The four or five employees of the Marlboro Club in Ilfracoombe, a seaside destination in Devon four hours south of London, were the first to tell me that they had never, ever had anything like this come to their town. Damon Albarn, front man of Blur, architect of Gorillaz and one of the two or three biggest rock stars in England would be playing there—right here at the Marlboro Club—with his new band in a matter of hours. Not only that, but the bassist would be Paul Simonon out of the Clash, the drummer would be a much ballyhooed Nigerian fellow called Tony Allen, and Simon Tong, who was in the Verve, would be on guitar. As the band kind of muttered around and then sound checked—that’s Paul Simonon, Best Looking Man in England, right there—the excitement and anticipation weren’t just palpable, they were impossible. It set everyone at ease though that the band members were just kind of walking around, a bit puffy with sleep after the pub gig in East Prawle the night before, smiling and nodding an “alright” at folks as they paced the dingy carpeted floor. Soon everyone was going about his or her business, readying the club for the show. If anything, the most surreal part was how close to natural it felt being among these giants. Albarn bummed a cigarette and mentioned, with a melancholic love in his eyes, his affection for the colorful bunting that a friend had strung for him, which now hung above the instruments onstage. “Bunting is quite English,” said Hannah Claxton, part of Albarn’s management team. “It’s also quite African,” added Albarn.

