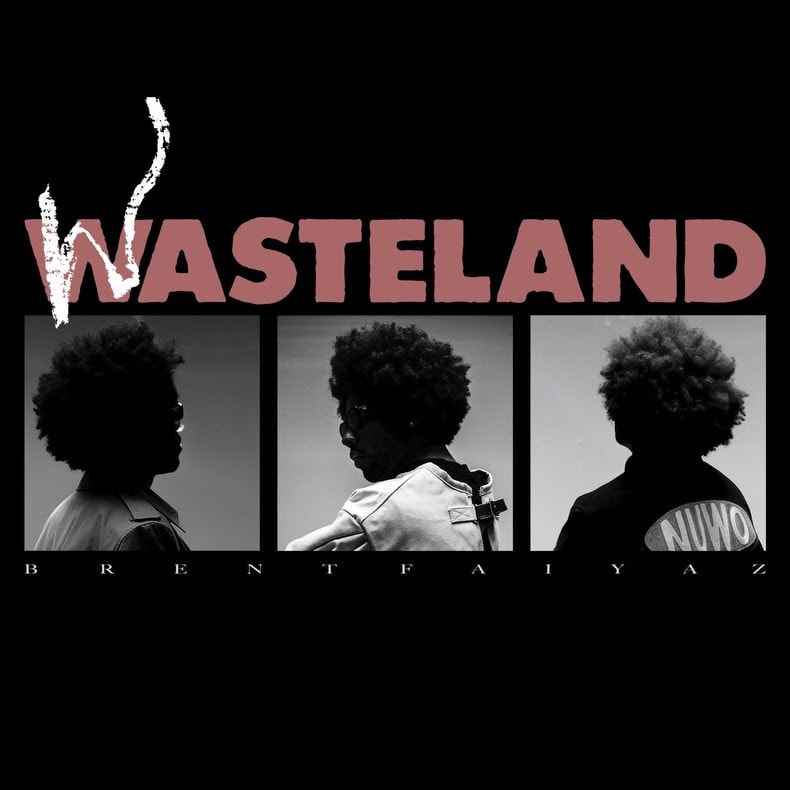

6. Brent Faiyaz, WASTELAND

“What purpose do vices serve in your life?” Jorja Smith asks at the end of the introduction to Brent Faiyaz’ second studio album WASTELAND. Faiyaz would probably be among the first to admit that self-indulgence — his greatest vice — gets him into more trouble than he’d like. In his songs, sex is treated like a game and deep connections are tossed aside for one-sided situationships. Since his arrival in the late 2010s, the Maryland singer has charted his own path, carving out a catalog of music that plays with expectations of trap soul and sleepy vibe-focused R&B with fine-tuned subversion and ambitious song-making. A song might not introduce percussion until halfway through its runtime when Brent’s already said most of what he has to say (“Dead Man Walking”), or a song will feel like a collection of hooks stitched together because they sounded seductive when placed back-to-back (“Jackie Brown”). It can feel like he’s slowly adjusting a set of dials, hoping that the subtle alterations of his music don’t go unnoticed.

WASTELAND, equally blunt and detached, plays out like an episode of a soap opera, its cataclysmic tone and lurid subject matter animated by maudlin skits, grandiose production, and a star-studded cast that finds itself trying to match (and sometimes neutralize) Brent’s hedonistic persona. Out of all its contributors though, it’s Raphael Saadiq, understanding that the ego-driven world Brent depicts isn’t without warmth, who ends up appearing in the album’s moments of transcendence. Take the frosted-over and wistful “Loose Change,” where Brent’s conscience flickers between vulnerability and close-guardedness in one of the album’s most striking performances of tormented emotion. His guilt is eating him alive. As the lights dim and strings fade away, you can still see a faint impression of him begging for forgiveness. WASTELAND isn’t a wake-up call or an intervention — it’s a self-conscious choice to live in the nightmare. — BC

