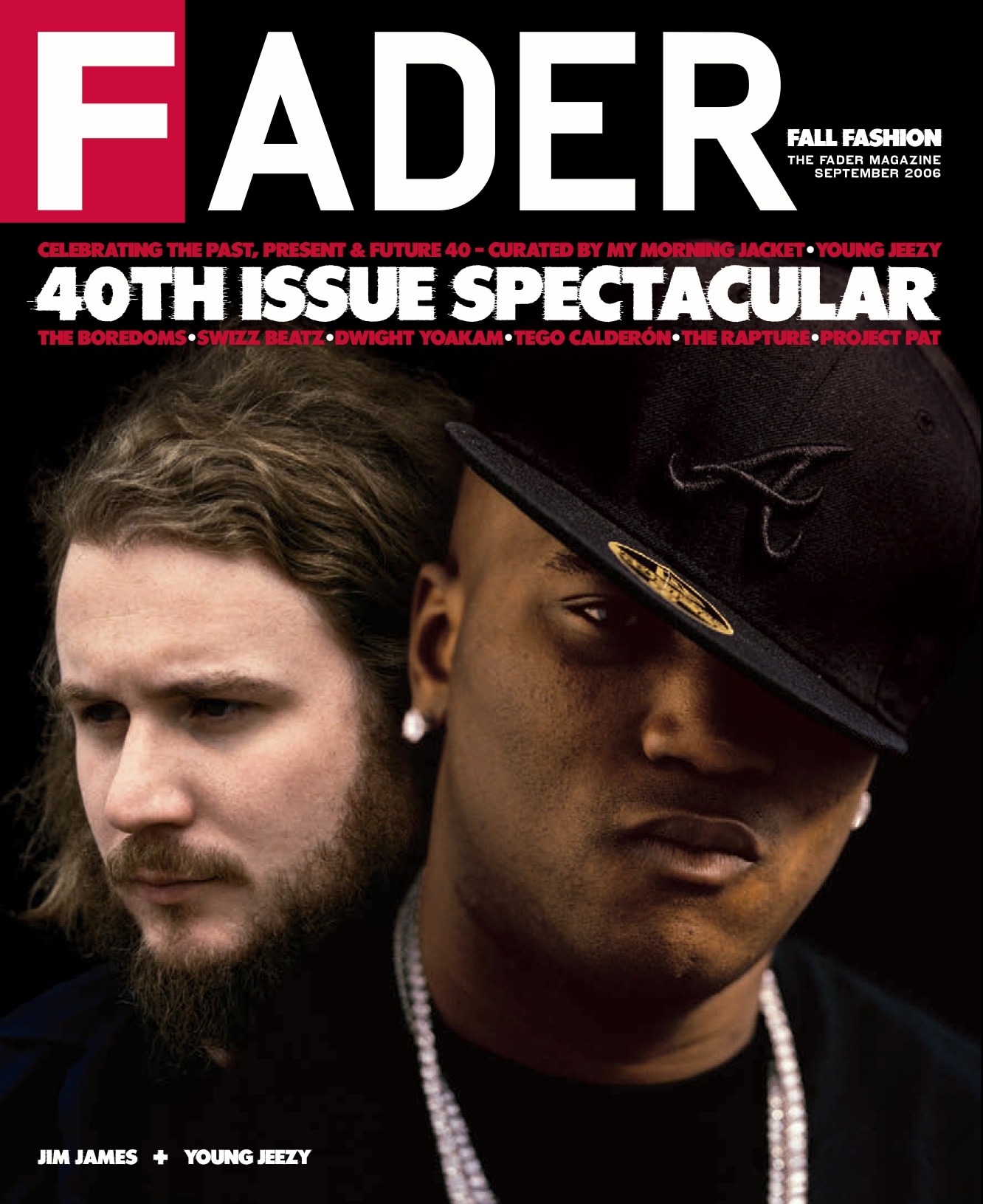

This week, I'm in conversation with Jim James of My Morning Jacket. Jim appeared on the FADER cover way back in 2006 as part of the 40th issue celebration. He had just overcome a series of very real setbacks, both industry and personal, and was transforming his group into one of the most exciting live rock bands around. Fans of the band's southern fried rock sound as captured on their breakout albums, It Still Moves and 2005's Z, were won over by a group unafraid to get weird. By factoring in all their influences from the world of classic soul, vintage R&B and psychedelia, My Morning Jacket were pushing the idea of what an arena size rock band could look and sound like.

Around the same time, 2005, I had a Friday night slot on East Village Radio, a very loosely run, but quality internet station that operated out of a storefront on 2nd Street and Avenue A in New York City. I played mostly hip-hop, funk and random things I was producing and very little else. I was almost oblivious to anything going on outside those genres. But Will Welch, who hosted the FADER's own radio show in the time slot right before mine, he would always tell me I had to check out My Morning Jacket because I would love how soulful Jim James was. In fact, I would hear that from countless people around this time. And when I finally checked it out, I understood exactly what they were talking about.

He has an incredibly soulful voice. He's an incredibly soulful individual. He's also incredibly earnest, forthright, spiritual, and overwhelmingly positive about the human race. You can feel his light instantly and his childlike enthusiasm. The minute he touches on something that moves him, be it the Muppets, Alice Coltrane or transcendental meditation.

A lot has changed since 2006, but My Morning Jacket have held strong releasing great albums, like the Grammy nominated Evil Urges as well as Circuital and The Waterfall one and two. This week, My Morning Jacket releases its ninth studio album. Jim has described the self-titled project as being about breaking people out of their reliance on the endless scroll of social media, Netflix binges, and yelling at people that you will never meet in person, while also managing not to sound like he's judging anyone for doing so. He really just wants to gently encourage us to occasionally go outside and bask in the glory of nature and be overwhelmed by love in the spirit. Sounds very appealing to me.

Mark Ronson: Where are you?

Jim James: I'm in Kentucky.

That's where you live?

Yeah. Well, I split my time between LA and Louisville. Where are you?

I'm in upstate New York.

Oh, cool.

Have you ever spent any time here?

Yeah, we made a record up there years ago, like 2004 at the studio that used to be called Allaire. Have you been to that place?

I know it's a really well known, very well regarded, like a lot of great... Dylan. Who made stuff there?

God, I don't know. I mean, there was a period there where, yeah, it was really popping off. But then I think the guy lost it in a divorce settlement or something.

Okay. Right.

So I don't know if anybody else has turned it back into a studio or not.

There used to be so many great studios. I mean, obviously because of Woodstock and the gravitational pull that had, there were obviously studios, Bearsville. Allaire was more upstate. But it's a shame because these studios with these great histories and heritages that you kind of just want to go at least once and plug something in or record something just to see what they did or just because they are special places there. There's very few of those. You've done records in some pretty extraordinary places. The last record, Waterfall, you did at the top of a mountain, I kind of read. What was that place like?

That place is called Panoramic. It's in Stinson Beach. Have you ever been there? It's like an hour north of San Francisco near Muir Woods. It's unbelievable. The studio is in this weird old house that this guy built ages ago and then they just kind of turned it into a studio. But you sit on top of this mountain and look at the curve of the bay is like half a circle. It's this really beautiful, really magical beach.

