SPIDER jacket and pants, 3.PARADIS sweater.

SPIDER jacket and pants, 3.PARADIS sweater.

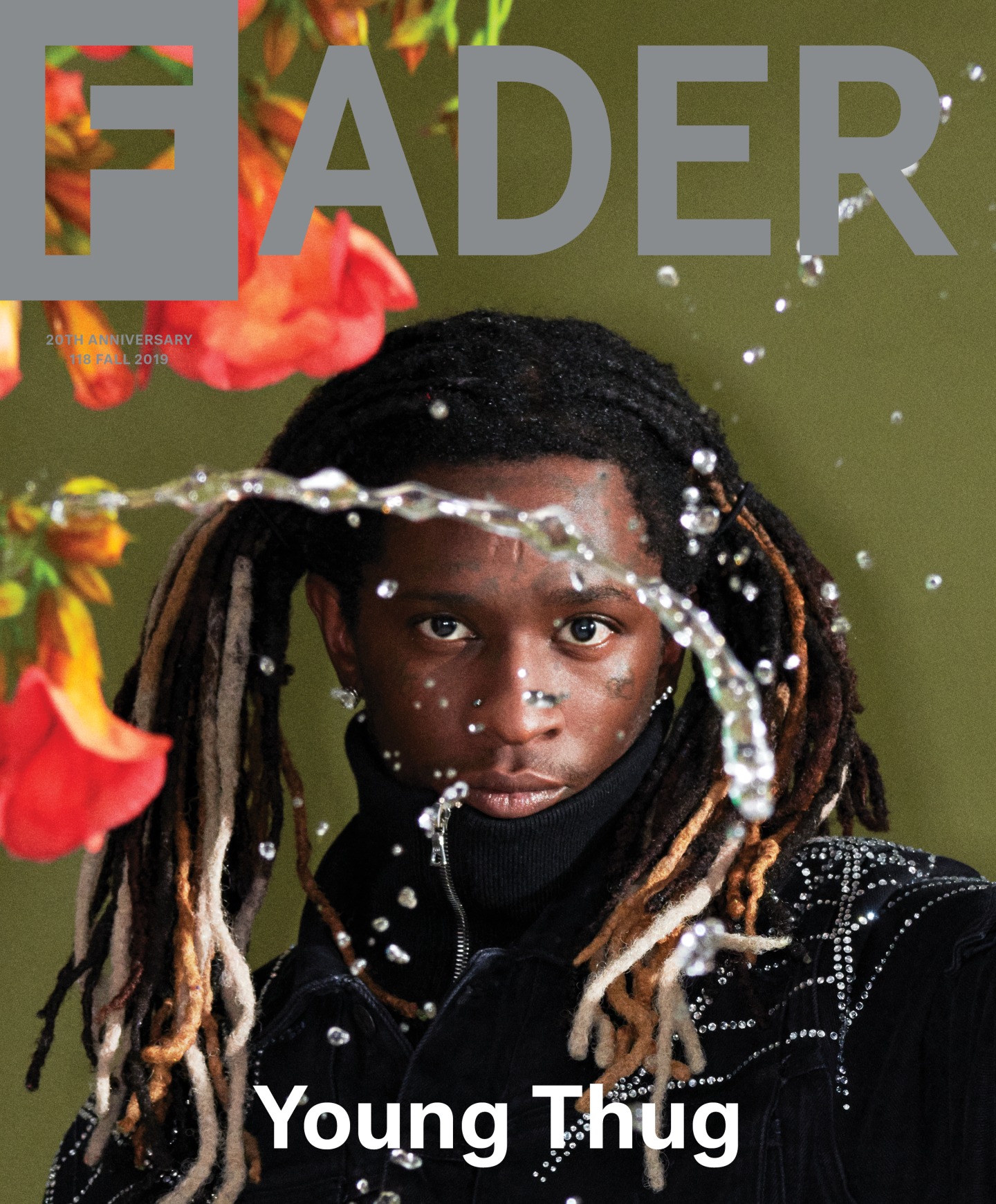

Buy a copy of The FADER's 20th Anniversary issue featuring Young Thug, and order a poster of his cover here. As part of The FADER's 20th anniversary issue, we teamed up with Vinyl Me, Please and Goose Island Beer Company to offer a special artist compilation vinyl bundle featuring some of our favorite artist track releases from the year. Pre-order is available now exclusively at Vinyl Me, Please's shop.

Young Thug strides past me and, almost to himself, starts singing a line from “Because I Got High,” the novelty weed hit by Afroman. “I was gonna pay my child support, but then I got high…” We’re backstage with Thug’s dozen-plus entourage at the Belgian music festival Tomorrowland, and the Atlanta rapper’s voice dances off the cramped walls even without Auto-Tune.

Far outside, EDM DJs play across several different stages on a crisp Saturday evening. Their basslines bleed ominously through the walls of our quarters, along with an occasional roar of a crowd. Thug will perform in about an hour’s time: his Afroman, delivered like a cheeky seventh grader showing off for mom, lightens the room.

Tomorrowland resembles a Harry Potter theme park designed by street performers — the fire-eating, Cirque du Soleil kind. Hundreds of thousands of people will gather over two weekends in sprawling recreation grounds in the sleepy town of Boom, just outside of Brussels. These fans will get baptized in a life-affirming cocktail of neon lights, mud, and (mostly) electronic music, played in front of towering backdrops designed like steampunk palaces. The festival’s theme is “The Book of Wisdom,” and Young Thug’s chapter stands out in its pages.

