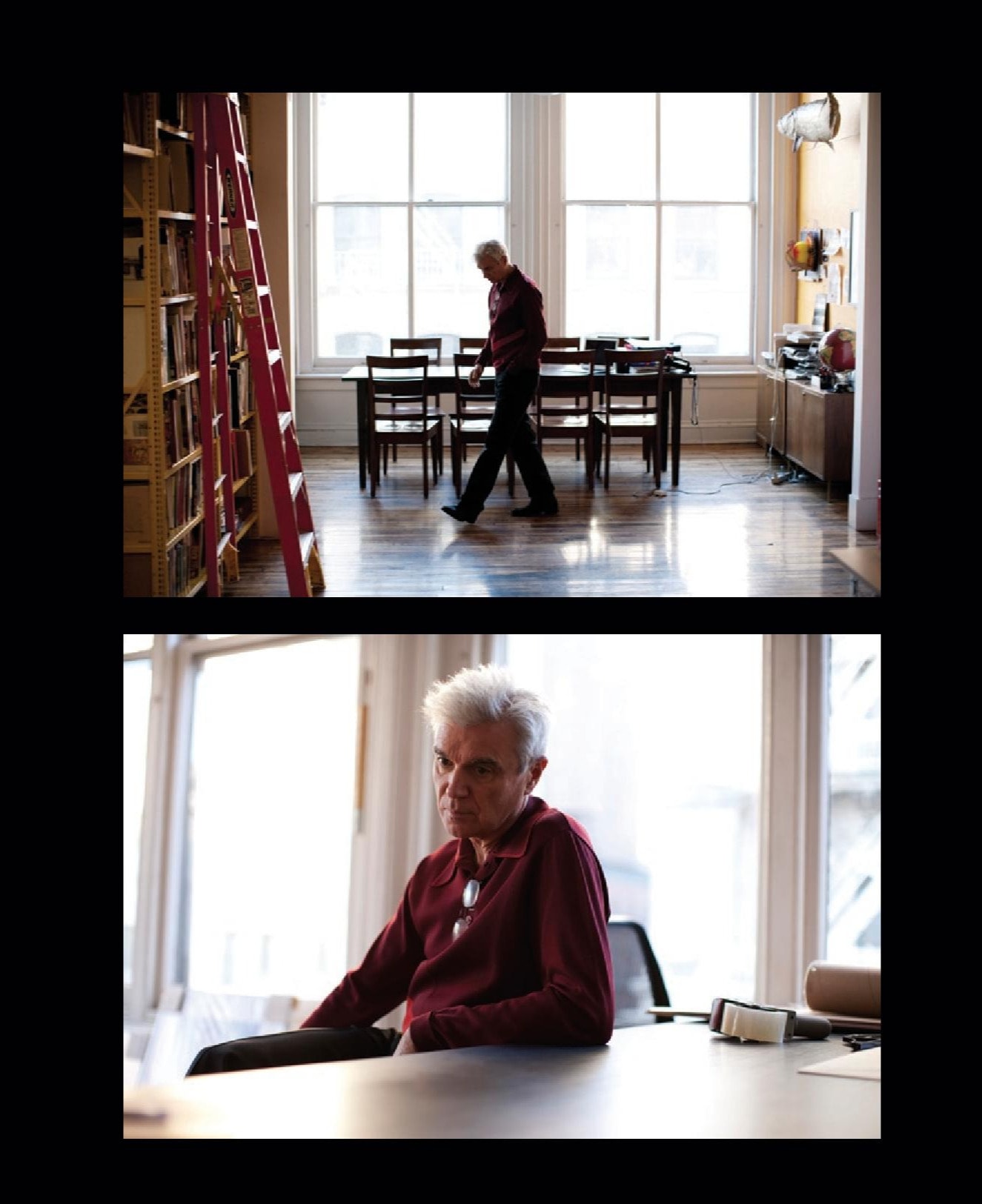

Entering David Byrne's Manhattan studio is a bit like walking into the office of the world’s coolest anthropology professor. The SoHo loftspace is littered with all manner of cultural ephemera. There is a wall of art books cozied up to a series of anatomical models from the ’50s, a handful of original paintings (some of which appeared on Talking Heads album covers), a small pyramid of canned artichoke hearts, various bicycles, a wall-size map of New York City and a bookcase filled with kitschy toys, a few of which are delicately balanced on top of a trophy from something called the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

At 56, Byrne is one of the few artists of his specific generation—the grimy, druggy, CBGB-powered Lower East Side New York of the late ’70s—to maintain the kind of visionary status that helped make him famous in the first place. Throughout his years with Talking Heads, his various solo recordings, collaborative projects and his work as a visual artist, writer, curator, record label head and bicycling impresario—Byrne remains a kind of artist’s artist. While too many of his peers have retired, died, faded from view or resigned themselves to making a living trading on the nostalgia of their early work, Byrne remains an iconoclast—doing a little bit of anything and everything with whomever he chooses.

