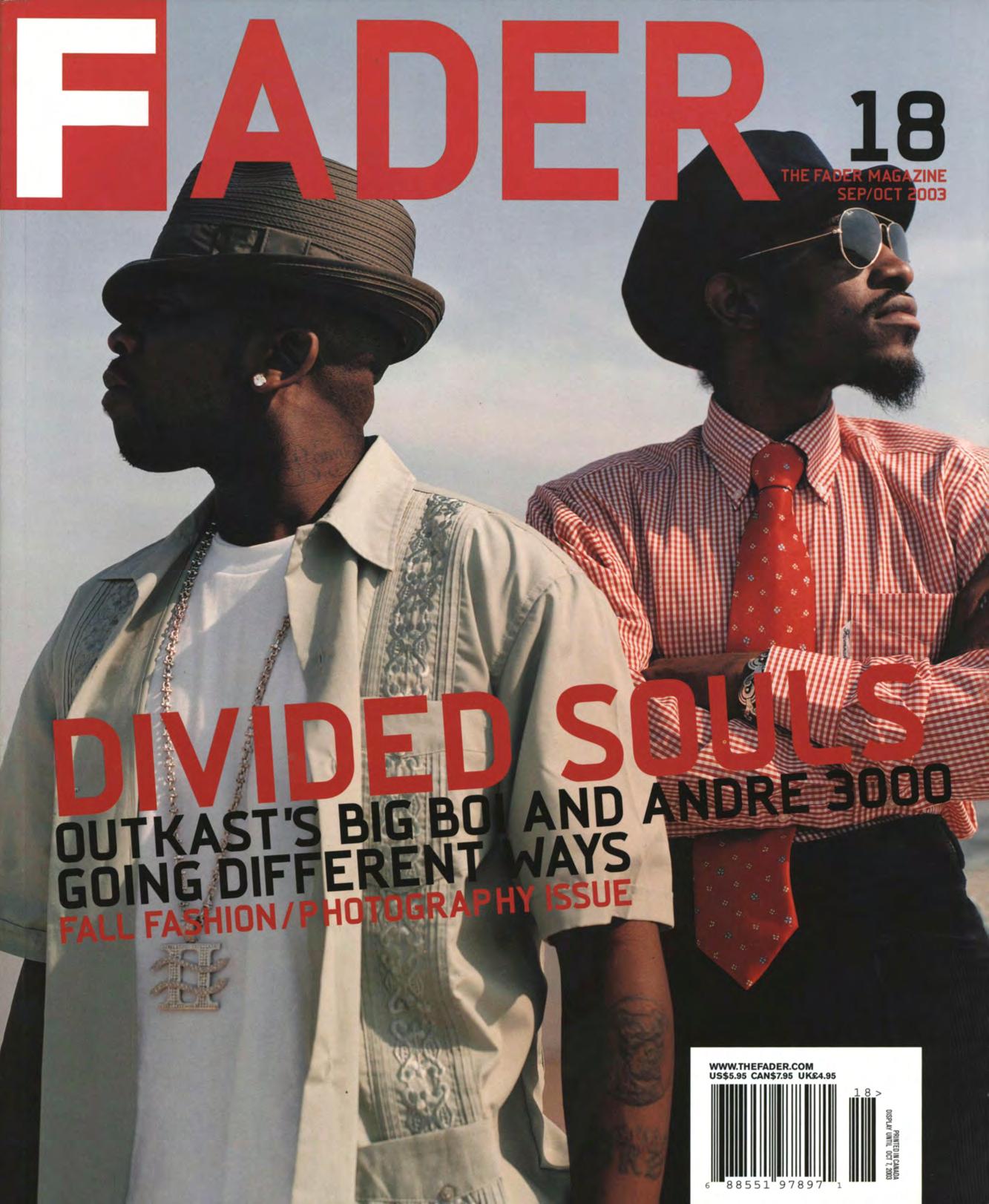

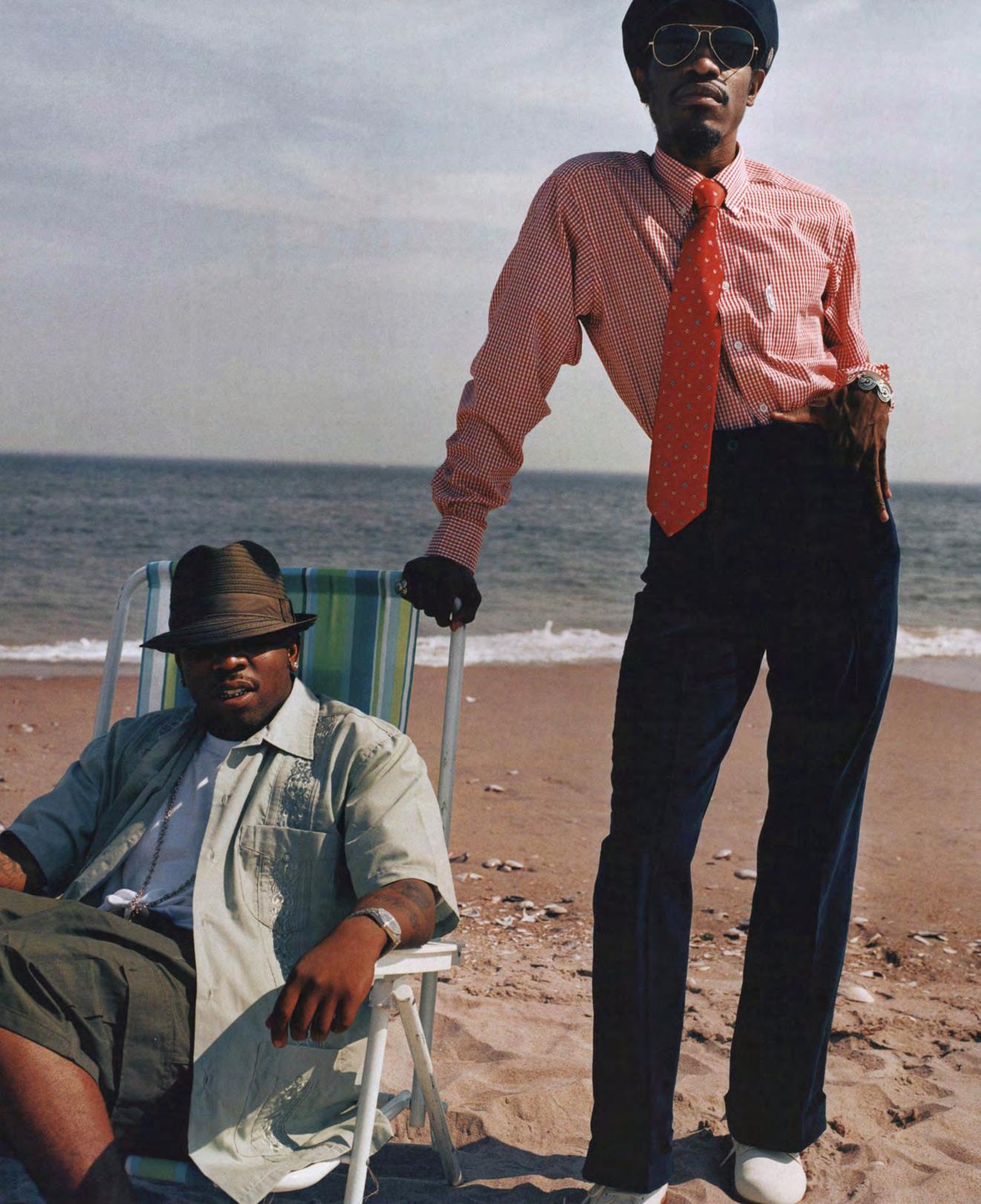

Picture two young black men from the depressed corners of the American South, friends since middle school and for life, who slept on apartment floors together, who got laughed at and then got rich and famous together, who now can (and do) laugh at others together, who have sometimes laughed at each other, even when it wasn't really that funny. Two men who never turned their back on each other but might've turned their side once or twice, two young men who’ve released six albums over the last decade, sold millions and millions of records and who are now admired around the world, by peers and fans alike.

Two “grown-ass men" now, as they each say, both with little children and the responsibilities of what middle America calls 'extended families,' now with more financial ventures in their name than one can count-the standard hip-hop-stability-and-opportunity-for-life-(well, maybe)-outlets that are the urban clothing company and the record label and the production companies, plus the dog-breeding and art-peddling and a fucking internet service that will give you not one but three email addresses ending in 'outkast.net' for $21.95 a month (plus customized Outkast desktop wallpaper for your PC or Mac).

