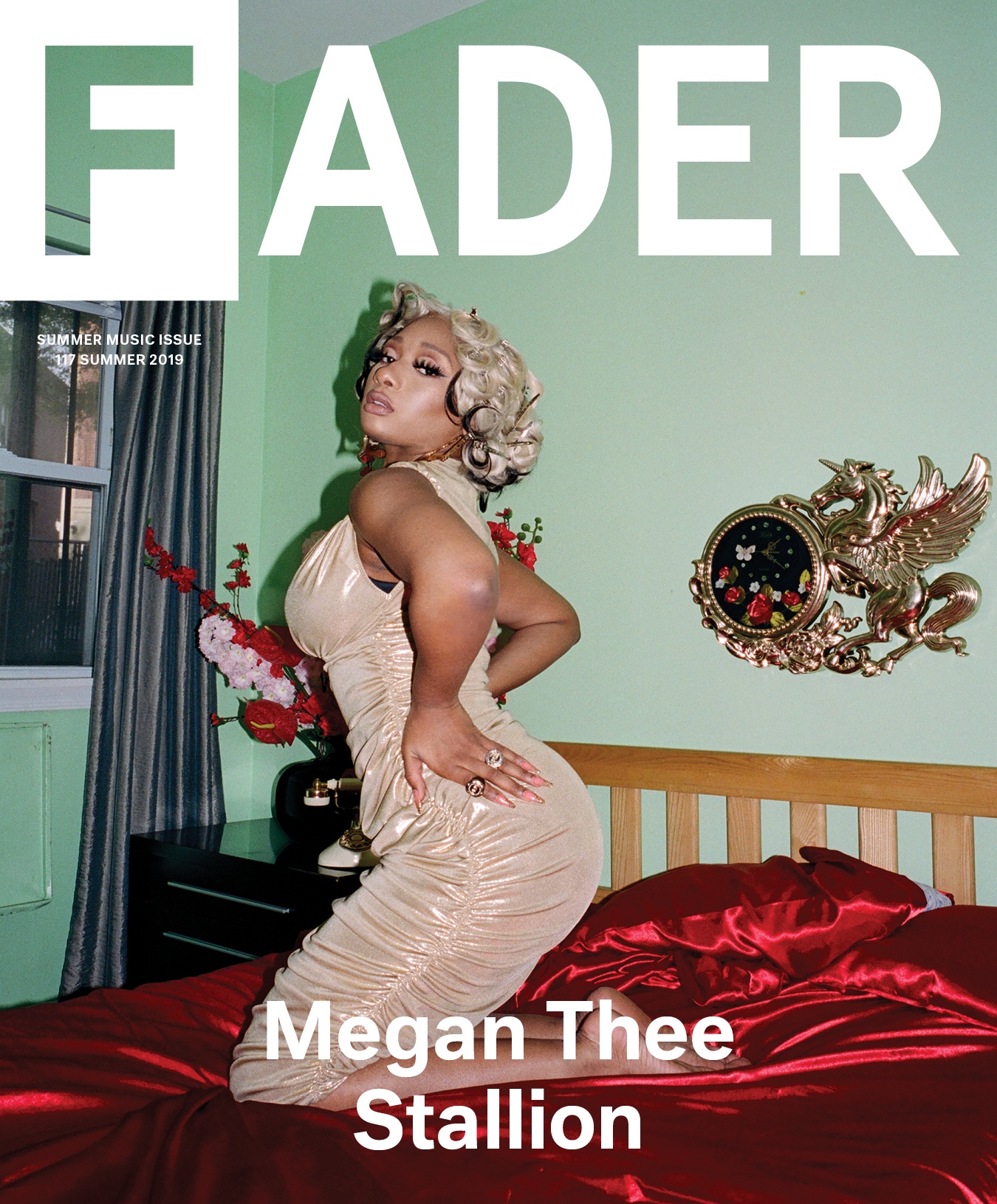

NORMA KAMALI dress, ALEXANDER WANG rings, THE SHINY SQUIRREL earrings.

NORMA KAMALI dress, ALEXANDER WANG rings, THE SHINY SQUIRREL earrings.

