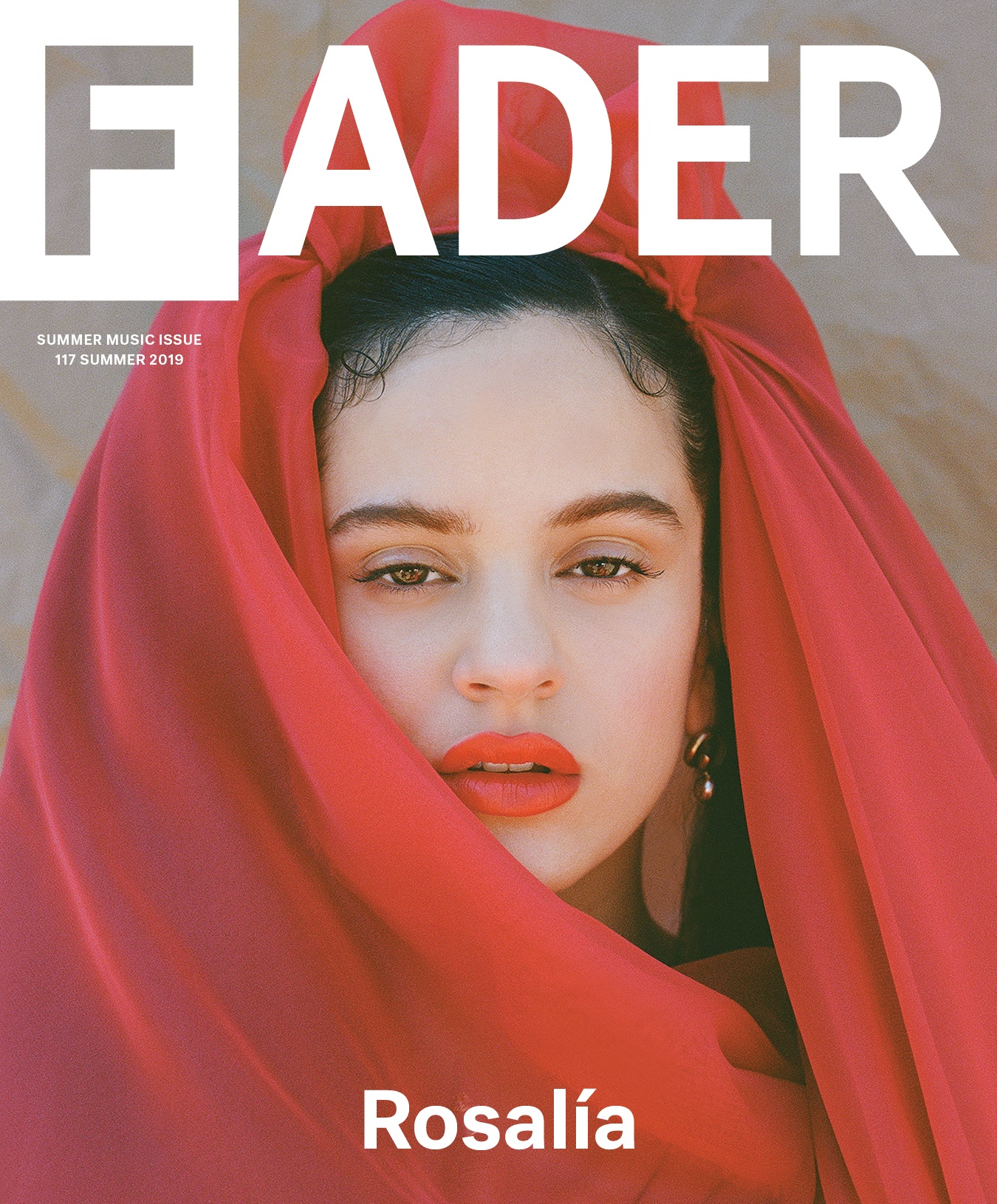

Buy a print copy of the Rosalía issue of The FADER, and order a poster of her cover here.

