Mark Mora

/

Press

Mark Mora

/

Press

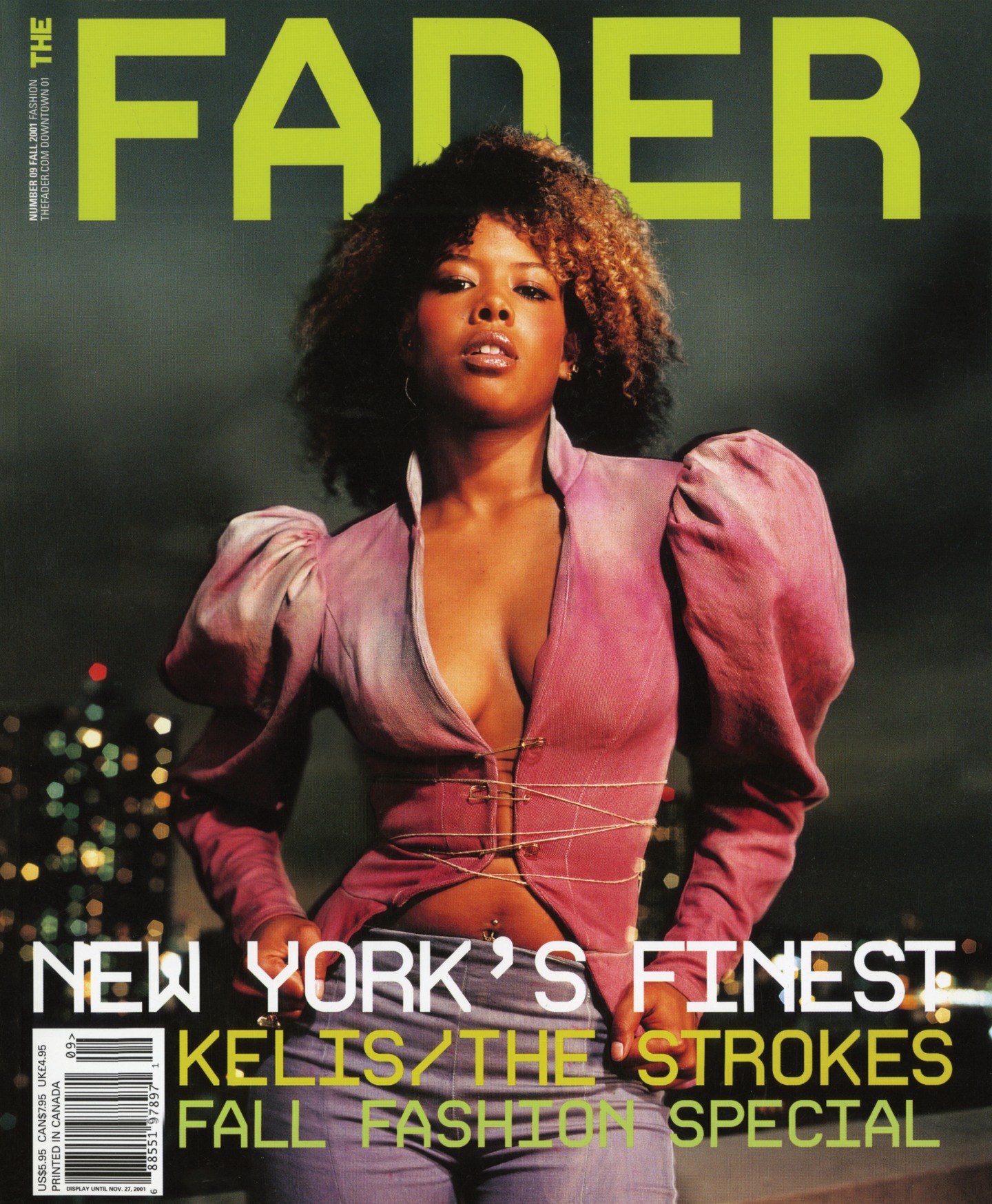

Today I'm talking with Kelis, the genre-defying pop star responsible for some of modern music's most weird and wonderful bangers. Kelis appeared on the cover of the FADER in the fall of 2001 for issue number nine. At that moment, she was about as New York and painfully hip as The Strokes were, and they happened to grace the back cover of that same issue. Her debut album Kaleidoscope had already vaulted her into the spotlight internationally. And its follow-up, Wanderland, was set to cement her status as one of the world's most exciting artists. I remember being completely stopped in my tracks when I first heard Wanderland's lead single, "Young, Fresh N' New." The vocals were so exciting and the production was the Neptunes at their finest. Hard-ass minimal drums with so much future funk, these weird aggressive robot noises and a super soulful bridge that seemed to come out of nowhere and take you to melodic R&B heaven.

The Neptunes were obviously on their way to becoming one of the greatest production duo of all time. But Kelis particularly was the collaborator through which they seem to exercise their most outer galaxy leanings. Not unlike the synergy that Missy, Timberland, and Aaliyah had created just across town. I mean it's crazy to think that all of this was going on within 10 miles of each other in Virginia Beach, some of the greatest, most future leaning pop music of all time. Anyway, "Young, Fresh N' New" comes out and Wanderlust is set to be her anointing. But instead, it turned out to be an extremely fraught time and Kelis's career. In fact, label issues were so bad that the album was buried in the United States until only two years ago, when it suddenly appeared on streaming services out of nowhere. Kelis was breaking boundaries in music, fashion, culture, incorporating elements of hip hop, punk, science fiction embodying the term Afropunk before it even had a name.

And as is often the case when you defy genres and boundaries and stereotypes, the gatekeepers, be they the labels or the radio or whoever, well they don't get it. And they usually too shook to let you through. But by sheer force, raw talent, ambition, and as she puts it, no choice but to be an artist, Kelis rebounded with the biggest hit of her career, the all timer "Milkshake" and it's excellent accompanying album Tasty. But while still delivering excellent record after record, Kelis got tired of an industry that didn't understand why this young Black woman wouldn't stay in her musical lane. So, she took time out to study at Le Cordon Bleu, the most prestigious cooking school in the world. She graduated, wrote a cookbook, and became a culinary boss with our own line and a show on the cooking channel.

I'm a genuine Kelis fan. She has a really unique voice and has made records that are actually points through which I can remember what I was doing in my life. She's also incredibly bright, has one of the best laughs, and now lives on a farm in California. What does a true icon, an arbiter of fashion, art and culture, whose as New York as graffiti on the subway do on a farm all day? Well, let's find out.

Mark Ronson: Are you on the farm? Because I've obviously been doing my deep dive Kelis research and I didn't realize that you'd sort of have this big farm...

Kelis: Yeah, we're really South California, towards San Diego.

Okay. And can we talk about it? Because I am sort of like you've had so many lives and you're such a New Yorker to me, but then you also lived in LA and you're like, I just couldn't live in LA and talk about hikes and juice cleanses anymore. And if I'm going to live in California, I want the thing that you live there for, which I guess is this farm.

Yeah, I wanted space. Yeah, I wanted to see like trees and stuff. To me I am such a New Yorker, like to the core. I'm such a New Yorker. I think when you're born in New York, you kind of like come out the womb, like you will hate California. You will hate LA. And like I was bred to hate LA. And so, when I finally came out to LA I was like, I hate it. And then you get used to the lifestyle and then you're like, okay, I'm not out as late as I used to be. And because in New York it could be a Tuesday and you still might get home at like 4:30 AM and you're like, damn it.