Buy a print copy of the Megan Thee Stallion issue of The FADER, and order a poster of her cover here.

A middle-aged security guard with a gravelly voice is looking at me, his gold teeth shimmering in the 90-degree sunshine. “Who are you here to see?” he asks. I’m at the gates of an area in Houston called The Heights — decorated with 10-story homes that could easily double as community centers. The only way this welcome could be more Texan is if he were on a horse. After I answer his question, he presses a button that opens the gate and directs me to my destination: a towering house a few hundred feet around the corner.

Inside, everything — the walls, tables, chairs — is white and gray. The room I’m brought to feels like a coworking space but it carries a weird allure. A platinum plaque for Paul Wall’s 2005 album The Peoples Champ hangs on one wall, another for Mike Jones’ debut Who Is Mike Jones? sits under a desk near the corner, and one more for YFN Lucci’s “Key to the Streets” rests against a different wall. I sit down at a white table, scrolling through Instagram, and then I hear another voice, one that’s just as Texan.

“Hey y’all.”

That voice belongs to Houston’s latest rap star — and one of the hottest new artists in all of hip-hop — Megan Thee Stallion. She stands at about 5’11,” dressed in a cream belly shirt, cerulean sweatpants, and Gucci sandals. At this moment, her hair is bleached blonde with red tips. As I greet her, she’s fumbling through her purse before pulling out a fist full of diamond-filled chains. She clanks them down on the table and tosses an innocent flex: “I’m getting my jewelry cleaned today.” Then she darts up the house’s ridiculously high flight of spiral stairs.

Except for a pair huge silver hoop earrings and a necklace to match, Megan wasn’t wearing much jewelry in her first viral video, November 2017’s “Stalli Freestyle.” In the two-minute clip, she rocked yellow fatigue pants and a black mesh belly shirt, fluidly employing a range of flows about how none of her competition can compare. (The song’s opening line: “You know your bitch is not fuckin’ with Megan / Your nigga not even fuckin’ you naked.”) Since 2016, she’s dropped three mixtapes (Rich Ratchet, Make It Hot, and Tina Snow), each displaying her gift for wielding an impressive toolkit of flow patterns and stylistic approaches to songs.

In 2019, the now 24-year-old is still pulling people in the same way — carrying contagious charisma, the range to step on any beat, and confident, self-assured sex appeal. With her label debut Fever — a 14-track project released on 300 Entertainment — and continued rise of her charting single “Big Ole Freak,” she’s become an internet icon.

Tomorrow night, Megan will perform at Warehouse Live, a Houston venue with a 1,350-person capacity. It’s the first time she will headline her hometown. “These other cities, soon as I walk out, they going crazy like I’m a boy band,” she tells me after returning downstairs. “But Houston people are chill. We can see Beyoncé and be like, Aight cool.” Her giggles imply that she’s equally nervous and excited about the storybook H-Town welcome she’s about to get as Megan Thee Stallion, the star. But Megan’s trek to perceived overnight stardom is one filled with plenty of false starts and recalibration, some of which are still happening today.

NORMA KAMALI top and skirt, LADY GREY necklace and bracelet, MONDO MONDO earrings.

NORMA KAMALI top and skirt, LADY GREY necklace and bracelet, MONDO MONDO earrings.

Megan Pete always knew she wanted to be a rapper. She grew up in a neighborhood called Dead End, part of the larger South Park area of Houston’s southside — home of the legendary Screwed Up Click. Under the leadership of the late DJ Screw, they introduced the world to the smooth, slowed down sound of Houston rap.

“This where the trill is at,” Megan says matter of factly. “We just do real shit on the Southside. Like, we are rich in culture on this side of town. You might see a nigga riding down the street on a horse, pulling up to the light.” She busts out laughing at the thought of that scene.

Megan didn’t have to look that far for artistic inspiration. Her mom was a well-known local rapper for the majority of Megan's childhood, performing under the name Holly-Wood. She grew up regularly hearing her family play the likes of UGK, Three 6 Mafia, and Biggie Smalls. She’d even tag along to studio sessions with her mother.

“Back then, I used to be more quiet, ‘cause I was just observing everything,” she says of her childhood. “And I used to be kind of a cry baby because I was spoiled. I was an only child so, at home, I’m turnt up by myself, doing whatever I wanna do.”