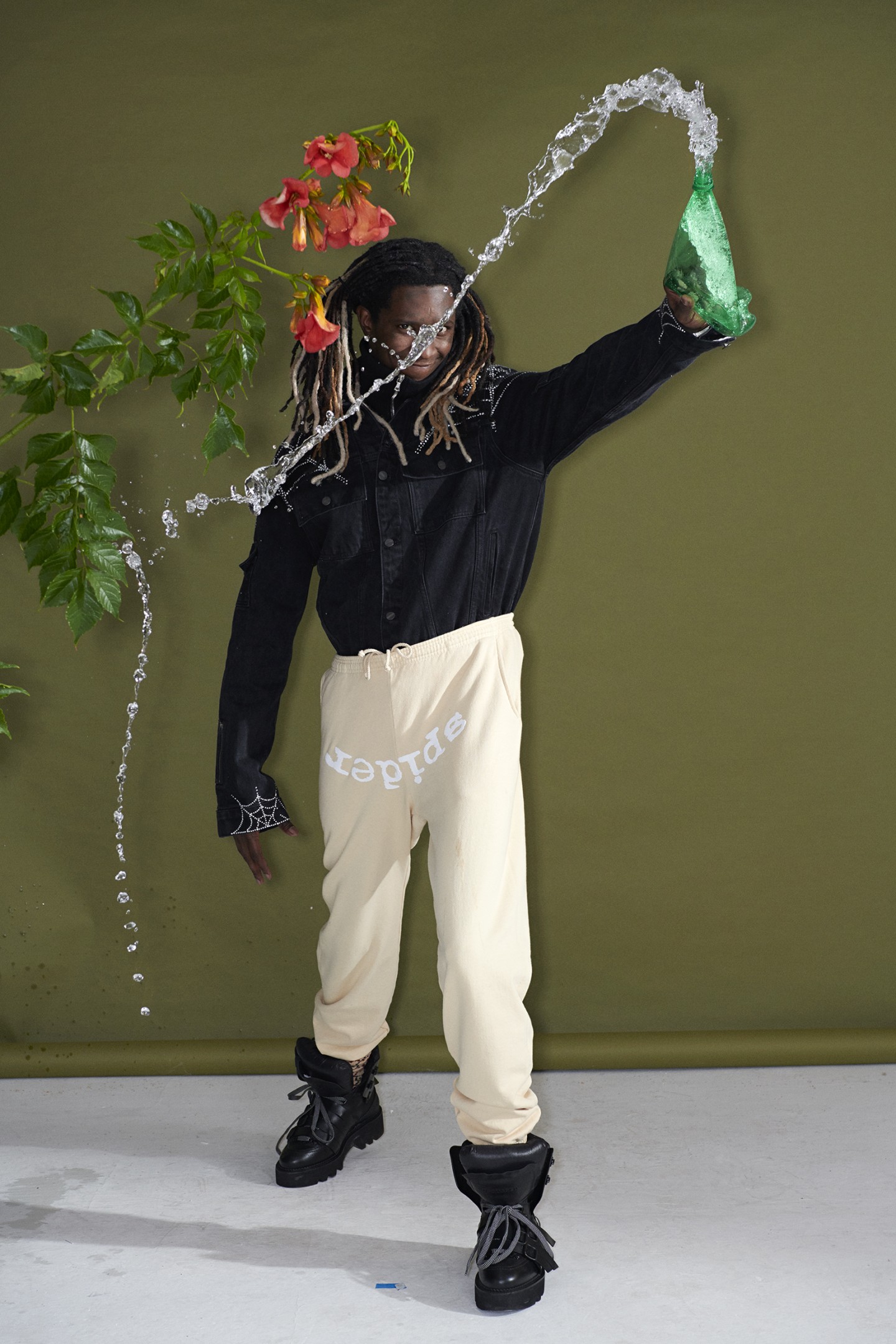

SPIDER jacket and pants, 3.PARADIS sweater, YOUNG THUG'S OWN t-shirt, DSQUARED2 boots.

SPIDER jacket and pants, 3.PARADIS sweater, YOUNG THUG'S OWN t-shirt, DSQUARED2 boots.

Thug’s set at Tomorrowland is unexpected but not undeserved. When an Uber driver in Belgium asks me who I am interviewing, the language barrier leads me to use a lot of superlatives. But they’re also true: Thug is a 28-year-old hitmaker, visionary, fashionista, one of the most polarizing artists of the 21st century, androgynous icon, and leader. His birth name is Jeffery Lamar Williams, and he keeps changing the world.

EDM purists don’t care about hip-hop pedigree, though, and as I hover in Thug’s green room, I’m uncertain how his crowd will react. For now, the mood backstage among Thug’s team is sedate. The party may have left with a group of girls who tagged along and got rejected at the gate by Tomorrowland security; no wristbands. Strick, an artist and incorrigible flirt signed to Thug’s record label YSL Records, resigns himself to the minifridge. People begin to break off into their own conversations, some of us sit on the black leather couches, others on the fake grass carpet.

Thug’s performance comes at the end of a run of European festival dates. He’s in the country for less than 24 hours, and I’m with him for six. Thug is in superstar mode for most of the time — a reluctant cog in the machine he’s built for himself — but when we eventually talk, he peeks from behind the extravagant veneer.

“[People] misunderstand my mind and my heart,” he says, steely yet receptive to my questions. “Because of what they see, not what they know.”

For about an hour, Young Thug tells me what he knows.

Young Thug’s near-decade-long career in rap music has been unprecedented. He reshaped hip-hop’s sound and image again and again before releasing a “debut album.” He has feuded with his biggest influence (Lil Wayne) and collaborated with rappers he has inspired while retaining his distinction (Travis Scott, Playboi Carti, Juice WRLD, and many, many more). He shared a 2019 Song of the Year Grammy for his work on Childish Gambino’s “This Is America,” yet there’s an overwhelming sense that his moment still has yet to arrive. A recent string of underrated releases (2017’s Beautiful Thugger Girls, 2018’s Slime Language, and “High,” a song featuring a rapturous sample of Elton John’s “Rocket Man”) meant Thug was left treading water for the first time in his ascendant career.

Around February 2019, Thug started assembling ideas for his album So Much Fun. He flashes a smile that could clean a comet: “I really didn’t think too much about it,” he says. “It’s just fun music. You only should play this music when you’re having a good time.” His new song “The London” with J. Cole and Travis Scott is a prime slice of palatial aspiration rap, and is already Thug’s highest-charting single of his career.

