Marty Perez

Marty Perez

Twenty years is a long time to be working on any music story. The nature of the industry is change; the old becomes passé, and only the newest has relevance. This maxim was well known when critic Jim DeRogatis began his reportage on R. Kelly in November 2000, but he couldn’t have predicted it would take nearly two decades for the world and law enforcement to accept and act on the singer’s alleged sexual assaults of tens of women, many of whom were younger than the age of consent when the alleged abuse began.

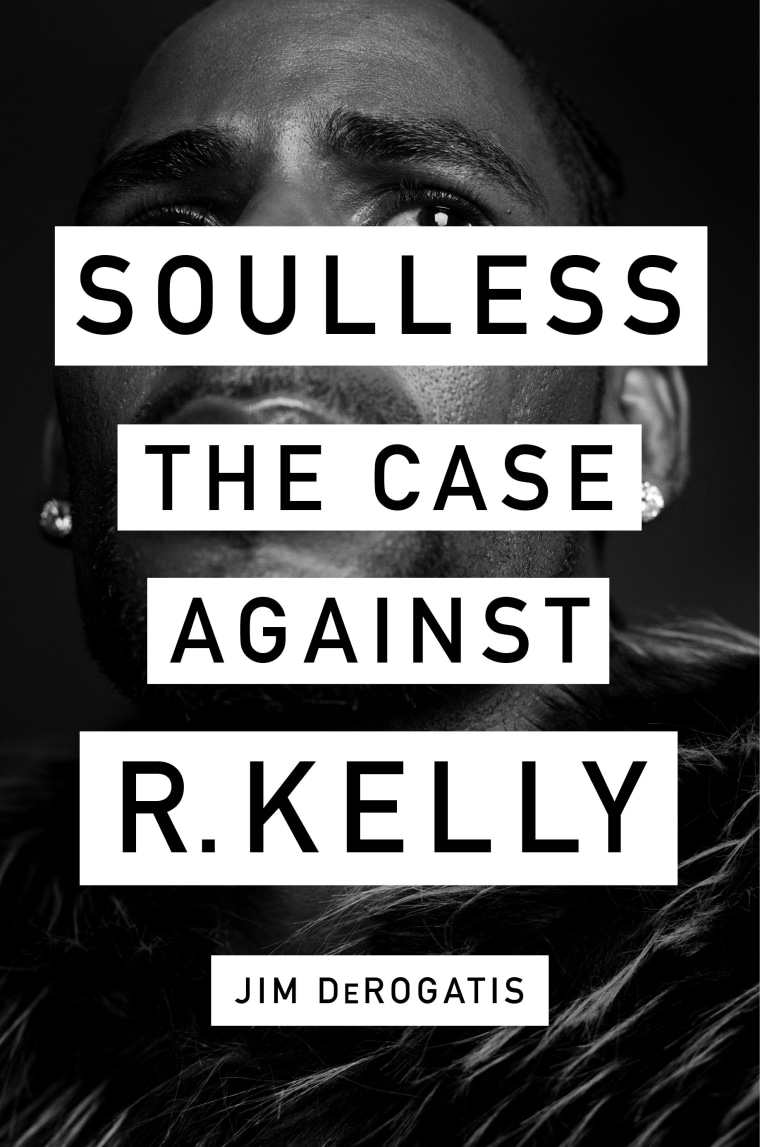

What compelled DeRogatis to the long years of both death threats and indifference were the women themselves? “When a young woman who’s been sexually assaulted at age 15 is sitting with you and doing the hardest thing that any human can do, you are not an unfeeling automaton,” he says. His compendium of that work, Soulless: The Case Against R. Kelly (June 4, Abrams Press), chronicles this period, also including foundational experiences in his own life that brought him, a “fat, white rock critic,” to interview scores of young, black women; their friends, and their families in an effort to tell the world about a man he says is “the biggest predator in the history of popular music.”

Thanks in large part to the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements, the world is different from when DeRogatis began, and his 2017 Buzzfeed story, on the alleged sex cult Kelly runs, found fertile ground. Kelly now faces 21 indictments from the state of Illinois even as a federal investigation looms. Civil lawsuits abound, and Kelly, self-described as a “broke legend,” seems to be nearing the end of his rope. Still, DeRogatis persists. Kelly, after all, isn’t the story. Instead, it’s the women themselves, DeRogatis says. Their bravery to speak compels his work. Despite the years, he isn’t planning on stopping so long as they keep searching for someone with whom to speak. After all, a critic’s job is to listen.

Your first piece of investigative journalism on R. Kelly was published in 2000 for the Chicago Sun-Times. It’s hard to comprehend that something like this would take so long before the public and law enforcement would take notice.