For Big Boi and Andre, who are at any moment either young dudes still or grown-ass men, all that shit is necessary, to expand and secure their net worth, to support their families and their ideas, to foot the bill that will allow them to continue to make their original music. Ironic, though, that over time those extra seeds they planted have been siphoning off control to other places. Andre says, "Outkast Clothing—I think it makes money, but I don't even wear the clothes. I've never worn 'em, maybe once or twice. I don't like the clothes, really, and I think we could be doing better things, but at the same I see that Outkast Clothing is never gonna be more than just an urban clothing company."

Andre Benjamin and I met in January 2000. at a bookstore, nine months before the release of Stankonia. We have remained friends, close and not close at the same time, the way you sustain a friendship when suddenly both people have wildly different schedules; to be truthful, our friendship is almost completely unrelated to Outkast, leaving me with insight into Andre Benjamin the individual but not so much into Andre 3000, one half of the group. One of the first things he said to me when we met in late June of this year to talk about Speakerboxx/The Love Below, the Outkast double record soon to be released, was, “You know how it is right before an album comes out— it's good and it's bad. Mostly bad, though, this time around, at least for the fans. I think I'm ready to quit "

Awww, shit is what ran through my mind, and a little bit of Not that again. Well, what's changed? I asked. Your fan base has expanded crazily! "That was all MTV," he said quietly. "MTV played a big part in all of that. Once you're on TRL, all of a sudden you're a household name." This from a man who along with his partner is responsible for introducing the world to Atlanta. Georgia, a city that until very recently still flew a Confederate flag at its capitol. Throughout the day, he kept using the word entartainer. "I'm talking about being an entertainer. All the stuff you have to do, all the meetin' and greetin' people and being friendly and being, you know, chipper and all that type of shit. There's nothing wrong with that, but I've just never fit into that. I realized, Hey, I don't like this and this is not healthy for me. "I've gotten way too critical of my own work," he says later. “I end up not liking anything. [It comes from] always looking for the best you can do. And I'm thinking the best that I can do is not [Outkast]."

The MTV generation has affected Big Boi's personal universe too. "I was buying my son a bird last weekend, at this redneck flea market in South Atlanta. The peole in there were cool, they were real nice, and I picked out a bird. I said, 'Okay, I'ma get this bird right here, so could you pack it up for me? I'll be back! I come back, and the bird is still in the cage. I guess they thought I was bullshitting. Then a bunch of 12 year-old white girls, a cheerloading troop, came over [to me], screaming and asking for autographs, So now the lady wanted to school me about where the birds came from, how they was born... Little shit like that lets you know [we] still ain't shit."

The Vanity Fair editor that comes to the meet-and-greet before their big Music Issue cover photo shoot wants to make sure Big Boi knows he has the OK to smoke at the shoot, wooing them with stories of Willie Nelson's penchant for weed and her years touring with Led Zeppelin (Zeppelin's music had a very strong presence during the recording of Outkast's second album, ATLiens). Then, regarding Queen Latifah, who'd also scheduled to appear in the photograph, she says something like "What do I call her? Do I call her Queen? Do I call her Latifah?" (Big Boi says, “Call her Lala' “Really?!" “Oh, I don't know" he answers. It has also been requested for Andre to please wear his hair out.

So maybe Outkast is over. The MTV generation may miss the easy accessibility of Andre 3000's psychedelic/funkadelic outfits and Big Boi's pimpster ways being brought to them as a package, but with both Andre and Big Boi as fiercely committed to their work as ever, the future of black music isn't looking so bad.

Both men have always focused on contribution, surveying what’s missing in music at a particular time and creating something to fill that void. The two men have worked separately on their music for years now-many people might be surprised to learn that Big Boi and Andre recorded most of Stankonia at separate times, often times not crossing paths for days, even weeks. Knowing this, the concept of a double album with each contributing their own separate disc (they do, of course, appear on each other’s, and both men produced music for both albums as well) presents them with the opportunity to continue to explore the things that are important to them now.

For Andre, it's a return to feeling, to emotion—things best evidenced in the R&B and black popular music of the late '60s and '70s, early '80s, even. This real rhythm and blues was brought to life and to music by the vulnerability of the hardest cats—Harold Melvin and the Bluenotes, Bobby Womack, and later, Prince—men who recogized and embraced the power of beauty and the importance of, well, true love. Andre's disc, The Love Below, is, according to him, about "relationships and love and hating love." Granted, some of the music featured on his album was initially intended for a film about falling in love in Paris that he developed in late 2001, but he doesn't disagree when I suggest that women have been a central theme of his work for several years now. ([“After you become successful] you get all these different women. But at the same time, you don't really have nothin," he laughs.) The first solo song of his he ever played for me was called "Nostalgia"; I heard it in early 2000, and all I remember of it was one line that Andre sang over and over in a high falsetto: You make me feel likee 10th grade lunch. Then there was “Miss Telescope", who is looking for a star/ But I'm just a comet. These are three-year old songs, but it seems the subject matter of much of Andre's work hasn’t changed that much in all this time. At press time, only a handful of songs for The Love Below were finished, and according to him, the overwhelming majority will feature him singing only, not rapping. Anthony Middleton, who has worked with Outkaat in one capacity or another since Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, the group's first album, says, "It's almost like the stars have to be aligned in a certain way for him to write."