And where did you make this past record? I've only heard the first single, which is great, but this record that's about to come out, where'd you do that?

We did that at 64Sound in LA. Have you been there?

Uh-uh (negative).

Oh, it's great. It's a studio in Highland Park. The guy that runs it now, Pierre, was looking for studio spaces and he saw this big square building that he just went and found the owner to ask if he could build a studio in there, because it was just kind of a big empty square. And the owner was like, "Well, actually there is a studio in here."

Wow.

He built a studio in the seventies and had just been storing car parts and stuff inside there. But the whole thing was completely untouched, the board, the tape machine. And it's just got that real homey kind of 70s feeling in there. Really, really sweet place.

Do you have a studio in the house, in your place?

Yeah. Yeah. I record a lot at home. That's kind of what I do every day when I'm not on tour.

Is that how you know you're going the difference between demoing and making the real album? How important is it to go into those real kind of big studios when you could probably do something pretty great and realized at home?

Somebody gave me some great advice years ago to not demo anymore.

Right.

Because I don't know if you know that feeling, but it's like a lot of times you get trapped in the magic of the demo and you can never recreate it or whatever.

Yes.

Since I've learned how to engineer and record and operate Pro Tools and tape machine stuff, I just try to start recording for real. Then sometimes that real recording will become the foundation on which other stuff is laid or whatever.

Yeah.

For my solo projects, a lot of it is construction and stuff that I do by myself at home. But for My Morning Jacket records, one thing we really need is a big enough room for us all to spread out in and play live together in. So that's when the studios are really fun going to different studios. We don't even need a giant space. Like 64Sound isn't a huge space. It's just big enough for about five people to kind of get together in. That's one fun thing I think for me about making records too is just going to a different space each time and you just get the different of the room. I really love that. But it doesn't matter to me if it's a super pedigreed, Capitol Studios or if it's just somebody's living room or whatever.

Yeah. I'm sure, you talk about it a lot being so fascinated with sounds and especially just how did so many brilliant recordings from the late 60s and 70s were so few mics and why do they sound so good? One of the things that I watch over and over again, especially if I'm sort of wasted, or I used to, is the King Harvest live, the band, when they're just playing in that room of the barn.

Yeah.

Or watching the Questlove documentary. I don't know if you've seen Summer Of Soul yet, but Stevie Wonder, the drum sound, one mic and you're like, "This is the greatest sound." Like you said, there's just this voodoo in rooms. It could just be a room that's just a room in someone's house and it just has the magic way that the walls and the symmetry and the people playing. But...

You know what, there's something I think about too that is really fascinating to me. The air and the spirit of the time too because a lot of times you'll get people, I'm sure you've had this experience a lot, you'll get the room, you'll get the mic, you'll get the amp or whatever. You'll literally get your hands on all of the classic things. You'll get the tape machine or whatever that they use, here or there, but you still cannot recreate the air of that moment of your favorite recording. You can't capture the feeling of being in Motown or the feeling of being on that stage with Stevie Wonder or whatever. That's the thing that I think is so funny about the quest for gear and the quest for all that stuff because it's like people are searching for 'got to find that sound, got to find that Motown drum sound' or whatever. And you just can never replicate the spirit of the time and the air in the room.

No, absolutely. I heard a really interesting theory that people talk about Motown sounding a certain way and then Hi Records and Willie Mitchell with Al Green sounding a certain way because it was hotter. It was hotter in the room and it changed something, a way about the recording sounds and the tape, and Detroit was a colder place obviously a lot of the time. Have you ever thought about that, about the actual climate of the places that people are recording?

God, all the time. Well, yeah. It's so interesting because I've been to Motown several times on the tour and then we got to go record horns with Willie Mitchell for our third record before he died. So we got to go to Hi Studios. And when you're in Hi Studios, it's like covered in green foam and it's hot and steamy in there. Yeah. And Motown's a little cooler and it's in Detroit. I've thought about that a lot. We've made records in spaces that weren't well heated or air condition. So we made this one record in this giant gymnasium and half of that we did in the summertime with no AC and it was just so sweaty, so humid. And then the other half we did in the winter when it was cold and they sound completely different.

Really?

Just the air sounded completely different. Yeah. Because the water molecules and the humidity affect the sound waves are hitting all that water in the air when there's no humidity, they go differently.

Yeah.

It's wild.

I remember the first time that we went into Royal Studios, the Willie Mitchell place, and this was after Willie Mitchell had died and his son Boo was still running it.

Yeah.

We were just doing like a little pilgrimage almost to visit all these spots and driving up from New Orleans up to Chicago and stopping at all these places we wanted to see. And we really went into Royal as a bit of a tour. Like, "Okay guys, we got an hour here." And we just walked in and I looked at my friend, Jeff Bhasker who was producing the record with me, and I was like, "Cancel everything. We're staying here for the next week." Because it's like you said, you walk in and it's exposed beams. It's asbestos. You might be breathing in something unhealthy. You're not sure. But it was so obvious to me the minute that we went into that room, I was like, "This is hallowed ground and that I feel something here. We should stay here and just roll with it."

Oh yeah.

When you're talking about sounds and going to big rooms and stuff, I guess this might be a oversimplification. I hope it's not offensive. But I feel like with Jim James and solo records, it's kind of the drums because my whole shit is so drum-centric. I mean, sometimes it gets in my way, but sometimes I can listen to a record, I've spoken to this with people like Brian Burton, Danger Mouse, or Kevin Parker, and I can listen to somebody's album tell by the drums if we're going to be friends or not, or at least get on and talk about music. And I feel like with your records, the drums on the solo stuff is quite low, fine, really tight and kind of almost breakbeat-y. Then on the My Morning Jacket stuff, it's quite big and expansive because it needs that and you know live, it's going to feel that way and it's going to be swimming around these festivals. Does that hold any ground or is that offensive?

No, it's not offensive at all. Every record's so different, whether it's a solo record or a Jacket record. But it's funny, because I've known both of those drummers since fourth grade. My friend Dave Gibbon plays drums in my solo projects and then Patrick Hallahan plays drums for My Morning Jacket. I met both of those guys in the fourth grade. So I've known them both for over 40 years. So we have this really crazy thing. So there's never a set intention. Like a lot of my solo record drums, I just record them myself in my basement. You know what I mean? Jacket records have been all over the place from super crazy expensive studios to gymnasium to my basement or whatever. There's lots. I think it's just interesting because I think both of those guys play really differently. I think a lot of it's mostly in their playing, but I always just try to follow the energy of the song and the moment. So there's not a whole lot of conscious intention.

Can you tell me about making this record? I feel a little bit like an idiot asking about it too much, because obviously I've only heard the first single, but what was the process? Was it any different from other records that you've made?

Yeah, it was really different because we didn't really know if we were going to make another record. I'd kind of had had to walk away from the band for a while because I was just burnt out on it and burnt out on touring and didn't really know. I couldn't really figure out if I was just over it all in general or if I was just too burnt from doing too much.