The song’s success is vindication for Thug after spending much of the last 12 months on other endeavors, including his fashion line SPIDER and music imprint YSL Records. “I relaxed, worked on my label, got everything how I needed it,” he says, scratching the two diamond studs embedded in his bottom lip. “[I] forgot about myself, felt like a lot of people forgot about me.” He quickly edits himself: “Well, not forgot. But I was making big moves.”

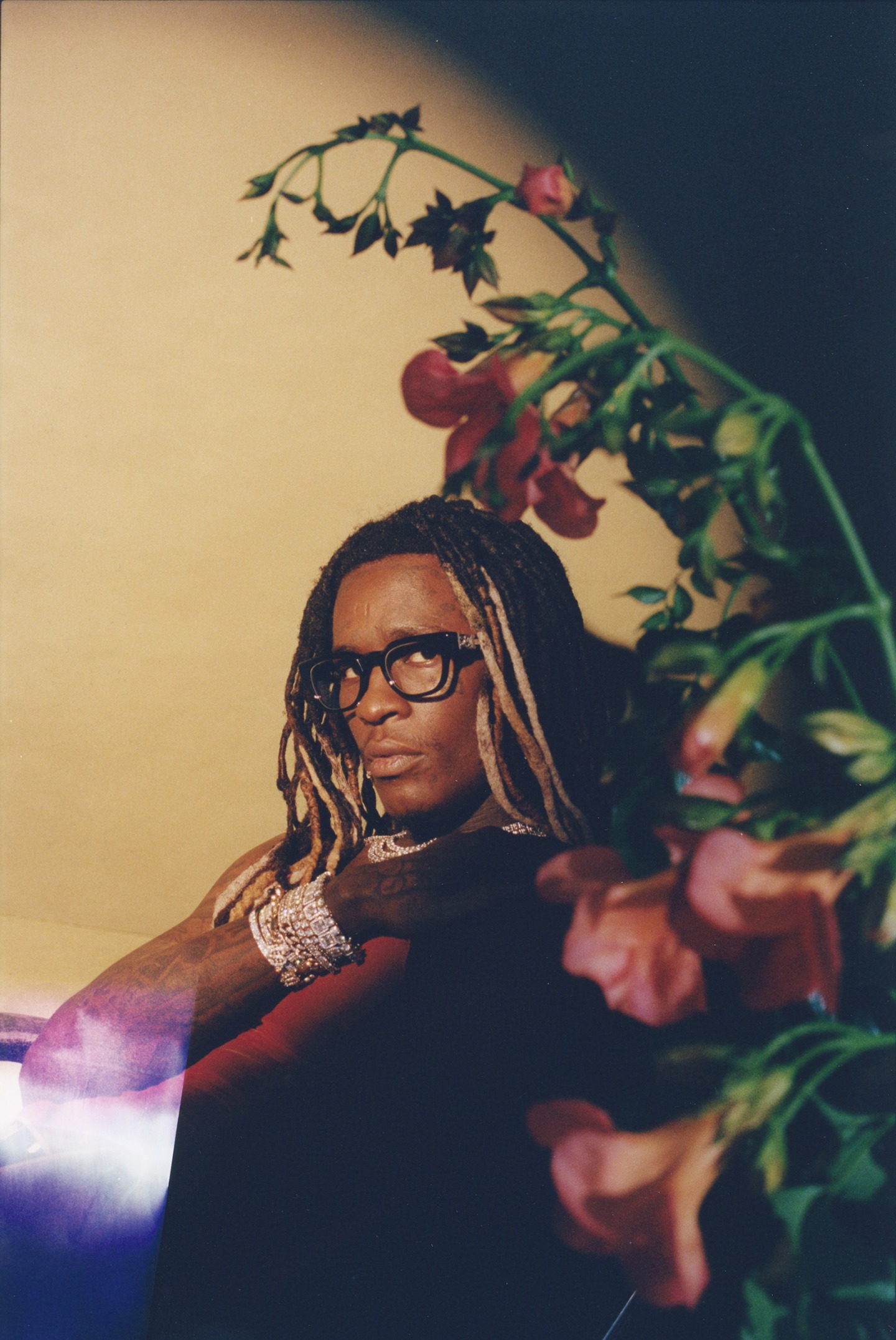

MOWALOLA jacket, shirt, pants and shoes, YOUNG THUG'S OWN glasses and jewelry.

MOWALOLA jacket, shirt, pants and shoes, YOUNG THUG'S OWN glasses and jewelry.

Three hours before his festival performance, I watch Thug from the lobby as he enters the Hotel Sofitel Brussels Europe, his ritzy home base during his brief stay in Belgium. Thug is barely visible from across the hall, flanked by his entourage and shielded by the hood of a two-toned varsity jacket. He escapes to an elevator and rests his head wearily on the wall inside before the doors close.

Some of Thug’s crew remain downstairs: There’s Be EL Be, the video director who is the Hype Williams to Thug’s Missy Elliot, and has known Thug since the rapper was 19. The guy in the tie-dyed Travis Scott hoodie is Cash, who recently received a degree in health science but is now “a whole ass tour DJ.” Be EL Be remembers how Thug once threw a water bottle at one of his old DJs during a show — his crime was playing one of Thug’s tracks with a DJ tag. “He is very precise,” Cash laughs.

At around 8 p.m., three Sprinter vans arrive to drive roughly 18 of us outside of Brussels to Tomorrowland. Amidst the stress and tussle of loading everyone into the vans, I’m formally introduced to Young Thug for the first time. His entire outfit save his shoes is DSquared2, a combo of boarding school prep academy and Hot Topic. He has an enormous diamond stud in one ear, a glittering string of stones in the other, and nine diamond charm bracelets on his wrist. His braids are different shades of brown, black, and white, like Rocky Road ice cream. He smells amazing.

As I shake Thug’s hand, he looks at me with the low eyes of a duke regarding a subject who messed up a royal greeting. I try not to take it personally.