Like, this is terrible, But in LA that doesn't happen. So, I think once I got over the idea that this is nothing like New York, even though people try to trick you and make you think that it's a city, it is not, it is a giant suburb. I am not a suburban type person. I am an extremist. So, either I want to be in the best city in the world or I want to be the total opposite. I want to be sitting on bales of hay and walking with no shoes on and kind of like taking deep breaths and liking what I'm feeling.

Yeah, and did it have anything to do with becoming a chef and being known for food and all these things? Like was it something about growing your own vegetables in this organic thing? Or is that just this myth that I've erected in my mind?

No. No. It was all kind of part of that. It's this weird combination of my life, like I went to Manhattan Country School in Manhattan. It's like they had a farm in upstate New York and I used to have to go to the farm, it was part of our curriculum and part of our requirements to graduate. And I went there from the time I was four years old till I was in eighth grade. I love the time on the farm. It was just one of those things that my parents sent me there, I went there, it was great, I loved it. Then I went to LaGuardia, I went to school, I never thought I'm going to get it. It wasn't until I got on the farm and I was like, 'oh my God.' From day one, it's all been sort of lined up for me in this really weird way that all these things sort of make sense.

So yes, being a chef is definitely part of it. I think it was also just my upbringing. I think it was having kids and the other thing is also, I feel like I've been on tour for the past 20 years. And so, I love New York. It's funny because in all the years that I obviously grew up there and lived there, I never really, like, wrote or like, worked in New York. I suck it all up and then I would always go somewhere. So, whether I was working with Neptunes and I was in Virginia writing or I was in London and I was never in New York writing, which is so strange. So, I think when I came out here and then finding the farm, I was like, yo I have mental space. I needed space, like my brain needed space.

Yeah, that's interesting that you say that because I just moved back to New York and I was thinking what exactly what you said, like New York is this energy that you suck up and it's in you. But actually sometimes when you go to make the record, you actually need to get out of New York to make it for the focus. I just moved back into my old recording studio in New York. So, I'm like, well can't I get up and leave just now, I just moved back home. But I'm already feeling that okay, but I do need to sort of, there's something that happens. You're right. You store up all this creative sort of energy till it's at the Hilton. And then if you get to take it somewhere else.

We'll talk about where did you make because the FADER article just to jog your memory, it came out in 2001 the fall. So, I imagine that was just like in between Kaleidoscope and Wanderland and like in typical FADER fashion, it's you on the cover of one side, it's The Strokes on the other? Like, it couldn't be any more fucking cool and everything around what was going on with you at that time. But if we can go back for a second to Kaleidoscope, where did you make that?

I made that in Virginia Beach.

So, both records, Wanderland and Kaleidoscope?

Wanderland half of it was made there and then the other half we did it on a bus because I was on the road. So, we just put all the equipment on the bus, if you really listen, there's like weird sound. I was like, 'oh, it's fine. If we're on the bus, like whatever.' You could never really get it quiet enough. You know what I mean? So, there's lots of like random, weird sounds in part of that record just because we were kind of just like rolling, we were on the bus on tour. But the first record was in Virginia Beach, yeah.

And because I know Wanderland, you guys rented a house and you did it there, but Kaleidoscope. So, was that a culture shock when you first got down to Virginia Beach or was it just chill?

I mean we were such kids, man. It was so crazy. I went down there first, we recorded three songs. It was "Caught Out There," "No Turning Back." It's like one other song. I can't remember which one it was, but that record I mean it was such a different time, it was a different era. I think we did things different. We thought different also we were all brand new, so like there was no premise. It was kind of just like, 'wow someone gave us money to make music, this is ridiculous.' Like we'd do it anyway. So, we were just in Virginia and we used to work like early, we would get to the studio in the morning and we would work till like 2:30, 3:00 and then we were done.

So, that whole record kind of set up my whole music lifestyle, just how I came into it. It wasn't that whole partying and late at night, like we did not do that. We were up in the morning, it was a job. We went, we got up and we're like we're going to do this and we're going to be really like. And we recorded like 13 songs and we used 12 or something, literally like that was it. We just did it.

I remember reading an article around that time with Chad and Pharrell. And it was like, yeah, we work from 11 to five. There's no nonsense in trying to tear our hair out and we like to go out and have dinner, enjoy ourselves. And there I was, I still hadn't had a single, like iota success yet. And I'm there till like three every morning. I'm like, what the fuck am I, what am I doing wrong? Okay, maybe I'm not quite as genius as these guys, but at the same time I saw a quote that you even said in that FADER article, you're like, "yeah, we worked till 11 to three and it was just fun". And then you turned around and you kind of had this brilliant record at the end of it.

We had so many ideas, right? And we were all so young and we had not had any success yet. And so, there were no rules and music was different then, I think that that record was special because it came out at the end of an hour. It was the end of an era. Do you know what I mean? So, it was kind of like to me it felt like it was like a nightcap. It felt very like that's it, that's all folks. You know what I mean? Everything changed after that. We had no idea what was going to happen. We had no idea what any of this would mean. We didn't know what people would think about it. We were too young to care also, like we didn't care. We were just sort of like, oh, this is cool. Let's do this. And I'm so grateful that I was able to start that way because everything about it, from our work habits, that's the other thing, it was Virginia Beach. There's literally nothing to do at Virginia Beach. Okay, so like.

I mean it's true. I know also like now we think of the Neptunes in a certain way, but the fact is that they had maybe just had [N.O.R.E.'s] "Superthug," [Mase's] "Looking At Me," like maybe a couple just two hip-hop hits at that point.

It was like, whoa, whoa. That was it. People thought that was me, which it wasn't. But we didn't have, that was it. I had a song with Gravediggaz and a few other little things, but it was nothing, like we had nothing.

So, I imagine you as this like super cool, progressive, grew up in Harlem, super artsy coming down to Virginia Beach. Like not that they were small potatoes anything, but you must have just seemed like this whole new world sort of coming down. Or I imagine they were kind of impressed and you must've just seemed like this totally like artsy informed, city person coming down there.

It was interesting. I think the biggest thing was probably just the fashion. I was from New York. I went to an art school. Like I come from artist parents. We talked about that a lot and that was like I know I definitely influenced that a lot because they weren't thinking about it and they didn't have access to a lot of stuff. Virginia Beach, especially back in the late nineties, there was literally nothing. They would go to DC to shop, which the sentence alone is just like, you know what I mean? That's where we're going, that's a notch up from where we need to be. So, it was just they had no idea, right? So, we talked about fashion all the time and we talked about these boundaries and these things that to me, I was a sponge.

I met them when I was 15, like literally I was a child. But I went to this art school and I was surrounded by really brilliant, brilliant kids all the time. And it's such a New York staple, like LaGuardia is like hey. It really is that, like it feels like that, like you're in classes with these dope kid and everyone's so serious because it's very like we all knew that we were chosen. We were kids. It's a different thing. I don't even know if that exists anymore, it's such a different vibe. And so when I went down to VA and I'm like 'okay. All right. So, what are we going to do guys?' But it was great because they matched it musically and we were able to sort of like really create this thing. We were a tribe, I thought we were, it was a really fun. It was a fun time.

Yeah, as soon as you said LaGuardia, I was like oh yeah, I forgot that my high school bass player went to LaGuardia, but that is really not what I wanted to mention. I noticed in all the articles from this era, they always talk about art, fashion, your influence of sci-fi and Octavia Butler and these things. But you rarely talk about what music you were listening to at that time or what the influences were. And I was just curious if you were listening to stuff of that era, if you were just like a hip-hop kid because your dad was a jazz musician, you were always listening to old music.