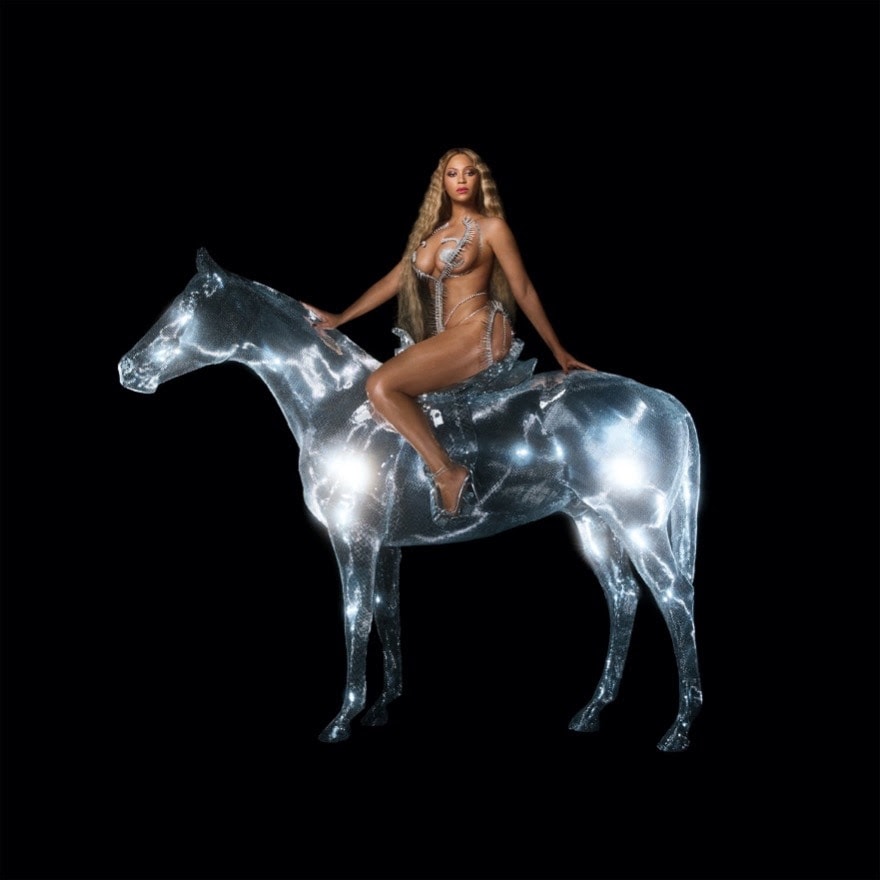

5. Beyoncé, Renaissance

Where Beyoncé goes, those who believe they can keep up follow. She’s spent the last decade shirking every prediction and expectation for her next move, ensuring that even when you think you have her figured out, you don’t. For Renaissance, her seventh studio album, there was no unannounced release in the dead of the night, nor was there an accompanying visual film premiered in tandem with its arrival. Presenting the music on its own, packed with a history lesson of epic proportions, Beyoncé served as a guiding force informing audiences of how this record in particular is meant to be consumed. It serves as a reminder of the power of her musicianship itself in the absence of an attention-diverting spectacle. Renaissance demands attentive listening.

The record doesn’t just reveal the inner workings of a vocal mastermind, it also offers a comprehensive understanding of the Black queer performers and artists who have carved out spaces for themselves for years through dance music, breeding innovation and excellence within their communities in the club and ballroom scenes. Beyoncé presents their world to a wide-spanning audience on Renaissance. The album ruminates on sex, pleasure, and a desire for escapism — it’s a presentation of hedonism and unshakable confidence in the face of resistance. “Cuff It” unites her audience through dance, whereas “Move” and “Alien Superstar” embrace an infectious sense of confidence. This, at its core, is a reflection of the functional purpose of dance music in Black and queer communities dating back decades. Beyoncé sees the widespread yearning for release that prevails even today, and ushers her audience through the door with welcoming arms. — LP

4. Sudan Archives, Natural Brown Prom Queen

On Athena, her debut album as Sudan Archives, Brittney Parks inhabited a sonic terrain that was expansive, majestic, and intriguing. The follow-up, Natural Brown Prom Queen, has the singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist (perhaps best known for her command of the violin) breathing life into a whole new world. She channels the poise of her earlier work, but into something that is bigger, more sumptuous, more candid, and more intricately experimental, yet simultaneously more pop-leaning. As she told the FADER this year: “Now I’m not afraid of the word [pop] because I just think it means you’re poppin’. And I am poppin’.” Parks taps an eclectic group of producers on NBPQ, including hip-hop legends like Hi-Tek (who shares her hometown of Cincinnati) and Nosaj Thing, British indietronica producer Orlando Higginbottom (Totally Enormous Extinct Dinosaurs), and UK rap mainstay JD. Reid. She fearlessly runs the gamut of genres and eras, gliding into her own future.

