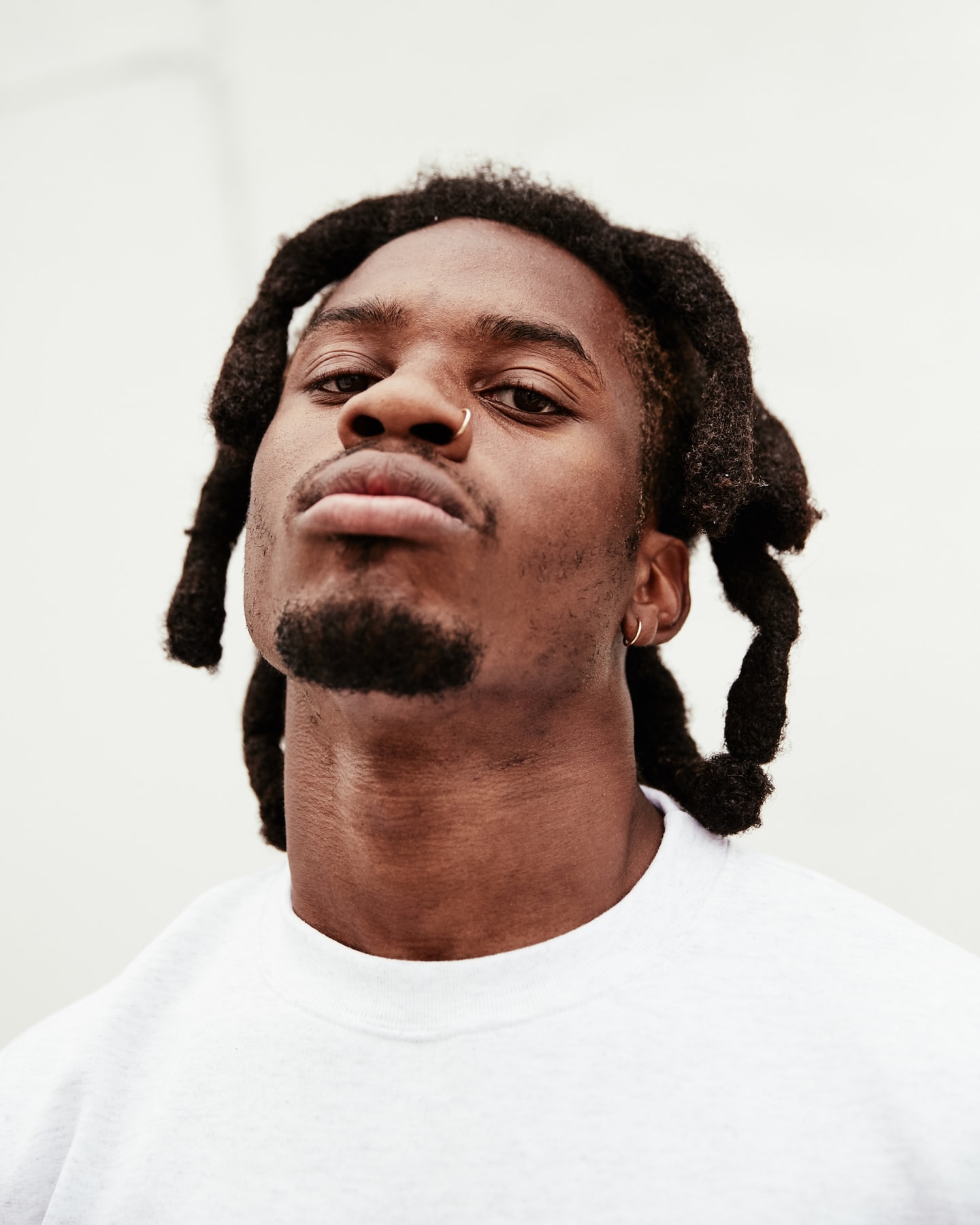

It’s a Monday afternoon and Denzel Curry is standing alone on stage in an otherwise empty rehearsal space, which has been blacked out and is so cavernous that you’d imagine it would echo. But the sounds are deadened by the walls; outside the padded door is an anonymous loading dock and then a bright, sweaty Hollywood afternoon. Inside, the rapper is testing out some new equipment and making last-minute tweaks to his setlist; it’s less than 24 hours before he’s scheduled to leave for tour, where he’s supporting Billie Eilish on 18 dates across Canada and the U.S. through the middle of July. He’s wearing a yellow hoodie, black pants, and sneakers, rapping songs that have yet to be released with roughly half the animation you assume he would give them in front of a crowd.