Having just released another career-defining album—the Brian Eno collaboration Everything That Happens Will Happen Today—and embarked on a globe-circling tour, today’s David Byrne is a far cry from the anxious art school dropout seen jittering through old concert films. These days he is happy and relaxed, genuinely interested and infinitely interesting.

The FADER: Does it feel weird to be the icon?

Byrne: Oh yeah. It’s pretty weird. You just go about your business trying to do things. I don’t think about stuff like that very much.

You don’t strike me as someone that’s very interested in nostalgia.

No. I only get nostalgic for things like old neighborhoods. I get nostalgic when an old building I like gets torn down.

When CBGB closed, everyone got very sentimental. Don’t you think sometimes it’s good to just let things die and remember them for what they were?

Yes. Just let something else happen now, you know? That bar stayed pretty vibrant for a really long time—longer than most places. There were some other good scenes to spring from that place in later years—particularly the anti-folk stuff—but most emerging music had long since started to happen elsewhere. It remained a good place to get cheap beer right until the end, but it hadn’t supported a vibrant, emerging music scene in a long time.

You’ve always been super cognizant about emerging music.

Oh yeah. It’s a bit overwhelming. All the mp3 blogs and stuff—I love it. I think most people my age don’t really feel like they have the time to fully explore, but it’s very worthwhile for me. I find so much new music really inspiring.

You appear so much more at ease these days, so much less anxious—both on stage and in your music.

Yeah, that’s true. I’m certainly much less anxious than I was back in the day. For some people, that’s not as good. For some people, the anxiety and the tension of the early performances was the thing they really loved. Still, for the person experiencing it, it’s not very much fun. I’ll admit that anxiety and angst can certainly produce some interesting work, but it’s not the only way to make music. I’m a lot less angsty and anxious than I used to be, but I’m also older now. I’ve been through some ups and downs, you know? I certainly care a lot about what I do, but I’m also not as obsessive and crazy as I used to be. I’m much more relaxed. I don’t think the work suffers as a result of me not obsessing over it and micromanaging every tiny detail of everything.

Your current tour focuses specifically on your work with Brian Eno, including songs you recorded with Talking Heads. How has your relationship to those older songs changed over the years?

I’ve played some of those songs fairly recently, so for a lot of them it’s not really that strange to revisit. There are some songs—“Air” from Fear of Music—that I haven’t performed since 1979, which is very odd. There are a few of them that conjure this ghost in my mind of where I was and what kind of weird places my mind would go to when I wrote songs. A song like “Heaven,” for example… I remember that Jerry Harrison worked on the verses a lot for that song and we really wanted it to be like a Neil Young song, which is kind of believable. The choruses were written by me and I wrote them by saying the words over and over into an early Walkman—one of those ancient, giant versions—and I’d just repeat the words over and over again until I could figure out the melody. It wasn’t intuitive at all. It was just some weird thing that happened. When I think back now it just seems like the weirdest way to write something. I read somewhere that Bon Iver does something similar—just repeating the melodies over and over until words start to emerge.

Has your creative process changed?

Well, I’m sure it has changed—but I’m not sure how. To some extent, when you are younger, when you sit down to write a song it’s a slightly new experience each time. You are figuring out whether or not you have the skill to do it. After a while you realize that you have the skill, but that it’s gonna get stale and repetitive unless you continually throw yourself out of the comfort zone and try doing things that you don’t quite know how to do. It has to keep changing.

Do you feel more comfortable in the role of collaborator than you do as a solo artist?

It’s definitely easier to be a collaborator. I obviously like writing stuff by myself as well, but it’s easier to work with someone else. You know, sometimes you start something and then there’s someone else there to finish it, or you have someone else’s material and the initial direction has already been decided. It saves you from sitting in front of an empty computer screen or a blank piece of paper and trying to figure out what to do first. It’s nice when the train is already in motion and all you have to do is jump on board.

