Kindness’ beautiful and glorious return

A revealing chat with the British soul artist about their collaborative new record, their formative relationship with the late Philippe Zdar, and more.

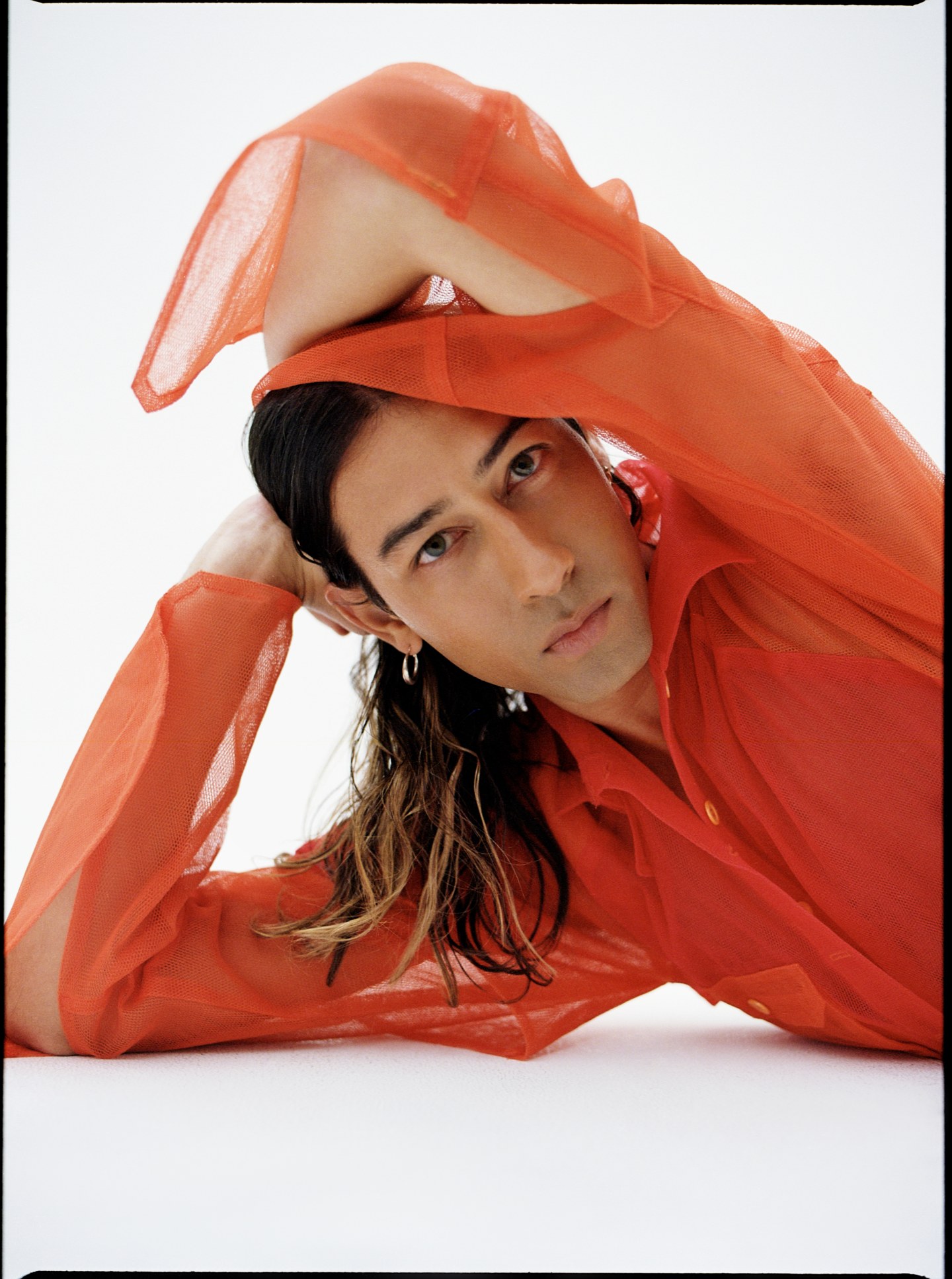

Michele Yong

Michele Yong

In the fall of 2011, I was in hot pursuit. I wanted to interview Kindness for my FADER column about rising British artists, Dollars to Pounds, and it took four months and 49 emails to pin them down. At the time Kindness had released just two singles: 2009’s Replacements cover “Swingin’ Party,” and his buzzed about 7-inch “Cyan” three years later, but no one knew Adam Bainbridge; There were no interviews, just a record sleeve bearing a beautiful face with that enviable jawline.