Yeah.

So we ended up playing some shows together and realizing that we still enjoyed playing together. So we decided to go into the studio. But one thing that was really different this time was that there was nobody else in the studio. I did all the engineering and recording and stuff. So there was literally just the five of us. In that front-

No producer? You just produced it.

Yeah, I always produce the records, but there's always a co-producer that does it with me. And the co-producer always engineers and stuff like that too.

Yeah.

And I'm not even saying that any of those experiences were bad because each of those experiences were wonderful too, but we just kind of realized this time, it's like the energy in the room changes. When one different person's in there, everything changes. Even if a FedEx guy comes to deliver a package or whatever, the energy changes. So we found that just the five of us, we could be more vulnerable, we could be more sensitive. We weren't as afraid to make mistakes, to go for things because there was nobody else in there. So that was a really, really beautiful thing for us, this record. I mean, in some ways it was harder because I'm simultaneously trying to get a great guitar take and a great vocal take and go chase down the snare drums blowing up too loud or whatever it is. But in the end, it was really cool. I think it was worth it.

And is the songwriting process, is it a collaborative thing with MMJ or is it something that you are bringing in a bunch of ideas and then fleshing it out with the band? How does that work?

Well, yeah, I write all the songs, but it's interesting. I like to leave room for God, leave room for the spirit to come in.

Yes.

I try not to tell the guys too much anymore other than just like, "Oh yeah, this song's G, A and D or whatever. And here's a simple way of how it goes." Lots of times we like to get into a circular state where we'll just play round and round and round and round and there's no beginning or end. We'll go off into an improv moment or whatever and we'll find our way back to the verse or the chorus. And somehow within that, I like to think of Miles Davis records or whatever, where they would play and play and play, and the album you hear is the edit of their favorite takes or whatever. So that mentality really works well for us because a lot of times, if you're going, "1, 2, 3, 4, let's get an amazing take," oftentimes you don't get an amazing take. We just kind of get into that circular way of doing it. And I've found that to be really, really helpful.

I met this guy, and I'm so embarrassed that I forgot his name, but he's a legendary producer from 70s and 80s. Have you ever been to Shangri-La before? I imagine you have.

Yes. I did this thing called Monsters Of Folk a few years ago. We recorded some of that at Shangri-La.

Yeah. So sometimes Neil Young will be coming in and out and they'll just be someone sitting at the table having lunch and you just sit down, you're like... I just remember shit, even though I'm embarrassed I can't remember his name right now, from like liner notes and being such a fan of who engineered what my whole life. And I was like, "Oh shit, you did the Eric Burdon and War" And he was like, "Yeah." He told me this story that on his second day, literally working at like United Artist Studios or one of those studios, he was the engineer. And they were either doing "Spill the Wine" or "Me and Baby Brother," like some classic record. And that's what they did. They would just play for 20 minutes." And they just looked at him like the new kid and was like, "Alright, just take the best three minutes and cut it down and print it to tape. Okay?" So this dude, obviously, I'm sure any three minutes you would've taken of those guys jamming would've been pretty great, but I also love the fact that he's changed the course of history by just what he decided to do.

Oh, yeah.

So, is that similar then to your process?

Oh, definitely. I mean, it is crazy to me to give somebody outside that choice, unless you're consciously, obviously working with a producer that you trust and love or whatever. But for me as the producer, I can't imagine anybody else picking those three minutes. You know what I mean? Because I really get into to the... I mean, I'm sure you know this feeling too. It's like, especially with drums and stuff like that, it's like you're dealing with milliseconds of what makes a beat swing or what makes a beat do this or that. You're dealing with all these little bitty fractions of things. And when you feel the moment, you feel it. You know what I mean? And you know that's it. And the moment 10 minutes before could have been fine too, but it wasn't as glued or whatever it was about that moment that was the moment. That stuff is fascinating to me.

A remote, beautiful, imaginary place where life approaches perfection. That's the dictionary definition of the term Shangri-La. The real Shangri-La is actually not much different, situated in Malibu on an idyllic piece of land just above the Pacific Ocean, now owned by Rick Rubin and the preferred creative Eden of everyone from Frank Ocean to Kanye, to Adele. It was first converted into a recording studio by Bob Dylan and The Band in the early seventies. And that's what it feels like, really. Like someone went into a lovely rustic beach house and put a live room and a control room right in the middle of it.

Like many other revered studios, it has a very specific energy as soon as you step foot on it, religious really, like you're on hallow ground. Part of it is the ridiculous setting, the contrast of this gorgeous green lawn and the sound of the ocean only a minute down the hill. And part of it is that weird Juju that you just can't really put into words. Like stepping into a historic old church or temple. And then there's the knowledge that all these heroes and greats were there before you, and that somehow that spirit, that energy, that creation is still in the walls. And it gives you this extra reverence for everything you're working on. It really makes you want to raise your game, so to speak.

We were lucky enough to get in there when Rick was out of town, the first time being for Lady Gaga's album, Joanne. And it's also where we happened to write the song "Shallow." There really is something about it. Maybe the fact that it feels so cut off from the world. You go in there and you feel inspired to create in this unfiltered fashion.

And the other thing is there's a couple of little studios on the property. So the fact that you might be working and glimpse Neil Young passing by the window only adds to the surreal layer of legendary-ness. I remember when Gaga brought him eggs from her chickens on one occasion. It was very cute.

The thing with these special studios is it doesn't mean you're guaranteed to make something brilliant the minute you step foot in there. But you are aware of this extra presence. You are maybe more likely to tap into something below the surface noise and the chatter that clouds us. That Juju, which is the writing and recording process.

Talking of producers and co-producers, I mean, you have worked with some really legendary dudes. And the first one that just jumped out, that I wanted to talk to you about, because he's done so many things that I just think are incredible, is John Leckie. And obviously that was early on in MMJ. But John Leckie who did the first Stone Roses album, which would put you in the books for any English person ever, and then Radiohead, The Bends. I mean, it's like if you just did one of those, you would be sort of in some kind of rock-and-roll hall of fame. How did you get to work with him?

John, man, he was just so nice. We met him, he came to see us play somewhere in London. We played the Astoria or something, you know?

Yeah. Did he do Z?

Yeah, he did Z with us. Yeah.

Okay.

And it was funny because we just met him and he was really, really kind, really kind of quiet guy. You know? So it was interesting because that was one of the first times we'd ever worked with somebody who wasn't a friend. We had a lot of fun, and I mean, he has ears of gold. And he's just like one of those people that, for whatever reason, where he puts the microphone and the millimeter he chooses, yeah, and just whatever he chooses to do to it, those kind of things, people like him, engineers like that, the truly great engineer... Because whatever, I can mic a guitar cabinet or mic a drum kit or whatever, and do a good job of it or whatever. But those engineers that have those golden ears like him, it's really mind blowing.

Were you a fan of those records, like as a band? I was thinking in my head like, "Wow, is this a band from Kentucky?" Like were you a big Stone Roses fan coming up? Or it wasn't so much about what he did, you just liked him? Or which...