1017 ALYX 9SM jacket, R13 shorts, LADY GREY necklace, THE SHINY SQUIRREL vintage jewelry.

1017 ALYX 9SM jacket, R13 shorts, LADY GREY necklace, THE SHINY SQUIRREL vintage jewelry.

She remembers kids in school being mean to her around that time, too, but says it was her mother who gave her the confidence that’s become her hallmark. “I finally told my mom, and she like, Look Megan, fuck them hoes. They don’t like you ‘cause they hating on you,” she says with a half-cracked smile. “So I went to school the next day — you know when yo’ mama give you the green light, you go all out. Ever since then, I been turnt up.”

Megan got the nickname “Thee Stallion” in high school — stallion being a standard Texas title applied to tall, attractive women — before she ever laid down one bar. That changed when she got to college.

“When you go to college you can just be whoever you wanna be. So I got there and I’m like, Yeah, I’ma rapper,” she says. “One day I was at this party, and these dudes was freestyling and I was like, I could rap, and they was like, No you can’t.” Megan says she dropped a couple bars for them to show off her stuff. “They was like Oh! So then everybody around school knew me as Thee Stallion. And she could rap.”

The towering house in The Heights is known as the 1501 Compound. It’s where Megan recorded the majority of her breakout 2018 mixtape, Tina Snow, and the entirety of Fever. About an hour into me being there, she offers to give me a tour.

We hit the spiral stairs and reach a spacious kitchen on the next floor. “I wish I had more to offer you than some room temperature water,” Megan jokes. “We be ordering food.” When we get to the next floor, where the house’s studio is located, the white and gray color scheme transforms into a vibrant red. Behind the sizeable soundboard in the mixing room is a black table which has a gallon of water, a pair of teal scissors, and a leopard print rolling tray on it. In the hallway, the red walls are almost completely covered with handwritten names of people who’ve come by: Lil Baby, Yella Beezy, Key Glock, rap’s favorite ukuleleist Einer Bankz, and more.

The space — as well as 1501 Certified Entertainment, the local label that calls it home — is run by T. Farris, a tall and burly dude with tattoos covering his arms and hands who’s in the kitchen making calls about the show at Warehouse Live. He got his start as a college-aged A&R at Houston’s Swishahouse Records in the early 2000s, eventually becoming president of the label after he found success helping a young Mike Jones and Paul Wall become two of the country’s hottest rap stars in 2005. It’s that time period — in the buildup and realization of Houston’s last Golden Age — that Megan first found the inspiration for her artistry. Back then, artists like Jones and Wall fed their base with mixtapes that had equal amounts of original tracks and freestyles over already-popular production. That’d probably explain why she’s made freestyles such a crucial pillar of her come up.

As a child, Megan entertained herself by watching her mom’s collection of freestyle DVDs. “I watched those video compilations, so I’m thinking that’s just how it go,” she says, referring to the creative spirit of putting lyrical skill to the test. “So by the time it’s time for me to do it, I’m like This is what I know, and this is what it’s supposed to be.”

Mainstream rap’s recent departure from that model — at times in favor of a more repetitive, lyrically stripped down approach to music — has been disconcerting for Megan. “To see that it changed from something that I love so much to what’s going on right now really blew my mind,” she says. “Like, we not rapping no more?” She also sees a double standard when it comes to who is allowed to veer off the conventional path. “And then being a girl too — they criticize you harder than they criticize men,” she says. “If I was out there making little noises like Uzi and Carti be making, they would not rock with that. And not saying that they don’t be going hard, because we definitely finna turn up to both of them, but if it was a chick, like — no.”

What Megan didn’t realize was that her love for the roots of the genre would eventually come full circle as her career progressed. She says she was sent to a near-heart attack last year when she learned that the late Pimp C’s wife requested to meet her. “To know that I’m recognized by anyone in his family just makes me feel really good because I idolize that man,” she tells me. At the top of 2018, an unnamed person reached out to her via email, claiming to be a fan but also someone “of a higher status.” Initially, she laughed the cryptic emails off and went on about her life. Then, a few weeks later, her mother, who also served as her manager at the time, handed Megan the phone. When she asked who it was, her mother casually replied, “Q-Tip.”