For that first meeting, and for their GEN F not long after, I spent many hours drinking tea with Bainbridge as we covered the bio basics: growing up in Peterborough, England with an Indian Mom and English dad, their winding path to music, their months-long quest to snare the feted French producer (and one half of Cassius),Philippe Zdar.

When we Skype this past August — barely two months since Zdar’s tragic death — Bainbridge is at home in East London, fresh from a trip to Paris where they spent time with the producer’s family and friends. Theirs was a formative partnership forged in the studio, that grew to become a deep friendship. Together, they produced Kindness’ debut LP, 2012’s World, You Need a Change of Mind, re-teaming once more at the tail end of 2018 for their third record, Something Like a War.

“Our relationship was respectful, but it was also argumentative and I liked that,” they recall, smiling. “A week after I left the studio I was like, ‘Why are you being so angry, why are you telling me what to do?’ And he was going, ‘You think I don’t know about mixing a record! I know about mixing a record!’ We were arguing about sequencing! [Laughs] But it’s good to have that seriousness and that passion and belief in what you do.”

Something Like a War is a beautiful record and a glorious return after a five-year pause. When the album cycle for Otherness concluded in 2015, Bainbridge was exhausted, and relocated to New York in 2016 to spend a year “just living life.” They zipped around on Citi bikes, DJed, and swam daily in a public pool bordered by a 170-foot Keith Haring mural. One year stretched to three. During this period Bainbridge made music with Dev Hynes, Solange, and Robyn and, in the catharsis of working with others, found their way back to Kindness to birth Something Like a War, their most joyful, optimistic collection yet. Their funked up mélange of R&B and soft-centered pop orients around lounge-y grooves and seductive bass lines, where brass and strings complete each song with the perfect flourish.

The power of acceptance; the transformative way love opens you up, and the strength in vulnerability, are just some themes that come flooding forward on first listen. (Meanwhile, the title’s pulled from Deepa Dhanraj’s 2003 documentary about the Indian government’s forced sterilization of women in the '70s.) “Those themes seemed appropriate for the music that was being made and for the time I was spending in New York,” they explain. “Other than what was happening in politics, things felt optimistic and rooted in community and solidarity and proactive generosity towards each other.”

That generosity extends to the record’s sprawling roll call of collaborators including Jasmine Sullivan, Sampha, Kelela, fellow Brit Cosima, and Swedish songbirds Seinabo Sey, Nadia Nair, to name a few. And, of course, there’s Robyn, who sings on two tracks and co-writes four, including “The Warning,” the LP’s beating heart and the first song the pair worked on together back in 2013.

I’m curious about how your partnership with Robyn works.

Funnily enough it relates to not putting so much pressure on what we do. Things would happen when they were meant to happen and a song would develop over years. There were things that I maybe wish we’d finished sooner, but we were both going through it: We both had break ups at a similar time and there was a moment where working on music was the farthest thing from our minds. We were just spending time together — going for walks and chatting and being part of each other’s support network.

I’ve come to realize this through losing Phillipe recently, when working with really special people, the work is the secondary element. If I’m making music for me as an artist, the real satisfaction comes from making it, it doesn’t matter what the end result is. Me and Robyn have a bunch of really great songs that are like ongoing projects, whether there’ll ever be the right place to release them is another thing.

Were you able to go to Philippe’s funeral to say goodbye?

Yeah. I went back. It’s been very touching to be so involved in a lot of the close family and friends arrangements, people continually talking online and on WhatsApp. There’s a big community, hundreds of us at his funeral, all connected by this one person. A lot of us knew each other already it was just Philippe was the final bridge. I didn’t know Cat Power before personally, but it’s quite funny to chat with Chan on Instagram now.