When I meet Rosalía on the 20th floor of a hotel in the East Village, she’s sitting across from Japanese nail art titan Mei Kawajiri, who is affixing encrusted rhinestones and miniature gold chains to her gel extensions. Suddenly self-conscious, I Iook down at my thirsty cuticles and consider asking her for an appointment of my own.

Thrifted and designer clothes spill out of scattered suitcases across the tiny hotel room, like a Burberry obstacle course. The fumes from the gel waft through the air, and Cayetana, Rosalía’s day-to-day manager, gets a whiff from the other side of the room.

“We’re getting super high right now,” Cayetana says, giggling.

Rosalía’s nails are an indelible part of her persona. They’re the subject of week-long VICE experiments, lengthy explainers in Spanish media about the tradition of nail art among Black and Latina women, and the focus of her latest video, “Aute Cuture.” Today, it’s clear she knows exactly what she wants, politely asking Mei to add a layer of hard gel to reinforce the design.

“Can we cover — like really, really, really cover — all these details? Because if not, it will get stuck in my hair,” she says, chuckling. (She says these words in English, but we conduct our interview in Spanish.)

For someone who’s fresh off her Coachella debut and just spent a sleepless month touring, Rosalía’s attention to detail is impressive. Although her outfit suggests she’s ready for a lazy Sunday afternoon — she’s sporting slightly frizzy hair and no makeup, dressed in a gray cropped sweater, plaid pink pants, and white Naked Wolfe platform sneakers — Rosalía never fully seems in repose. Even though she returned from Pharrell’s Something in the Water festival just a few hours ago and is in the midst of preparing for a two-night run at Webster Hall, she always seems to find a spare moment to rehearse one of her dance routines; contemplate a creative treatment with Pili, her sister and stylist; or unpack representations of femininity in her favorite Pedro Almodóvar movie (for the record, it’s a tie between Volver, Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios, and Tacones lejanos — not Dolor y gloria, which she recently appeared in).

At one point, I mention how much I hate taking out my contacts when my nails are done. “The only thing I admit I can’t do with my long nails done is trying to get my card out of the ATM,” she tells me.

Rosalía doesn’t like not being able to do something — and if anyone has said “no” to her in the last two years, it’s hard to tell. During that time, the 26-year-old has evolved from a budding flamenco vocalist in her native Spain into an international pop star and genre rebel, one who’s collaborated with James Blake, appeared on Kourtney Kardashian’s Instagram, taught Alicia Keys Spanish, and hung out with Dua Lipa at awards shows.

Before the stans took to calling her “Diosalía” — a hybrid of her name and the Spanish word for “God” — many knew her as the artist behind the video for “Malamente,” a song that collides the high drama of flamenco with portentous electronic synth flourishes. Created by the storied Spanish production company CANADA, the clip is a stunning collage of hard-edged choreography with allusions to bullfighting and nazarenos, the Catholic brothers who parade through the streets during Holy Week in Spain, wearing pointed cloaks.

SHIE LYU top, SHIE LYU skirt, COLLINA STRADA bodysuit, SHIE LYU bloomers, CHRISTOPHER KANE dress, LL, LLC earrings.

SHIE LYU top, SHIE LYU skirt, COLLINA STRADA bodysuit, SHIE LYU bloomers, CHRISTOPHER KANE dress, LL, LLC earrings.

Upon its release last May, the clip basically broke the internet, presenting her to the world as a meticulous audiovisual storyteller poised to modernize a sacrosanct folkloric style while asserting herself as an innovator of pop music writ large. “Malamente” refracted the theatricality of an age-old style through the lens of the future, convincing young listeners across the world that flamenco has a place right alongside pitch-shifted, Auto-Tuned vocals and luxe tracksuits. As of this writing, it’s approaching 76 million views on YouTube.

“I understand that a lot of people can’t connect with my music, because it’s a radical proposal and a personal proposal,” Rosalía says of her hybrid of flamenco elements and sparse electronics. “There will be people who can connect with it, and many that can’t. I understand the risk I take in making these decisions with my music.”

