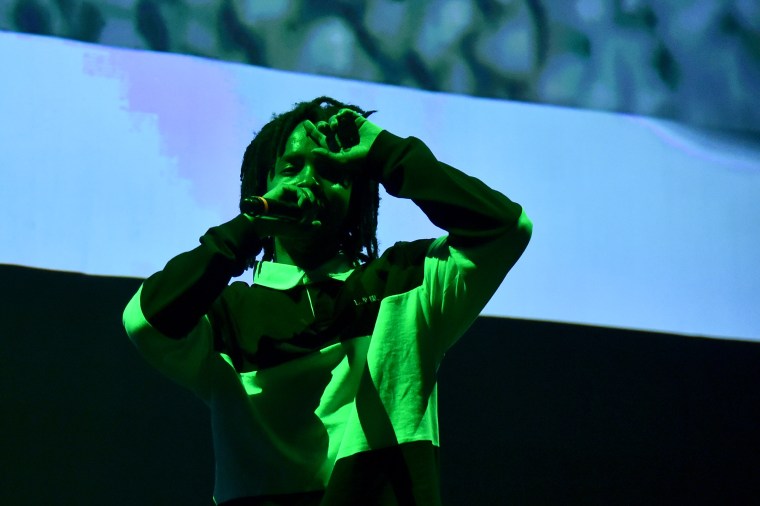

Theo Wargo/Getty Images

Theo Wargo/Getty Images

Toward the end of Some Rap Songs — the muddy, lofi meditation that Earl Sweatshirt released 11 months ago — he lays his parents’ voices over one another. There's audio of his mother, law professor Cheryl I. Harris, giving a keynote address at the symposium honoring “Whiteness As Property,” her groundbreaking article from a 1993 issue of the Harvard Law Review; she thanks her friends, colleagues, and son, and the speech, like the music underneath it, is hopeful. Harris’ voice is intercut with that of Earl’s father, the poet Keorapetse Kgositsile, reading his “Anguish Longer Than Sorrow.” That piece includes lines like: “For some children/ words like ‘Home’/ could not carry any possible meaning.” You imagine the competing vocals are supposed to cut against and complicate, but not cancel out one another. It seems cathartic.

Earl had completed this interlude — along with most of what would become Rap Songs — by the end of 2017, and meant to send the batch to his sometimes-estranged father as a sort of conciliatory gesture. But at the beginning of 2018, the elder Kgositsile died in South Africa, the country that made him poet laureate. Earl flew across the globe to make funeral arrangements, stayed abroad for nearly two months, then returned to Los Angeles to finish the album with a eulogy, recorded drunk and alone in a Mid-City duplex, that's really about the eulogizer. Whatever catharsis he was looking for is effectively drowned out.

Feet of Clay, an EP released without warning last night, is the first full body of work that Earl Sweatshirt has written and recorded since his father’s death. It feels, in many ways, of a piece with the album that preceded it –– the works share in common many patterns, cadences, and rhyming tics, which are occasionally the driving engines of their songs. But from the opening moment of Clay, there is a new (or rather: reclaimed) toothiness; compared to Rap Songs, Clay sounds like someone finally, desperately poking his head above water, grimacing at what he sees. Feet of Clay does not waste time looking for clean emotional arcs. Like all Earl’s work, but especially the I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside from 2015, it disguises itself as a depressive episode while documenting his efforts toward self-improvement and -introspection, rendering them as grimy, thankless processes that take place in cabs, bars, and sweltering kitchens.

That opening song, “74,” is the strongest in the collection, a burst of style and menace: “Your shit is not knockin’ like the Feds.” Since his debut mixtape Earl was discovered on Tumblr during the Odd Future explosion in 2010, Earl has been an obviously gifted, obviously obsessive technical rapper — a prodigy. What’s striking about his verses at the end of the decade are the way they have resisted disappearing inside themselves, or inside Earl’s formative influences.

This is a period in which the scenes in various cities have developed complex relationships with quote-unquote on-beat rapping: the way MCs from Detroit will slip in and out of the beat’s pocket, the way those in the Bay careen all across it, the way the new L.A. street rappers seem to race it. Earl’s patterns have grown more difficult and interesting, to where he sometimes raps with and against the drums in the space of a single verse. Sometimes he draws out words across bar breaks; other times he packs as many rhyming syllables into the front half of a line. This puts him in league with some of the underground auteurs working in New York right now, many of whom he frequently shouts out on Twitter, nearly all of whom are a decade older than he is.

“74,” like nearly every other track on Feet of Clay and Some Rap Songs, is over before the two-minute mark. That exaggerates the effect when Clay’s closer “4N” –– the longest song on either collection by more than two full minutes –– opens with ninety seconds of Mach-Hommy singing variations on the phrase “Send me the invoice.” Mach, the elusive, prolific rapper from Newark, is one of those mentioned auteurs, the records he sells for astronomical prices on his Bandcamp among the most evocative to come in the long tail of Roc Marciano’s watershed Marcberg.

The other guest on Clay is Mavi, the Charlotte native who, along with the New York-based rapper MIKE and the professional skateboarder Navy Blue, is a direct descendent-turned-collaborator of Earl’s. That itself is an interesting phenomenon: not only is Earl swiping and morphing the DNA of older rappers, but younger ones whose styles are based almost entirely on his. This would seem likely to create a self-defeating feedback loop, but it has in fact helped to clarify what makes Earl’s own writing unique from his followers.

Clay is largely self-produced, which underscores the EP’s already handmade feel. (It should be noted that the most entrancing beat is the sole contribution from Alchemist, who flips an Mtume sample into a song called “Mtomb.”) Earl writes around the varied emotions he’ll have following similar crises, sounding alternately like he wants to crawl out of his skin (from “OD”: “My memory really leaking blood, it's congealing, stuck”) or like he’s steeled for whatever (from “4N”: “We know death, aight let's go left.”) Since he came back from that Samoan boarding school for at-risk teens in 2012, it would seem that his project has been to make sense of his knotty, sometimes impossibly bleak inner life through a series of increasingly athletic exercises. With Feet of Clay, he shows that work toward those stylistic and philosophical ends does not have to lean on artificially sunny frameworks.