It was a little bit of both. I thought it was really cool that he was a tape op on some George Harrison stuff and some John Lennon stuff.

Of course. I forgot about that.

And he did some stuff on Pink Floyd Metal, which I really love, and The Bends. I didn't know, I still really don't know the Stone Roses record. So yeah, it was mostly those records, mostly Pink Floyd Metal, and just his history. And then just meeting him and just sensing like this is a magical person. You know what I mean?

And it was interesting because we spoke such different languages, you know? He's such a different person than the five of us. We're kind of these five dudes that's just kind of laughing and stuff. And that was an interesting time too, because we had two band members leave and had two new band members at that point. So there was a lot of new energy going around. So I felt like we had this opportunity, and he wanted to do the record, and the timing worked out. And I was like, "Let's try this weird combination." You know?

And then Z is pretty much considered the big breakthrough record. You'd already been building shit, and I understand you had this huge following live. But I think that Z was around when the FADER cover came out. Was that around 2005, 2006?

I think so, yeah.

And it's funny because talking to a lot of people for this series are all people who have been on the cover of the FADER. And kind of what makes the nature of somebody who would be on the cover of FADER is probably that they're pretty amazing and progressive and don't really spend a lot of time looking back at their career. So it's kind of interesting to talk to people who are pretty forward thinking and making them go back and think about what was going on in 2006. But when that record really broke and you were having these things like magazine covers all of a sudden, and it goes from being like suddenly not just critically acclaimed, but commercial, like headlining festivals, this international success, do you remember what that felt like or the moment that it clicked in that something different had happened?

You know, it's funny. For us, it's like it's always been this gradual staircase of success. It's like we climb this little staircase and it's like we're just playing and doing what we're doing. And it's funny because it's like things gradually have gone up and up, and up, and up, and up, or whatever, but never by any insane number-one hit single standard. You know? Because I've talked to a lot of bands and read about a lot of bands who have had that number-one single or whatever, even if they only had one, and how that changes the scope of everything for the better or the worse. You know? So it's been interesting with us because we've had varying degrees, but we've never had that kind of mainstream breakthrough moment. It's just kind of been this thing where it's like we just play our shows and, for whatever reason, it's like it just kind of rolls along on its own.

And it's not even that we haven't wanted to have a smash single or a No.1 single or whatever. It's like the record labels that we've been with all throughout our time have tried to push our singles and tried to get us on TV and do the whole thing. But it's like, for whatever reason, that's never happened. But in some ways I think it's a good thing because it's like we've also been able to just continue on and make the music we want to make without question or without interference from the label or anybody. We're just allowed to make what we want to make, and so that's kind of what I do. And I start each record as just like, "Let's just make the record that's speaking to us right now." And of course, it would be awesome if it's successful. It's not like we don't want it to be successful or anything. But...

Right. Well, I mean, and all the records have been very successful as far as how many people you reach. I mean, I'm sure a song of yours, "Not Come Loose" or something like that, has by now reached so many more people than some song that happened to be No.1 in 2005 that we've never heard from again. I guess there's just different barometers with that.

Right, right. Yeah, I mean, just the fact that we can play concerts and people want to come see us, it's like every time I walk out on the stage and there's people out there, I'm just like, "Wow, this is still happening." Because for whatever reason, it's like the music comes to me and, of course, I shape it by the things that happened to me in my life. But at the same time, I don't. I just work with what the universe is speaking to me at the moment. Each album we make is just like what the universe spoke at that moment filtered through us. But so it's like there's never been an intention to hit a moment or climb on this trend that's like doing this upward thing, that's going to get us this hit or whatever. So I feel like in a way it's been just this really interesting journey of just continuing on and continuing on and continuing on, and watching it go up and watching it go down. And so much of it, I just feel, is out of my control.

Speaking of longevity, I went on a Steve Miller deep dive because of your cover that... Recently you covered a song of his, "Seasons," right?

Yeah.

What was that for? What was the idea of that?

For Secretly Canadian's 25th anniversary, Chris, one of the people who started the label... We kind of started out at the same time, and there was a moment back in like '98 or '99 or whatever that we almost signed to Secretly Canadian or whatever. So we've been casual friends. And he just reached out to me and said he wanted to hear me sing that song. And I'd never heard that.

Oh, he picked that. You never heard it?

No, I'd never heard it before. And I was like, "Okay." I was like, "I'll listen to it and check it out." And I loved the song, and so yeah, so I covered it for Chris.

Yeah, it's beautiful. But I went and listened to the rest of that album of his, Brave New World, which is like... It's pretty fucking amazing. It's like good psych rock where the drums sound like all the kind of Nuggets and they're very thin and break beating. And there's about three songs that just open with two bars or four bars of like a drum break beat that you would just be like, "Oh my God, I can't believe no one's sampled this." But then, yeah, I don't know, it's just funny. He has this really cool San Francisco sound, and then obviously three years later, he's making "The Joker" and "Rocking Me" and all this kind of shit. And I have a lot of respect for those people that just evolve through eras and as sound is changing, but yet the thing that you do is kind of magic.

And then when I first heard about you, and I was probably deep in my sort of Dap-King hip-hop world in the mid-2000s, and what I noticed that everyone kept saying is like, "Oh no, but you should check out My Morning Jacket. Or you should check out Jim James, because he's got this crazy soulful voice." That's what everybody would say. And obviously, I mean, you know what you sound like, and you know that people love your voice for that thing. But what were your influences and your roots coming up singing? And how did you find that range? Was it like, did you listen to a lot of soul music growing up? I'm just super curious.

Yeah. I mean, I just love music so much. It's kind of endless. And I love going into different voices, playing different characters for different songs. Like sometimes I love going falsetto. Sometimes I love yelling really loud or whatever. Or sometimes I love doing really deep stuff or whatever. Yeah, I mean, there's so many people like Curtis Mayfield and Dylan, and Aretha Franklin, and Marvin Gaye, and I mean, so many people. A lot of my favorite stuff too, I don't even know the singer's name. Like a lot of my favorite music is like lost, Numero Group, or Light in the Attic type stuff. You know, gospel stuff that's been lost and rediscovered. I've really enjoyed that whole phenomenon over the past decade or two of these labels finding these lost releases. And those things bring me so much joy. So I think a lot of people who have shaped my vocal style, I don't even know who they are.

Yeah. I know you talk about the Donnie and Joe Emerson.

Yeah, that's such a great... Donnie and Joe Emerson, yeah.

That's just... You could spend your entire life just listening to like unearthed music and gems from back then without... And you could like never have to listen to new shit. But yeah, I've seen you talk about that Light in the Attic stuff a lot, and that stuff is kind of amazing. But what was the music of your youth growing up? You grew up in Kentucky, right?

Yeah, I mean, really the first thing for me was the Muppet Show, because that was the first thing where I realized you could even make music. You know what I mean? I was like, "What is this thing that this frog is doing, sitting on this log?" You know? And I remember seeing Kermit sing "The Rainbow Connection" as a child and just crying. I was three or whatever, and I didn't even understand what he was... I was like, "He's making this sound with his mouth and he's playing this thing, and it's making me cry." I didn't have the words for it as a three-year-old, but I remember that with "When You Wish Upon a Star," hearing that in Pinocchio as a child too, like hearing Ukulele Ike, Cliff Edwards, the guy that sang that song, that was the voice of Jiminy Cricket. Later as I studied that song.... Have you listened to that recording, "When You Wish Upon a Star?"