Plunge into the murky depths of YouTube, and you’ll find a video of Rosalía at 15 years old, competing on the Spanish reality TV show Tú sí que vales. It’s a tough watch. She takes the stage with just a guitar, performing a stripped-down rendition of a flamenco song. After the judges suggest her voice lacks character, she bursts into a cover of Alicia Keys’ “No One” in an attempt to prove them wrong.

It’s not enough to impress them — “I think you have a lot of potential, but you still don’t know how to bring it out,” says one panelist — but Rosalía takes their feedback in stride. “It doesn’t matter,” she says. “I’ve come here to accept critiques and learn from professionals like you. I accept your opinion.”

Now, as she gears up for a summer packed with festival appearances around the world, that video feels like a distant and awkward teenage memory, vestiges of another life.

Growing up in Sant Esteve Sesrovires, a small, mostly industrial town in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, Rosalía Vila Tobella and her sister would dream up different worlds with their Barbies and Bratz dolls. Along with their 11 cousins, they’d pass the time by covering their faces in makeup, conjuring characters out of stories they’d make up in their heads. Sometimes, they’d create imaginary schools — other times, stores and girl gangs.

As they got older, Rosalía and Pili would tag along with teenage boys who drove custom Euro tuner cars around their town. They’d cruise the surrounding industrial areas of the Baix Llobregat region, also in Catalonia, racing around the highways, gas stations, factories, and warehouses that would later inspire the setting for the “Malamente” video.

It wasn’t until Rosalía was 13 that the arrow of flamenco pierced her. It happened one day when she was hanging out by her school and heard a nearby car blasting a song with melismatic vocal runs and rhythmic palmas hand-clapping. “From the beginning, I knew,” she says, resolute and staring directly into my eyes. “I realized, This is my path.”

Rosalía knew very little about flamenco, a style of music and dance born out of the intermingling of Castilians, Moors, Sephardi Jews, and the Romani community in Southern Spain and codified in 19th-century Andalusia. She didn’t know about the sentimental howls of flamenco’s cante jondo style or its frantic zapateado footwork. But that didn’t matter. “It’s something I felt was important to my journey,” she says.

She started hanging out at the park with school friends who listened to this music, most of whom were part of the Andalusian diaspora. “They were in my environment [growing up] in Catalonia,” she says. “Or they had friends who were children of immigrants from Andalusia.” Her favorite artist quickly became Camarón de la Isla, the celebrated 1970s vocalist whose songs introduced electric bass into flamenco and earned him a reputation as a genre rebel.

Rosalía had been studying guitar since she was nine years old, when her parents gifted her one from the Andalusian city of Granada. She started singing a year later, but didn’t hire her first vocal teacher until after the car experience. At 16, she began training with the flamenco virtuoso José Miguel “El Chiqui” Vizcaya, who taught her the piano and continued her vocal training. Before long, she was singing in tablaos (traditional flamenco venues) and bars around Barcelona, sometimes without pay. “I would ask them to let me sing,” she says, getting lost in her memories of that era. “Sometimes, they’d pay me with dinner.”

Eventually, eager to study the discipline more formally, she enrolled at Barcelona’s L’Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya. There, still under the tutelage of El Chiqui, she earned her bachelor’s degree in flamenco vocal performance, graduating at 24.

Rosalía’s background in traditional flamenco performance might surprise those whose first encounter with her work was last year’s El Mal Querer, a sample- and loop-driven concept album co-produced by El Guincho, a longtime friend from Barcelona. But before Rosalía was the iconoclastic figure she is now, she was just the music school graduate behind 2017’s Los Ángeles, a largely bare-bones study in the acrobatics of vocality where she tested the limits of flamenco’s trembling melismas. After that debut, which earned praise from Spanish music critics, she started gravitating towards electronic sounds, inspired by her love of Brian Eno and James Blake.

“I was centered on [...] more acoustic sounds, but I was always listening to a lot of electronic music,” she says. “I never explain this, but I felt a clash between what I was playing and what I studied, and what I was hearing around me. My ear was trained that way — while I was growing up, playing real instruments. But on my second album, I wanted to do something that had nothing to do with that.”