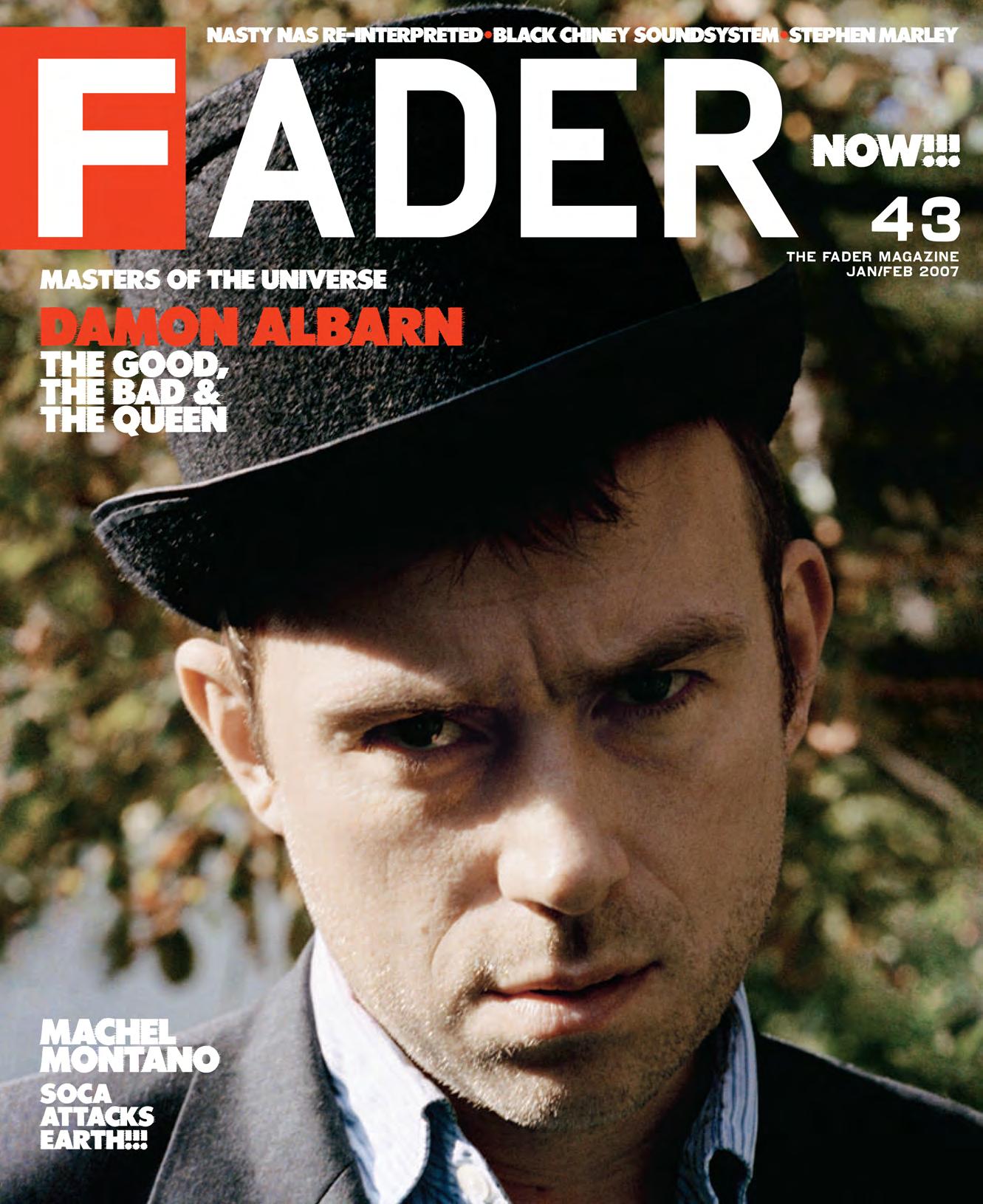

Some five hours later, the band was stashed away in their tour bus and the same surreal energy bounced around the now-full pub. Tickets had sold out in ten minutes. The kids—and the 20-, 30- and 40-somethings—were jumping out of their shoes with anticipation. When the band walked in and took the tiny stage, the crowd was ready to explode: the album The Good, The Bad & The Queen wouldn’t be out for months, so nobody knew what to expect, but it was real—they were right here right now. Albarn looked rakishly handsome with his front tooth all but missing and an outlandish top hat on (he had permanently borrowed it off a bartender two towns back when the pub staff showed up to the gig in circus outfits). Simonon looked like the toughest motherfucker in England with a porkpie hat and a vicious boxer’s scar across his nose. Surely this band was going to tear the roof off the Marlboro Club and burn the four walls down with a flicked cigarette butt on the way out of town.

Then the music started. Albarn was at an upright piano back and left of center on the cramped stage. Tong played a spidery guitar figure and Albarn sang softly—even sadly—Come the day/ You see the sun/ Hit the arch/ A history song. It felt good when Simonon brought in a bumping and skanking reggae figure and began stomping, bearing down on the kids in the front row, looking them in the eye and pointing the head of his huge bass at them like it was an elephant gun. It felt even better when Tony Allen came in with a feather-light but somehow gangster shuffle on the snare. Then, as they all chanted La La La/ La-la-la-la-la-la-la and began to let those instrumental parts abstractly unravel, it ended. The mellow start—especially with Simonon egging on all comers like a prizefighter—only pushed the crowd closer to bursting, wanting the band to fucking GO IN. When the show ended after an hour, the album having been played straight through, there had been countless hauntingly amazing moments, but what had they just seen? It was exciting and it occupied some uncharted space between moods and styles and was surely something, but what it was definitely not was Blur + the Clash + afrobeat. And that was not exactly disappointing, but definitely a bit mystifying.

Ever since the end of Blur’s preeminence at the close of the ’90s, Damon Albarn has defied expectations, or, more accurately, run circles around them. He has maintained a definite presence in the English public’s imagination, but only while simultaneously surrounding himself with a world of his own making that has eventually come to defy all of that public’s reference points, almost without them noticing. First he founded Honest Jon’s Records—a label he runs with the people behind the London record shop of the same name—and began putting out music from around the world, including his own Mali Music in 2000, which featured him collaborating with West African musicians. Next he formed Gorillaz—a cartoon band that makes real music—with visual artist Jamie Hewlett. Even with the wild success of the self-titled debut Gorillaz album in 2001 and the seven-times-platinum explosion of the follow-up Demon Days in 2005, the group’s famous mastermind happily evaporated amidst the multimedia onslaught. Albarn had surrounded himself with Africans, record store dudes, cartoons, obscure or dated American rappers, Miho Hatori, Ike Turner, Shaun Ryder, Dennis Hopper and beyond, but even the millions of people who bought the CDs and listened to them over and over didn’t seem to wonder—much less actually come to understand—what circles, exactly, the former hero of Britpop was now moving in. Behind those cartoons, the most improbable sounds and collaborations seem natural enough, and with songs and videos that good (even if they are pretty dark), who was going to deconstruct them? In America, meanwhile, where Blur’s success had been modest enough that Damon Albarn as celebrity persona had never quite crystallized, there was even less reason to look behind the scrim.