Okay. So, yeah my parents were really strict and so, I wasn't allowed to listen to it. To this day I'll see videos and I'm like, 'Oh my God, that's what they look like.' I had no idea, we were not allowed to watch MTV or anything. The first time I saw Color Me Badd, I was like, what. I was so confused. So, when I went down there, it was so raw because my influences were like Betty Carter and Nancy Wilson and I used to hang out, my dad would play at The Blue Note and like I would fall asleep under the table. Do you know what I mean? Or Village Vanguard, so I was very like privy to that stuff. But I didn't really have a lot of current stuff happening. And then so, it was really a combination of really old jazz, some gospel and then the kind of stuff I would sneak and listen to. But I didn't know what these people looked like, but I would be like in my room and my mom be like, "is the radio on"? And I'm like, "no", but it would be like Biggie and Mary J and Method Man, it was a huge Wu Tang and just the nineties, the best music ever.

Yeah. Of course. And they wouldn't let you listen because of religious reasons or did they just thought it was obscene or they were just trying to just..?

A combo of all of it I think, just everything. They were like, you don't get to listen to that. I mean it was like, yeah, I remember I came home with a beeper and my mom was just like only doctors and drug dealers need beepers. And so, it was all of that. So, I wasn't allowed to listen to it. My mom was just like, there's no need for you to listen to any of that stuff. So, I didn't. The closest thing that I could En Vogue and Whitney Houston, those were like the one things my mom would be like okay.

So, those first stage performances and TV shows when you're performing "Caught Out There," I guess I just like anybody watching it, I was like, whoa, she must love Bad Brains and dah, dah, dah. Like there was such a rock energy, what it was, it was very future and the energy of your performance mixed with the song and what was going on felt like this melange. But you didn't necessarily grow up listening to rock and skate music and this kind of thing.

No, it wasn't until a lot later. No, it was raw. It was just like, this is what it feels like. And so, that's what it was.

So, when "Caught Out There," I remember that because I was producing this record on Virgin at the same time, Nikka Costa, and then I think it came out around the same time or you guys just came out before and there was such an excitement around the label. We weren't necessarily jealous, but it was suddenly like 'whoa, everybody's just talking about this Kelis record.' And I remember it just came out and it was mind blowing. And do you remember, was it in the UK or was it in the US like, where was the first place that you felt like, oh shit, this is like a thing?

It was probably in the UK. It's such a concentrated, small, it's this island, right? Like you think about London and I felt it here, but I think being there it was so new to us. I think the excitement of that really was exciting for me and being signed to Virgin, it was such a British company so I got so much attention out there, I think I definitely felt it there first. I think it really stuck with me when I came home. When I came home and I was in Harlem, that's when it hit me, like, wow, this is going to be fun.

Sometime back in 1999, I was working on my first production gig, Nikka Costa's debut album, Everybody Got Their Something. Nikka was on Virgin Records through this super cool imprint called Cheeba Sound, which also had D'Angelo, and that was our clique, Questlove, Pino, all of them, and we felt very cool about it, let me tell you. And then we caught wind of this other thing going on at Virgin, this artist called Kelis who, along with these young producers named Chad and Pharrell, AKA The Neptunes, were apparently making some very mind-blowing shit that was about to drop. And we heard it, and lo and behold, it was some mind-blowing shit. I mean, it sounded like the future and it made me more than a little jealous, and worried. We were no longer the only cool kids in the building.

Her first single "Caught Out There" was fire, and the follow-up, the speaker rattling "Good Stuff" was maybe even better to me. I was also starting to make it back to the UK to DJ for the first time and all of these Kelis tunes were some of the biggest songs in the club. It really was an exciting time. I even remember some of those performances on TV. I mean, YouTube "Caught Out There" on Chris Rock if you haven't seen it. And her hair was a different color every time she got on the TV. She really was doing things that no one was doing. She was a trailblazer.

Also, I am English. I'm sure a lot of English people hopefully listen to this podcast and I am very proud of my roots, but it always just amazes me because I spent most of my life growing up in the States. I say the States so I can sound more English, that when I go back, there's certain things that they refuse to pronounce the way that the artist intended. So you go there and it was always Kelis. You got that in the beginning, right?

Yeah. To this day, probably still, people will be like... I'm like, come on.

Yeah. And it's almost this defiance to be like, nope, we invented this language. You stole it from us and now we're going to... So even to now, English people still call you Kelis?

Sometimes, yes.

Yeah. That's not really a question. I just remembered being in England like, "Have you heard the Kelis, mate?" But it was so big, and then there were three bonafide DJ bangers, because I was going back to England certainly a lot to DJ around that time. So you had "Caught Out There," you had "Good Stuff," and one thing that I really remember from... Because I was DJing so much in clubs in that time and playing, and DJing in London a lot and playing a lot of those songs, I think "Caught Out There" has to rank at the top of the most misunderstood what the actual name of the song is of all time, because no one would ever come up to you and say, can you play caught out there by Kelis? They would say, can you play "I hate you so much right now"?

Exactly.

And going out on tour after that and playing these big festivals, you said that going out on those festivals felt a bit isolating because you had made this record with a bunch of friends in the studio and it was this fun thing, and now you're just being thrust onto some stage, 15,000 people in the middle of Europe and it wasn't really a vibe.

I think in my mind, we were all going to be together all the time. And no one really brought up the fact that like, "No, lady, when this is done, you go alone." We were all together all the time, do you know what I mean? So we lived together, we lived in the same house. We recorded together. We were together all the time. So when the record was done and I came back to New York and they're like, "Okay, great. Now you're going to go on tour." I was like, "Well, where is everybody else?" They're like, "No, you're going." I was like, "Wait, what?"

So then I'm out in the middle of Numberg or Nuremberg, I was in both, I'm the only Black person for miles and it's terrifying. And then you're doing these really grandiose things that, to be totally honest, I look back at my life now and I'm like, 'yo, I'm pretty proud of some of the stuff that I've done.' Not all the stuff, but some of the stuff that I've done. I can look back now and it's pretty dope to be able to say that. But at the time, it was my first time to Europe, I was 17, 18 years old, 19 years old, and they're like, you're going to perform in front of 20,000 people and you're by yourself. And they're like, oh, this is where Hitler used to have his rallies and you're the first Black person to ever be on a stage here. And you're like, oh, no pressure.

And it was my second show or... It was ridiculous. I was not ready. Do you know what I mean? It was so much so fast, it was a lot. It was a lot to wrap my mind around and I think that the blessing in all that was the fact that I went on tour right away and I stayed on tour for three years. So I was on tour for three years without stopping. I was just going, going, going, so it quickly became like, yeah, I'm by myself, but now I got into a flow and it became a thing. I started doing festivals that, again, I was always the only black person. It was always just me. And then all the other white bands. People were not considering hip-hop or R&B pop at that time.

So my agent was this great, older British guy named John Giddings, I love him to this day. He had Madonna, he had Rolling Stones, he had U2, and then he's like, "And I've got Kelis." And I was like, "What? How did this even happen?" And so he would put me on these stages that I probably didn't belong on and everyone was like, "Who the hell is that? Why is she here?" And he was like, "Well, she's going to open up for U2. And she's going on before the Red Hot Chili Peppers and so everyone make room." And I was just like, okay, well, here we go. That was it. And the only other person I saw that ever looked like me for about a good 15 years was Macy Gray. We'd always see each other in these random places in like Kristiansand, Norway, and we're like, "I see you. Hey girl." But that was it. It was always just me. So...