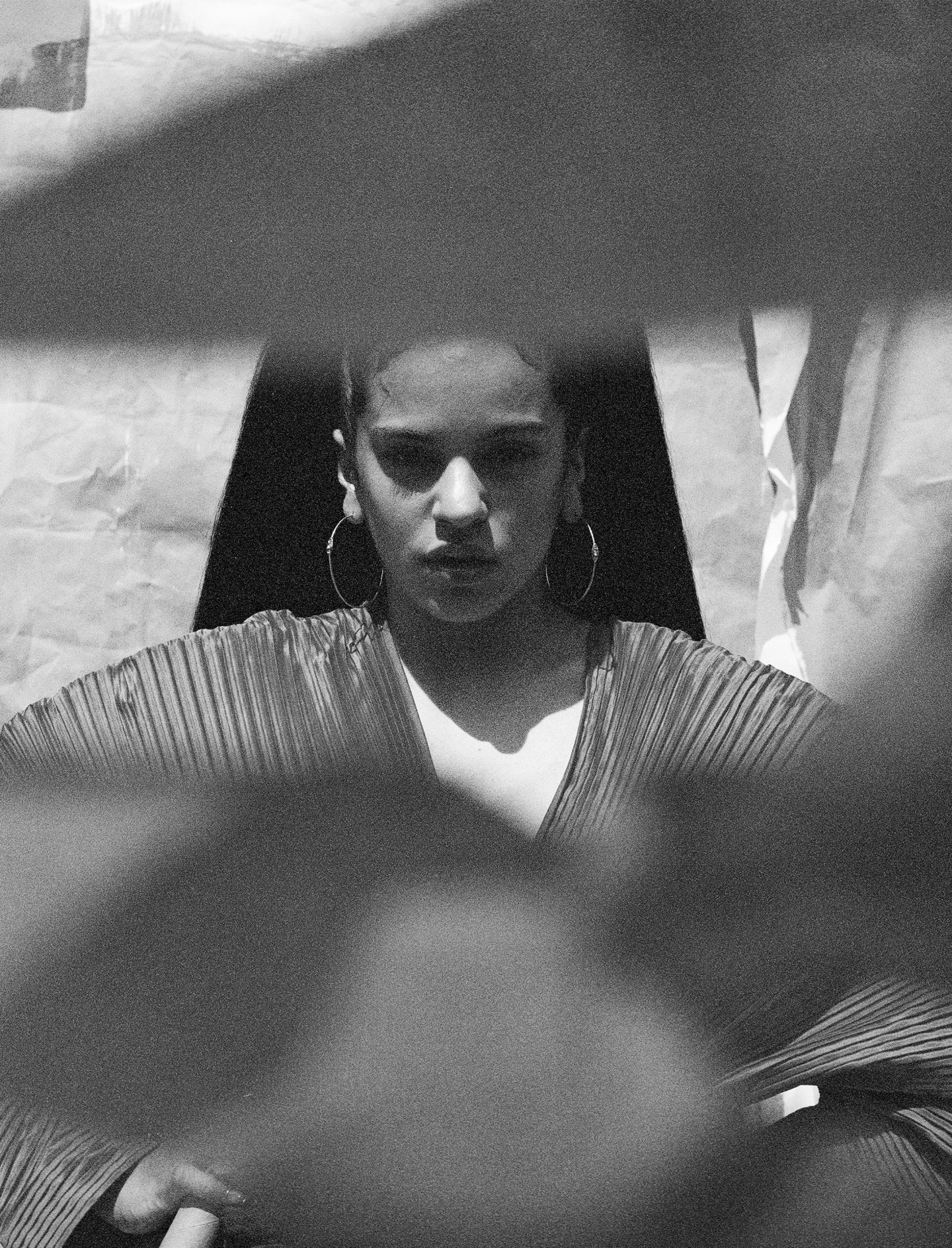

GUCCI jacket, SOLACE LONDON dress, GUCCI bow, KENZO shoes, SCOSHA earrings.

GUCCI jacket, SOLACE LONDON dress, GUCCI bow, KENZO shoes, SCOSHA earrings.

