Driely S.

/

Pitch Perfect

Driely S.

/

Pitch Perfect

Muzz may well be one of the most unassuming supergroups in the world. For a start, this is not a group of musicians coming together, Avengers-style, to combine their individual powers. Interpol frontman Paul Banks and Josh Kaufman, who has worked extensively with The National and The Hold Steady, first met while at school in Madrid, Spain as teenagers. In the early 2000s they both moved to New York to study and became friends with drummer Matt Barrick, once of influential rockers Jonathan Fire*Eater and then a member of The Walkmen, as they all enjoyed the spoils of a golden era in the city’s musical history. With a relationship that dates back two decades it is perhaps surprising to learn that they only decided to start working together officially in 2015. That Muzz’s debut album has only just dropped five years later is testament to three friends who know that life-long bonds bring with them the gift of time.

Muzz is an album that bears the tide marks of its creators — Barrick’s jazzy swing, multi-instrumentalist Kaufman’s soft warmth, Banks’s instantly identifiable baritone — but it defies easy categorization. The album lolls at a leisurely pace, never too rushed to stop and take in the view. Songs like “Bad Feeling” and “Knuckleduster” will feel familiar to those who devoured Lizzy Goodman’s NYC rock bible Meet Me In The Bathroom, slipping on easily like an old leather jacket. Elsewhere, however, washes of slide guitar, piano, and horns call to mind the roots-era sounds of Bob Dylan and Neil Young. It feels less like Muzz came together to remind their respective fans of what they already knew they could do, but rather step into their third decade as friends by melding their respective pallets into one expansive breeze.