Did you end up playing shows opening for U2 and on their tours and stuff like that?

Yeah, I was on tour with U2? I opened up for the Elevation Tour. I did the whole thing with them. I opened up before Red Hot Chili Peppers. I went on right before Bowie, just a lot of crazy stuff, man. But yeah, nuts. Ridiculous.

And I imagine some of the times, it was incredible, and I imagine some of the times, the crowds were probably a pain in the ass.

I remember it was the Elevation Tour, we were in Rotterdam. We had four nights in Rotterdam, it's like 45,000 people. I got booed every night. I got bottles thrown at me, and I was literally a baby. The first night, I came off stage and I was so shook, I was crying and I was like, "I'm not going back out there. This is ridiculous. I'm not doing this shit. This is terrible." They were like, "No, you are contracted. You're definitely going back out." And I remember the Edge just being like, "You got this." He's like, "You're okay. This is fine. Don't worry. My daughters love you." I was like, "They do? Oh my God."

Yeah. I know this makes you feel cool by having me open for you, but this is a giant pain in the for me.

I was like, this is terrifying. These people were like, 'who the hell is that?' That taught me so much so I think just like, I've got this record called "Caught Out There," I'm known for being this bold, yelling, loud aggressor, and yet I'm being booed every night. My sound man, because you know the kind of stadiums where their sound men are in the center of the stadium. So he had to wear a hard hat because Heineken was the sponsor by the way, so people were throwing Heineken glass bottles at my poor guy. He was just like, "This is awful. This is terrible." So he had a hard hat, I was hysterical. By the third night, I remember I was just like, "You know what? Fuck all of you." So I remember I had the skirt on, and by the end of it, they're like, boo. They're like, get the out of here.

Because they opened the doors so early too so they're drunk, Heineken is sponsoring. They opened the doors at like five or six, and U2 is not going on until like nine. So then they see this Black girl come out. They're like, who the hell is that? They don't care. It's 45,000 very angry, very upset Europeans. So I just remember I hiked up my skirt and I was like, "No, fuck you," and I mooned all of them. I was just like, take that. Just black ass, just ass. And then I was trying to get my skirt back down.

If this was a movie, that would be like the magical turning point where everyone suddenly was turned down. Did it help?

Well, I'll tell you something. It gave me really tough skin. It was definitely like it made me... You've got to push through, right? You've just got to do it. And it was definitely hard and I was scared and all these things, but it made me better I think.

Yeah. It's an interesting thing when really huge bands take really interesting cutting edge artists to open for them, because really, what they're trying to do, it's a little bit like when you dress your dog up in a cool jacket. Your dog is not enjoying it. It's really just for you. It's a form of virtue signaling. So the Chili Peppers and U2, and God bless them, their heart's in the right place, by taking you, they're pushing something forward that they feel deserves a place but they really know that there's probably not a fucking chance that their crowd is really going to get it anyway, so they feel cool seeing your name next to them on the poster.

Right. It definitely says something about them, but to be honest too though, what was cool about it was they were already U2, right?

Yeah.

So number one, I don't expect them to care, but also, it was more, John Giddings was like, "She's coming on the road with you." I love the fact that they even were like, okay.

Yeah, totally. My friends, some fucking rap group, they were opening for the Chili Peppers and I think before, they got the pep talk that you probably got. "Don't worry, they're going to throw shit. These fans, they're animals. But just do your thing and even if you pick up 5% of the crowd." So they went on and I think that they came on and really killed it through the first song and were so in shock, and the lead singer is like, "Wow, this is amazing because you guys are so great, and they actually said that when we came out, you were going to throw beer." And that was just the worst thing you could ever say because just from that moment, a hail storm of beer and cans. Why did you say anything?

It's so funny. I was just trying to get through it really. Just get through it. Well, no one warned me. I wish they had told me that someone might boo you and throw shit at you because I might've been more prepared. I was shocked. I was like, "Wait, are they throwing stuff at me? Why would you do that?" First of all, it's glass. I was like, this is insane, and why is no one stopping this? But it's part of it. If you haven't been booed, then you're not really a performer, honestly.

And then on the flip side, I saw your performance of, it was probably "Caught Out There" at Glastonbury in 2000 or whatever. And then you have an entire tent of white, black, all races sort of moshing and going crazy. So the energy that your music and that your performance brought off really did, then in front of the right crowd must have been quite an amazing feeling, right?

It's electric, yeah. It was absolutely electric. You know, it's been such a crazy ride. I've been so graced with space and time and people listening, and hey man, we all know it as performers, there are those nights when you're like, literally, if I could crawl under the stage, I would. But then there are the other nights that keep you going back up there for another dose, when it's like, this is incredible. It's like there's nothing else like it. It's literally electronic.

Also the thing that you said about when you first went out on tour and thinking it was going to be this crew and this clique that you had made while making the record and then suddenly it's just you. And whenever I'm in the studio with an artist having a argument or maybe a heated exchange about a song and it gets to the point where we really just see it different ways, I often have to just think, this is a person who's actually going to go and have to tour and sing this song for the next two years, and I get to sit home and go onto the next record. So that's the point where I'm usually likely to give leeway on the thing because it's true. It's like you have this clique and everybody feels this ownership, but then you're suddenly the one that's just, okay, fuck. Like now, bye guys.

It's true. Well, because also too, live is such a different thing than being in the studio, everything about it. There are records that I hold so dear to my heart that I love that have never worked on stage. People are like, "We don't give a shit, we don't want to hear that. We don't come to see you for that." Do you know what I mean? You learn that too as you perform and as your career expands and grows, that there are certain things that this is who people see you as and yes, I'm never going to allow them to put me in any... I'm going to be what I'm going to be, but I also am very hypersensitive to the fact that I know what my shows look like, and I know why people are there. I know what they're expecting and I know what they need from me, and so in order for me to be able to give that, I know what I have to do. You know what I mean? So I think that's a really specific thing too. I could sing all night, but people, they're like, we want to hear "Caught Out There." We want to hear... It becomes that stuff where it's like this is your signature, this is your stamp.

Around the same time Kelis was getting bottled by inebriated Dutch U2 fans, I happened to produce a comedy record for Jimmy Fallon, who at that time was the young breakout boy next door heartthrob on SNL. When it came time to tour the record, I offered to help Jimmy put together a great band of musicians to go out and play these tunes, to which he replied in horror, "What? Great band? Are you kidding? I suck. I can't front a great band. No, no, no, no, it has to be a shitty band." So I said, "Great, can I join?" So I went on tour playing bass in a band backing up Jimmy. We opened for The Strokes, which was mostly great. But occasionally, we would get booked on these rock radio Christmas gigs where you play a couple of songs sandwiched in between maybe Queens of The Stone Age and Nickelback.

Well, you can imagine what happens when the cute guy from SNL comes out to sing his comedy tunes in front of 13,000 hard rock fans after Queens of The Stone Age have just killed it. It was a hail storm of pennies, mints, anything pocket sized that people could throw. And I kind of loved it cause it felt rock and roll, but I was also just the bass player, not really the front person and it really wasn't my music. You have to have balls of steel and skin thicker than a rhino to do what Kelis did night after night. I don't know if I'd have the metal for that.