Curry is 24 years old and performs under his given name. He was born and raised in Carol City, a section of Miami Gardens about 20 miles North of South Beach. (Sixty years ago Carol City was an unincorporated farming community; by the mid-2000s it was being used as a case study for threats to teenaged lives.) At the beginning of this decade, he distinguished himself as one of the most promising members of Raider Klan, the rap collective founded by the troubled but visionary producer SpaceGhostPurrp. Raider Klan’s music was conspicuously underground: it was buried under concocted tape hiss, mixed so that you could hear all the seams, and given cover art and album titles so gaudy and Gothic as to make mall attire seem genuinely sinister. The group was in many, often obvious, ways a tribute to early- and mid-‘90s Memphis rap, but it went beyond homage and is being bitten to varying degrees by artists famous and obscure to this day.

The music Curry has made since splitting from the Klan in 2013 has spiraled away from his stylistic origins, first gradually and then rapidly. Some records, like his 2013 debut album Nostalgic 64 or 32 Zel/Planet Shrooms, his double EP from two years later, seem like logical extensions of his earlier mixtapes. Then came Imperial, which was urgent and minimal, and last year’s Ta13oo, a dark, fraught record that showed off Curry’s abilities as a singer nearly as often as it mined what seemed like a tortured psyche.

Despite being fluent in a handful of today’s most popular styles — and despite being more acrobatic and ambitious than most of his peers — Curry is rarely given credit as the synthesist he is. Instead he often finds himself on the receiving end of backhanded compliments from critics and fans, praised as being good for a Florida rapper or reduced to a product of the state’s SoundCloud scene. (The Apple Music page for Imperial describes Curry as “A Miami rapper with an East Coast MC’s furious mentality.”)

ZUU, his new album — out today — is fundamentally different from Ta13oo. The last record “was me coming from a depressed place,” Curry says. “This one came from me being homesick.” He originally wanted to call it Axis (“because it was gonna have everybody on tilt,” he says, laughing) but Curry eventually realized that he needed a title that served as a reference to his hometown, which was figuring largely in the record. “This is some real Miami stuff,” he says. ”You can tell from the intro all the way down: it goes from the sounds of where I grew up, to what I was raised around, to the people I was raised around, to the sounds that pretty much shaped the person I am. And then eventually, when you get to the last track, it’s the sounds that we do now.”

In conversation Curry, who is intense and introspective but has a drama student’s practiced ability to control a room, usually seems poised. But he does admit that the prospect of hitting the road with someone who’s quickly become one of the world’s most famous teenagers is daunting. “I’m just nervous as hell,” he says with a grin. “Billie sat me down and was like ‘No, bro, my fans are the most understanding fans ever.’ I was like, ‘Your fans are seven!’”

You leave for tour tomorrow. How are you feeling about the rehearsals?

I like the rehearsals. Now that I know what [inner-ear monitors] feel like, I’m just like, OK, fuck yeah! I don’t have to yell as much, and I most likely won’t lose my voice. That’s a huge positive. Doing different voice changeups, the same way my music does it, so I’m not yelling the whole time.

It’s disappointing when artists sound one way on a record and then fuck it up live.

Yeah, I can do both. But I don’t know what it sounds like from the crowd’s perspective. When I go to a show I’m like, What’re [the artists] gonna do? And most rap shows I go to it’s...you know. I go there to hear my favorite song, but I don’t see them perform. If I go to see someone like Tyler or Gambino, they perform. Kendrick performs. I seen Beyonce for the first time, it was amazing. I don’t even like my rap shows to be rap shows.

What do you like them to be?

Shows. Just something that’s entertaining. I don’t know if you know, but back in Carol City I had theatre class...theatre is the thing that I was interested in, that’s why I’m into movies and shows and stuff like that. Cartoons and stuff. Watching how everything is put together like a play. When I saw Kanye West perform Yeezus for the first time —

With the mountain.

Yeah. That’s what made me want to step my show game up, even though I didn’t have no money to do it. All I had was a DJ, a mic, possibly a projection that would cost $100, $200 at the most.

How did you link up with Billie Eilish initially?

She was a fan. She’ll tell you to this day, if you were to ask her: ‘I’m a fan of Denzel.’ But it went from us trying to work together, to us building a friendship, and then eventually back to us working together. She ended up being on “Sirens” from Ta13oo. But before “Sirens” was even thought of, like two years back, in 2017, her management hit up my management saying she wanted to work with me. We get up in the studio: It was her and her brother Finneas [O’Connell]. That was the first family member I met. Then I ended up meeting her father. Then eventually I ended up meeting her mother. Then I met her best friend. They’re all cool people. Her dad came to the studio when we was working on “Sirens.” We was all there: me, her, [Maryland rapper] IDK, her dad. We made two tracks. “Sirens” ended up being on the album, and there was another track that IDK was drilling her through. We still have that track, we just never completed it. Her vocals are on there, but ours aren’t.