Thug is royalty, in a way. His brood includes six biological children and countless rappers. Thug is credited as one of the foundational figures of “mumble rap” before it had a name, but both fans and detractors overstate how unintelligibility defines his work. Tonally, he is the son of a Looney Tunes voice artist and Wyclef Jean with a Southern drawl; he has swum carefree in this range throughout his catalogue, never sounding like a joke where others would. Listing off the best rap projects of the century requires several dips into Thug’s catalogue, and each transmission is tuneful down to their project names: Barter 6, Rich Gang: Tha Tour Pt. 1, 1017 Thug, Slime Season 2, Beautiful Thugger Girls.

It may require a few listens, but Thug’s images will stick. They can reveal themselves as writerly (“If I leave a nigga white T-shirt red, it’ll be a peppermint or a baseball, nigga,” on “Mine”) and ethereal (“Nigga have you ever dreamed? I was the man and you a thing” on “Amazing”). There is potent loyalty to his family on “OD,” and his cartoons-and-cereal horniness shines on lines like, “I’m so geeked up I might fuck a condom” (“Thief In The Night”) and “Booty fat like she eat asses” (“Calling Your Name”). Then, there’s Thug’s braggadocio, snappy, dynamic, and unequivocal — hedonistic pearls like “My weed is loud and you smokin’ libraries” (“Ridin”) are scattered across all of his songs. Thug’s lyrics can yield destinations unique to each listener, but the journey is never not entrancing.

Even when he’s difficult to understand, Thug takes the listener — and hip-hop by extension — to new and exciting places. Thug likes to refer to himself as an alien, but he’s really a human who can access more dimensions: each time he caps a line with “you diiiiiiig?,” twisting the word like taffy, it’s an invitation and challenge to find your own way in his world.