NORMA KAMALI top and skirt, LADY GREY necklace and bracelet, MONDO MONDO earrings.

NORMA KAMALI top and skirt, LADY GREY necklace and bracelet, MONDO MONDO earrings.

“I still haven’t even asked him how he found me,” she says, with palpable disbelief still in her voice. “I went up to New York after that and we were just riding around together, listening to all kind of music, listening to my music, and he’s just giving me so much energy.” Megan and Tip now talk on a regular basis — they touch on everything from their favorite music to career advice.

She tells me about a time, recently, when she got sushi with him in New York, and after the restaurant closed, he started rapping. “This nigga had started rapping inside the sushi place,” she says. “And I’m like, This what they do in New York? Nobody saying nothing? They just eating they food. He very animated, so he’s like going all out, and he’s not a quiet person. I don’t think he know how to whisper.”

In March, Megan posted a short video to Instagram that showed her, her mom, and Q-Tip riding around New York City blasting Max B’s “Movin On Out The Door.” It was justifiably cherished by New Yorkers up and down social feeds, but beyond that, Tip’s presence validated Megan as someone whose skillset was sharp enough to impress the genre’s pioneers.

“She’s just an amazing MC” Q-Tip says of Megan, via an iPhone voice memo sent to The FADER. “She’s barred out. Some people may think her stuff is just over-sexualized, but it is her approach to it. It’s her tact with it. It is very innovative to me — especially to see a young woman like herself being in a position of standing in her power, to stand in her royalty and never let that be shaken. It was just something in her that I really love.” Tip also says that he’s executive producing Fever.

Fever is the kind of album that soundtracks the strip club, the let out, and late-night packed car rides around the city with equal precision. Unlike her last project, where she rapped under her Tina Snow alias, this one summons Hot Girl Meg, the most rowdy of her alter egos.

“Tina Snow is the pimp, the mack,” she says. “She very calm, but she cocky as fuck — slap the shit out yo’ ass. But with the back hand, though. Now Hot Girl Meg, she gon slap you this way,” she continues, demonstrating the much more disrespectful open-handed slap. Fever reflects that energy.

From the beginning of the album, Megan is traveling at full speed like she doesn’t have a second to waste, her voice more commanding than it’s ever been. Fever’s first track, “Realer,” creeps in with pulsating echoey synths similar to Trap or Die-era Shawty Redd before Megan comes in, sonorous and assured: “Say nigga! I don’t wanna talk / Meet me at the bank, show me what you really ‘bout.” From there, she paints scenes of twerking and downing bottles of Henny with friends on songs like “Hood Rat Shit.” The bounce in the Lil Ju-produced “Shake That” feels like the album’s best shot at a club hit. The song hilariously features a line about Megan being so good in bed that she makes a dude hit The Woah.

The album only has two guests. Juicy J — who appears in the credits for three tracks — shows up to slide Billy Paul’s butter smooth 1972 hit “Me and Mrs. Jones” into the twerk instructional “Simon Says.” She and Charlotte, North Carolina breakout star DaBaby — the only other rapper whose rise feels as strong as Megan’s right now — spar on a blaring track properly titled “Cash Shit.” What Fever shows in comparison to Megan’s earlier work is not so much a drastic improvement in her rap skills, but the detectable rise in her voice and delivery suggest that she’s fully aware of how big this moment is. Everything about the album feels grand. And throughout, she’s welcoming the challenge with her arms widely outstretched.

Megan receives a phone call after giving me a tour of the 1501 Compound. It’s time for her to rehearse for tomorrow’s show. “It’s gonna look like a bedroom in a way, but at the same time, we tryna get a mechanical bull,” she says of the set design. “I don’t know if they gon be able to get it, but if they can, we gonna put a bar on stage. Like some Coyote Ugly shit.”