When my own first record came out a year later, I opened for Justin Timberlake and I tailored my set for the teeny boppers. I'd play my records, but I also made it a little more poppy and PG. But when you're a Black woman bringing Afrofuturism to a bunch of mainly white people in Europe, there is no tailoring it down or poppifying your set.

You were going to tour Kaleidoscope because it was a 20 year anniversary, so I guess that was happening just as the pandemic started.

Literally, it started. We did the first two, three weeks of the tour, and then the whole world went to shit. The whole thing collapsed. And I was in Austria. It was crazy because it was like things were following us. Every country I would go to, the next night, they'd be like, "Everything's shut down. They're closing the borders." And we'd just gotten the bus through so I was like, thank God. So finally, we're supposed to go to Milan and then to Spain, and then we were waiting to see what was going to happen with Milan. And then I was just waiting, so we were like, okay, well let's go to Austria and we'll just hang out. So I was in Austria for a few days, just waiting to see what was going to happen, and then everything just went crazy so we just flew home. But it was smack in the middle of my 20 year anniversary.

Yeah. I don't want to be the 7,000th person to ask a musician this since the pandemic, but I'm going to do it anyway. Seeing you have, like you said, toured, been on the road for 20 years of your life straight, can you not wait to get back out and do some shows? Is there a period of adjustment? How do you feel about it?

Well, when I came home, it's like you feel like a crackhead. I was so like, I don't know what to do, plus I was pregnant so it was a whole bunch of stuff going on. It's hard to sit because what you have to do to get yourself ready to be in a different country every night and to be on stage and the energy, all that mental stuff that it takes to do that, when I came home, I was just sort of like, aah! What is it, Talladega Nights when Will Ferrell is like, "What do I do with my hands?" I felt like that. You're like, "I don't know what to do. What do I do?" You just feel so like a fish out of water, right? But then I was like, oh, okay. I was like, "Oh, okay." You kind of get into it, and you're like ... It hit me a few months ago. I'm like, "This is the first year in 20 something years that I've been home the whole year." I have never been home the whole year, ever. We tour every single year. It was nuts.

I'm like, "I've never not been ... This is crazy. I'm just home? What do people do? This is insane." But now I'm like, "I love it." It's been dope, because I've been able to be on the farm, and was able to do stuff and learn stuff, and do things that I would have never had time to do because I would have been somewhere else. It's been pretty crazy. It's been cool.

What kind of things?

Like how to make soap.

Okay. How do you make soap?

It's so crazy. It's this whole thing. It's hot, and the whole house is ... It's a lot.

It's toxic?

It can be. I do no lye, though. I've been making no-lye soap, so it's not toxic. It's all organic. I'm like, "Come on." But I grew all the stuff for it. Just learning about farming. I've got farm animals and stuff, so been doing that.

Because in the context of this FADER cover that you did, I imagine Wanderland is finished. I can't imagine that you would be doing a FADER cover if you thought for an instant at that moment that the US label was going to drop the ball and not put the album out. How did that go?

Wanderland basically came ... I finished the record, and then Virgin Records US had fired like 300 people, or something like that. Everyone that they had hired that was championing this record was gone. They had left. They were like, "Okay. Great. All those people who loved you are now gone. Here's a new group of people who really don't care at all."

The person who they gave me as an A&R, he was like, "Yeah. We think you should re-record." I was like, "That's ridiculous. I'm definitely not going to do that." People don't realize what that sounds ... I think people think that you're just some stubborn, bitchy, horrible person, but you're like, "I've put my life into this." It's been over a year. This is where my brain is at right now. Then I just handed him my record, like, "I'm done." In my brain, something happens to ... It's like having a baby. You're done. Where in my mind, and my heart, and my anything do you think that I'm going to go back and do another album? It's not even logical. It had just come out in the UK, and when they told me to re-record a different version for the States, I was just like, "Not doing that." That's why it didn't get released here.

Because I remember, like I said, we were making that Nikka Costa record around the same time, and there were all these amazing people at Virgin. They had had Spice Girls, Blur. It wasn't like they ... It was this cool English thing. They liked to party a lot, some of them, I think. That was kind of fun, too, because I was a 24-year-old kid. They would throw the craziest Grammy parties, the whole ...

Nuts. Yeah. It was so fun.

D'Angelo was there. It was a very creative place.

Very.

Then I imagine, yeah, having that suddenly just ... Also that just sounds like such a bullshit A&R person's line when they don't know what to say. "You should re-record"? What the fuck does that even mean? That's such a...

I was just like, "That's just so stupid and so disrespectful." Completely, it just doesn't make any sense. The way they approached it, too, I just felt like was so brazen. I just handed him my album. Okay? Budget's gone. Year gone. You know what I'm saying? Also the timing was ... It would have been a really good time for that record to come out for where I had just been, and what had just happened, and all of these things.

The reason I signed to Virgin really was because, like you just said, all of those artists to me were ... They were just beautiful, musical ... It was such a great spectrum. They had Lenny, and they had freaking D'Angelo, and they had, yeah, Nikka ... There was all this dope stuff coming out of there, so I was like, "This is a great place to be." This felt like where everything made sense.

For them to be like, "We want you to just do another album," I was just like, "I know what you can do." That was it. By that point, I was just like, "This is not going to work, because you guys are dumb and this doesn't make any sense." I just chucked it. I was like, "Oh, well. That is what it is."

I remember when I first heard "Young, Fresh n' New," and I don't know if it was because I was in England more at this point, but I just thought that shit was so great and exciting, and sounded like nothing else.

I love that record. To me, it's one of the most interesting records, I feel like, that I've ever done. It was sad to me that people didn't get to really feel it, because it was so important for what I thought the movement could have done, and where it could have gone, and what it should have been. We laid the groundwork with Kaleidoscope. Wanderland should have been all of that, but it just got thwarted.

From that point, though, that kept happening, record after record. The business of the music always just got in the way. I went to Arista, and then Arista ... Literally that whole collapse happened. Then I got shipped off to Jive, which was a freaking nightmare. It was just one thing after another. That was the beginning of a very long and arduous record label time for me.

For me, outside, it looks like this crazy ... Going to Arista, the next record, making Tasty, with "Milkshake" and "Trick Me" in this thing, it looks like this crazy triumph. You just came back from basically being left for dead industry-wise, and then have the absolute biggest record of your career and one of the most interesting R&B pop alt records.

The same thing happened, though. "Milkshake" came out. First of all, people don't realize, either, that "Milkshake" ... Everyone's like, "It was such a pop hit," and ... I'm like, I worked that record, man, like a freaking maniac for over a year before any ... Radio people were like, "No. Boo. Not playing it. Hate it. Not going to happen. We're never going to play that."

Literally I was relentless, and we just ... I was like, "This is the song." We pushed it for over a year, and then finally when it hit, it was number two, or something like that, for like 16 weeks. The only ... Got kicked out by "Hey Ya," which I was like, "Okay, that's deserving." Then when I went to put out "Millionaire," that's when everything collapsed.

That's why "Millionaire" ... It was actually "Trick Me." I put out "Trick Me." I had to pay for my own video because the label wouldn't do it. It was all this unrest. I drove to Canada with Little X, X now. We did the video, like ... Just, I was like, "How much is it going to cost? Tell me. What do I do?" Paid for it. The US really didn't pick it up because we didn't have anybody here, so the European branch, they took over, and then ... It's the same thing that was happening.