Young bands generally have a much wider, more fluent musical vernacular these days. They’ve grown up with a broader frame of reference.

I love that. I think it’s so exciting. There were a couple of decades there where things were becoming really segregated, in which musicians would only reference other artists who were doing the exact same thing. It’s much more exciting to hear music that pulls from all these different genres and styles. I’ve always been a champion of that.

You are in the midst of a lengthy world tour right now. Do you enjoy touring?

I enjoy touring now, but I don’t think I always did. In the early days of Talking Heads I really had to get on stage and perform because I just had to do it. It was the only way that I could really properly express myself. I was very socially inept and the only way I felt like I could get my point across was to get on stage. Then later, I went through a period when it became slightly more joyous, but I was still pretty angsty and very much, It has to be done this way, and I’m sure I wasn’t the most fun guy to work with. Nowadays it feels like a total joy to just perform. Maybe it’s because of the musicians I surround myself with and the technical crew I have, but mostly it’s just because I still enjoy the physical act of singing. The physical release of it. The pleasure of getting a good groove going. It’s not like I want to be like Bob Dylan, doing it every day for the rest of my life, but when I do it now it’s a total pleasure.

When you see images of yourself when you were younger or old performance footage, is it hard for you to watch? Do you just think, Oh, there’s that guy again?

Yeah, it’s just that guy. I feel so distant from most of it. It’s just, Look at that guy and look at what that guy was doing. Sometimes I’ll think, Yeah, that was pretty great but I could never do that now. Meaning that there were certain things that I wrote that I would probably never come up with now. They just sort of tumbled out of me. Now I’m a much different person. I’m not thinking about the same things.

You’ll be doing another “Playing The Building” installation in London, right?

Yeah, it’s at the Roundhouse in London, which was once an old train station. It’s actually the first place that the Talking Heads played in London. We played with The Ramones. It was the first US punk show over there. The building has been newly renovated and it’s a really amazing space.

And your book, The Bicycle Diaries, is out this fall. Did you ever imagine that your love of biking would become such a big part of your creative life?

No, not at all. The book is a record of things I’ve written over the past 15 years, biking all over the world in different cities. I started writing as a kind of therapy, usually about things that were pissing me off. Some personal things, some more socially-related things. For a long time I felt like biking was this cause that I’d taken on. I knew it was this really fast, cheap way to get around. It was easy to get around the Lower East Side and see shows and meet up with friends. It seems like a fascination that was much too nerdy for anyone else to really get into. It’s still a pretty nerdy thing to be into, but other people seem to like it now as well.

What about your long-in-the-works Imelda Marcos musical?

It’s coming along. I spent about a year going around to different theaters trying to get money to stage it somewhere, but no one would really go for it.

Because the idea was too weird?

It’s obviously not too weird. It’s me and Fatboy Slim. It’s songs. It’s not really weird. If it were more “arty” we might have gotten further. The songs are actually quite catchy, but they aren’t catchy in a Broadway sort of way. It’s neither fish nor fowl. So, instead of staging it, I just decided to finish it as a record. I invited all these different people to sing various songs. Sharon Jones did a song, Tori Amos did one, Santi White—there are 22 songs.

Are you doing any design work right now?

Not at the moment, but I might be doing more of the bike racks around the city.

Do you have one in front of your own house? You should demand it.

No, but just this morning I went to buy some peanut butter and the owner of Gourmet Garage saw me and said that he wanted a bike rack out front. I told him I’d draw one up.

You seem to have a pretty laid back life in NYC. Do people bother you much or stop you on the street?

Not too often, really. I figure that if you act like a regular person then you get treated like a regular person. If you walk around with an entourage, then you’re basically asking to be treated weirdly.

Fame never felt burdensome for you?

No. Hardly ever. The only downside, as far as I can tell, is that you have to be a good, decent person.

Fame makes you good and decent?

Well, someone is always watching. You have to leave a good tip, otherwise someone will blog about it and you look like a jerk. That sort of thing. Everyone knows about the good parts of fame. You can walk into a restaurant and always get a good seat. It’s not really fair, but it’s nice.

Do you have a sense of what kind of music you’d like to make next?

Oh no. I never do. Once this tour is over and I get back home, I’ll start fooling around with some ideas. It usually takes a while to see what direction things are moving in, but eventually whatever has been percolating in my mind will reveal itself and suddenly I’ll just think, Yes, there it is!