Rosalía had explored sounds outside of flamenco before, like on her feature on C.Tangana’s 2016 dancehall-lite anthem “Antes de morirme.” But El Mal Querer was something else altogether — a high-art adventure based on Flamenca, an anonymously authored 13th century novel written in Occitan, an ancient European romance language. The novel chronicles the demise of a toxic relationship, in which a woman is kept prisoner by her jealous husband, who locks her in a tower. Released in November of last year, the album was an elaboration on her university thesis, which included the development of the overall concept, the music, and a live show. The production was a radical departure from her debut, creeping around the edges of pop with frozen electronic whispers, decaying vibrato effects, and weightless R&B melodies. But according to Rosalía, the record was a study in the power of voice.

“To me, everything comes from the voice,” she says. “When I hear someone talk, when I hear someone communicate, the sound — it gives me a lot of information, more than just what they’re saying. There’s a lot of magic in voices. I love voices that are very old, very gravelly, very deep. I like metallic voices; I like velvety voices. The voices of children.” Rosalía often talks like this — in elaborate and whimsical paragraphs, as though she’s writing an artist statement in real time.

Critics hailed El Mal Querer’s juxtaposition of contemporary and folkloric sounds as a triumph. In Spain, the media commended her for reimagining flamenco for a younger generation. To many in Latin America, her left-field approach offered a welcome reprieve from the increasingly watered-down pop-reggaeton that dominates the radio airwaves. And perhaps because of the way the internet has uprooted musical boundaries and brought hyperlocal sounds to the mainstream, she’s garnered a following in the U.S. and England too. It’s a well-tread narrative in the English-language press, but there’s something refreshing about Rosalía’s intervention, probably because she’s referencing an idiom with which Anglo audiences are less familiar. Between its austere, punishing vocals and skittering, syncopated hand claps, one could argue that the grandeur and sentimentality of El Mal Querer is enough to resonate with any listener, no matter the language.

SOLACE LONDON dress, VERSACE tights, VERSACE shoes, VERSACE bodysuit, MOUNSER right earring, LL LLC left earring.

SOLACE LONDON dress, VERSACE tights, VERSACE shoes, VERSACE bodysuit, MOUNSER right earring, LL LLC left earring.

El Mal Querer opened the floodgates. Since its release in November 2018, Rosalía performed in front of 11,000 people in Madrid’s storied Plaza de Colón, received five Latin Grammy nominations; and has been spotted in the studio with Oneohtrix Point Never, James Blake, and Billie Eilish, among others. This year, she even collaborated with Peruvian-born R&B singer and producer A.CHAL on a song for the Game of Thrones album, which is as good an indicator of present-day relevance as anything else. In March, she announced a North American tour, as well as a torrent of major festival appearances across Latin America and the U.S., including Lollapalooza (the Chicago, Argentina, and Chile editions), Coachella, and Red Bull Music Festival, which is what brought her to New York this week.

The Anglophone press has often lumped Rosalía under the monolithic umbrella of Latin music. While she’s collaborated with Latino superstars like J Balvin on a few songs, most of her work draws on a tradition that has little to do with Latin American culture — despite Spain’s deep colonial roots there.

Earlier this year, Billboard interviewed her for a video segment called “Growing Up Latino.” Rosalía isn’t the first Spanish artist to benefit from this kind of imprecise marketing (think: the Alejandro Sanzes and Enrique Iglesiases of the world), but the video still rubbed some members of the Latinx community the wrong way — especially when she said that when she travels to places like Panama and Mexico, “I feel Latina.” Three months later, when I ask her how she feels about the Anglophone press labeling her as a star of Latin music, she brings up the Billboard interview as an example. Though the incident made her more aware of the pitfalls of using incorrect terminology, she’s clearly still trying to grasp the nuances.

“If Latin music is music made in Spanish, then my music is part of Latin music,” she tells me. “But I do know that if I say I’m a Latina artist, that’s not correct, is it? I’m part of a generation that’s making music in Spanish. So, I don’t know — in that sense, I’d prefer for others to decide if I’m included in that, no?”