Then when "Millionaire" came out, which should have done so well here, we didn't have a label, really. By the time I got over to Jive, Jive was like ... I would have never signed to Jive. Jive would've never signed me. It was this weird ... Like we were all traded. Just, they put all the Black artists on Jive and all the white artists on RCA, and it was just like, "Okay. Have fun, kids." No one cared.

Jive, it was a mess. It was a disaster. But it was right in the middle of this record for me, so it looked one way, but, in reality, it was a disaster. It was a mess. It all happened right in the middle of the climb of that album.

"We don't hear a single." It's a cliche, but it's also true. It's one of the worst phrases you can ever hope to hear as an artist who's just turned in their album. You've poured your entire everything into this, and there's someone, in an office, usually, that doesn't feel your vision.

Music history is full of these stories. Sometimes even those with the most golden of ears get it wrong. Clive Davis apparently didn't hear what was so special about "Toxic." It nearly got left off of the Britney album In the Zone, and that song was her entire comeback. Quincy Jones thought Billy Jean was "too weak" to make the album. "Kiss" was actually a demo rejected by Prince's protege, Mazarati, that instead he decided to finish himself.

Let's be honest. Usually it's not people with golden ears. Usually it's just some guy, the proverbial mountain climber who plays the electric guitar. Yeah, that guy, who just doesn't get it.

Even worse, every now and then they have these giant switch ups happen at the label, where the guy that signed you, the guy that did believe in your vision, has now been fire. There's a new guy who didn't sign you, doesn't care about you, and really just wants to get rid of all the old shit so he can sign new shit.

It's a really harrowing position that Kelis's found herself in multiple times in her career. It's nuts. She has a hit song, "Caught Out There," and then label shakeup. Again, she has a global smash, "Milkshake," and what happens? Label shakeout. I had no idea, even. From my vantage point, it was like, "Oh, cool. Kelis. Huge comeback. Amazing. Good for her." But you really never know what's going on behind the scenes.

There was an interesting thing that the FADER did, something called Kelis Appreciation Week. Are you familiar with this?

I remember. I do. Yeah.

I've been doing this interview series for about six months, and I even dread repeating this joke. But, I was never even cool enough to be in the FADER when it was a magazine, but somehow I'm cool enough to interview cool people for it. But, in all my times, I've never heard of anybody having an appreciation week, which there is Kelis Appreciation Week. It didn't make sense why.

But one of the sub columns was, "Every Kelis video is iconic," and I started to watch some of them. It's crazy. You have Dave Chappelle. you have the Little X, which, even in the FADER thing, they comment is almost like the genesis of the "Hotline Bling" video, the lighting and the angles, and the X, who's very brilliant. I imagine you were very involved in all the music videos.

Yeah. I'm such a visual person. For me, it was always so important. I feel like people, because I was trying to do stuff that was different, that wasn't considered ... It wasn't R&B and it wasn't hip-hop. It was so important that people could see it, and you had to give them the vision. That was always huge for me. That was the best part. The music is what I did, but the video was like, "This is how I'm going to get people to understand where I'm coming from."

Yeah. It also makes sense that, if there's ever an appreciation week for an artist on the FADER, you do, in some ways, in very broad strokes, represent everything that the FADER wants to be. It's super futuristic. It's cool. It's all of those things. I realize much more now looking at it, because of course anybody could look at you even back then, be like, "Whoa. This is some next stuff." But more the trickle down and the influence, and with things like Afropunk, and how everything's allowed to be so genre-less now. You were the first. They're listing all these-

I had to fight. Yeah, for sure. It was a fight. It was a constant fight. I remember every freaking board meeting that I had, especially with Kaleidoscope, and Wanderland, and everything after. It was always like, "What is it?" I was like, "I don't know. Why do we keep asking that question?" It was constantly like ... They're like, "It's not Black music." It is, though, because I'm Black. To me, those are the requirements, okay?

Yeah. "I've met the bar."

It's pretty simple. I think I did it. I think that is what it is. It's interesting, because a publication like FADER, they always were super supportive. For an artist like me, because I got so much pushback, really, I felt that, do you know what I'm saying? FADER specifically was dope, because when no one else would put me on a cover, they would. I wasn't girly enough to do this kind of pretty stuff, and I wasn't hip-hop, so I couldn't do that. I wasn't Black enough and I wasn't white enough, and I wasn't any of these things enough.

There were a few publications that rode with me every time, and so I felt that. It was just like, "Okay. We've got that. That works, so I can show people what it is that I'm trying to do, and why this is important."

It's dope to be able to see now ... Yeah. Like Afropunk. They call it Black Futurism. There was no name, Black Futurism, back then. There was, "Kelis, and she's weird. Where the hell do we put her? She makes music so I guess we have to put her on the radio, but we don't really want to. But she just keep showing up, so I guess we should." It was a lot of that.

It was just funny now that people are like, "Yeah. FADER did a Kelis Appreciation" ... I'm like, "Thank you," because honestly it's been such a long ... Like I said, I had to develop tough skin, and I had to just forge forward and just do it, because it wasn't like I was getting all the praise and all the accolades. It's always after the fact. Now everyone's like, "Oh." I'm like, "Okay. Where were you?" It's nice, 20-something years later.

There is a nice quote at Camp Flog Gnaw. It says you were looking at the crowd, and you said, "I have 20 years in this, and it's crazy to stand here after standing in crowds that look nothing like this, and wondering how a girl from Harlem can do this. Now I look at a crowd of people that look like me and I blend in."

It's true.

What was that show like? Because I couldn't find any of the ... I desperately wanted to watch it, because I'm sure it must've been a good feeling.

It was a great show. You know what, though? It was funny. It was one of those moments where ... There were people walking up to me saying, "I am named after you." I was like, "How old are you?" I was like, I don't know if that's rude as hell, or if I should just be like, "Welcome, my child." I don't know. I'm like, "You're an adult and you're at a freaking festival? How old are you?" Because that happened a few times that night.

I don't know, it sort of set the tone. I'm like, "Oh, shit. These are children. These are kids." A lot of them know me because their parents listened to me. They're the kids of cool kids back then. Do you know what I'm saying? We were all kind of the outcasts. We were all the freaks. "You're the kids of the freaks. I get it. Okay. Dope."

I was performing, and it's like ... It made me feel like ... Not to any way put myself in the same category, because I wouldn't do that, but it did make me feel like when I went to go see Grace Jones, and I know Grace because my parents ... You know? I was like, "Oh, my God, you're amazing," you know what I mean? I felt like I had a Grace moment. I felt like that, because it was literally ... Everyone was like 17.

How old is your oldest now? Your son, right?

12.

12.

Yeah. He's 12.

What have you found him listening to that you're like, "Wait, how the hell do you know about that?" There must've been a couple things already that he's discovered from old shit or cool shit.

Both of my kids ... For some reason ... Because it's funny, because I don't really ... I love it and I listen to it with them, but it's not something I played for them, but they love Bob Marley. They both want to listen to Bob Marley all the time. But also I'm not as strict as my parents, because I'm not ... I wouldn't say I'm strict, but I'm very ... I'm an old head, so I listen to old stuff.

My little one, he's five, and he'll be like, "Can you play that ... What's the blind guy? Can you play that?" I'm like, "Ray Charles?" He's like, "Yes. Can you play Ray Charles?" I'm like, "Okay." They know that kind of stuff. I feel like, it was good enough for me, it's good enough for them.

It's the classics that's always going to be classic.