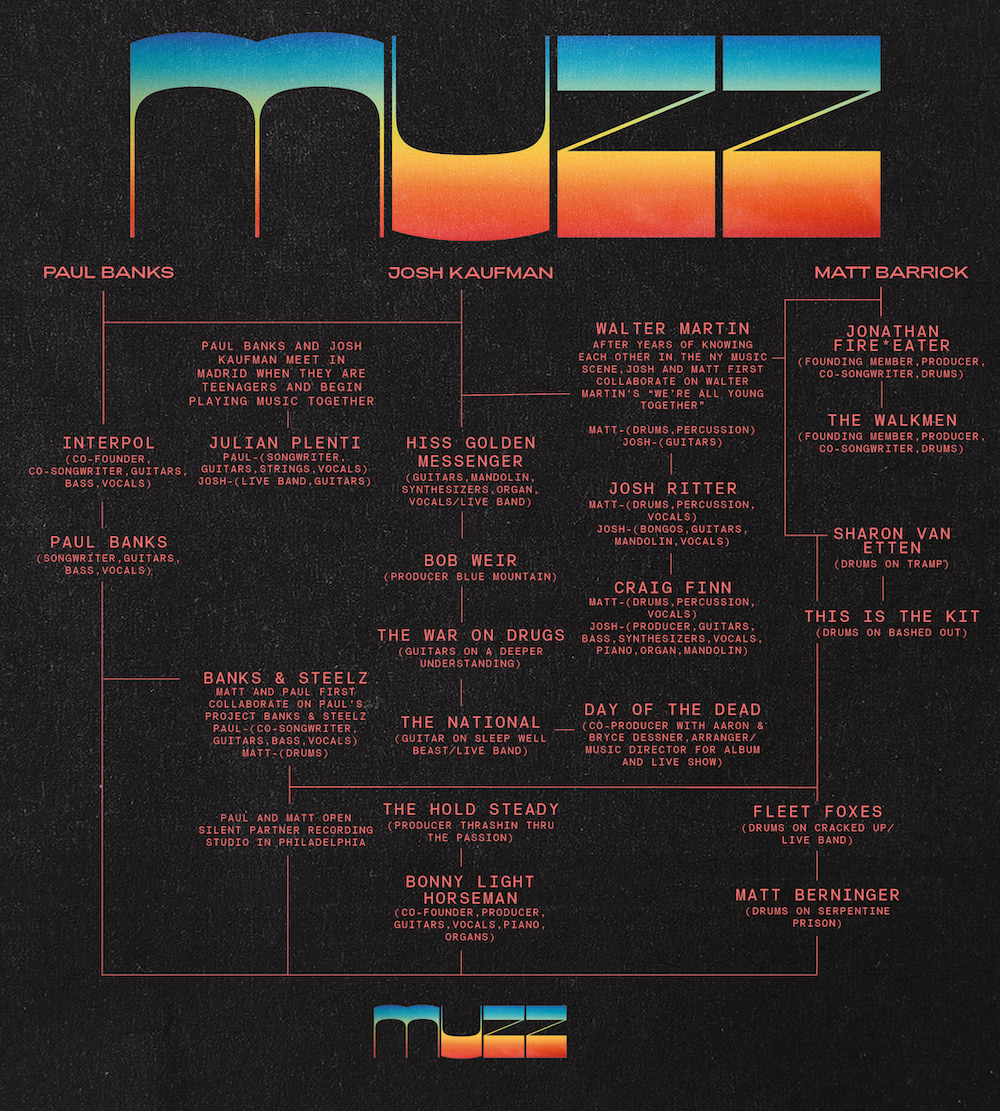

Collaboration is not out of the ordinary for any of Muzz’s three members. As you would expect from three guys who have spent twenty years playing in bands, Banks, Kaufman, and Barrick boast a rolodex of credits that encompasses many of the major tentpoles of the past 20 years of indie rock. The family tree they put together below clearly illustrates that, while Muzz might be the first time they’ve worked as a trio, they’ve often had each other’s backs on past projects. When Banks recorded his 2009 solo album (released under the moniker Julian Plenti) he turned to Kaufman to join his live band. Similarly, when he and Wu Tang Clan’s RZA needed a drummer for their unlikely collaborative project, Barrick was the first choice. Kaufman and Barrick, meanwhile, have worked together on solo albums by Walter Martin and Craig Finn. The tree shows a group who have been together in spirit for many years, even if it’s only just becoming something with a name attached to it.

Read on to hear from all three members of Muzz as they go through the family tree and discuss their favorite songs from their many, many projects.

Paul Banks

Muzz, “Bad Feeling” (2020)

Paul Banks: This one goes down real easy. When you're introducing a new band you can do yourself a mischief by using the wrong order of songs. If you hit people with the most experimental thing you did and hold off on the more accessible songs then people might never get to them. We put this out first so people could be like, "I get that song." It goes off like a shot.

Josh and Matt had put that instrumental together one day after I left the studio. I first heard it at a session at Isokon Studios in Woodstock and it really jumped out at me. Something about it made me want to put it in my pocket and carry it around with me. There’s something very minimal and beautiful about it. I started writing some lyrics that weren’t super inspired so I took a step away to avoid getting greasy fingers on the track and smudging it. Later I was in a remote part of central America where I like to go spend time and surf. I had a friend of mine out there who was taking his family into the wilderness, this totally untouched spot of paradise that takes two miles of unpaved road to get to. The guy was in such a place of elation that I was inspired by his joy at going off the grid and into nature. It struck me as an antidote to a lot of the urban feelings that characterize my life when I’m on tour and the joy was contagious. I sat down by the beach and wrote the lyrics in one take. The vocals were recorded in one take.

The FADER: Does that idea of going off-grid appeal to you?

I think there’s a yin and yang to it. My life is very different, I’m all up in the grid. It’s a bold move to just follow your heart like that. The positivity of this guy was just contagious, I guess. I don’t need to go off-grid but I like being in the middle of fucking nowhere. I just need my phone.

There’s a line in that song which stands out: “Iʼm still selling someone I forgot at 17.” What were you trying to say there?

The song has a couple of different frequencies. The beginning of the song and the chorus is dead on the frequency of that adventure and then there’s other parts where it’s like a peripheral take, almost like a film jumping from one narrative to another. This song and [Muzz track] “Don’t Call Me Stupid” have some invasive thoughts in them. Leaving them in there is fun.

