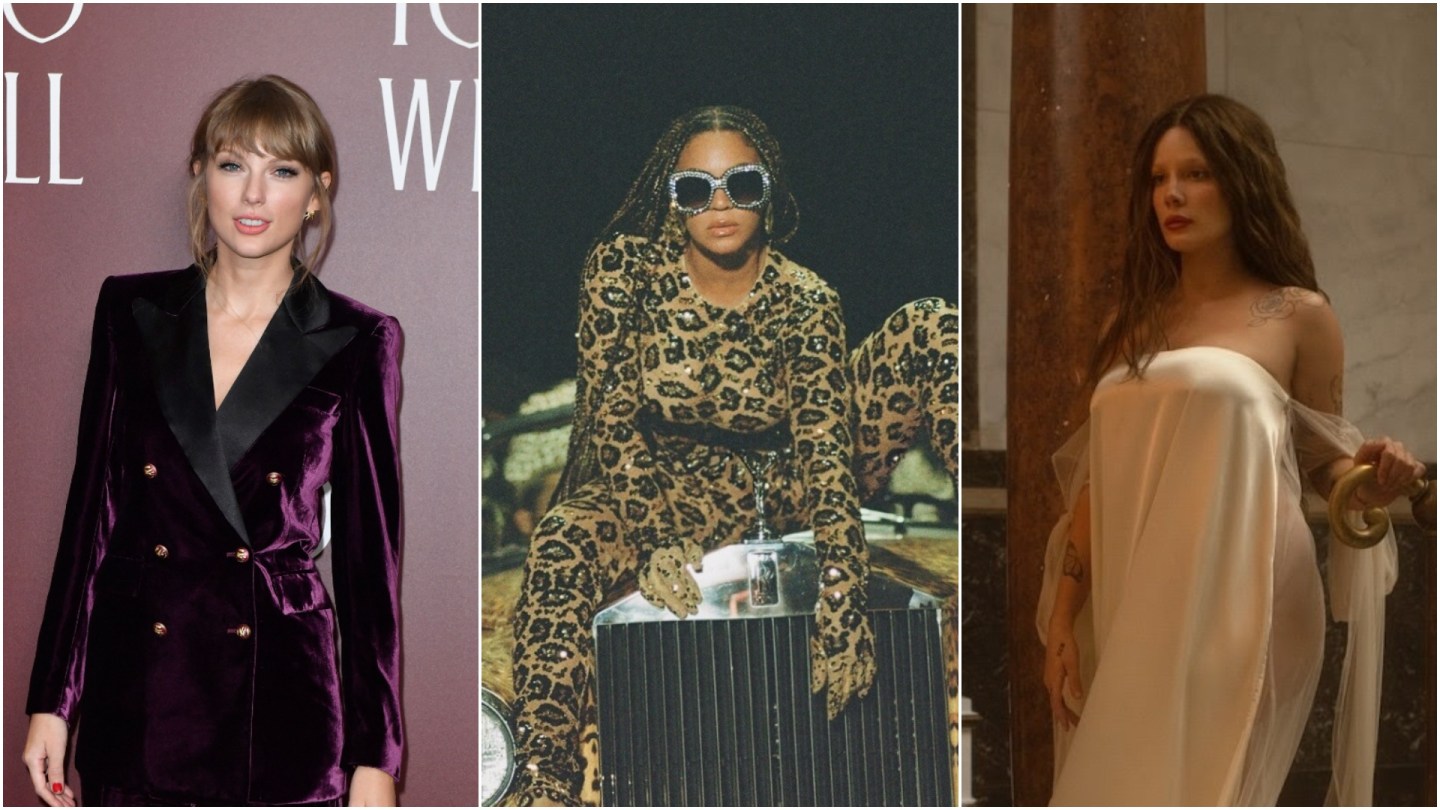

L: Angela Weiss / Getty Images | C: Travis Matthews via Disney | R: Lucas Garrido via Universal

L: Angela Weiss / Getty Images | C: Travis Matthews via Disney | R: Lucas Garrido via Universal

There was Beyoncé, stationed on the roof of a sinking New Orleans Police Department vehicle, surrounded by water; flashing lights from various sources, some more chilling than others; the Southern Gothic aesthetic of an old plantation. The visual for “Formation” clocked in at under five minutes and was quickly regarded by many as the greatest music video of all time. What came after, the full-length film and visual album Lemonade (2016), further cemented Beyoncé as a once-in-a-lifetime artist. But she had set the standard for visual films in modern pop music long before.

In 2007, she shared the B’Day Anthology Video Album, a collection of 13 music videos, seven of which she directed herself, which laid the groundwork for her 2013 surprise release, Beyoncé, another complete collection of music videos that guided the music (and vice-versa). But where those two releases were loosely threaded together by musical concepts, Lemonade and 2020's Black Is King were sonic and visual events. The narrative and cinematography were both rich, and the socio-political commentary threaded throughout the films ensured that they’d still be studied years later. Maybe they lit a fire under her peers to do something similar.