Regardless of what listeners have attended to, the story of Albarn/Simonon/Allen/Tong and their record The Good, The Bad & The Queen is no less fantastic than that of Mali Music or Gorillaz. “The last song that we did together as a four piece in Blur was ‘Music Is My Radar,” Albarn says, while sitting by the loading dock of a historic London music venue called the Roundhouse. “The chorus of that song is ‘Tony Allen got me dancing.’ So Tony heard it. Somebody obviously told him that there was this…person that was singing a song about him.” Allen, who, as Fela Kuti’s musical director and the leader of Africa 70 is easily one of the greatest drummers alive (“The African Art Blakey,” says Albarn), wanted that same person to come to Nigeria to sing on a song he was working on. Albarn agreed, and although Allen was at first nervous that Albarn might not be able to relate to his often elusive drum patters, he was ultimately thrilled with the result. “After that he became my friend,” Allen says. “Damon is a character, and that made us even better friends, because I like characters. Later—this is three or four years ago—I said to him, I look forward to when we can do something together from scratch. He said, Okay, Tony, why not? But he was too busy then.” One day, according to Allen, Albarn called the drummer at his home in Paris and said, “Okay Tony, I’m free now. Free, free, free. Let’s go for it.” As is his way, Albarn wanted to record in Nigeria, so after some initial writing sessions in London, a studio was arranged and the pair set off to Lagos.

When I ask Albarn to try to pinpoint the source of his interest in Africa, he describes his early childhood in the wildly diverse neighborhood of Leightenstone, East London, and the effect it had on him until he moved north to the homogeneity of Essex at age nine. What actually brought Albarn to Africa for the first time, however, was Oxfam, the London-based anti-poverty group. “About ten years ago Oxfam invited me to do one of those ambassadorial things to Mali, which I was not into,” Albarn says. But instead of rejecting the charity outright, he proposed a different sort of trip. “Coincidentally I’d been listening to a lot of Malian music around that time, because I’d started to get to know the people in Honest Jon’s records and they were feeding me records every other day. So I said I’d go with a DAT player and instead of going to orphanages—although I did go to a couple—I just wanted to travel around and meet all the musicians I’d been listening to. And Oxfam made that happen. Out of that came a record eventually, but more importantly, it changed my life. It was a crossroads for me and I went opposite to the way that maybe a lot of people from my generation went at that point. I lost the fear, the need to hold onto the past. And I fell in love with the process of making music and adventure and going to new places and getting to know people. And I suppose that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.” Between his own projects and the Honest Jon’s projects he has overseen (“You Americans would call it ‘Executive Producing,’ I call it…facilitating,” he says), Albarn has recorded in Mali, Nigeria, Algeria, country A, country B, county C.

Although the chapter in Albarn’s adventures that resulted in The Good, The Bad & The Queen began with the Tony Allen sessions in Lagos, it would be years before the project became the record that I first heard live at the Marlboro Club in Ilfracoombe. In Nigeria, Albarn and Allen put together a band that combined some of Albarn’s collaborators from England (including Simon Tong) with two of Allen’s former Fela bandmates, as well as some local musicians—some 15 players in all. By all counts the sessions were productive, but Albarn decided to scrap them, with the input of Demon Days and eventual The Good, The Bad & The Queen producer Danger Mouse.

“We had finished the Gorillaz record and I knew Damon had some stuff that he had recorded in Nigeria,” says Danger Mouse, aka Brian Burton. “He asked if I would like to work on that project, and my reaction was that I thought there was some great stuff in there, but what I thought was great was in a different direction. I agreed to initially give it a shot as long as he was okay with the fact that we wouldn’t necessarily stick to the direction it was already going.” Danger Mouse and Albarn convened in London and began going through the demos, chopping out pieces, writing new demos, exploring new sounds. Allen and Tong joined them, and eventually they began jamming with bass players, looking for the right fit.