Julian Plenti, “On The Esplanade” (2009)

This is one of my favorite tracks on my debut solo record. There's a lot of sound effects that I use that I was really chuffed with at the time. I remember kind of feeling like the internet was like an incredible sample bank, basically. So I believe in that song there's some kind of Indian wedding singer that I found on YouTube and then there's female tennis players. You get the percussive sound of the ball hitting the racket and then the tennis players grunting. Female grunting tennis players are kind of like the additional rhythm section in the choruses to this song, as well as this random dude singing a wedding tune. I really like the idea of found sounds in music, and I was really doing a lot of it at that time.

I'd seen Lost Highway by David Lynch and there's these amazing scenes where it cuts to a kind of VHS footage. It wasn't just the fact that it was like super eerie that someone's in this person's house, it's the way that the VHS took on this really ominous sort of quality, and I remember kind of thinking it's like a degraded form within a higher form, and by doing that, you get all the dimensions of that other form. A similar thing kind of applied to sampling, where you sort of get all the history of that sound that you're appropriating, whether it be hip-hop production or in the case of like found sounds, you get the whole world that it's from in some other format.

Interpol, “Leif Erikson”(2002)

I remember crossing Houston in Lower Manhattan on the way home from an Interpol rehearsal listening back to a tape and just kind of feeling super stoked about the trail that I was on. I also remember that Carlos [Dengler, former Interpol bassist] had played a keyboard part before we had the lyrics to that song that just really evoked like an old galleon kind of triumphantly appearing on the horizon, visible from Nova Scotia or whatever. So that's how it got the name “Leif Erikson.” I remember being in the terribly vulnerable position of about to release your debut record. As a very self critical person I remember kind of thinking like, well, at least Leif Erikson's on it, because that one I know I like, that one I know is good.

How soon after finishing the Muzz album do you start thinking about Interpol again?

We're actually tossing around some ideas now. I'm never not working. I was working on Muzz when I was on tour with Interpol and I'll be working on, well, I'm working on Interpol now, while promoting Muzz. So yeah, definitely there'll be more from that band.

Josh Kaufman

Bob Weir, “Only A River” (2016)

Josh Kaufman: Josh Ritter is an amazing songwriter that I've been playing and producing for a long time. “Only a River” was a song that Josh wrote when he was a young guy based on an old folk song called “Oh Shenandoah.” When I first started working with Weir we were discussing images of the Old West. He had spent some time on a cattle ranch as a teenager after getting kicked out of a bunch of prep schools. He ended up on a ranch with an old friend of his named John Barlow where he started hanging out with all these cowpokes, and that's some of the first music that he learned.

The objective with this record was to make this modern cowboy music, basically. And so “Only a River” was brought in to serve as one of those. It was a really emotional time for Bob. His dad was sick at the time. And for me, getting to be with one of my childhood heroes, legend of American music and founding member of The Grateful Dead. When I hear that music back, I’m flooded with a lot of emotions and memories from that time. It was an amazing learning experience, and he was super generous creatively with his time and just being a cool guy. A lot of people tell you not to meet the legends, that they'll disappoint you, but I found the opposite to be true

How did you come to be involved with Weir?

I got a call to be a music director back in 2012 for a project for The National. We were going to be backing up Bob Weir for a concert in the Bay Area that was put on through [voter registration organization] Head Count. So I got to meet Bob then, and we weirdly hit it off. I was really nervous to meet him, and then once I met him, we started talking about music and those nerves very quickly flew away. It just felt like I’d made a fast friend. Which was really cool. I hadn't had that many experiences with other musicians that were the age of my parents and was able to just speak this language with them and feel connected.

Muzz, “Patchouli” (2020)

“‘Patchouli’ was an intensely collaborative song that I don't even think we were aware of while we were writing it. We were hanging out in the studio and came back into the live room and just sat down at instruments and started jamming. Our engineer and co-producer Dan Goodman was recording it but I don't think we realized. We went back into the control room, took a listen to what we had done and thought that it was going to be a pretty amorphous sort of blob. Paul heard what we had just done and said, "I think I have an idea for a lyric." We left him alone for a half hour and came back, and that was it. That track was done just very quickly. And it was created out of our subconscious. That was the first time that we harnessed that power, the three of us improvising together and just vibing off each other in a room and believing in it. I feel like it brought the three of us even closer together, musically.