We all head out into the Houston heat, and about 20 minutes later, I pull up at the address I was given for the rehearsal space. It’s inside of a shopping center, which is surrounded by two other shopping complexes. Inside, there’s a French bakery, a child karate center, a gym with a juice bar, and a Domino’s Pizza. I order cheese sticks to munch on before everyone shows up. Megan’s publicist, who’s been with us all day, gets a call from Farris and Megan, who say they’re inside the space that we still can’t find. Eventually, it becomes clear that there’s an entire backside of the shopping center, which is so big that it feels like a completely different one. Houston is supremely American in this way: stitched together by giant marketplaces filled with stores you never thought you needed until they’re in your field of vision.

When we get down to the basement of the space on the complex’s backside, Megan is still in the same fit, except now she’s traded her Gucci sandals for a pair of high-heeled boots. She sits down on the studio floor against the wall-length mirror. Perusing Instagram, she reads us a DM from a girl who thinks she just saw her walk into the studio we’re in. The fan wants to come take a picture, which Megan seems fairly open to, but she quickly forgets once her creative director shows up to assist her on her steps.

The rehearsal is a taste of what’s to come. The DJ puts on Ginuwine’s “Pony,” and Megan’s creative director, Devyne Stephens, guides her movements. “Here, like this, right here,” he instructs, while she prances. When “Big Ole Freak” comes over the speakers, she grabs an imaginary mic, looks in the mirror and stares squarely into her own eyes, lip syncing the lyrics and imagining herself in front of tomorrow’s sold-out crowd.

During a break, I ask if she remembers what her first show ever was like, which she mentions was at a strip club in Austin near SXSW in 2017. “I’m in there, and they don’t know who the hell I am,” she says, laughing. “They see a girl, and I guess they liked what I look like, so they were paying attention. But some people’s mouths were just open, looking at me, like, Whaaat. I did not know you was about to get up here and say this! After the show, everybody was like, What’s your Instagram? What’s your name? It was really crazy — I was so nervous. But now I’m way more comfortable performing.”

“This where the trill is at. We just do real shit on the Southside. You might see a nigga riding down the street on a horse, pulling up to the light.” —Megan Thee Stallion

After working up a sweat, she takes a seat against the wall, sipping on a freshly pressed mango juice. She looks to Selim Bouab, senior VP of A&R at 300, who’s also sitting in on the rehearsal, and expresses her concern for “Big Ole Freak” not yet cracking Billboard’s Hot 100. Bouab tells her that the song came in at 101 that week and not to worry, because it was due to an uptick in streaming of Nipsey Hussle’s music following the rapper’s tragic death a couple weeks prior. She seems relieved.

When Megan isn’t busy being a rap icon in the making, she’s face deep in coursework. She’s currently taking classes online to finish a degree in health administration at Texas Southern University. Her goal is to open a string of assisted living facilities around the city with her rap money, and hire her classmates to run them. She says her motivation to do so stems from seeing her grandmother take care of her great-grandmother at a time of life when both of them should have been able to take it easy.

It took her a few false starts to settle on this plan. Since she first started college in 2013, she’s tried her hand at studying nursing, business management, and biology (“Do you know how many bones is in your body? No you don’t — nobody need to know, it’s too many”), before finally locking down on this one. Even when she’s traveling from state to state for her rap career, she’ll be logged onto her school’s database, finishing assignments — a true test of willpower.

NORMA KAMALI dress, ALEXANDER WANG rings, THE SHINY SQUIRREL earrings, CHLOE GOSSELIN sandals.

NORMA KAMALI dress, ALEXANDER WANG rings, THE SHINY SQUIRREL earrings, CHLOE GOSSELIN sandals.

It’s in these moments — cramming homework, stressing over chart placement, and mastering complex dance steps that might look, to the uninformed outsider, like simple ass-shaking — that Megan Thee Stallion’s rise becomes an obvious sign of her tenacity and discipline rather than a flash in the pan. Hip-hop’s convergence with social media has yielded a myriad of artists who are maestros of immediacy. They prioritize virality, and their ability to generate mass hysteria often arrives so fast that they find themselves ill-equipped to replicate the initial thrill they generate.