Yes, he can be precious at times—"He needs that acceptance from the masses," says Big Boi— but it's not an overstatement to say that he is enormously talented as a musician. I once heard a piano-based composition he wrote called “Blueberry Mansions" that would make a grown man cry. One of his priorities at the moment is to discipline himself enough to perfect the guitar, which he’s been studying for a few years, and the saxophone, which he recently picked up. Even

Big Boi calls him “a musical genius” (though he later adds, ”Dre used to always talk about the fear of tailing off. I don't even think about that shit. All I think is, I wonder what the next one will sound like").

Big Boi’s heros and influences are those strong black men of decades past who refused to compromise or sacrifice their music or their manhood—James Brown, Gil Scott Heron, Sly Stone, the likes of which have rarely been spotted in popular music since then, certainly not in the hip-hop “game” he so often refers to. "For Speakerboxx, I canvassed 1968 to 1973," he says. Everything on his disc reflects this—seething, informed critiques of the US government, like you'll hear on "Tic Tic Boom", which features a pretty Indian chant but then unfolds into a long, furious verse condemning the recent war in the Middle East—in all honesty, a huge leap for Big Boi, the type of rap song that makes it inevitable to rewind just because he’s rapping so fucking hard you need to catch every single word. Then there are the unapologetic sexual politics of "Rooster", a song that, thematicaliy, could almost follow "Ms Jackson" (this time he speaks directly to his wife instead of his mother-in-law), where he raps You're on my team/ Starting first-string/ So why are we arguing?; the straight-up funk of "Bowtie," all big horns and Don't jive me, sucka refrain that makes it a song that would have worked just as easily on the soundtrack to Uptown Saturday Night. "That was the feeling I was looking for," he says. "The music was full, it didn't have one specific direction, it wasn't structured [where] you have an intro, you go into a hook, you got another verse, you go into a bridge, and then you out—you could do anything you wanted to. I was looking for funk."

Esquire recently quoted him as saying he'd also been listening to a lot of Ray Charles lately, a man widely credited with infusing the secular music of the '50s and '60s with a strong gospel constitution. Makes sense, then, that besides being supremely funky, Speakerboxx is full of power and frenetic energy that is at times tempered with thoughtful, reflective and melancholy undertones.

In hip-hop’s current "relaxed rappin'" climate, as Big Boi calls it, addressing current events is not the norm. “A lot of people today play dumb. I'ma make me a song called "Everybody Play Dumb," he says. "If you got the whole fucking world as your forum, you can talk about more than just tennis shoes and jewelry. My mic touches so many ears that l'ma say something. Fuck that. I'm not gonna be quiet."

After ten exciting, fruitful years, it would be inaccurate to say Big Boi is unaffected by what looks to be Andre's withdrawal from Outkast, especially if it's coming at a moment when he is more confident of his own work than ever. "He don't wanna rhyme? Cool, I'll do it for the both of us," he stresses. “He don't have to rhyme if he don't want to, 'cause I got this over here."

Speakerboxx has been ready for release for months now; Big Boi's impatience has been growing steadily over that time. For his part, Andre says, "Big Boi gets tired of waitin', I get tired of compromising.” So where does this leave Outkast? The third, unmentioned side of the unselfish 'compromise-respect' triangle Big Boi credits with making Outkast speciel is 'sacrifice.' The word never comes up in my convorsations with either men. There's no love lost on either side; and though both men admit their friendship has been challenged by their success, they are as loyal and protective of one another now as they must have been in the beginning. Still, the sacrifices they have each made are catching up to them.

Ironically, by being half of Outkast, Big Boi has sacrificed the very refusal to sacrifice and compromise that his idols seared onto their audiences, along with his competitive momentum; by partnering with Big Boi, Andre has had to sacrifice his vulnerability, the cloak of solitude that he wraps around himself in order to work at his own pace. With this separation comes a sense of freedom that might propel each man and his music to places even they didn't know they could go.