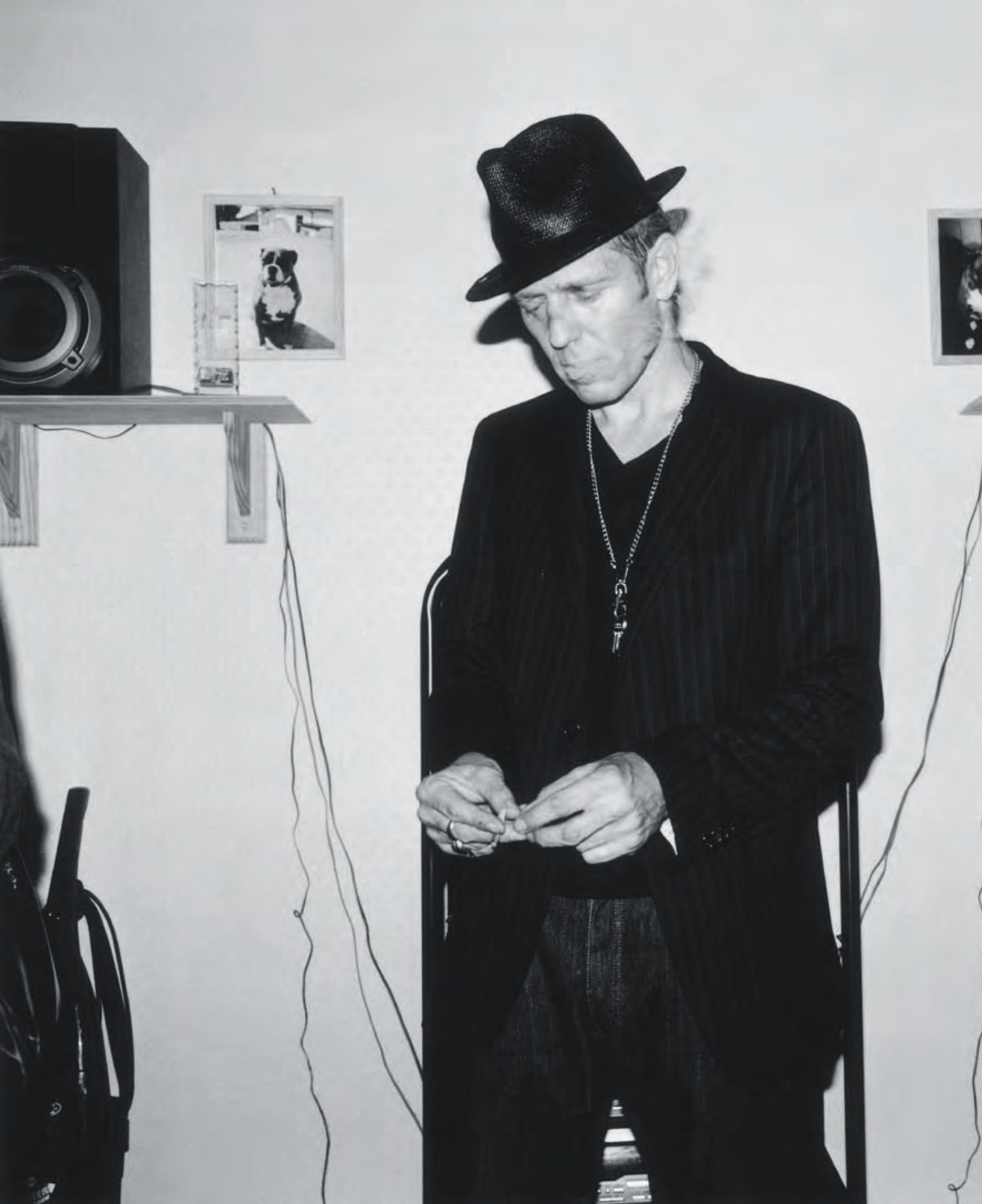

When I ask Albarn how the hell he managed to convince the Clash’s Paul Simonon—who had given up music entirely some 15 years earlier for the visual art world—to pick the bass back up, he responded with a laugh and said, “I rang him up and said, Do you fancy playin bass?! And he went, Yeah! Why not?” Albarn’s confidence, his directness, his incapacity for bullshit and pussyfooting that complements his relentless need for experimentation and collaboration is one of the most immediate characteristics of his personality, and probably also the one that has allowed him to continue to succeed after the blast of inspiration and achievement that was Blur in the ’90s. Without pretense or preciousness, he seems to treat everyone equally. It’s what allows him to laugh and abandon a song when Danger Mouse ruthlessly calls it “too Lion King.” It’s what allows him to form a band with a hero of his—someone he calls “the African Art Blakey”—and then allows him to explain to that same hero, without fear or hesitation, why his drum parts have been chopped up, rearranged, sometimes even removed from a song entirely.

