In her 1995 essay, “Literature and Public Life,” Toni Morrison examined how pop culture affects our relationship to other people. In it, she says, “We live in the age of spectacle...spectacle that promises to be safe, clean and cheap, but turned out to be dangerous, dirty, and expensive.”

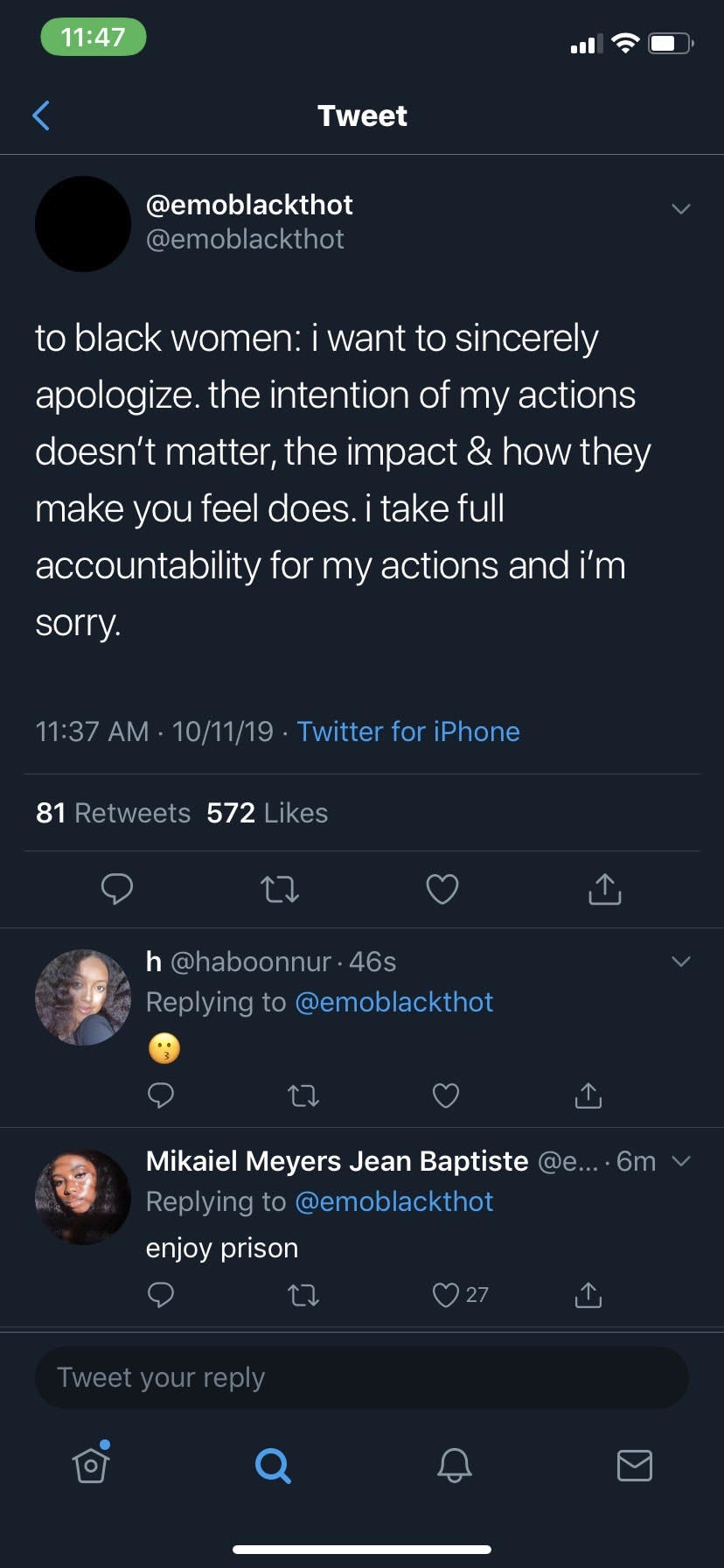

24 years later, that assessment holds true in a number of instances on social media. One of the most recent — and disturbing — examples is the fallout of EmoBblackThot, who, up until last week, convinced 170k followers they were a queer dark skinned Black woman who advocated for self-care. But in a PAPER Magazine feature that dropped on October 11th, hundreds of thousands of people online learned that the identity of their favorite account was instead a cis, lightskin man named Isaiah Hickland. The reveal was a perfect storm of identity, online manipulation, and deception.

Hickland carefully selected a caricature of what they deemed Black women to be, but in a more palatable sense. They were a digital maternal figure, providing online refuge for those in need and reminding everyone to take their meds (birth control included), drink water, straighten their necks, and practice self-love. The harassment Black women face online was expertly evaded by procuring this unrealistic image on social media that is positive and uplifting to their Black and non-black followers alike. EBT never took anyone to ask — outside of the occasional #BLM-related tweet — and in that sense, they never experienced the digital life of most Black women.