Meanwhile, back home, she’s faced questions about her relationship to flamenco culture. The roots of the tradition are a subject of much debate among historians, but for the most part, it’s generally accepted as an art form that originated in Andalusia between the 9th and 14th century, when the Romani people immigrated to southern Spain from present-day India and Pakistan. Given its connection to that community, flamenco has a long history of marginalization attached to it. In Spain, as in other European countries, the Romani people — who identify as gitanos — have faced a long history of discrimination, social exclusion, and racist stereotyping. A 2011 study conducted by the Fundación Secretariado Gitano found that six in 10 gitanos over the age of 16 were unable to read, while 36.4% of Spain’s Romani population was unemployed, compared to 20.9% in the country at large.

In particular, people have questioned her use of gitano iconography and vocabulary, as well as the Andalusian accent she dons in many of her songs. “Malamente” in particular has been the subject of concern among some fans, given her pronunciation of “muy” and use of local slang like “illo,” an abbreviation of “chiquillo,” or kid. Some have argued that Rosalía has a platform to speak about gitano marginalization and the history of flamenco, but that she isn’t putting it to use.

At the end of 2017, gitana activist Noelia Cortes took to Twitter to express concern over Rosalía’s use of gitano symbols, describing them as a “costume” that she can wear whenever she feels like it. “I can’t stand that you have more opportunities than the gitanas that sing about their roots since they were little girls,” Cortes added. Cortes’ comments mushroomed into a larger conversation on Twitter, one that eventually made its way to prominent Spanish newspapers and music blogs.

Rosalía admits she was confused by the criticism at first, given the hard work she has put into her craft and its execution. “At the beginning, when I received that input, I suppose I didn’t understand it well,” she says. “I thought, ‘I’ve had to study so hard.’ Nobody around me was dedicated to music; there was nobody connected to the industry. I’ve had to dedicate so many years to studying and working at the same time, and it’s been very hard for me. How can someone say that, right?”

GYPSY SPORT necklace.

GYPSY SPORT necklace.

It’s been a year and a half since Cortes’ Twitter thread, and with time, Rosalía says she’s come to understand that the conversation was about her access to resources, ones that members of the gitano community may not have.

“I understood that the problem in the end was privilege — that there are people today who want to dedicate themselves to something like this, and they have more difficulty because they don’t have the possibility of studying,” she says. Eventually, she says, she recognized that gitano artists don’t often get the same visibility as non-gitanos in the flamenco industry. “The gitano community is a community of specific importance to flamenco — of codifying flamenco. The visibility some of these artists haven’t received — I empathize with that.”

Rosalía has collaborated with a number of gitano artists since the start of her career. Most recently, for El Mal Querer, she recruited the palmero duo Los Mellis de Huelva, percussionists who provide the staccato hand claps on “Pienso en Tu Mirá” and “Di Mi Nombre;” on her North American tour, twin brothers Fran and Nico Santiago-Fernandez are stepping in. She also says that eventually, she’d like to open up a space where she can mentor other artists. “I would like to, with time, if I can, have a space where I can share with everyone who wants to study music. Everything I build and learn in these years, I would love to put it to use for other people, for other artists, for other futures. Because a lot of times, as much as you want it, your environment doesn’t allow it.”

Still, Rosalía remains concerned about the criticism. It’s something she struggles to square with her deep reverence for the flamenco tradition, and she keeps coming back to the labor she has put in. “I understand that in the end, it’s not an attack against me personally, but I also think that someone who attacks in that way maybe doesn’t know the whole story,” she says. “The work, the effort, the path I’ve had to follow, and the respect and love I put in all of this. But at the same time, I understand where they come from, and why.”

Back at the hotel, Rosalía's nails now have so many rhinestones on them that they resemble talons. I feel like Ivy Queen would be proud.

Pili walks over from the other side of the room with her laptop to show me a rough cut of the video for “Aute Cuture.” “Every time I watch it, I like it more,” Pili says, grinning. She helped conceptualize the video, which was directed by Bradley and Pablo, the duo behind Migos, Nicki Minaj, and Cardi B’s “MotorSport.”