As you might expect, these artists often fade away before they are able to build a solid career foundation. Megan Thee Stallion isn’t one of them. Along with artists like Lil Yachty and Rich The Kid, she’s part of a new, entrepreneurial generation that is using internet fame to leverage long term influence and ownership. Her rise might feel like an overnight success story, but that’s far from the truth. In the last three years, she’s worked steadily, releasing four projects while dropping electrifying freestyles in between. When she’s prepping for her radio station freestyles in different states, which have become something of a calling card, she researches particulars of the region so she can draw on her audience’s experiences. She organizes real-life intimate house parties across the country for her fans (The Hotties) to bond with her — all while being a college student putting the pieces in motion for a string of healthcare facilities.

To date, most discussions of Megan’s empowering qualities have centered around her sexual autonomy. But I’d argue that the thing that makes her so relatable is the sense that, like everyone, she’s in a perpetual state of trying, failing, failing some more, adjusting her course, and trying again, without ever having the guarantee of success. Having a secret childhood passion that you finally gain the courage to try in college is ordinary. So is switching through three majors and a couple schools before finally having an ah-hah moment. Megan has been able to galvanize so much support because she reminds people of the part of themselves that’s dedicated to creating the reality they desire most, even if it takes five more tries than they thought it would.

A couple weeks before our interview, Megan faced the biggest test of her young life. Her mother and manager Holly Thomas — who continually pushed her be the best artist and person she could be — died after battling a cancerous brain tumor. She was 47. Two weeks before that, Megan had lost her great-grandmother. Back at the 1501 Compound, just before we left for rehearsals, she brings it up.

“I haven’t been talking about it,” she says to me before taking an extended pause and walking to another room to gather herself. I sit alone at the white table, thinking of a way to swiftly switch the subject when — or if — she returns. Five minutes later, she comes back, sits at the table and clasps her hands together before letting out a deep breath to finally speak.

“My momma wasn’t a weak person and she wasn’t a complainer,” Megan says. “So I don’t wanna be like that.” She seems to be working through her reluctance to speak in real time.

Since her mother’s death, Megan has been on a non-stop grind, performing throughout the country and promoting Fever. “No matter what I’m going through, I still want to keep going,” she continues. “Just to show people you can still be strong and you can still face your everyday life. Even when everything coming down on you. I didn’t cancel none of my shows ‘cause I just knew — I know — how my momma is, and I know she wouldn’t want me to stop.”

“My great-grandmother and my mother passed like in the same two weeks, so I have to be strong for my uncles, my cousins. My other grandmother still alive so, like, I just don’t never even cry in front of them,” she says, noting that, more than anything, even her blossoming career, she feels the weight of keeping her own composure for the sake of her family.

Megan was raised by three generations of matriarchs in South Park. She tells me her great-grandmother was well-respected throughout the neighborhood for being a caring person who looked out for the people around her. It’s clear that she wants to gain the same kind of favor within her community, and Houston as a whole. “Everybody know my Big Momma as Big Momma," she says. "Houston is big, so for somebody to know who my momma is, so many people know who my Big Momma was, that just got to mean something. That gotta mean they was some type of good people. I wanna be that too.”

We sit in silence for a minute.