Yeah. For sure.

Because this will come out after "Midnight Snack" and the singles, so it'd be cool if we can talk about it. Is that good?

Yeah.

Okay. How do you get inspired, then, to make new music? Or you just consider yourself in this sort of Prince zone, like, "I just don't need any new music. I don't listen to new music to get inspired to make my own stuff"? Or, what's the inspiration behind the new record?

Whenever I'm working, I don't listen to anything anyway. I just can't. I need to be in my own head. I think that there's always ... I want to make sure that I'm as me as I can possibly be. Because I am a sponge, I don't ever want to be mistakenly replicating something, or ...

Sometimes you'll sing a melody, and you're like, "Wait. Where'd that come from? What is that? I know that's something." There's a purification process that I think I go through, which is really just silence. I go through silent periods. When I'm writing, that's the best way for me to just make sure that I am solely doing me. Whether it's good, bad, or indifferent, at least it's me.

"Midnight Snacks," is that from an upcoming record? Do you have a whole album?

Yes. I am working on a record. "Midnight Snacks" just is ... It's a few things that I did that were in my head at the moment, and I was just like, "This is sort of how I'm feeling." It was just wanting to bring that '90s sort of ... Just like I said, the good times, is this just what I was thinking, and I was feeling it. I was like, "Let me just write this really quick," and it was a fun, not to be analyzed ... It's an easy, just, fun-feeling record.

Yeah. It's great.

But kind of a prelude to all this stuff that I'm thinking about and working on.

Obviously the first thing that I, when it came on, other than, "It sounded great," was, "Kelis is going back to beats," because obviously Food was quite ... Dave Sitek is one of the most future-thinking, amazing-

I adore him. He is, a hundred percent. He's a genius.

Yeah. There's nothing traditional or old school about Dave, but it was a more organic sounding, live instrumental record. Now this is like, "Oh, cool." That, like I said, my first thought was, "Kelis has gone back to beats." Is that the flavor of this record? Like you said, the '90s?

Yeah. Sort of how I started, I think. Yeah. That's definitely where my head's at. There's a void, and so, for me, I feel like wanting to fill it for myself, and wanting to just sonically get back to when I felt stuff musically. This is just the teaser, the amuse-bouche.

The amuse-bouche, which is definitely a really shitty segue. I mean, I have to ask you because the last record was Food. This is "Midnight Snacks"," which could be interpreted in any number of ways. But I guess you could say even back to "Tasty," "Milkshake," this isn't some new thing that there's been this food.

No, I didn't even realize it though, until someone said it to me a year or two whatever ago, they were like, "Yo, you always got food references." And I was like, "Do I? Oh, yeah, I do." "Sugar, Honey Iced Tea." I don't know. I think it's just because, well, obviously I'm greedy and I like to eat, but I think it's the most carnal thing, right? And when you think about music and food, it's one of those things you crave, right? Food's a really tangible way to describe that.

Yeah, when it's done in the right way, it's sexy because you're thinking of all the same impulses and senses that you would get from whatever.

Exactly.

And then I didn't realize you intentionally going for a bit of a fun, sexy '90s thing on it, but it made me think, did you ever cross paths with Aaliyah? I can't remember if her tragedy happened before you were big or whether you ever ran in the same circles or came around each other.

Yeah. I had just seen her for the Grammy's that year. We'd seen each other a few times and met. There's too many artists right now, but back in the day it was like high school. So you knew everybody to a degree and it became this very incestuous thing. We all knew each other and ran in similar type groups and things like that, so we always crossed paths.

Yeah.

For sure.

I never really thought about it, but there's quite a few parallels in what you guys were doing in that era. I don't have any good segue for this, but you just had so many good quotes and shit, I just thought we could just bring up a couple of them because they read almost a Confucius artist, way thing. You said when people come up to you and say," Hey, I want to get into the industry," which already sounds crazy to me. "I want to get the business. What's your advice?" And I'm like, "Dude, if you have to ask then you shouldn't do it. It's not a question. It just is."

I literally still say it. I say it all the time. Because it's so annoying. People ask the most ridiculous questions. But that's the thing, right? Now it's different, but back then when people would ask, "What advice do you have?" I don't have any of advice. What do you mean? This shit is hard as hell and it's hard, it's exhausting. And if I could do something else, well, I probably would because this is the whole point, right? It's about that pull. It's like if you don't feel it, like you're going to die, then you should do something else. It'll be easier.

It's true. Because even though that quote was from 20 years ago, it feels very much like your career is almost, like you said, the pull. You just got on a freight train and no matter how many times it swerves and crashes or has these wonderful successes, you can't really fucking help it. I mean, you've had success in other jobs and other things, but you are stuck with it.

People are like, "How do I do it?" I'm like, "I don't know." I'm like, "I hate this conversation."

Intentionally or not, Kelis really did throw herself on the sword for her art. I mean, she had to hear it to no end from the label people who told her, her music wasn't "Black music". And then, she did all these wild things that were definitely a no go in hiphop and R&B at that time. I mean, we live in this post-Yachty, J Balvin world where you can be as colorful as you want and express yourself, but you have to remember how nutso it was to dye your hair green back in 1999. And she did damn near every color of the rainbow. I mean, it was so futuristic, but it also meant you got labeled a weirdo and now, the kids of the weirdos as she calls them, some of them even named Kelis for her are coming up to her at the coolest festival around some 20 years later. I mean that really is beautiful.

This is a good one too. "Pop stars have to be perfect all the time. An artist is allowed on occasion, to suck. I'm not trying to please the masses, it's not going to happen, so I don't try." That one really perfectly sums up the difference. I've never thought about it in that way, between being a pop star and an artist and Bowie, and fucking Picasso and everyone has a shitty period, a shitty record, they would never get to the good stuff if you didn't have that fall off.

Well, because I think that's the thing, right? I think we've gotten so we want to love everything. We want to like it. I want to heart it, I want to like it. I want to thumbs up it. And so, instead of being like, "Yo, that's a real person and I buy into them because I like that person," right? It's like, I like when they suck, I like when it's a mess. I like when it's hard, I like when they're strung out, I like all the things about it because I like them.

As opposed to you're pleasing me right now, instantly, constantly. Please me again, again, again, again, again. That's sick, deranged when you think about it, you know what I mean? First of all, who wants to do that? Who has time for that? Who has the energy for that? I mean, I know I'm not going to be great all the time, who could be, right? And be genuine and be honest.

To do that, there's certain things that come to mind that you either have to hit a little bit of this lowest common a denominator, so you know that you can reach a lot of people and you know that you're distilling your stuff or you just have to have this maniacal, I'm going to constantly only work and do cameos with the biggest and the best people. There's a desperation.

But don't you feel like that? There are artists like that though. There are performers like that, and great. Good, great. I'm glad for them because it means I don't have to. Do that because I'm not going to do that. I don't even have it in me. It's just so not who I am. I think that they care so much and that's, again, great for them. I couldn't possibly.

Right.

I couldn't. I'm going to be bad sometimes. I'm not going to be your favorite sometimes, but it's going to be genuine. I can offer that. That's all I can offer.

This is a really amazing quote. This is from that FADER piece from 20 years ago and even though I'm English and I'm an American citizen now and a transplant, this jumped out. I mean, you said, "My whole thing is I grew up in Harlem on 1928th street. I'm an American girl." Obviously, that part, not so much for me, but the rest of it, I've been to a lot of places and I have a lot of respect for people all over the world, but I'm an American and that's something a lot of people are age or afraid to say and don't want to say, because we feel like we can't claim this country. But the only way we're going to have it is if we genuinely do claim it. That's when it actually belongs to you.