He brought everyone together.

Yeah and will continue to I’m sure. It might be wishful thinking but I know a lot of us expressed an interest in working together if only to tell some good stories and reminisce, and maybe congregate in the studio and see what magic might come of it. Especially with this feeling that someone who had so much energy in life, continues to have a very present musical energy everywhere still.

I wanted to talk about your Red Bull lecture. It felt like you were itching to get things off your chest, especially when talking about your sexuality, and the hard costs and emotional costs of making music these days. You got so personal.

To be completely honest, I was somewhat surprised that I was being asked that early in my career. I wanted to connect through honesty and also share something useful. And maybe, as much as it’s a torrent, and it’s probably both hard to watch and hard to follow at times, the difference with a conversation like that is it’s not going to be edited down, it’s just who you are. It also came at the end of what was fundamentally an album campaign, where I hadn’t got to the crux of what I was trying to say in any other interview.

Because you weren’t being asking the right questions, or it wasn’t the right time?

A little bit of both. I was also in a relationship that wasn’t conducive to being myself for some of that interview period. I was sitting on a number of things because it was just going to cause more drama in my own personal life. Getting out of [the relationship] meant I could speak very openly about everything — for the first time in my career to be honest. Also, people are reluctant to go to very heavy places in interviews, and short of extremely long features or articles written over multiple interviews, there’s not going to be the opportunity to. So I kind of understand that. When a journalist’s approach to music is music above everything, then very often it’d about collaborators, the studio, and process. To me, that’s the least interesting thing about anyone that makes something and why they do that.

Whose opinion do you trust the most when you’re in a bind, emotionally and creatively?

I’d say my partner Phoebe [Collings-James]. Robyn and Dev. Now I understand that I have confidence in what I do and enough confidence whatever opinion I ask, even if it comes back with a powerful suggestion of change, I can take it and probably make something better because of that. Robyn can say to me, that chorus isn’t a chorus, and rather than being in my feelings about it, I’ll just be like, Yeah! LET’S DO IT! Hope you don’t have anything to do because now we’re doing this together right now! And that’s incredibly helpful.

It’s wild how long you’ve known Dev and how many musical iterations you’ve seen each other through.

We’re both relatively small-town kids from England who came up touring while his bands were playing these raucous post-screamo punk shows. Being in the tour van and playing nonsense rap and Audioslave covers in Sunderland, that footage must exist somewhere! Now he’s writing with Mariah Carey and doing prank videos with her on Instagram! What is actually happening!? It takes an enormous universal musicality to pivot that hard and make it stick, but I’d like to think we’ve both done fairly well in our pivots.

How do you feel about Something Like a War now?

I feel proud and happy to have made something very personal. That was what was interesting about the mixing process with Philippe: I felt a certain amount of pride and satisfaction that I was bringing a finished album to the studio. To go from being this completely raw, naive artist that had never made a record before when I worked with Philippe the first time, to now on my third record, having made significant works with other people as well, it was nice to come to Paris and say, Look what I’ve done, look what I’ve brought you, it was all in my head and now it’s on this hard drive. It’s growth, but also a necessary amount of self-confidence. There was something really wonderful about that.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

It’s not a wonderfully optimistic time for global politics and society, but if I were to imagine things were to get better, I’d like to be making music in a way that’s enjoyable and sustainable. It would be nice to think that at least for the three or four generations of working musicians now, there’s a future that doesn’t rely on constant, vigilant monetization of what we do. It’s exhausting and counter-productive, but it’s kind of what scarcity and capitalism has forced on us in some ways: we always have to be working and you’re only as good as your last record. Music is a somewhat selfish career and music itself foists selfishness on the artist because it’s all consuming. It would be good to have space for loved ones, and for them to not have to exist in the framework of what I do. I think about it a lot. If it becomes unsustainable I’ll quit the whole thing and open a breakfast place doing Indian food in East London. There’s lots of Indian restaurants but not that many that specialize in breakfast. Indian breakfasts are a class act!