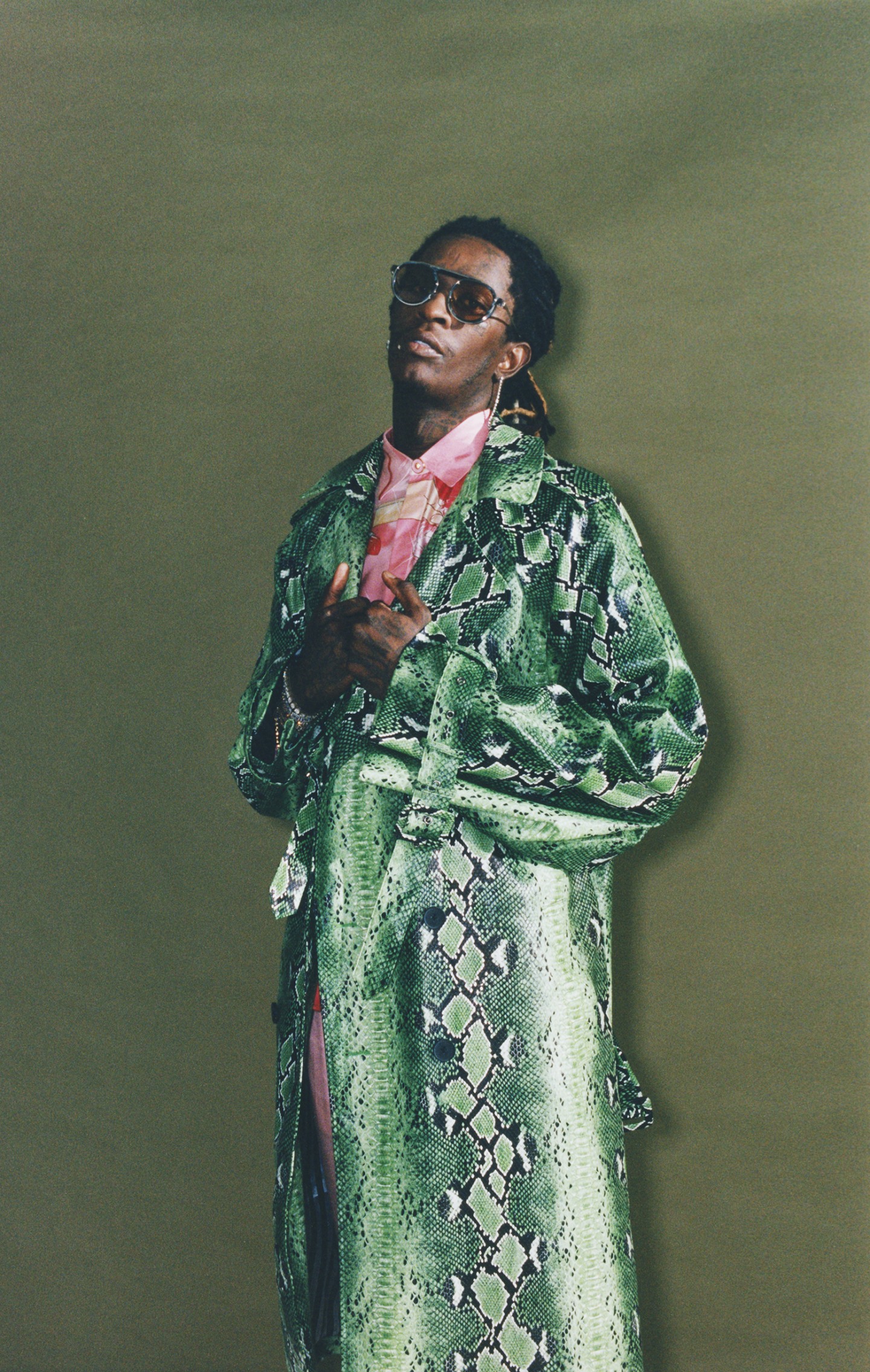

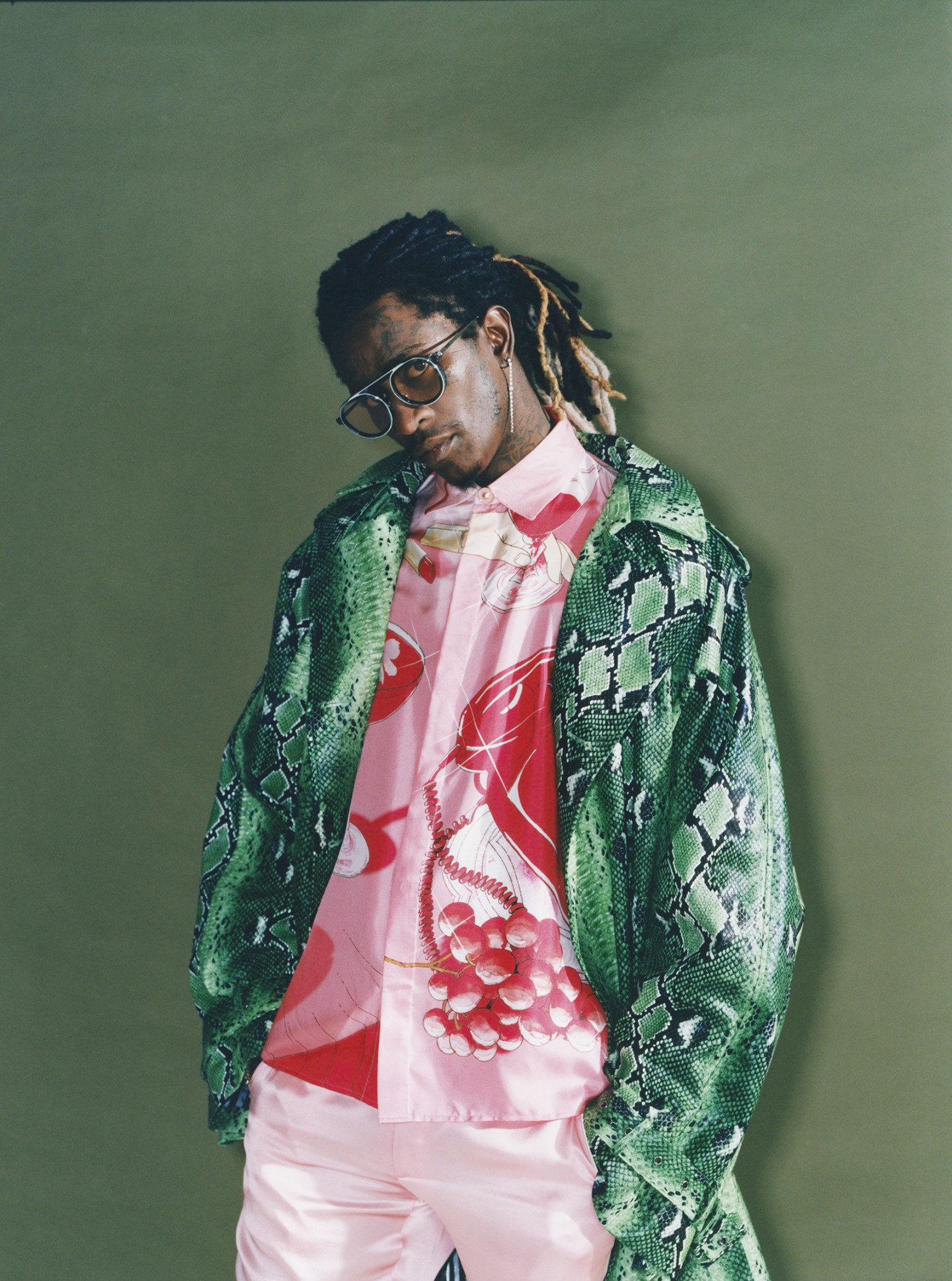

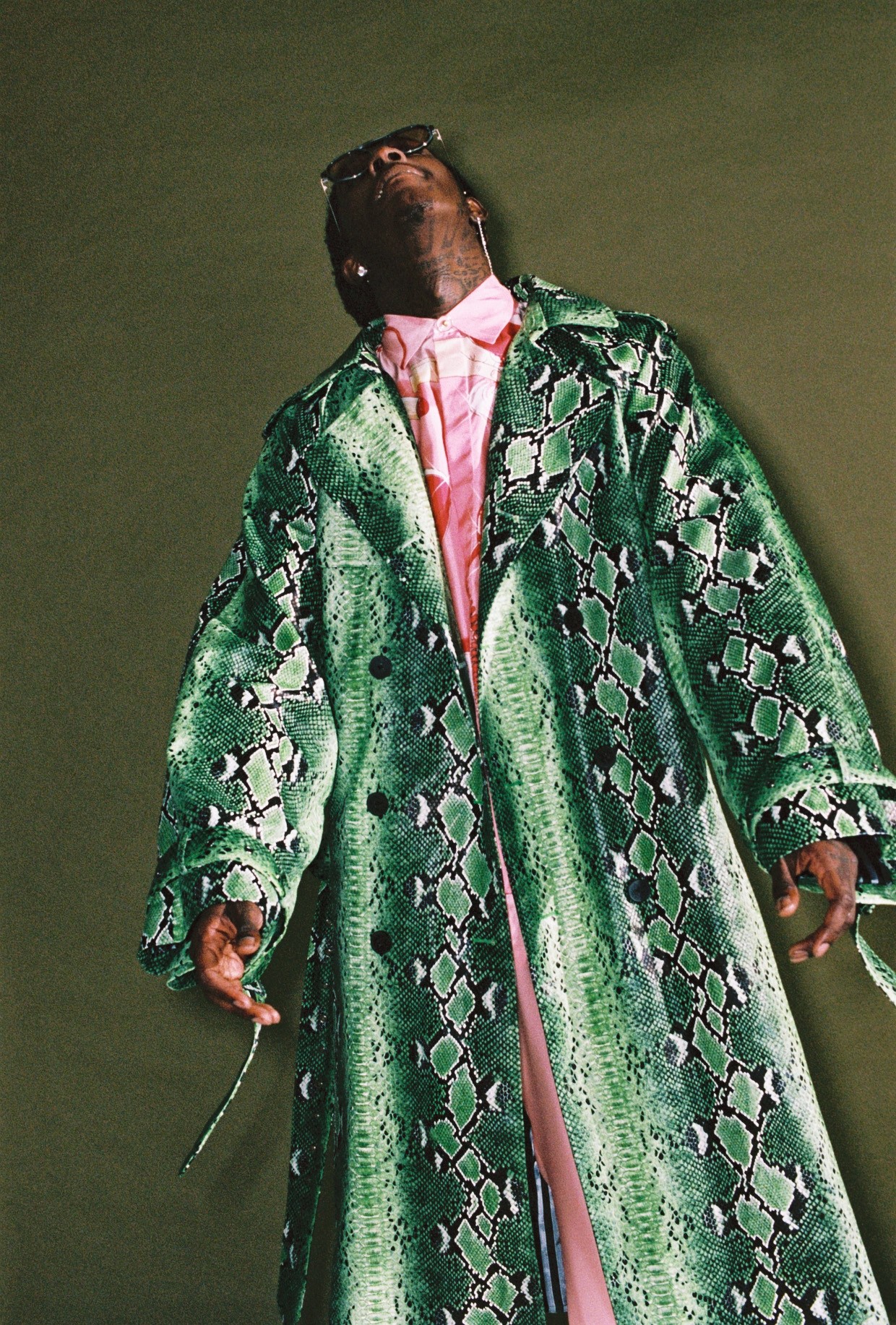

DAILY PAPER coat, CASABLANCA shirt and pants, VERSACE sneakers, THIERRY LASRY sunglasses.

DAILY PAPER coat, CASABLANCA shirt and pants, VERSACE sneakers, THIERRY LASRY sunglasses.

A five-star hotel in Brussels seems further from where it all began for Thug than any unit of distance can adequately measure. Jeffery Williams was one of his family’s 11 kids, born in Atlanta’s Jonesboro South project housing razed in 2008 by the local government. From his first mixtape I Came From Nothing to So Much Fun, Jonesboro is Thug’s foundation. “It affects [my music] a lot because it’s being truthful,” Thug tells me. “[If] you’re a truthful artist, you going to write about what you went through. I went through a lot.”

Peewee Longway, the jolly and renowned Atlanta rapper with a dazzling gold tooth grin, met Thug — then just Jeffery — when they were kids in Jonesboro. “It was home,” Longway tells me. “It was a place where you had to place the tough guys on one side and the soft guys on the other.” Longway says he became a big brother to Jeffery, but declines to detail the problems he helped solve.

The gambling culture of Jonesboro had a strong influence on Jeffery, Longway says: “His dad did a lot of gambling, so of course he was gonna pick up on it, at a real young age.” The activity also led to a tragedy: a 2016 GQ profile revealed one of Jeffery’s older brothers, Bennie, was killed during an argument sparked over a game of chance. Jeffery was a child. “That was the person [Jeffery] looked up to and wanted to be like,” Longway says.

But there are more dimensions to his origins than just trauma: Jeffery was a young boy who was always drawing cartoons, who strove to make high fashion a part of his life. “I used to hustle to get Bally shoes,” Thug murmurs. “Those’re, like, real memories.” He was seven when he first listened to Tupac Shakur songs like “Thugz Mansion,” but 10 when he first heard them — it was a discovery that helped set the course of his life. “Going through things [like] deaths, victims of the streets, heartbreak, and just finding out he got these type of songs, I always double back. [I’ll] play them again right now.”