True to form, it’s a fantastical ode to femme empowerment, viewed through the lens of nail art. The video opens with a figure in a leather bustier and lime-green boots who uses the spiraling shape of an acrylic extension on their pinky finger as a cigarette holder. “In the business of beauty, things aren’t always pretty,” they say in English. “This was especially true in the affairs of Aute Cuture, a mystic beauty gang. The gang once came over this town doing perfect fucking nails, said to contain uncanny magic.”

After "Aute Cuture" opens a salon in a mostly deserted town, Rosalía — sporting golden claws — clashes with the Green Bros, described in the video as two “nasty business associates” with lime-green hair; following a deal gone wrong, she slashes one of their cheeks with her talon. Rosalía appears fantastically unbothered throughout — and I can imagine the stans writing “Yaaas queen!” in the comments already.

Uncanny magic: That’s the feeling that Rosalía and her sister say they want to convey. More than a decade has passed since they spent their days dreaming up worlds with their Barbies, but when it comes to their creativity, they’re still living deep in their heads, high above the ground. “At the end of the day, what I like in art is creating worlds,” says Pili. “You depart from reality, but create something different. To free yourself, to do whatever you want.”

You can see Pili’s art history degree inscribed all over Rosalía’s baroque videos, right alongside her love of high-end streetwear. Take, for example, the video for “DE AQUÍ NO SALES.” Between shots of a man dousing himself in gasoline and lighting himself on fire, Rosalía sings a cappella in a pool of murky water, wearing a crimson gown and ice-blue contacts. Moments later, she rides a motorcycle down a deserted highway, trailed by a crew of dancers in pickup trucks. The clip for “Con Altura,” her old-school reggaeton collab with J Balvin and El Guincho, takes place on an otherworldly private jet. El Guincho plays the pilot, while Balvin and Rosalía play video games and host a reggaeton rave in the cabin.

The Vila sisters often finish each other’s sentences — Rosalia chiming in here, Pili delivering a thought there. Now, they’re talking about “Malamente,” breaking down the significance of the motorcycle, which doubles as a reference to a bull.

“They’re like visual elements used as metaphors to express what’s behind the song,” Rosalía says. Pili adds: “At the end of the day, the biggest inspiration is the music itself.”

After a bit of back and forth in this vein, Pili looks over at her sister. “Rosalía is a person who knows how to find the best in someone,” she says, lovingly. Then, she hatches a mischievous smile. “She pushes a lot — for the good and the bad.”

“No, for the good,” Rosalía says. “Come on!”

On the night of Rosalía's Red Bull Music Fest show in New York City, palmeros Fran and Nico are lounging on a couch backstage at Webster Hall, chatting with the odd backup singer, dancer, and stage hand. They’ve just changed into matching white tracksuits, a look that at first seems incongruous because in a few hours, they’ll be performing a centuries-old art form on stage. Somehow, it works. All around, women in white bodysuits, translucent tie-front crop tops, and matching pants straighten their hair, WhatsApp friends and family back home, and practice their routines. I hear someone whispering about Rosalía’s invitation to the Met Gala (she didn’t end up being able to make it), and one of her backup singers mutters Bad Bunny’s “Cuando Perriabas” under her breath.

My attempt to be a fly on the wall here doesn’t quite work; after a while, the stage manager turns to me, noticing my silence, and shrugs. “Every dressing room is boring before a concert,” he says, before turning to the twins. “Well, probably not gitano ones.” One brother — either Fran or Nico, I can’t tell the difference — perks up. “It’s like another concert,” he says.

After a while, Pili emerges sporting an oversized, red patent leather trench. She invites me into Rosalía’s dressing room, where the singer’s makeup artist, assistant, and jetlagged mother — who recently arrived from Barcelona — are sitting around on couches, sifting through Rosalía’s luggage. Pili plops down on a sofa, zoning out and scribbling onto a large tablet with her stylus.

SHIE LYU bustier, GYPSY SPORT necklace.

SHIE LYU bustier, GYPSY SPORT necklace.

Rosalía stands up and greets me with a standard Spaniard double-cheek kiss. As she sits down, she requests some ibuprofen, and her makeup artist asks for her opinion on his choice of eyeliner and highlighter.