It’s pretty frustrating, but I don’t think it’s unique in journalism. I’m certain [Bob] Woodward and [Carl] Bernstein [reporters for the Washington Post who broke the Nixon Watergate scandal] felt that way — and not to compare my story to that. How does it feel for the many journalists exposing what I believe are very true accusations by Dr. Christine Blasey Ford against Brett Kavanaugh? And then you look at pictures of him on the Supreme Court. We do our best as journalists and you don’t give up. Sometimes it takes a long time, a frustratingly long time, for society and the criminal courts to catch up.

You talk about your early history in this book, growing up in New Jersey and training as a cub reporter prior to moving into music criticism. Why include so much of your own back story?

Well, I agreed with my editor, and he thought it was important to include where I came from and how I got on this story. We do not live in this world of false objectivity. Nobody is objective. You are fair as a journalist, and unceasingly so, but you have your opinions. When a young woman, who’s been sexually assaulted at age 15, is sitting with you and doing the hardest thing that any human can do, you are not an unfeeling automaton. You are professional; you verify; you get a second source. But, obviously, this was an emotional story for me, and it was necessary to explain why it meant so much for me. As a decent human being and as someone who believes in the power of music, it’s all part of the story.

One of the lawyers you quote in your book says that this story has “poisoned” you. What impact has this story had in your life?

I think I was as slow as many journalists to realize what was going on. Abdon [Pallasch, DeRogatis’s cowriter at the Chicago Sun-Times] and I were almost a decade late when we published our first story in November 2000 — this behavior starts in 1991, and the first lawsuit was filed in ‘96 and Aaliyah in ‘94. We were late! And still, for 20 years, we were the only ones. I will never be able to understand how it is that journalism and criticism failed so epically here.

Every critic is first and foremost a reporter. The fact that so many critics could write “despite that unpleasantness, R. Kelly is a genius” and not dig any deeper. The fact that the newsrooms in Chicago, except for the Sun-Times, are ignoring this man — he’s a multi-millionaire, he’s in the world spotlight, he’s singing at the opening of the Winter Olympics and the FIFA [World] Cup. What more do you need? He’s a celebrity, and yet “it’s just music.” Those three words are the most insulting thing you can say to me.

You’ve received pushback from R. Kelly and his fans for years, and you even mention a moment in the book where someone shoots into your home during your reporting. As you’ve approached publishing this book, what has changed?

This is different. The amount of hatred I’ve seen on social media, Twitter and Facebook, in the last couple of weeks pales in comparison to anything that I experienced in the last 18 years. It’s really frightening to me. Because at this point, post-Surviving R. Kelly, post all of this reportage, post a second round of indictments, an ongoing federal investigation, I don’t think people can claim ignorance anymore. I think the people supporting R. Kelly and saying horrible things and posting pictures of my ex-wife and video of my daughter singing, they know and they applaud Kelly. That really scares the fucking shit out of me.

How have you dealt with the stress of that?

Let me put that in context: I cannot imagine the shit that Oronike [Odeleye] or Kenyette [Barnes] of ‘Mute R. Kelly’ are getting. I’m aware of it, because I’ve spoken with them, I’ve spoken with dream hampton. If I’m getting this, I don’t know what it’s like for these women, especially the ones who so bravely spoke out. It’s got to be living hell, which makes me admire them even more.

R. Kelly leaving the Leighton Criminal Courthouse in Chicago on June 6 after appearing in front of a judge to face new charges of criminal sexual assault.

Nuccio DiNuzzo/Stringer/Getty Images

R. Kelly leaving the Leighton Criminal Courthouse in Chicago on June 6 after appearing in front of a judge to face new charges of criminal sexual assault.

Nuccio DiNuzzo/Stringer/Getty Images

You’re a white man investigating a black man. How have you dealt with accusations of racism motivating your work? And how did your race affect your reporting within a black community?

To me and to Abdon, from day one, yes, we were writing about a black man, but we had met so many of these black women and the people who loved them. Didn’t they count? They weren’t hurt? They trusted a fat, white rock critic and this little leprechaun-like Irish/Polish court reporter in their living rooms. We never were twisting people’s arms. People were eager to tell this story, and nobody else was listening. It didn’t seem to matter to these hundreds of people that we were white, and it never mattered to us that their daughters were black. I never saw the difference between my daughter and these poor girls.

You write in the book of how all pop icons make the myths that surround them. Do you think that these people who threaten you online are still able to believe in Kelly’s myth despite hammer after hammer to the contrary?

I think the myth has dropped away. Carey Kelly, Robert’s younger half-brother, says in the book, “He’s speaking to muthafuckas on their level.” They think the way [R. Kelly] does. It’s frightening to me that so many people have such disrespect for women that they can defend this man who I believe is the biggest predator in the history of popular music — which is certainly saying something.