Thug released I Came From Nothing in 2011. But its sequel I Came From Nothing 2 — ‘00s Lil Wayne-indebted, occasionally psychedelic, and resilient to this day — forced the rap world outside of Atlanta to take notice. Who was this tattooed, Blood-claiming gangster with a model’s gait and painted fingernails? The rock star bringing an Alice In Wonderland sensibility to trap music? Gucci Mane took Thug under his wing, and Thug rewarded him with fierce loyalty — Thug would go on to sign a production deal with Gucci Mane’s 1017 Brick Squad imprint in March 2013, a management contract with Birdman’s Rich Gang, and a meager $30,000 deal with APG in the fall of 2013. He finally landed at 300 Entertainment, his current home, in April 2014.

“Stoner,” released in 2014, marked the first time Thug’s squawks, coos, and lines both beguiling and memorable hit the Billboard charts. He wore dresses and tutus in photoshoots, called other men “bae” and “lover,” and said “there’s no such thing as gender” in a Calvin Klein ad. People called him gay despite his denials, an engagement to Jerrika Karlae, and an eye for heterosexual passion more colorful than almost any other rapper — Thug’s lyrical erotica would win an Oscar if someone filmed it. What would be tabloid blog fodder for other artists became groundbreaking reconsiderations of masculinity in hip-hop, simply because the music and artist behind it were so compelling.

That last detail deserves an underscore: there is no one making music like Young Thug. Alex Tumay began working as an engineer with Thug in 2013; over the phone, Tumay says he and Thug were recording 80 songs a week at their peak during the Rich Gang era. And Thug doesn’t write, ever. “[Thug will] hear [a beat] and he’ll know what he wants it to be,” Tumay says. “There’s not really anything else like it.”

“We don’t dwell on the influence we already pushed out. We trying to ambush the galaxy.” —Young Thug

Thug’s hyperactive workflow has lead to consternation with his label. A clip from the 2016 CNBC docuseries Follow The Leader shows Thug butting heads with 300 co-founder Lyor Cohen. “This year I want 10 number one singles,” a vexed Thug says. Cohen responds in the deliberate, slightly vengeful tone of a teacher addressing a stubborn pupil: “You just record so many songs and leave them like little orphans out there. You have to come back to them.” Neither man budges. Thug’s album Hy!£UN35 (pronounced High Tunes), scheduled for release in 2016, never dropped. Cohen left 300 in September of that year.

Behind-the-scenes friction did not prevent Young Thug’s influence from spreading across hip-hop, and he took notice. In an Instagram Live session last June, Young Thug wanted his flowers, and came for them with a scythe. His body was tense with frustration when he snapped: “I’m the drip god. I created this shit. I made y’all tighten y’all jeans up... I’m the master.”