I haven't, no.

Dude.

I mean, I feel like I can sort of conjure it in my brain, but no. I think I need to listen.

Oh my God. When we get off this call, keep your headphones on and play the classic, "When You Wish Upon a Star." Because everybody knows the melody. Everybody knows the song. But the recording is like the pyramids of Egypt or whatever. It is one of the greatest things humankind has ever constructed, this recording. The vocal, the choirs, the orchestra, the whole thing of it, not to mention just the recording itself. I mean, it is fucking nuts. I feel like I've been chasing that recording my entire life, not even knowing it, but trying... Because in my ultimate fantasy, I would love to build something like that.

But yeah, I mean, as a kid... And then from seeing the electric mayhem on the Muppet Show and realizing, "What are they doing? Are all the people playing music together? That's a band? That's called a band?" And then being a kid, and when I was like in seventh or eighth grade, REM was hitting really big. Out of Time was hitting really big. And then, of course, the whole grunge thing was so cool, and Nirvana, and Pearl Jam, and all those bands hitting really big. And I think that's what finally made me realize that I could try to be in a band too. Because I was like, "I'm not a Muppet." And then hair metal was really huge, and I was like, "I'm not really a hair metal dude." But then seeing like REM and Nirvana and stuff, I was like, "Whoa, wait a minute. You can just be in your band in a t-shirt. Or you could just be a person that picks up a guitar." And that moment was really, really beautiful.

And it helps that you can shred because then you can... You know, to be tasteful and then to shred when you need to is good.

I think the Muppets was one of my first musical awakenings too, I mean, because I'm a couple years older. But that was just such a thing that I had to watch every week and was so wonderful. But the songs that you mentioned, "Rainbow Connection," there's a heavy melancholy in that. Like it's beautiful, but to be so moved by that as a kid also, you must have been kind of in touch with something emotionally and something going on out there, because that's a heavy song, as a kid, to be like, "That's the one." You know? It's sad.

Yeah, it's weird that I've always been hit by that sadness, because "When You Wish Upon a Star" is the same thing. It is a deep, deep, heavy sadness. And especially when you learn the backstory behind the guy that sung it and his tragic life.

Oh. What is it?

He was this kind of novelty singer, Cliff Edwards, he was called Ukulele Ike. He was kind of like a comedy singer. They discovered him, Disney discovered him or whatever, and he became the voice of Jiminy Cricket and Pinocchio, and sang, I mean, he sang all the songs in that film, but "When You Wish Upon Star" became this insane, beyond even hit, you can't even call it a hit, it's like part of our DNA. It's just kind of a classic, tragic Hollywood story of his addictions and his demons and not being valued by the industry or whatever. He just kind of fell by the wayside. Man, it's weird too because I remember watching The Muppet Show and they did a skit based on the Jim Croce "Time In A Bottle" song, you know?

Yeah.

There's this scientist in a lab watching all these beakers boiling over and they were full of time and stuff and he was lip syncing, the Muppet was lip syncing to "Time In A Bottle" and I remember seeing that as a kid and being like, geez, what is this feeling? What is this feeling that I'm feeling as this song plays. That feeling has always spoken to me.

We've all connected with music and rhythm way before we can remember, you only have to watch a baby play excitedly with a rattle to get that. Even as early as six months, babies understand the difference between major and minor keys, minor being the key associated with sadness, sort of. Babies expressions and moods change when hearing both. What's really interesting is how James was so taken in transfixed by genuinely melancholy music as a kid, aware that he was being moved by some sentiment, something in the universe he couldn't put his finger on.

One of my favorite singers, Yebba, told me once that when she was two or three, her parents would be playing Aretha Franklin in the car and they would look back at her and she would just have tears streaming down her face, not especially sad, just so overtaken with the music and connecting to something in it, some emotion, pain, melancholy, wistfulness, or maybe just the beauty of it. I do feel like if I saw a kid crying to Aretha Franklin or in James's case, "When You Wish Upon A Star," you would have to look at that kid and be like, they are certainly tapped something maybe a little more than the rest of us.

There's something so alluring and interesting and attractive like when you have the falsetto male vocal in rock and roll, like I think of, like you, I think of Josh Homme because it's A, it's kind of spooky. It is something ghostly about the falsetto. It's almost like playing with, I mean the classic, like Skip James, like blues singers who had the falsetto, you'd be like, is he playing with like devil work or voodoo or something? But there's just that thing of like a big commanding male presence. Then, this bewitching, wonderful thing comes out. I think part of it is just like the fact that technically it's beautiful and it's impressive. It's like, if other people could sing like that, they probably would too. There's something about it. I always find myself drawn to that. Do you have any theories on the falsetto, the ghostliness, the fact that it feels like a little spooky or some shit, or for you, it's just like the way you sing?

You know, I had this realization after I had back surgery years ago and I could no longer run around as much as I used to. I couldn't jump off the drum riser anymore. I couldn't like, I used to like run all over the stage, real crazy, jumping and all this shit. I got injured a couple times, a couple different ways. I had to just stand there and sing more, just stand and play. Not that I don't move around some, but it's like I had this realization, it's like I can be even more powerful musically just fucking standing here. All this running around and all this jumping and shit is me working too hard, doing too much. I think something about the falsetto is similar in that energy. You're letting this voice come out of you in this really easy way, where it's like you're not belting. You're not forcing. You're not doing anything.

I'll never forget hearing Curtis Mayfield for the first time, the power of Curtis Mayfield and the power of his music, and the power of those records in just the way his voice is so effortless. It just flows out in this effortless, wonderful way. That was what really like turned me on the falsetto in a major way.

Was that something you knew since your teens or was that something you sort of came across?

I mean, Curtis Mayfield crept in somewhere in my 20s. No, I didn't know him that well growing up, but yeah, Curtis Mayfield and Prince, I feel like they, for me, were the ones that inspired that so much.

I mean, the things I've read about you, just when you start talking about your influences and stuff, there's always a lot of shared things. I mean, obviously everybody loves Curtis Mayfield. That's not so unusual. Gil Scott-Heron is someone that I heard you talk a lot about.

Yeah.

Right?

I mean, and Gil Scott-Heron is so interesting because his voice is so different than Curtis'. Right? That's one of the things I love most about music and falling in love with music is like then you realize shit, like I don't have to be bound to any rules. There are no rules. Not that everything you do is always going to work or whatever, but why not try?

Yeah.

Getting into like Gil Scott-Heron and we've gotten to play several times with Brian Jackson who made all those records with Gil Scott-Heron. You know?

I saw. He came up and you guys did "The Bottle." Right?

Yeah.

At The Garden?