In the same year that Beyoncé arrived in the dead of the night, Fall Out Boy released the 13-part Save Rock & Roll music video series The Youngblood Chronicles. In the years since, we’ve had musical films and collections from Janelle Monae, Frank Ocean, Troye Sivan, and loads more. That in itself is nothing new; storytelling and theatrics have always been central to pop music –– think Michael Jackson’s 13-minute music video for “Thriller” and the short film anthology of Moonwalker, or Prince’s Purple Rain –– but it’s become increasingly clear that we’re living through a new Golden Age of pop music cinematography. Cohesive, thought-provoking visual collections presented in increasingly non-traditional formats have come to make average music videos look like child’s play. And while some of these recent visual companion pieces are more intricately planned and executed than others, when done well they can make room for engaging conversations. They should be examined as complimentary works of art.

At the time of writing, Taylor Swift is a few hours away from sharing All Too Well: The Short Film, a visual extension of the already extended 10-minute long deep cut “All Too Well” from Red (Taylor’s Version), directed and written by Swift herself. She’ll also star alongside the underrated Dylan O’Brien (Teen Wolf, Love and Monsters) and Stranger Things star Sadie Sink. Swift has always been a gifted storyteller, lyrically and visually; she’s directed her own loosely narrative-driven music videos, including “ME!” and “Willow.” But there’s a difference between a five-minute music video, which seeks to lay out a creative vision adjacent to a song, and a 10-minute visual journey derived from — and expanding upon — the artist’s own lyrics.

The film’s poster and Swift’s ever-speculative fans suggest a possible commentary on the age gap between the singer and Red (Taylor’s Version)'s chief antagonist, Jake Gyllenhaal. “And I was never good at telling jokes, but the punch line goes / I'll get older, but your lovers stay my age,” she sings in a scathing new verse on the song. The singer we hear here is aided by the clarity of a decade of growing up and the realization that it was more than just a breakup. To add to the narrative of the album nearly a decade after its release not only with an extended version of the song (and the eight previously unreleased additions from the vault), but also an entirely new visual component is an exercise in creative repurposing worthy of dissection.

Visualized musical projects are understandably approached through a different critical lens than if they were to have been written and scored as a traditional, full-length film. (That is, if they approach them at all; coverage of the music itself greatly outweighs that of the visual component.) Halsey’s attention-demanding If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power so carefully straddled the line of that binary, it set what should be a new standard of ambition for the genre. Directed by Colin Tilley, the hour-long film was released in select IMAX theaters in August, two days before the record of the same name arrived to streaming services, and offered chunks and snippets of all but four of the album’s tracks. Where the music was an exploration of the singer’s experience with pregnancy and childbirth, their performance in the self-written film experience took the route of social commentary on sexuality and birth. It didn’t present itself as a film set to music, or a cluster of music videos. Instead, the sparsely-scripted movie held its own alongside the music as a separate creative project.

The film and music are most allowed to work as connected vessels of storytelling when the artist manages to detach themselves from the constraints of their own artistry. The moment when they submerge themselves so deep into a performance that it feels as though you’re watching them portray a character rather than the pop star persona they’re known for, they strike gold. Kacey Musgraves recently starred in her own film, too, playing the lead in the work said to be “inspired by” her divorce album star-crossed, its title a nod to the tragedy of Romeo & Juliet, which also inspired the opening and overall three-act arc of the movie. The film is entirely cohesive — the screen doesn't fade to black after each song — building a solid narrative of a scorned divorcee as she journeys through healing. But even as other characters are introduced, the country star never fully commits to playing a role outside of herself, delivering almost the entirety of the album while making direct eye contact with the camera. The film’s transition points weave themselves together as tightly as they can manage, but it never manages to shake that extra long music video feeling throughout its 48-minute run time.

Machine Gun Kelly’s musical film Downfalls High is plagued by the same inability to establish a fourth wall, though it does come infuriatingly close. The scripted movie attempts to spin a meaningful narrative, with Euphoria’s Sydney Sweeney and TikTok’s Chase Hudson cast as two high school students bonded for life, but the connection unravels whenever MGK suddenly reappears and transports the viewer out of the scene they had just put so much effort into building. The disjointed progression makes it hard to view the script and structure of the film itself as anything other than supplemental to a half-baked visual album concept. There’s a better story to be imagined within the album on its own –– one that taps into the emotional depth the singer won listeners over with before using it as the soundtrack to a high school love story that ultimately trivializes its subject matter.

This isn’t to say that musicians shouldn’t venture into the world of long-form visual works if they aren’t skilled or trained as actors, writers, or directors. Quality can always be outsourced to creative partnerships, especially when the allocated budget allows for big-hitter recruitments to bring it to life. And there are levels of distinction lended to these visual releases, though the area still largely lacks the framework or vocabulary to meaningfully discern between its various forms. It’s a game of technical wordplay, more than anything: A music video versus a short film or, within that, a music video versus an album visualizer — like the video game-like graphics Lil Nas X shared for each non-single track on MONTERO.

An artist’s commitment to telling a story steeped in meaningful substance and themes is what makes these visual counterparts worthy spending enough time with to analyze as an independent piece of art. Without that, what results is just a glorified music video.