Nowadays, Thug wants to appear less concerned with getting copied and left behind. “I feel like I started a lot of things,” Thug says. “[But] I don’t try to downplay nobody career. I ain’t make they career, I just made a lot of people not be scared to be them.” He rubs his eye. “I just like to see people do what they want to do.”

One of the clearest markers of Thug’s influence and foresight has been the success of his label, YSL Records, and its artists who fall directly in his lineage. Next to Thug, Gunna is the label’s biggest star, a satin-voiced protegee who shared a multi-platinum single in 2018 with Lil Baby, “Drip Too Hard,” from their blockbuster collaborative mixtape Drip Harder. Lil Keed, a 21-year-old Atlanta native, is being pushed hard as the city’s next big act — his well-received project Long Live Mexico included features from Lil Uzi Vert, Gunna, and Thug himself.

“When I started signing people, I stepped out of being an artist,” Thug says. “I start noticing what made me happy, what type of music I like from my artists and then that’s what made me better, like, ‘Okay, now I’m a fan. Now I see.’ So now, I deliver for fans.”

Thug wants two things in an artist he works with: “pureness [and] work ethic.” I ask if a unique style is important, and he shakes his head. “Anything in the world got style. A roach got style, the way he run, the way he hide, the way he eat. Everything has style, so I don’t care to look for that. I mean, I love it, if you got a unique style, [but] it’s just an add on.”

I ask Thug if he’s gotten advice on dealing with the pressures of breaking ground from Gucci Mane or Future, his idol-turned-rival-turned-brother in music. He smirks. “All the trendsetters know the same exact things, Gucci, Future, anybody you thinking of that’s trendsetters, the same things they know, I know,” he says. “So they don’t got to tell me how to deal with it ‘cause I know exactly how to deal with it: just keep influencing. We don’t dwell on the influence we already pushed out. We trying to ambush the galaxy.”

It’s 20 minutes before Thug is scheduled to perform, and there’s a problem. To get behind the stage, Thug will be required to walk about 100 feet through the festival grounds, and then cross two lakes on two separate dinghies. Thug’s team is worried about grabby fans. Extra security encloses Thug as we gather around the tall barrier separating Tomorrowland’s guests from its crew. It feels like we’re about to get a guided tour of a volcano.

An opening emerges and we all flood out. I glimpse a lot of cut-off jeans, body paint, and a few flags of different countries swathed around shoulders. There are stares and a call of “YO, THUGGER,” but no swarming. We’re hustled behind another fence sealed off from the public, and walk a narrow dirt path to the dock. One after the other, each person boards the first of two motorboats that will take us towards the stage. Thug perches on the front and faces the driver, looking bemused, like a rare flightless bird.

The strategies to put Thug on public view have regularly been thwarted, sometimes catastrophically. In May 2015, several dozen unreleased songs by Young Thug and Rich Homie Quan spread across the internet. The tracks were recorded during the sessions for Rich Gang, the Quan/Birdman/Thugger collaboration that yielded one tape, Tha Tour Pt. 1, and “Lifestyle,” a song widely regarded as a modern classic. The leaked music was never officially released, marking the first time Thug’s career would be derailed by unauthorized uploads of his music.

To my surprise, Be EL Be recommends a leak collector for me to speak with. He goes by the username SabSad. “He helps [us with] taking down leaked songs,” Be EL Be writes in a text the following week. “Not sure if he hacks. But he knows everything on how the songs leaked. He’s been down for a long time.” A few days after I leave Brussels, I call him.

“Anything in the world got style. A roach got style, the way he run, the way he hide, the way he eat. Everything has style, so I don’t care to look for that.” —Young Thug

SabSad’s name has been attached to the Rich Gang leaks, but he strenuously denies ever hacking music. He says the Rich Gang material originally leaked in late 2014 from “somebody close to Thug.” A few collectors compiled all the music in a private Google Doc, and when one of them decided to upload the trove to leak website Atrilli, the files became public knowledge.

The methods hackers employ to steal Young Thug’s music are elaborate. Both SabSad and Be EL Be tell me that Thug songs have been stolen by SIM swapping — a method of fraud that gives the hacker access to texts, including any messaged audio files — and by hackers who book a session at a studio Thug has posted on Instagram. Potential buyers will pool their money together to purchase a leak from the hackers, either on invite-only websites or on the chat service Discord. Once purchased, the owners will choose to either keep the song for strictly personal enjoyment, resell it themselves, or just upload it for anyone.

Despite the sophisticated nature of these thefts, and the fact they are a problem for many other high-profile artists, Thug is unfairly perceived as an artist who is careless, and even disrespectful, with his own music. “It pushes this narrative that Thug is the reason that these songs leaked, but that’s not the case,” SabSad says, mentioning that Thug’s security is now better than most artists’. “Ninety percent of the time [the leak]’s not from Thug’s side.”

The ripple effect of a leaked song is difficult to quantify, but it goes far beyond an insular moment of gratification. “I fully understand wanting the songs to come out,” Tumay says. “[But] whether you want to admit it or not, the more you leak music, it lowers the perceived value because there’s so much free music out there. Then, the perception changes of the music that is released on albums and projects.” There are also the livelihoods of the behind-the-scenes personnel who work on leaked music to consider. “You’re hurting dudes that are getting paid hourly,” Tumay says. “Dudes who are only getting paid when the song drops. That doesn’t happen if the song leaks.”

When I ask Thug about his leaked music, he tries to appear nonplussed, but an irritation flares in his voice. “I feel good about [the leaks],” he says, clearly not feeling great about the leaks, and uses a line Thug leak collectors often employ: “I probably never would have put [the leaked songs] out, so I’m just happy that they was out.”

The extent of the leaks and the narrative surrounding them obscure the reality of an artist with a tender, prideful relationship with his work. In Brussels, Be EL Be mentions that Thug has a tendency to drop his favorite songs rather than his best. I bring this up to Thug during our conversation, and his eyes narrow. “There’s time for everything, you know? Some music’s too advanced. I don’t want it to go over their heads. Some music is down to earth. Some music is perfect for whatever time it is. Some music is too big for time.”