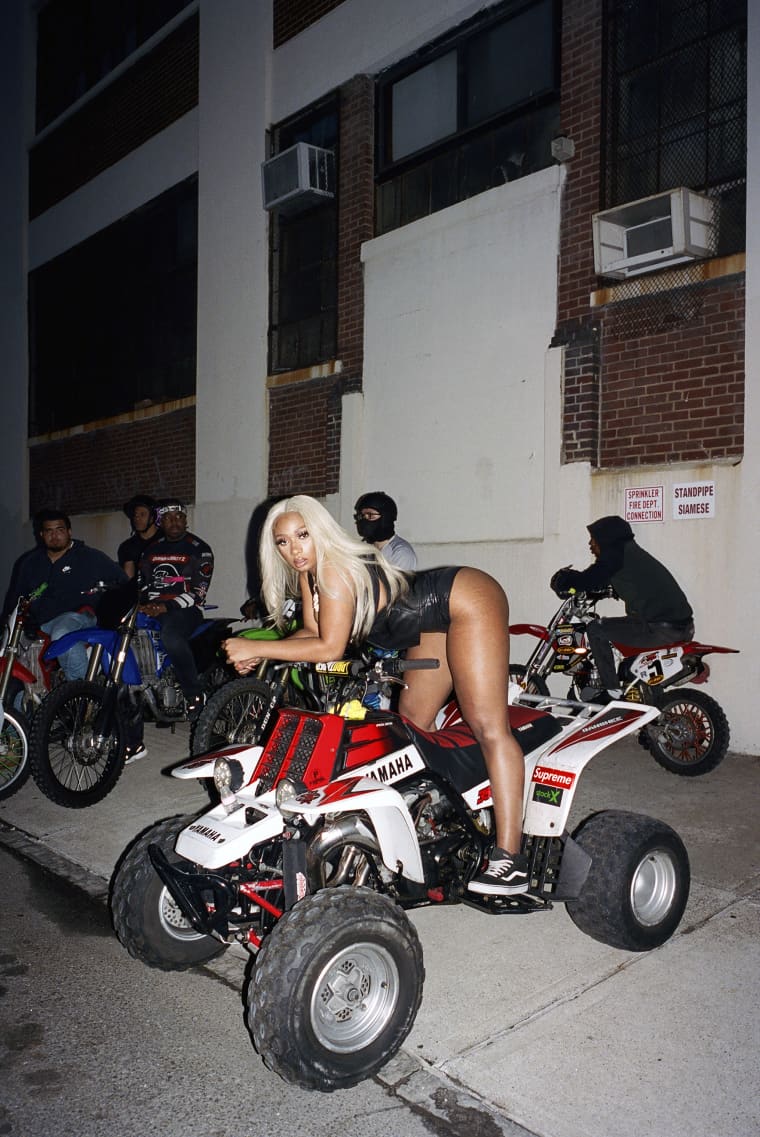

ALEXANDER WANG leather vest, MEGAN'S OWN shorts, shoes, and jewelry.

ALEXANDER WANG leather vest, MEGAN'S OWN shorts, shoes, and jewelry.

The following evening, at Warehouse Live, four hours before showtime, Megan walks into the venue after spending the first half of her day at the salon. Her hair now fiery red, she folds her arms and gazes long and hard at the stage, which ended up being too small for a Coyote Ugly bar and a mechanical bull. Instead, her team created a makeshift bed-like structure next to a stripper pole.

After her appraisal, she turns around and gives me a hug: “Wassup pimp?” Feeling frozen from the venue’s air conditioning, I step outside for a breather and see seven young people who started camping out right after Megan arrived to ensure their entry — they look somewhere between their late teens and early twenties, and two of them are playing Uno on the ground to pass time.

Three hours later, there’s a line wrapped around the corner. Inside the venue, which is illuminated by red lights that hang from the ceiling and stage, there isn’t enough room for people to move around, let alone dance. To prep the crowd for Megan’s turned up, raunchy tunes, the DJ lets off a few New Orleans bounce records I don’t recognize. After about 20 minutes of waiting, Megan slowly and powerfully walks onto the stage, donning a red top and skirt that match her hair perfectly. When she starts grinding to “Pony,” just like she practiced, men and women alike understandably lose their shit.

Megan’s magnetism is clear. She walks back and forth, transitioning from her verse in a 2016 local rooftop cypher to fan favorites like “Tina Montana” and “Big Ole Freak.” Everyone in the crowd screams “HOT GIRL SHIT” with every ounce of might they have when she instructs them to; they get even louder when she gives a light twerk. At one point, I notice a woman just in front of me going toe-to-toe with armed security, arguing for her right to stand on the railing to rap along.

After a good 30 minutes of rapping and dancing, Megan pauses to give herself a breather. On the screen behind her, her black and red logo gives way to a short documentary made earlier this year by this magazine. Over footage of her and her mom walking side-by-side, Megan speaks on the mic about the loss for the first time in public. The weight of not knowing what would come next in her performance transforms the space, which is now completely silent.

Finally, she picks up the mic again. “Y’all know 2019 has been really tough for me,” she says, looking out into the audience. “But I ain’t wanna cancel no shows, because that’s not what my momma would want me to do.” As the audience erupts in supportive claps and cheers, she stops and lets out a chuckle, thinking about what her mother would say if she could see her now: “All that ass shaking and cussing, she’d be like, Twerk harder Megan!”

Fever is out now.