When I was in London with The Good, The Bad & The Queen, one front page headline for a column in The Guardian read, “WHO’S DOING AFRICA’S PUBLICITY? I MEAN, COULD IT BE ANY HOTTER?” Albarn, meanwhile, told me about a program he started that, rather than a press opportunity, is an opportunity to bring musicians of all stripes to Africa to meet other musicians—to hang out, drink beer, maybe jam together—for the sake of all the musicians involved equally. Although Albarn believes that consciousness- raising celebrity ambassador trips further separate the third world from the first and insists that we have to find a new model, he is not delusional about the power of his very different kind of program, or his music. “The point is,” he says when asked about the oblique political bent of his songs, “I don’t think a lot of people get what I try to do in my tunes, which is to kind of try to express my sadness, my melancholy about the state of politics. I don’t necessarily point and say, ‘That’s wrong.’ But it’s the melancholy I feel about what’s wrong. Maybe it comes from the Beatles really. Maybe John Lennon is the man who invented the melancholy that I’m just sort of playing out.”

The culmination of the run of three warm-up pub shows that Albarn, Simonon, Allen and Tong had done in the South of England was a much-hyped, BBC-sponsored (and broadcast) show at the Roundhouse that would be the official debut of The Good, The Bad & The Queen. Under Danger Mouse’s guidance, what started as a big band project in Nigeria with an emphasis on afrobeat, had become a much more settled, psychedelic, loose group with wide-open spaces, dizzy organs, electronic tinges and dubbed out drops. The addition of Simonon to the band had brought not only a messily aggressive punk and reggae underbelly to the rhythm section, but also a new lyrical direction for Albarn. “The fact that I was supposed to be putting bass on the songs that were evolving was becoming more distant,” Simonon says, “and a whole new thing was developing through conversations and books that Damon and I both enjoyed about London and local landmarks.” The result is an album about England in general and the North Kensington area where Albarn and Simonon live in specific, and many of the songs feel like oblique requiems both for the character of the country and neighborhood that once was, and that which it could, but might never, be. This, then, is the sonically and emotionally complex record the band is charged with selling to another virgin crowd—another crowd that had probably come with something like Blur + the Clash + afrobeat in mind.

The show began well enough, but on “Kingdom of Doom,” the most rocking song on the first half of the record, Simonon’s bass cut out and the band had to start from the top. Later, Simonon and Allen were having serious trouble locking in with one another. The group was in the midst of a minor meltdown, and was losing the increasingly perplexed audience. Finally, after an uninspired first verse of “Three Changes”—a dark, fed up, circus-storming tune that is the live show’s apex—Albarn stopped the band in the middle of the song, furiously yelling, “We played that shit! Sometimes when you’ve only played four gigs, you’ve got to refocus, and we’ve got to refocus and be the band we know we are.” As the show slipped out of their fingers, Albarn responded by scolding a band full of legends. Then he put them on his back, counted “Three Changes” off and roared fantastically as they kicked the song off from the top.

More than anyone else at his echelon in the musical landscape with the possible exception of Björk, Damon Albarn has put his money, his name, his talent and his rolodex to use, dreaming up his fantasy projects and getting first on the phone, then in the studio to make them happen while many of his contemporaries have self-destructed, played it safe, or disappeared as they’ve aged. In the case of Gorillaz, Albarn’s hyper- ambitious risk was an unqualified success of such magnitude that it has opened up even more opportunities and resources. A feature-length Gorillaz film is in the works, as is a Chinese opera in collaboration with Hewlett and Chen Shi-Zheng called Monkey: Journey to the West.

But that night at the Roundhouse, Albarn and his newest creation were under fire, and it was not clear how they would respond. In our interview, Simonon said this band, given the age of its members, wasn’t gonna be doing any leaping and swinging around. But that night, given the circumstances, Albarn jumped and kicked and stalked the stage and stood over the crowd and dared them to take his motherfucking band on. Although he must be used to success by now, he wasn’t assuming it, and he proved he was willing to fight for it. The Roundhouse is a massive old venue that’s shaped like an enormous circus tent, and as a siren squall of a synthesizer wailed the outtro to their second run through “Three Changes,” as Tony Allen laid down his heaviest 4/4 groove of the night, as Simonon locked in, Albarn stormed around the stage in his top hat, looking like the Master of Ceremonies under the big top of the Greatest Show on Earth. He looked like he was summoning his darkest, most mysterious powers, and, with the help of his troupe, performing his most subtle but daring act yet.