Yeah. Just getting to talk to Brian and like feel his energy and just like the magic of those records. I mean, it's just like, if you're a person that's blessed enough in this lifetime to be given the gift of music, what a gift. What a limitless gift. It's like you can search and explore and be inspired and try different things. It's like, listening to Gil Scott-Heron was like, I'm going to try singing in some lower tones or whatever. You know?

Yeah.

Or listening to fucking Nirvana or whatever as a kid, like I'm going to scream my face off or whatever. Just these realizations that you have. Or listening to Kermit, and like, I want to, gosh, I want to do a tender ballad. You know? Hopefully you take those inspirations and make them your own. Hopefully it's an inspiration, not an imitation, but it's so cool that we're all constantly filtering each other. It's wild.

Absolutely. I don't think that you could possibly take Kermit the Frog, Kurt Cobain, and Gil Scott-Heron and not somehow make that your own. That is, like I always think of music as like play-doh and there's the different colors. You give anybody the same play-doh or watercolors or whatever, and no one is going to come up with the exact same hue when you combine those things. It's just a thing. Gil Scott-Heron, and I don't know what kind of music, I think I was familiar with like some 70s funk and R&B. I liked The Meters, I liked The Ohio Players, but when I heard Gil Scott-Heron, I was probably 15. I think I accidentally turned on some cool college radio station in New York, like FUV and I heard, and I'd never heard, when it was like, "You may not tune in and cop out." Like the whole, my brain. I was like, I do remember it was one of those real moments. There's probably 5 or 10 where I stopped in the tracks. Just like "What is going on right now?"

Yep.

It was just so fucking arresting.

Oh my god. Yeah. In those records like "Pieces Of A Man" and "Winter In America," those Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson records, I feel like, are some of the greatest records of all time.

Yeah.

They're just unbelievable.

A good friend of mine, this guy Richard Russell, who started XL Recordings, XL Recordings was a label out England that started with The Prodigy, but then signed The White Stripes and MIA and a lot of cool shit. He produced that last Gil Scott-Heron record, I'm New Here.

Yep.

His retelling of stories of what Gil would say, it just sounded like the most wise sage, but cutting to the point, never sugarcoating shit.

Yep.

You would just want him in your life as some kind of spiritual guru.

Yep.

One thing as well, if you don't mind talking about, is transcendental meditation. I mean, I discovered it and it's had a very positive effect on my life. You've talked about you've done records and stuff for it. Can you tell me little bit about how you found it?

Yeah. I mean, my journey with meditation has gone lots of different ways. The first thing that I found that appealed to me was insight meditation, like Jack Kornfield. I don't know if you've heard of him.

Yeah. I have heard of him.

Some of his books on tape or whatever of listening to him talk about meditation as if you're in his class, and he kind of was one of the first people that opened the door to me of meditation being this very normal thing, this very useful. Because I think a lot of people, I mean, myself included, I thought if you meditated you had to be reach some enlightened state. You know?

Yeah.

Floating off the couch and seeing these green lights or whatever. I kind of, listening to Jack Kornfield, I kind of realized that meditation is just about like seeing really what's going on in your mind, trying to become one with the universe. That was kind of breath based meditation. Then I discovered transcendental meditation, which is focused on the mantra as opposed to the breath.

Yeah.

That really made sense to me, because the breath, I don't know if it's like being a singer or whatever, but I would get too hyper focused in not a good way on my breath and just kind of not feel comfortable. The mantra became really, really helpful for me. One of the most beautiful things I heard when I was learning that was that like the goal of when you're meditating, when you're sitting there, you're thinking about all your problems or you're thinking about the grocery store or your mind's busy and then you try to say the mantras in your mind as faintly as possible. It's like it's disappearing and the space between where the mantra ended and before you start thinking about going to the grocery store again or whatever is where you've transcended and where you've reached the same level of consciousness as a leaf or a deer or a droplet of water or a stone or whatever.

That just blew my mind and really tuned me into nature too, of just trying to find that nature consciousness, of just being alive and aware like a tree would be. Therefore, trying to be more able to just enjoy this moment and not be thinking about all the moments from the past and the future and all these things, just trying to be in that consciousness. I always encourage people to just follow their heart when it comes to meditation and try as many different kinds as you can.

I do like the transcendental meditation, although it's hard for me as someone who's, like a lot of people, very self-critical or whatever to ever absorb fully the notion that there's no wrong way to do it. Because of course, there's a way when you've been told that you're going to silence your mind and you're going to find this great place, and all you can think is of the grocery store and the thing you have to do to be like, I'm doing it wrong. Like why can't I fucking do it? But when you do let go of that and not try to control it, it is a wonderful thing. It is just a great exercise in probably not trying to control everything period.

Well, yeah, I think that's the most important thing for people to realize when they hear that chatter, what's going on in your mind. For us to sit on a cushion and not have our phone open and not have our computer open and sit with ourselves and see what's really going on, like in this way that we're always trying to distract ourselves. We're always trying to work on something or talk to somebody or look at social media or whatever. It's like, if you can get away from all that shit and see what's really going on in your head and yeah, hopefully you can have these moments where you transcend or where you forget about the grocery store or whatever, but it's like even if you don't, you're still doing this really beautiful work of getting in touch with yourself in this deep way.

Yes.

Another thing I tell people that they told me when I first tried to start learning meditation is you got to think of it, it's called a practice because it's something that you practice like playing the piano. You don't sit down at the piano and instantly play like a genius. You know? You got to work. You got to practice. I try to remind myself of that too because I'm in the same way. I mean, I go through terrible spells where I'm like, I can't meditate and I don't meditate for weeks or whatever. I'm so down on it and so down on myself and then I like, okay, all right, all right. You got to remember, it's just a practice.

Yeah.

You're going to be practicing forever. You're not supposed to get anywhere. You're not supposed to win some contest with this. Yeah. It's wild.

I guess it's just the idea of like, you're actually not your thoughts. Those thoughts that are zipping around in your head are really just sort of electromagnetic impulses. The minute that you realize like actually you're the person sort of behind that almost. I always sort pictured it as there's a little lighthouse in the very back of my brain and that's a thing that's kind of shining a light. All the other stuff is just these sort of whatever you want to call it, bats in the Belfry sort of flying around. Just remember that you're just this kind of pure light or something.

Absolutely. Yeah. That's like the essence of your soul. Yeah. Your soul is not your thoughts.

Our thoughts are really just electromagnetic impulses darting around the brain, or at least that's what my therapist tells me. Of course, we live so much within our brain and our thoughts, it's impossible sometimes not to let those impulses basically define us. For example, if I'm having a bad day, I might have the thought I don't want to go to the studio today because I'll have no good ideas, and if I go, everything's going to suck. That thought feels very real to me at the time that I think it, almost as if it were a fact. The fact is actually that this thought is not grounded in any reality whatsoever. It's not based on any real prior history and it's pretty much all supposition and some doomsday fortune telling.

Of course, in that moment it feels like the truth. It's hard for me to extricate myself in that becoming my identity at that moment. On a good day when I get to the studio, yes, I might second guess and cloud my own creativity for the first little while. If I hit on something I like and start working on it, before I even know it, three hours has flown and that really is its own form of meditation in a way. It's the purest part of creation, when the chatter and the clutter fall away and you're tapping into something which even you don't quite know where it's coming from.