“This side is a bit longer than the other,” she notes about the eyeliner, looking into the mirror. Soon, they launch into a five-minute back-and-forth about whether the highlighter is hitting the light correctly before deciding to scrap it and go with something else. As she works with her makeup artist to finetune the look, I think about something she told me in the hotel room the day before. “I swear to you, it’s like a need,” she said. “It’s like I always have a clear vision, and I always have to realize it.”

About an hour later, after the dancers, palmeros, and backup singers have finished their empanadas, Rosalía exits the dressing room, and they gather for a group pep talk and circle stretch. El Guincho emerges from another dressing room, as he’s set to go on stage first. As she bends down to touch her toes, Rosalía’s high pony accidentally tumbles into one of her dancer’s faces, and another dancer’s boob almost falls out of her white bodysuit. “Ah, my boob!” They all snicker on cue.

When they’re done stretching, Rosalía launches into a speech, like a high school football coach in a rom-com. “It’s very important that we stay connected onstage,” she says. “We’re very close to the crowd, not like at Coachella.” They all nod approvingly, eyes wide and ears open. “Let’s give it a lot of love.”

GUCCI jacket, SOLACE LONDON dress, GUCCI bow, KENZO shoes, SCOSHA earrings.

GUCCI jacket, SOLACE LONDON dress, GUCCI bow, KENZO shoes, SCOSHA earrings.

From the minute she steps into the spotlight, Rosalía holds the room in her palm. The crowd squeals as she leaps across the stage, every step invoking Janet Jackson and Carmen Amaya in equal measure. (Charm La’Donna, a Los Angeles-based choreographer who’s worked with Madonna and Kendrick Lamar, helped develop the choreography in collaboration with Rosalía’s flamenco baile teacher.) As Rosalía transitions from playing El Guincho’s sampler, to nailing the routine to “Pienso en Tu Mirá,” to singing a spectral a cappella rendition of Los Ángeles’ “Catalina,” she seems to levitate off the ground. During one song, Rosalía’s cabal of dancers envelops her in sheer red cloth, her delicate floreo handwork peeking through the fabric. A fan in the audience shrieks, “¡Mátame ya!” (“Kill me now!).

After the show, still spinning, I stumble back to the dressing room with the intention of returning my press badge, but end up chatting with Pili. She is only half-listening and politely informs me that her sister is meeting Caetano Veloso a mere five feet away from me. She also fails to mention that David Byrne is posted up a couple feet behind him.

As I leave the dressing room, I’m reminded of something Rosalía said to me the day before, when I asked her about where she locates herself in the tradition of flamenco.

“There are artists of all kinds,” she said. “There are artists who are here to remind us where we come from; there are artists who are here to show us where to go, you know?”

Rosalía doesn’t fall firmly in either of these categories. On the one hand, she’s an artist with an undying reverance for tradition; on the other, she’s an artist determined to chart her own path. As such, her work illustrates some of the great predicaments of our increasingly globalized music landscape, especially given her roots in Spain, a country where regional identity reigns supreme. Honoring an age-old style’s roots while also harnessing its potential for evolution is no easy task — and in the broader sense, her story is in some ways just another example of what happens when a local culture goes mainstream and its meaning changes.

We live in an era where art has become a public moral battleground, one that we use to examine some of the most pressing social issues of our time. It’s hard to predict how Rosalía’s relationship to the culture she draws on will evolve, but it’s clear that these past two years have forced her to engage more carefully with her identity as a Spanish artist seeking international fame. As Rosalía’s celebrity grows, one can only hope that she will put as much reflection into this as she does with every other element of her artistic practice — even as she continues to draw inspiration from the world inside her head.

“Honestly, I don’t know what kind of artist I am,” she said to me when getting her nails done. She paused for a beat, reflecting on how to communicate what it feels like to be torn between the past and the future.

“I don’t know what my work will mean in a few years. But I am clear that above all else I am experimental. It’s a necessity for me. I don’t know how to live any other way. I don’t know how to do anything else. There is no alternative.”

Fashion Assistant: Bastien Allen. Hair by Tanya Melendez, makeup by Jeffrey Baum using Pat McGrath Labs and In Fiore Skincare.