But I think right now, with #MeToo and Time’s Up, we are being forced to examine the context of art we love. I can watch Midnight in Paris by Woody Allen. I am well aware of what Dylan Farrow has said. I can never watch Manhattan — it’s about a middle-aged comic dating a high schooler. I think there’s this deep emotional connection [with music], and you are reluctant to turn on the person who created it. I understand that. I don’t think there’s a right or wrong. If you tell me, “I know what he’s done. I think he should be stopped. But I still can listen to R. Kelly,” I don’t think you’re wrong. I have my answer; you have yours. I think these questions are the lasting legacy that #MeToo and Time’s Up will have. There’s not a right; there’s not a wrong. Each of us will have an answer.

You describe Kelly’s crimes as “a different magnitude” when compared to other artists’. Why is it difficult for some to understand him as this epitome of predatory behavior unique among musicians?

D.: I’m talking strictly numbers. Lori Mattix and Jimmy Page [of Led Zepplin], Priscilla Beaulieu and Elvis Presley, Myra Gale Brown and Jerry Lee Lewis. I can name others. But with R. Kelly, I know the names of 48 young women. Many of them are on the record, there are others that aren’t, and I believe there’s got to be many, many more. I think a single sexual assault is nothing to minimize, so I’m not saying this is a contest that he won. I’m saying it’s disgusting: In full view of the world, while selling 100 million records, he’s gotten away with leaving hundreds of lives damaged in his wake.

Even as you and I talk, a couple of miles away from my home office here, two young women in their early 20s are being held — according to their parents — brainwashed, against their will, in a cult. I thought those words were exceedingly dramatic when I first heard them in November 2016, and after 15 on-the-record sources, numerous off-the-record sources, and nine months of reporting later, I had to say that I can’t think of better words than “brainwashed” or “cult.” These words have been there since the beginning [of my reporting in the early Aughts]. This is such a strange 30-year story of horrible abuse of women that it’s going to take us a really long time to catch up with just how disturbing it is.

You’ve reported this for decades. How does it feel to have this story largely define your career?

I don’t know. I’m at episode 706 of a public radio show, I’ve written 11 books. When Kelly sings in “I Admit” that “off my name, [DeRogatis] done went and made [himself] a career,” — eh, it’s a story. Sometimes you choose your stories, and sometimes they choose you, and you’re not a journalist if you give up on them. I’ve told a lot of stories. But as a critic, I’ve always felt if you don’t think that the very best record you ever hear you’re going to discover next week, get out of the fucking way. You live for the next record and the next artists and that next concert experience. There are other books to be written, and Kelly is part of it.

You mention that part of the reason these abuses have gone on for so long is because of civil suits settled out of court, but you also mention you’re fine with these women profiting of their stories as some small means of recompense. How do you balance these two views?

That leads to the quote, “Nobody matters less in our society than black women.” I’ve only ever been amplifying them saying that. Everybody in Chicago, and nationally, and internationally failed these young black women: the courts, the schools, some of their parents, civil attorneys, the criminal system, the police journalism, criticism. Everybody failed these young women.

I can’t say they’re wrong to go and be on Lifetime or take R. Kelly’s money or write a book — I’ve written a book. I didn't want to live in this darkness any longer. But I think there was a need, because still, with ten counts of Illinois indictments and a federal investigation looming, I think people don’t realize the scope of 30 years of this man’s crimes in full view of the world’s spotlight. I don’t think the big story, still, has registered with people.

Coming near the end of this narrative arc, are you optimistic about what will happen to Kelly? Will justice be served?

No. The Illinois case is really weak because many of the incidences are old and Reshona Landfair [the state’s key witness in Kelly’s child pornography trial] is not cooperating with the state, just as she didn’t in 2008. The three victims—I’ve spoken with two of them—will be torn apart, their reputations are going to be dragged through the mud, and all of their motives are going to be questioned. This is rape culture. I have higher hopes that the federal investigations are looking at what we said in story number one in 2000: a pattern of behavior that is 30 years long. But even that is heavily weighted. I had some optimism that special council Robert Mueller would expose crime in the White House, and that didn’t happen either. Brett Kavanaugh sits on the Supreme Court, and we have half a dozen states that are trying to roll back the clock on abortion to pre-1971. It’s all well and good to struggle to be woke. I don’t know if we are. Mute R. Kelly hit him where he lives. In shutting down his ability to make money, the only thing that may stop him is that he’s broke.I am super cynical about the justice system. I just hope he stops hurting women.

If it’s not over, does that mean your work isn’t yet over?

D.: There are more journalists on the story now, and I can sit back and be a commentator. On the other hand, if the phone rings and it’s another young woman who says, “No one has listened to me. Can I talk to you?” I’m going to take that call. I still get those calls. I got one this weekend. How can you be done? I guess what I mean to say is, I’d like to be done. If Reshona Landfair calls tomorrow, I’m going to take that call.