There's this Rumi poem where he's talking about, my friend just sent it to me last night, it's so beautiful and it's talking about the soul in that way, where it's like ... I'm trying to find it and I'll read it to you. Yeah. It says "One who has lived many years in a city, so soon as goes to sleep beholds another city full of good and evil and his own city vanishes from his mind. He does not say to himself, this is a new city, I'm a stranger here. Nay, he thinks he has always lived in this city and was born and bred in it. What wonder then if the soul does not remember her ancient abode and birthplace, since she has wrapped in the slumber of this world, like a star covered by clouds, especially as she has tried in so many cities and the dust that darkens her vision is not yet swept away."

I thought that was just like a beautiful way of thinking about that way, it's like our soul is this eternal golden light that we can't understand. You know? It's like at night in dreams, we go off somewhere else. You know? But the soul remains. Same thing with like, yeah, our thoughts or meditating or the things we go through. It's like our soul is still there, behind it all, the observer. Yeah.

I couldn't tell because I saw the video, the new video first before I heard the song. Is it a little bit of a statement on our current fixation with just, I guess whatever smartphone culture is, whether it's social media, whether it's instant gratification, whether it's having to buy things online. I mean, everybody's been indoors for the past year and a half, so there's obviously a ton of that going on.

Oh, definitely. Yeah. I mean, I feel like these things, these computers and these phones and these social media platforms and all this stuff, they're wonderful tools. They're really, really beautiful tools and they could even be responsibly made and responsibly powered. They could be powered by the sun and the wind, but it's like, they've turned into these terrible addictions that they're destroying us as people. They're ripping us apart. They're ripping the planet apart and it's like we're just all buying it. We're just all going right down the pipeline with it.

One thing I've found that does help is just going out into nature, going out into nature and meditating, trying to just put your phone down and just go outside. Even if you can't go to some crazy mountaintop or some insane forest or something, just literally close your phone and go outside, and just be in the moment.

Yeah. It's killing us. It's ripping us apart. It's made this ... People can't even talk to each other anymore. It's like there's no forgiveness. There's no notion of agreeing to disagree. I feel like there's so many people ... There's this ridiculous notion of right and left or liberal and conservative that's just ... It's not true. It's this divide and conquer techniques that are used so well to keep people down are working on us. It's just classic shit. If we could wake up and see that we're all more alike than different, and just agree to disagree on some things, I think that would be a lot better.

I think if social media, and phones, and everything disappeared tomorrow, and we all were forced to just deal and interact with the people around us, I think the world would be a better place overnight. Because you treat somebody better when you have to look them in the eye and listen to them.

Of course.

Than when you're on Twitter, yelling at them about something they're not going to listen to you about anyway.

That's the easiest thing ever, to argue with someone that you know you're never going to have to see. I'm saying the most obvious thing.

I actually remember going down to Kentucky for the first time. I haven't been so many times. I was going down to Louisville to work with the Nappy Roots, back in like 2002. Do you remember that group?

Yeah.

I remember I was waiting for the big culture shock or something. This was even in a different time. America wasn't polarized as it is now. I just remember just being in the back of this guy's cab, and just talking to him. He seemed a little bit buttoned up and sort of conservative Southern to me, but we just talked. I was like, "If I grew up here, I would be like that." It's just this idea that, like you said, we just can't see the humanity in anybody else's experience, why they might be that way.

Yeah. Right.

Do you talk about your political leanings, or do you like to keep away from that shit?

I'm always down to talk about anything. I'm really into encouraging people to vote. I'm into encouraging people to use the existing system in order to hopefully change it for the better, because I think it's a deeply flawed system. But I try to do it in a very open way, in a very kind way, because I feel like we need more conversation between people who disagree.

I'm never trying to come down and be like, "You're a fool for thinking this. How could you do this?" because that's what's dividing us. But back when I was on social media, I would post things or whatever that was going on. Yeah. I don't know. I've always tried to say what I feel or what I believe, but also try and do it in a way that leaves the door open for discussion, you know?

Yeah. I think that's healthy. What are you doing ... Because you're touring right now, as well. Are you asking people for vaccine cards, or how ... What are you doing for the shows?

Yeah. Every show you have to have proof of vaccination or proof of a negative test. It's all complicated. It's all confusing. Every day is different. Right now we're in a crazy circle because one member of our touring party got COVID. We've had to reschedule ... show, and it's like even ... Whatever. They were fully vaccinated and fully careful. We're taking every imaginable precaution you can possibly take, but still, there's so many aspects that are out of your control.

But it seems like, to me, at least this is what we've come to, is we're all trying to move forward in this world. It's not ideal, and we also haven't figured it out yet, but we're trying to move forward because we have to. If this is the world we're going to live in, we've got to hopefully figure out some way to still go to shows and still be with each other in person. But we have to have a mask on, we have to be vaccinated. We have to do these things to show each other that we care about each other.

The whole vaccine argument, obviously, whatever, people are free to believe what they want to believe. I don't know. I just try to listen to the science and go with what seems to make the most sense, and I really try to not listen to weird things on Facebook, or cable news shows, and stuff like that, because I think that stuff is toxic and misleading. But everything's so warped right now. People are like, "You can't listen to the science. That's the government, and they're trying to fool you," or whatever. At the end of the day, you just have to follow your heart, and go with what you feel like is the most truthful thing.

I think another thing that's important is people that need to realize, when they talk about their personal freedoms in this conspiracy theory and that conspiracy theory, is a lot of it is not all about you. It's about keeping everybody safe. It's not just all about you all ... I think that's another thing our social media has done to people. Everybody just thinks about themselves. It's like, "My this, my that, my this." It's like, "It's not all about you."

I remember when, fucking, they tried to introduce motorcycle helmets as mandatory. People were like, "No fucking way." I think there is this thing of "don't tread on me" that runs since the fucking American revolution through the thread of the civil liberties and stuff that is somehow ... Me, I didn't even get my citizenship until 2008, but it's a very frustratingly oversimplified thing, but which is somehow inextricable from the American experience. That part is just nuts. Now everybody wears motorcycle helmets and no one questions it, and it's just like, "Oh, yeah, of course." You don't want to die, right? You wear the helmet.

Yeah.

Then the other thing is ... The song that you wrote, is it called "God's Love We Deliver"?

Uh-huh (affirmative).

Yeah. That's my corner, with that building.

Yeah? You live right there?

Yeah. Will you tell everybody, because it's sort of a beautiful story, what that song is and how, just, driving past that building inspired you to write the song, and then the lyrics of it?

Yeah. That's so funny, man. I haven't thought about that song since 2012, or whatever. Yeah. That was on my first solo record.

I was living in Chelsea. I lived in Chelsea for a while, and I would go down there to catch the train, or whatever. I just love walking. That's one of my favorite things to do, is walk New York. It's just endless.

It's the best.