I thought that ties into so much stuff about at its very best America, American ideals, even if it's just a postcard, or a fucking Bruce Weber Polo ad, there can be things that are really beautiful about at it but the way that it's been reclaimed by the current political climate in this jingoistic way, the flag or the idea of America itself has become abhorrent to some people and I was wondering how obviously, so much has changed, especially even in the last four or five years, how you felt about that.

I mean, as a Black woman here, I think we've been fed our story and we've been fed this tale, right? And one of the things that I learned early on, I think, no one can tell you your story, you know what I mean? No one can tell you your existence and your history and we've allowed them to. And I think whether it's schools or just politics, whatever it is, we've been given this narrative of what our place is. And to me, that always just seemed so absurd. You can't hate me and then tell me where I come from. That's not logical. But I do know where the hell I come from and it's not because someone had to dictate it to me, but it's because this is who I am. This is where I started. This is where going to finish.

And I think I became hypersensitive to that in traveling. You leave the country and you realize as worldly as I am, and I am probably as worldly as it gets, I've been everywhere, I've lived everywhere, but I am an American. And I think when we talk about pride in our country and pride in that, there's so much baggage that comes with that, right? There's so much ugliness. There's so much dark, there's much blood on this country's hands, and it is hard to say I'm an American and I claim this. But I think it's because we've been told what that looks like and what that means. But if I'm able to redefine what that is, then I'm 100% accurate, right? I am American.

I've been all over the world. I'm very much American. I'm from New York. This is my city, my land and I feel, yeah, there's a lot that needs to be, even putting it mildly, everything needs to change, but it doesn't change the fact that this is where I'm from and these are our problems, you know what I'm saying?I'm not going to win by separating myself and ignoring the facts or just being so disgusted, which I am disgusted, but I have to claim it. I have to say, "Okay, this is disgusting. This is where we're at. Okay, this is it." I can only fix it by claiming it and saying, "This is a problem that we have and we need to fix that," and I have children, right? So I want them to feel a sense of belonging.

I want them to feel a sense of ownership, which is one of the big reasons why buying land was so important. When you look at our history here in the United States as Black people, as Brown people, people of color here, it's funny, when I first went to the UK and they were like, "This is all the Queens' land." I was like, "Huh?" They were like, "It's all the Queens' land." You have to ask permission to go hunting, or shoot, or buy land. When you buy land it really goes back to her in 100 years or whatever the rules are. I just thought that was strange. I was like, "That's so odd." I was like, "What? That's so bizarre," right? Being an American, for me, I know that as Black people, we're always attached to the land. We were taken from the land, we were brought to the land.

We had to till the land, grow the land, we had to fix the land, it was always about the land. So for me, the smartest thing and the best way to claim something is to buy some damn land, so that's what I did. I want more land. I'm like, "More." I'm like, "How do I get more?" Why? Because I want them to be able to stand two feet on the ground and be like, "Yo, this is mine." You know what I'm saying? If all else fails, this is mine. This is my land. This is my country. These are my rules.

And so, that to me is huge and it's really important, especially as a Black person here in the States, because so much has been taken from us, so much has been misappropriated and we've been told so many things about us culturally that are ridiculous and not true. And so, to me, it was always about the land. So, yeah, this is my country and people don't have to like it. It still is what it is. You know what I'm saying? You can't be mad now.

Do you see yourself happy there on the farm? Is that where you're going to stay for a while?

For now, yeah. I can't say that this is it.

Yeah.

Especially being on a farm and how we've so changed our lifestyle in the past two years, I'll never move back to a city. That'll never happen. Why would I give all this up? Wherever I'm at, I will always be on land behind a gate, growing my own stuff with my own set of rules and jurisdiction. I'm like, "I declare myself sovereign," okay?

So we remembered about four years ago I was dating a girl who was a huge, huge fan of yours and also was having her birthday and I was like, "Oh, I know Kelis and maybe I'll see if I can get in touch with her and see if she'll come cook and chef and cater the birthday." And it was at my place when I lived in Los Feliz, and I remember it was so exciting and I was happy to see you and I have this amazing Polaroid of you in my kitchen cooking. But I think I was partying a lot in those days and probably traveling a lot and all I remember is just sitting down for a minute at 10:30 PM, the food wasn't out yet and then, waking up in a chair at noon the next day and I completely missed everything.

That's sounds about right. Everyone was like, "Where's Mark?" I'm like, "I think he went upstairs to sleep."

I think maybe someone put me to bed, but I was eating your cornbread. I was eating cornbread for the next week. So even though I missed, there was an amazing barbecue, honey pineapple glaze thing in the kitchen.

Yeah, it was fun. It was. I actually vaguely remember the menu, but there was a little bit of dim sum and we did a brisket, that's what it was. It was this dope brisket, yeah.

I was eating the brisket for a long time and everyone was raving about the food and nobody could believe it was actually you and you were there, but I totally fucking missed it and I felt like an idiot.

I remember I was like, "Mark, I think is sleeping."

Yeah.

They were like, "Should we wake him up?" And I was like, "I don't think so." I was like, "No, he's sleeping. Leave him alone. He's fine." I'm like, "I'll see him another time."

I can't even remember if there was a cake. You'd have to tell me.

That was funny.

That's pretty rad. I mean, we covered so much and you're so smart and funny. Is there anything else with the new record that we missed?

No, I mean, new record's coming and I think it'll actually be out by the time this comes out.

Cool.

You should come back out to California and come to dinner when you're awake.

I'd love to. And are you going to tour soon? Are you doing some dates or festivals?

I don't know. I don't think so.

Okay.

I'm just writing and getting all that together.

Okay.

There have been a few things, but I feel like it's just all so spread out and weird still. So I'm not super motivated to do that. I think probably top of the year, yeah.

Okay. Well, I'd love to send you some music or I don't know what phase you're at...

I would love that actually. It's actually crazy, in all these years, we've never done anything and I've we've crossed paths so many times.

I know.

It'd be dope. It'd be fun.

This whole interview was an elaborate ruse to get you to collab on a track.

You could have just texted me or something. But, no, I would love that. I mean, that would be awesome. I'm in a good place and I'm still in the beginning stages, so it doesn't really have a form, so it could be anything really.

I'm in a full '90s zone as well, so if that's where your head's at, that might be cool.

Well, that's good. That is a good place to be. There's no other place really I'd rather be right now, so that would be dope. I'd love that.

All right, great. Well, thanks so much. It's so good to see you.

Thank you so much. You too, man.

All right, bye everyone.

Okay, later. Bye guys.

There it is. Kelis. So fucking smart. So cool. It's really been a pleasure. Take me out with the fade.

The Prisoner Wine Company is an official sponsor of UNCOVERED. For a limited time, take 20% off & get Shipping Included on the star-studded Prisoner lineup by using code: UNCOVERED at theprisonerwinecompany.com/uncovered.

Offer valid on first time online orders only for U.S. residents of legal drinking age through 12/31/2021. Rebate requests from alcoholic beverage retailers, wholesalers, or anyone suspected of submitting fraudulent requests, will not be honored or returned. Limit 1 offer per household, name, or address. For more information, contact customerservice@theprisonerwinecompany.com. Other exclusions may apply. Please enjoy our wines responsibly.