Bonny Light Horseman, “Mountain Rain” (2020)

Bonny Light Horseman is a band I have with two close friends, Anaïs Mitchell and Eric T. Johnson from Fruit Bats. The deal with this project was us trying to define these sort of transcontinental folk songs, songs that started in Africa and made their way to the U.K. and Ireland and mingled with American songs.

There was a lot of talk about different characters and finding new narratives for a lot of these old folk figures. John Henry was a big folk figure for us but I always felt the music that went along with this heroic tragedy never quite fit the lyrics. The mournful music that we came up with fit the story I wanted to tell but I could never find the right opening into the lyric to get the story right.

Anaïs and I had been searching through a bunch of old versions of “John Henry” and had found a cobbled together version of the story that we wanted to tell, but we still didn't find that first verse. At the time I was on tour with Hiss Golden Messenger. I was telling MC Taylor about this song, and I played him a little bit of it. He said, ‘I hear what you're saying, and I hear the sadness and the truth of the story. I think I have something, but give me a minute.’ He walked into his hotel room, and I walked into mine. Literally five minutes later my phone pinged. When I looked at it and he sent me the first verse. "All the miles stack, like a millionaire's money. I can't get them back and I'm starved for that honey." And I was like, ‘That's it.’ It was a long search and it came out of this circuitous path I could have never have foreseen.

The song is about this failed idea of a capitalist structure, which I think a lot of folk music tries to get at. It still resonates because, obviously, the structure that's in place in society that is meant to work against particularly people of color and working people, hasn't gone away. I think it's just, unfortunately, a very relevant story. It’s important to say "Hang on, how come this hasn't changed? Maybe we need to think about this again."

Matt Barrick

Jonathan Fire*Eater, “Search For Cherry Red” (1996)

Matt Barrick: I was probably about 20 years old [when this came out], it felt like a breakthrough for me personally, just in terms of my drumming style. In terms of the song, it all kind of started with that beat and we built a groove around it. In general, I think the song is probably a bit long - we weren't editing much at that point so a lot of it hinges on Stuart's lyrics and just giving him a musical bed to weave an interesting tale.

How do you feel Jonathan Fire*Eater's reputation has changed over the years? It feels like you got a bit more recognition following the publication of Lizzy Goodman’s Meet Me in the Bathroom

I definitely feel like that book brought us a little more back into the spotlight. I feel like for the majority, most people don't know who we are. But we may have had an influence on a lot of people who went onto larger success in the New York music scene. I still think most people don't know who we are, aside from maybe music journalists.

Fleet Foxes, “Third of May” (2017)

That's definitely at the other end of my life. The Walkmen broke up and we had toured with Fleet Foxes and became friends with them. They were taking a break around the same time and [one-time Fleet Foxes drummer] Father John Misty had gone on to do his thing. I always thought they were the one band that I would absolutely love to play drums with. It didn't happen right away but eventually it started happening in a natural way. Robin [Pecknold] had sent me this song, it was the first one of his I played on and he sent me. It was just an incredible nine minutes of music so I went up to New York's to record with them. Initially I misunderstood and thought I was only supposed to play on this one small section on the song, but then I got there and realized he wanted me to play on the entire thing. It's such a cool track and was so memorable to play on. I know Robin's working on new music, [so I’m] kind of just waiting to hear what happens.

Muzz, “All Is Dead To Me” (2020)

We recorded most of Muzz at Isokon Studios, which is run by Dan Goodwin up in Woodstock and he co-produced the record. We recorded this song at my studio Silent Partner that I've started with some friends, including Paul, in Philly. We bought it as a shell and did all the renovation ourselves. A lot of that was happening while I was on tour so I'd come back and hang up with some drywall. It took a little over a year to build and opened about a little more than a year ago. It's been my dream for years before Muzz. I’ve been moving around horrible spaces my whole life. I think a lot of bands can relate, you're always playing at a place that has no heat or it's just in a garage somewhere and you're bothering all the neighbors. So it started as, "I need a space where I can work," but it definitely grew from there into a full blown studio and along the way, I picked up some partners here and there, people who wanted space to work in as well. It’s a place where I can record, collaborate with other people, produce music and produce records and just work.