It's the best. Yeah. I would just see those letters on that building every day, and I was like, "What a beautiful sentiment." To me, one of my things that I really love is this notion of God being a very non-polarizing word, and being a very free word and a very open word. God just being this ... Whatever God is to you, great. That's awesome. But this notion of God ...

Because to me, whatever, God is love, God is music. There's so many things. God is beyond. God is Alice Coltrane to me. God is beyond so much that we could even put into words. But this thought of delivering God's love, that being one of our main purposes in this realm while we're here, just was such a beautiful thing to me, such a beautiful thought. That I love that they put that on a building. I wish that was on every building, you know?

Yeah.

It's just like ...

Do you know what originally was the charity that it was, or anything?

I'm trying to remember. I can't remember what it was.

They started ... That when the HIV and AIDS crisis really hit New York, you suddenly had all these people that weren't really recognized as having anything by the healthcare system. They were basically left alone, like lepers. This charity came to deliver meals to all these sick people in their homes. That's what it was, and bringing it to all these people who were wasting away from AIDS and HIV in their homes.

I think David Geffen was probably the big proponent of it. He was the one who really, I think, put the huge amount of money and put the building up. He obviously did a lot for the AIDS crisis, but ... Even that is such a beautiful story. The idea of delivering God's love, like literally going around to bring meals to people, and stuff like that.

That is so beautiful. Yeah. I wish we could all find that mentality, because it's crazy how there's so much hatred and anger built into the notion of God too. There's so much religious hatred between different religions, and stuff like that. Our goal should be to find a way to love and accept each other. That's part of what makes life so wonderful.

Just from being an outsider, I always think of the most soulful versions that I love of Southern rock. It could be like the Allman Brothers, it could be Marshall Tucker. There's so many things. It's really easy to make this kind of thing, like, "That's because the church is still stronger in this part of America, so it's just genuinely more soulful or more spiritually, and that bleeds into the music." Do you ever think about that, or is that anything that holds any weight to you?

The church for me growing up was a very difficult thing, and it wasn't a good thing.

It wasn't?

It wasn't an inspiring thing. It was very strict and very ... It was terrible. I went to Catholic grade school and all-boys Catholic high school. It was nightmarish.

Okay.

Just the cruelty, and the way that ... It's all warped. I'm not saying this in any blanket judgment way of anybody's religion, but that was my personal experience. The only place that I could find God was in music, and in my friends. Those were the only places I felt the spirit, however you want to think about the spirit.

Then, really, I'll never forget hearing "What's Going On" for the first time, and hearing Marvin sing "God Is Love." I was like, "Wow. Yes. Okay. This resonates with me," and then digging for old gospel records and stuff.

There's this record store in Lexington called Pops Resale consignment when I went to college for a couple years. I loved just getting dollar gospel records or whatever, and feeling that, and feeling like ... Okay. I'm hearing this in the music.

Then, continuing on to Alice Coltrane ... Alice, listening to her, to me, that's been my most recent revelation on God, or whatever, because I just feel like there's ... When I listen to her sing, she did so many things. She's a amazing harpist, amazing pianist, whatever. I think she could do anything. Some of the synth stuff she did is mind melting. But when she sings ...

She had an ashram out somewhere near Malibu, out in LA. She would record these cassettes just for her congregation, or whatever, at the ashram. For years you've been able to get them as bootlegs, or whatever, and they sound so amazing because they're just literally cassettes somebody transferred to digital. They're all hissy and all weird, but her voice is insane. There's these crazy synths zooming in and out and stuff, and she's playing the organ. Recently they took these tapes and ... I don't know who decided or why they decided to do it, but they stripped all of everything off of it. All of the synths, all the reverb, everything.

It's just her sitting at this organ playing, and there's nothing ... It's crystal clear, and the bass notes off her organ are like the roots of God, rattling your heart open. Her voice ... The depth of humanity in her ... Her voice is like a tunnel of souls. At least for me, it's like I can see all the way back to when humanity began, and I see all the way forward through the tunnel of her voice. It's every shade and spectrum of humanity, all of the evil, all of the horror, all of the joy, all of everything is in her voice. To me, that's the presence of God. That or standing near my favorite tree, or going out to see the redwoods, or going out to see the Sequoia trees, or just ... To me, that's God.

Any involvement I've had with organized religion, or whatever, growing up, I came to realize that a lot of that stuff is just big business. They want your money. They don't give a shit about your soul. I think that's where so much hatred comes from, misplaced religious beliefs, or whatever, that are so warped, warped around this idea of just trying to get money from the parishioners, get money from the congregation. I just always question that. When somebody wants your money and God's involved, something's not right there, you know?

Yeah. I love that. You actually said basically the same exact sentiment almost to the word when we started off this thing, talking about rooms and recording studios.

There's a Quincy Jones quote when he's talking about working on some ... I don't know what he's working on. Off the Wall. We Are the World. He's like, "Yeah, it was me and Lionel," or something, "and, of course, you always have to leave a little space to let God in the room." It's that whatever God is that ... Yes, you can call it your higher power, this spiritual thing, this thing that ... Just being aware that there's ... Yeah. There's something beautiful that's ... Whatever it is, outside of all the shit that we can control.

Yeah. It's wild. I'm sure you know that feeling too. You're in the studio for 12 hours, or whatever, toiling away, and it's like nothing's happening. Then all of a sudden, the spirit shows up, and you're feeling it, and the thing's happening. Something's happening. Something's speaking beyond us, beyond anything we can understand, because you're still doing the same thing. Whatever. Drummer's still playing the same drum kit, bass player's still playing the same bass. In all practical reality, nothing has changed, but that moment when the spirit enters and everything shifts, that's it. You know that's ...

That's the magic.

Yeah.

Yeah. Listen, that's a really wonderful way to end. Thank you for giving me so much time. It was fucking great hearing you talk.

Yeah. Thanks so much. I appreciate it. Yeah. Great talking with you.

All right. Great. Okay. Take care, man.

Thanks, Mark.

As soon as our interview ended, as promised, I listened to the Cliff Edwards recording of "When You Wish Upon a Star." James is right. It really is a thing of wonder. The song itself, the arrangement, but for me, mainly Cliff Edwards' gorgeous falsetto that both pulls you in like a Pied Piper and can break your heart in a few notes.

It's also a testament to James' wonderful, very intelligent, but also childlike enthusiasm for all things musical and spiritual. The front man of one of modern rock's most enduring bands, legendary badasses live, the fact that the thing he was most excited to tell me about was this song, this Disney song, and how much it moved him ... Thank you, Jim James. Take me out with the fade.

The Prisoner Wine Company is an official sponsor of UNCOVERED. For a limited time, take 20% off & get Shipping Included on the star-studded Prisoner lineup by using code: UNCOVERED at theprisonerwinecompany.com/uncovered.

Offer valid on first time online orders only for U.S. residents of legal drinking age through 12/31/2021. Rebate requests from alcoholic beverage retailers, wholesalers, or anyone suspected of submitting fraudulent requests, will not be honored or returned. Limit 1 offer per household, name, or address. For more information, contact customerservice@theprisonerwinecompany.com. Other exclusions may apply. Please enjoy our wines responsibly.