Ultimately, NBPQ is striking because Parks embraces abundance; no stone is left unturned. Her violin plucks through the air, syncopated and soaring; polished drums recall sleek R&B or else thumping, thotty trap; punches of brass and heady bass rattle around you. All the while, her voice bends and beams — sometimes in breathy, silky song, elsewhere in choppy bars. An album that deals with beauty, love, and sex, NBPQ is ecstatic but also deeply intimate and, well, horny (lyrical highlights include “Suck out the honey, I want you to fuck me” and “I just want the d-i-c-k”). Sudan Archives binds you tightly in her velvet rope — yes, the album deserves a Janet comparison — and lifts you up with her. — TJ

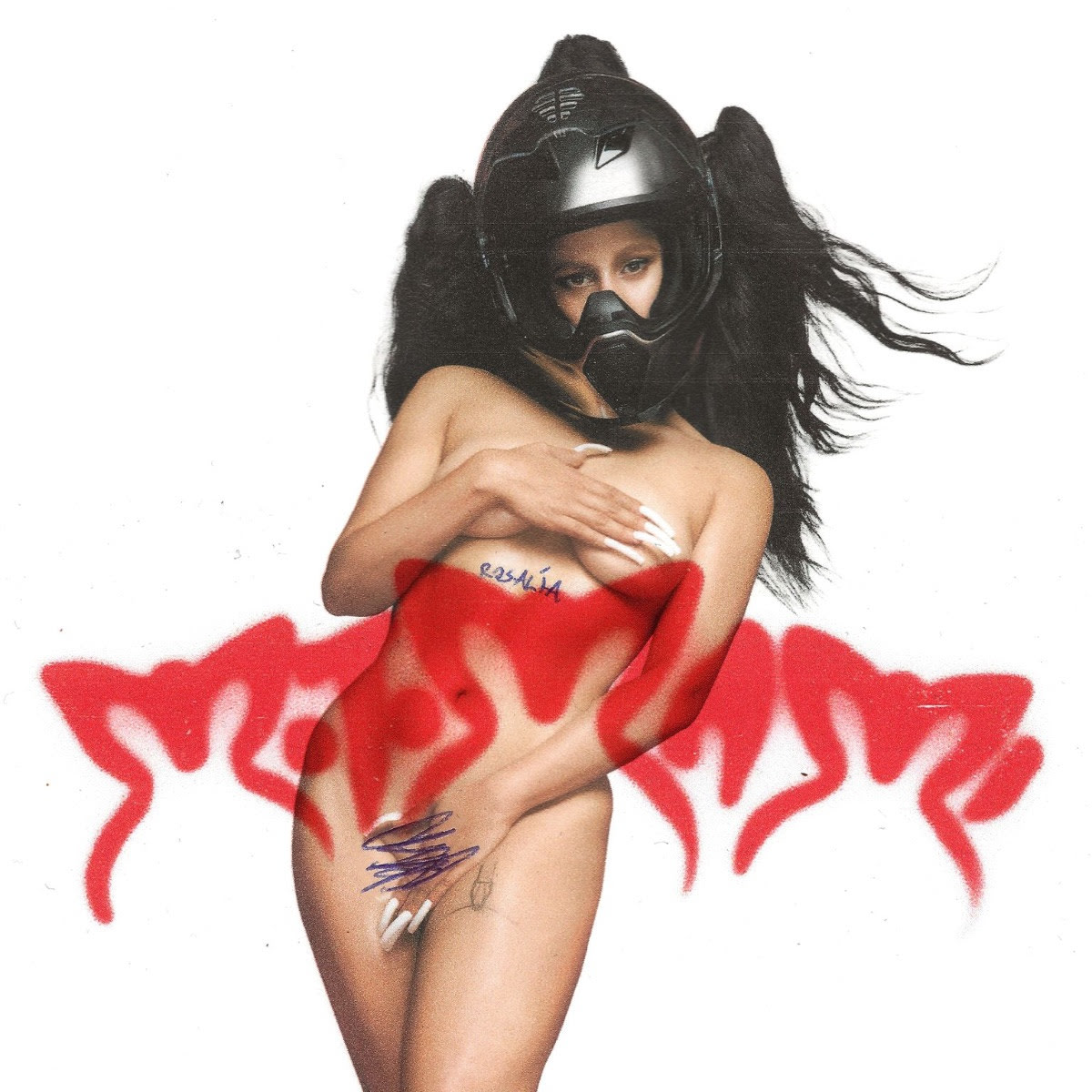

3. Rosalía, MOTOMAMI

Rosalía is one of music’s greatest living collagists: a textural auteur who appears to fold every sound and taste, culture, and country she’s ever experienced into her own extremely complicated and dynamic universe. While she established herself as a fusion artist on her previous two albums, deftly finding a space to innovate around flamenco traditions, on MOTOMAMI she treats every sound and every experience with equal importance, as though each is a vital part of her toolbox. She balances flamenco and bachata with reggaeton, dembow and bolero with samba and synthpop, and all with bewildering ease and virtuosity. It’s a masterpiece of contrasts, from the musical palettes through to the album’s themes: holding romantic attachment in one hand and total freedom in the other; it’s flooded with both excitement and hostility, sex and death, fame and anonymity, whimsy and severity, everything-ness and emptiness. While Rosalía is clearly the main character of the MOTOMAMI universe, her references and inspirations are also deeply studied and in plain sight. She sets this template up immediately with opener "Saoko," a bass-warbling redux of the 2004 Wisin and Daddy Yankee reggaeton classic “‘Saoco,” paying tribute to the masters over free-jazz percussion as she calls to them: “Saoko, papi, Saoko.” More than just an album, MOTOMAMI practically functions like a bibliography of musical sources as well as a light into the future. — EM

2. Alex G, God Save The Animals