The increased security around Young Thug’s music couldn’t have come at a better time. Aside from So Much Fun, Thug has been working on another album called Punk. When we speak in late July, Thug says he hopes to release Punk in “two months,” and he speaks with more enthusiasm about this project than So Much Fun. “It’s most definitely touching music,” Thug says. “It’s music that the world is going to embrace.” The title, both pejorative and an honorific, has a personal meaning for him: “[Punk] means brave, not self centered, conscious. Very, very neglected, very misunderstood. Very patient, very authentic.”

Young Thug wants Punk to mark the reentry of what he calls “real rap” into the culture. “[Real rap is] letting people in, letting people know what you go through. Let them know that you the same,” he says. Thug has never shied away from appearing vulnerable in his music. But his social media presence has become more explicitly revealing — in 2018, he tweeted “At war with depression,” and recently shared a clutch of Instagram videos containing prayers for those close to him.

“I just want to open up,” Thug says. “Let people know that I’m not just a rapper, I’m a human being. Let people know whatever they go through, I done been through or somebody done been through it. Those are the things that make people grow. People that want to commit suicide, you might give them another chance.”

Like every beloved popular musician with substance and staying power, Thug’s fans classify his catalogue into eras. Some fans use the changing color of Thug’s dreads over the years to indicate their favorite releases (the blonde dreadlocked-era Thug is frequently mentioned as a particular hot streak). Punk is the “Poet Thug” era, Be El Be says; he’s even making more of an effort to enunciate his words. Thug speaks with urgency when he says he wants to speak against “wickedness” he sees every day. “The world is big on the Internet. If we can get another rapper like Tupac that the world can shine a real light on, they can really teach us. They really can teach the kids.”

On stage at Tomorrowland, Thug glides back and forth like a marble statue that decided to come to life for 40 minutes. An impressive crowd has gathered underneath a tent with a halo of fake purple wisteria on the roof — the space fills with the sound of singing whenever DJ Cash dips the volume of the track he’s playing. Whatever uncertainties there were about Thug’s success at an EDM festival melt away.

As he performs “Check,” a series of fireworks go off unplanned in the distance behind stage right, exploding just as the beat drops into the hook. Only a few people seem to notice it, but those who do are transcended. In this moment, the words are charged with a new joy, like a new piece of ourselves was signed back to us: Got me a check, I got a check / I, done got me a check, I got a check.

Young Thug wants 2019 to be his crossover year. Selling 10 million records with “Havana,” Camilla Cabello’s 2017 single featuring Thug, hasn’t been enough for him to fully ascend to pop-rapper status. This year, he has songs with Ed Sheeran (“Feels”) and Post Malone (“Goodbyes,” which debuted at No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100). “I always want to rise,” Thug says. “I always want to go to the next level. It could be a big step or a smaller step. Just don’t want it to be the same.” To that end, he wants to leave beef in the past: despite claiming in January that Lil Wayne had launched a lawsuit over Thug’s mixtape Barter 7, Thug now insists that’s done. “No one’s suing me,” he seethes with no small hint of disgust at this line of questioning.

MOWALOLA vest and leather pants, CHRISTIAN

LOUBOUTIN BY MOWALOLA shoes, YOUNG THUG'S OWN jewelry.

MOWALOLA vest and leather pants, CHRISTIAN

LOUBOUTIN BY MOWALOLA shoes, YOUNG THUG'S OWN jewelry.

What does Thug think he has to do to take his career to the Michael Jackson-level echelon he dreams of? “Wake up and breathe,” he scoffs. “There’s nothing I’ve got to change. I just got to keep succeeding and keep working, just doing my best.” In September, he’ll launch a co-headlining tour with Machine Gun Kelly, the Cleveland it-boy/rapper. Reaction from Thug’s fanbase has been mixed.

I suspect the music industry is too small for Thug. He is the latest in a long tradition of black geniuses who are wholly incompatible with its petty bureaucracies. Thug wants to be the biggest artist and CEO on Earth. Is that possible for the underdog that he is, for the subversive that he was born being, to do on his own terms? To be a Young Thug fan is to hope against hope for pure talent to win the day, and that the ever-present sunset on the skyline represents the end of the day for the fake artists sprouting up like so many bot-bought reblogs.

The longevity of Thug’s skills shields him from being crushed by the machine. His status as a pioneer is undisputed. “Thugger made it OK for everybody to think different,” Post Malone writes in an email, crediting Thug for broadening rap’s horizons. “He is hip-hop, but not afraid to do country, pop, Latin. He makes it okay to be fearless as fuck and just be yourself. He showed you don’t have to listen to anything anyone says. He’s gonna be here for a long time, doing what he does.”

Back at the hotel after his performance, Thug is presented with a gift. It’s an eight-foot landscape oil painting depicting members of the YSL Records family and close associates as soldiers, wearing Napoleon-era French uniforms. All the characters look to Thug, who rides a rearing horse in front of the Sphinx — on the left, a heavenly Nipsey Hussle stands with the battalion. Thug is genuinely moved, studying the canvas and brushing it a few times with his hand. He daps every person involved in the painting, and gets their Instagram handles so he can tag them when he shares it.

“The people that don’t get a lot of likes,” Thug says, “the people that they music don’t buzz a lot, nine times out of 10 they, like, too ahead.” He pauses. Dim light bounces off his face tattoos. “So you can listen to an artist and be like, ‘Man you sound wack. Shit sound like old rap.’ It’s just ahead of the time, it just ain’t came back around yet. It’s all just all the turn around. So you can never really be behind the line, you always can be in front of the line.”

SPIDER jacket and pants, 3.PARADIS sweater, YOUNG THUG'S OWN t-shirt, DSQUARED2 boots.

SPIDER jacket and pants, 3.PARADIS sweater, YOUNG THUG'S OWN t-shirt, DSQUARED2 boots.

Hair by Ben Talbott. Make-up by Mata Mariélle. Style assistants Willyum Beck and Jack O’Neill