In Lauren M. Jackson's 2014 essay, “Memes and Misognynoir” she wrote about digital blackface, saying, "These attempts, while hilariously transparent, take advantage of the relative anonymity of the internet to perpetuate decontextualized stereotypes and project an image of Black people that fits the desire of anti-black individuals." In Jackson’s 2016 essay for Teen Vogue she expands on the epidemic, writing “Our culture often associates black people with excessive behaviors, regardless of the behavior at hand. Black women will often be accused of yelling when we haven’t so much as raised our voice.” The omnipresent, unavoidable, white and male gaze that imposes limitations on Black womanhood through stereotypes is heightened through social media. Everyone has unbridled access to Black women’s ideas, thoughts and our intra-community conversations, our public feeds are mined then mimicked. So when EmoBlackThot revealed their identity for Paper last week, what was more jarring than who they actually were, a bisexual cis Black man, was who they decided to be.

Isaiah Hickland could've been anyone they wanted to be but decided to carefully study and mimic the voice of a Black woman. This election gave them the digital authority of Black women without any of the consequences –– they weren't the face, but the voice at the intersection of stan Twitter, Black Twitter and what is referred to as cherry emoji or 'hoe' Twitter. Sex positive, darkskin, woman and queer, contesting them with no face or politic outside of the occasional #BLM post was impossible. The EBT account propelled to notoriety for its unthreatening rallying calls to love your hair. Demanding the mainstream to represent Black women fortified their credibility and made them charming and likeable.

Regardless of the vitriol, Hickland is being given a type of grace that would never be given to Black women. He has not been exempt from criticism and harassment as a result of the unveiling, but for those of us who face harassment and have seen how Black women are picked apart and disciplined publicly, this pales in comparison. While we don’t want this harassment to continue, we see the grace and space that is given to those who hold these privileges. If anything this situation shows us is that being visible is dangerous and only protects certain folks from accountability. Black women are punished and discarded.

Below, as Black women who have all been harassed publicly and have an intimate relationship to hyper-visibility that is rooted in the surveillance of digital life, we discuss the ramifications of EmoBlackThot's cosplay, Black women’s social capital, and how media profits from Black rage.

What does it mean to see the use of Black women’s perceived social capital and voice used as cosplay for so many people that are not Black women? Visibility has hurt Black women more than it helps us, which is the opposite for everyone else. How can we protect our intellectual labor and likeness?

Wanna: Blackfishing and digital Blackface have allowed non-black people access into communities that they have no business frequenting. We’ve seen this being played out on the now-defunct app, Vine, and the emergence of the popular app TikTok, in which our likeness is being mimicked in an attempt to gain social capital, yet actual Black women are ignored and overlooked when it’s time to celebrate our countless contributions created in this digital space. So how can we protect our intellectual labor when other people feel like they’re entitled to it? How do we put a stop to the blatant theft and erasure that has a history of rewarding everyone but us? With every tweet and article outlining the gravity of this situation, Black women have been met with resistance and ridicule, whilst non-black people have been able to profit from our labor. Do I wish to live in a world where Black women are able to eat off our cultural production? Yes. But I’m not hopeful that this will happen, especially when Black women are intentionally shut out.

Najma: I personally believe that people think Black women are taking something away from them by using their platforms. Society as a whole is used to speaking at us, everyone is busy explaining us to us, but with social media we have some agency to tell our own stories. But only to a certain extent. Black women's hyper-visibility is the umbilical cord of the internet, it exists to nurture and feed everyone but us. First and foremost, I think acknowledging that this is a form of power is important. Knowing our cultural impact helps us understand ourselves outside the lens of victimhood. Unfortunately, I don't believe that we'll ever be able to protect our intellectual labor and likeness, I think the best thing we can do is continue to transform and create and allow ourselves to be our whole, authentic selves. To be Black is to be hyper-visible, we can't control that. I wouldn't advise anyone to stop posting online or to silence themselves about certain things because I believe in the importance of digital communities we foster but I would suggest practicing even more discernment and collaborating with other Black women online on your own projects. Create that zine, make that podcast, make that YouTube channel. Document yourselves and thoughts outside of Twitter and Instagram.

Clarissa: Visibility and notoriety for Black women in this digital age means putting your safety on the line. For many of us who have been publically targeted it has altered our lives in ways that we are still contending with. Seeing someone like Isaiah use our voice and capital to manipulate hundreds of thousands of people online to think they’re a Black woman isn’t shocking but it is a telltale sign that this world is not prepared to actually show up for Black women. Isaiah wouldn’t have gotten away with this if he hadn’t seen how Black women’s likeness is stolen and used in digital media across the board. I think it’s the work of those in privileged positions to address the exploitation that keeps Black women marginalized. How are publications, music brands, and advertising agencies all profiting from the “likeness” of Black women’s digital labor? What are they doing to address that? The answer to that is nothing most times because it requires people giving up positions of power and addressing the harm they’ve caused in real ways.