“I feel like I’m part of that lineage of Florida rap that was undiscovered. And then when they finally discovered it, they would be like, Damn, that’s weird.”

The new album comes out this week. You wrote and recorded most of it out here in L.A.?

Yeah.

How do you like the city?

I like it, I’ve been [living] here for like two years. But after a while I start to miss my family, start to miss old friends. Stuff that I used to do when I got super-depressed. And I’m not gonna make another Ta13oo. I said to myself: 2019, I’m just gonna have fun this year. I think that’s the mentality I should have when creating period. I don’t wanna be depressed. I know where I want to be.

I think that on this album you walk a fine line where, in a song like “Ricky,” you have a lot of heavier themes woven in while still being a little more upbeat, a little more uptempo.

I have to. Most people don’t know where my past is, because they only think [of] “Ultimate,” and think I came out of nowhere. No I didn’t. I was here for a long time. You just weren’t paying attention until “Ultimate.” And then you try to sweep me under the rug again, but when “Clout Cobain” came out, that’s when you became interested in who I was for real. You didn’t see me do “Ultimate” thirty-something times. You saw me do something different. [At this point Denzel lapses into Andre 3000’s lines from a song on The Love Below]: “New direction is apparent / I was a child looking at the floor staring.”

Where do you see yourself in the lineage of Florida rap?

I feel like I’m part of that lineage of Florida rap that was undiscovered. And then when they finally discovered it, they would be like, Damn, that’s weird. But [those legends I cite] accept me though. That’s the thing: Trina and Trick and Ross, all of them accept me.

What do you think it is about you that they latch onto?

Because I’m me. I’m not them. I’m not trying to be something I’m not. I’m being my motherfucking self.

Was there a song on here that was particularly hard for you to write?

“Shake 88.”

How come?

Because I’ve never made a song like that! All my songs are either introspective or simple, or just hard-headed or hardcore. Just like the typical hard shit I do, like “Ultimate.” But that was the hardest song to write. I had help with that, obviously. I ain’t gon’ sit there and be like, Oh yeah, I wrote it all. No, man. Twelve’len helped and Tate Kobang helped with that.

I was reading some interviews you did around the release of Ta13oo where you said you’d been moving around, staying in houses and Airbnbs, and had to learn how to be creative in a more transient space. How has your process evolved over the last year or so, specifically as it pertains to your writing?

Writing-wise, I just started freestyling shit. “Shake 88” is written down, but everything else, nah. [At this point Curry runs down a list of songs from the new album while saying “freestyled” emphatically after each title.] Yeah, the whole project is freestyled. I freestyled that whole shit.

What does that bring out of you — whatever’s closer to the front of your mind?

You never know what you’re gonna come out with when you just start [rapping]. Sometimes you get lost in the pad. You’re not in a constant flow state with a pad, because you’re trying to rehearse this thing, and it may sound too stiff and rigid.

Are you able to write on tour?

I take my computer and freestyle over tracks, pick the best ones, and put it together the best way I can. Is there any track that you listen to and think, There’s no way he freestyled this?

“Carolmart” is an interesting one because the flow of ideas is so linear — when I hear that I imagine you sitting down and saying “I’m gonna hit these six points.”

If you listened to “Ricky,” would you believe that was freestyled?

Sure. I don’t know what your process is like — are you going in the booth with the beat running and trying things out for five, ten minutes with the beat running, and then going back to —

Yeah. What about “Speedboat”?

I can see “Speedboat” for sure — that hook is definitely the type of thing that just comes out of your head.

But would you believe the verses are freestyled?

I’m impressed that they’re freestyled. I believe you, but —

Because it sounds like it’s written.

Sure. A lot of rappers who freestyle their songs are doing very cadence-first things, where we know to expect filler words, but most of those seem to be sanded out of your work. Was there a big learning curve for you in getting away from the pad?

Nah. During the process of Ta13oo I got away from the pad. That was after I read Gucci Mane’s autobiography, and that’s what got me freestyling. The first song I freestyled was on [LoRd Lu C N’s] The U Album, it was called “Zeltron Takeover Freestyle.” “Mad I Got It” is freestyled, except for the third verse. “Clout Cobain”? Freestyled.

Another process thing: are you doing most of these songs in a single session, or sketching things out and sitting with them?

I sit with stuff.

So when you’re out on tour, you might get some ideas down that you’ll come back to months later?

Exactly. That’s how [ZUU’s title track] got made. We just took a hook idea I did two years ago and did it a different way. We didn’t pick the same beat, we just revisited the idea. It was crunch time, we had to get this thing done.