There is a moment on “Immunity,” towards the back of Alex Giannascoli’s ninth album, when reality seems to shift. The piano that’s been looping blissfully for the past two minutes jolts into a new rhythm and key. It keeps reaching higher, dizzier the further it climbs into rarified air, as if Giannascoli is searching half-consciously for some beautiful new idea in real time. That sense of subliminal exploration animates God Save The Animals. Here Giannascoli sings through a fascinating and often oblique cast of characters, following their thoughts and mutating his voice as he goes. They want to talk about God, and Giannascoli is happy to explore that word, though he’s more interested in faith as a broad concept than he is in religion or its strictures. Maybe that’s why dogs are typically, though subtly, ever-present (“They hit you with the rolled-up magazine,” he laments on the glorious, driving “Runner”). And maybe that’s why, on the beautiful country song “Miracles,” his voice remains untouched when he sings about a faith beyond philosophy: “You say one day we should have a baby, well / God help me, I love you, I agree, yeah.” — ARR

1. Billy Woods: Aethiopes

Ideas, both good and evil, endure. The struggle for democracy in Rhodesia — the English colony in Africa that declared independence in 1965 to preserve white minority rule — animated the protests of both billy woods’ father, a writer and academic living in exile in the United States, and Thomas Mapfumo, a Shona artist who created Chimurenga (pop music targeting the Rhodesian state). Rhodesia dissolved in 1980 and became Zimbabwe, where Robert Mugabe was elected and unleashed a dictatorial rule (Mapfumo was forced to the United States for decades; woods’ family returned to Zimbabwe until woods’ father’s death in 1989). Rhodesia has disappeared, but its white supremacist principles stuck: years later, Dylan Roof photographed himself with the country’s flag before killing nine Black people in a South Carolina church.

Africa, its diaspora, and Blackness are all ideas as well, and on his masterful 10th solo album Aethiopes, New York rapper billy woods explores their origins, implications, and stories with impressionistic fervor. Produced by the New Orleans-born Preservation, who taps a litany of Ethiopian-origin samples, Aethiopes isn’t direct protest music like Mapfumo’s, though they share a common enemy in colonization and the Eurocentric definition of the continent. (“Aethiopes” is an ancient Roman term for people from Africa). Instead, woods engages in what he calls a “flattening of time.” Within each bar, he draws threads connecting vast oceans of time, fiction and non-fiction, and his own suffering with our broader malaise, all in a flow that never loses the urgency of a burning bush’s homily. Unflinching, rich, and surprisingly approachable, Aethiopes rises above its misery as it seeks to break the torturous wheel of the ideas that we mistake for human nature. — JD