What does a figure like EBT mean for how we consume Black women’s social capital? Do you think this moment will shift this? Will people actually invest in Black Women’s voices or just say it to be in the dominant conversation?

Wanna: EmoBlackThot was more than an account, it was a community. The persona provided comfort and familiarity to the audience it successfully infiltrated. This was in equal parts, strategic and conniving. Black women’s identities have been the subject of belittlement and torment online, from which groups and organizations have tried to restore in the wake of “Black Girl Magic” and similar movements that emphasized the importance of self-love and confidence. It is no coincidence that the account emerged during a time where Black women were loving on themselves proudly, whether that be through the natural hair or melanin movement. EBT preyed on a group of people who wanted to belong and feel ‘included’ in the powerful dynamics that is Black sisterhood, womanhood and community. It is the hope that people will invest in Black women and our work but I don’t believe this will happen until we are respected and valued. Investing is more than a byline, investing is putting Black women in prominent positions that aim to inform and amplify our voices and creating an opportunity for more growth.

Najma: EBT's presence online is everything people want Black women to be: non-threatening, nurturing, and empowering. The community EBT built couldn't exist without those aspects. This moment is proof of the cyclical cultural paralysis we exist in. People only care to listen to us when it benefits them. With #yourslipisshowing, Black women noticed how trolls masqueraded as Black women before the 2016 election, this was before any popularized discussion about digital blackface and it wasn't until it was too late that anyone paid attention. The outrage will get people talking about a phenomenon that has existed before the internet. People have always emulated and appropriated the likeness of Black women. I don't bank on anyone to change this for us. We're dehumanized further by being hyper-visible online. Accountability can only work when both parties see each other eye-to-eye, when everyone recognizes each other as human and deserving of safety and respect.

Clarissa: In order to move these conversations we have to look to Black women scholars who have written on this in the past. Nothing is new under the sun and even on our worst days we can find answers to the toughest questions in the past.

In bell hooks’ 1992 essay “Eating The Other: Desire and Resistance” she speaks to why nothing that becomes a commodity can keep its original core values. “Communities of resistance are replaced by communities of consumption (Consumption being a social relationship...one that makes it harder and harder for people to hold together, to create community.)” EBT represented a community that was untouched and, more importantly, was a figure that people felt safe with, a figure that was always giving and comforting. Isaiah forgot that Black women and his account by proxy are not allowed to be wrong or fail. This moment was a deep look at how investing in Black women’s voices involves a cultural shift to seeing Black women as more than just archetypes or hashtags but as pivotal cultural workers that deserve humanity but are living in a world that refuses to grapple with that.

In regards to the aftermath of EBT’s reveal, how do you feel about the utilization of Black women’s rage/anger as a sort of media currency when it comes to controversy as a whole?

Wanna: In an age where outrage is often celebrated or demonized depending on the target, Black women are used as mouthpieces to spearhead and dissect several conversations on social media. People look to us to boost the conversation at hand, without considering the consequences, specifically harassment that comes with being outspoken on social media. To be a visible Black women on social media is to be treated like a spectacle with an audience eagerly watching the performance. Our anger is supported when it falls in line with pressing issues that the masses deem worthy, but we are quickly abandoned and alienated when the majority decides that we are being too loud or too aggressive. To take it one step further, the language used to detail our work is likened to gossip blogs and is often coded in anti-Blackness. Perhaps this is why sound, critical analysis by Black women is immediately reduced to “call-outs” or “putting somebody on blast” and never labeled as a well-respected critique that everyone else but Black women are afforded.

Najma: The public is obsessed with displays of outrage from Black women and this outrage is rewarded with bylines and retweets and followers. Black women's self-exposure and rage is a form of currency for publications that rely on their crop of underpaid token diversity freelancers. Trauma porn has launched careers, the hyper consumption of the violence Black people face is an epidemic but it also gets clicks. It hasn't moved the needle on the issues we face, our realities stay the same. Everyone indulges, pats themselves on the back for being "aware" and “woke”. It's all performative. The show goes on.

Clarissa: Black women in the digital space have been the moral compass for the ways that dominant culture should be. In that way, it makes Black women vulnerable. We assuage the public’s culpability in how media, controversy, and public spectacle are supposed to be dealt with. Many times our rage and the cyclical nature of apps like Twitter only allow for surface level engagement. These patterns lead to the same conversations hitting the timeline every month, ones that are just about pointing fingers at the same systems. Our rage is often recycled for clicks. In this way, for those of us who have been harassed, we have to disengage, make strict boundaries about our profiles, and be the ones spearheading conversations because we know how quickly we can be eaten alive.