I was three years old when dancehall superstar Buju Banton released his third album 'Til Shiloh and his music became the soundtrack of my childhood in Jamaica. At seven, I remember being puzzled at how the song “Untold Stories” hypnotized every adult to bust out in the reggae-rock-shimmy-dance favored by Caribbean parents after a few glasses of rum. I was 13 when Bruce Golding ran for Prime Minister using Buju’s song “Driver” as his campaign tune, a song about a ganja man trying to escape from the police (Golding won). I was 19 when Buju went to jail in the U.S. for intention to distribute cocaine. And seven years later, on March 16th, I saw Jamaica welcome home a national hero with his first comeback concert, Long Walk To Freedom.

Buju Banton, born Mark Myrie, is more Jamaican than jerk chicken, Red Stripe beer, and a croaking lizard combined. He’s as much a singer as he is a hallmark of Jamaican culture. His lyrics never failed to acknowledge that life wouldn't be easy or glamorous — and it certainly hasn’t been for him. In December 2018, the grammy-winning and genre-defining artist was released after almost seven years in prison in Georgia. Buju went to prison in 2011 after video footage (which was released to the public in May 2018) showed him sampling cocaine in a warehouse full of drugs at the invitation of a man called Alex Johnson. Buju never agreed to a business deal although his friend did. And yet, he was still arrested. Johnson, it turned out, was a paid criminal informant who knocked years off of his own prison sentence and reportedly earned $3.5 million by the time he set Buju up — which earned him $50,000.

The mere rumor that Buju was flying home this past December caused hundreds to rush to the Norman Manley International airport in Kingston, an unusual act for a population that prides itself on appearing unimpressed. On the night of December 7th, the police escorting Buju tried to maintain their composure, but they ended up trying to take selfies when fans began to rush him. Even after the controversy surrounding his song “Boom Bye Bye,” which called for gay people to be shot in the head, some LGBTQ activists were happy to welcome him home. The excitement stretched beyond the shores of Jamaica as well. Diddy posted an Instagram video of Buju boarding the plane with the caption: “Today is a glorious day. BUJU IS FREE. Let’s go!!! King Shit, true greatness.” I teared up as I saw Twitter videos of him deboarding the plane.

Mark Myrie grew up in an impoverished area of West Kingston and began recording at age 12 under the name Gargamel. He rose to fame in Jamaica in the early ‘90s, about a decade after Bob Marley’s death, and cemented dancehall as the country’s new sound. He’s known for his transition from reggae to dancehall to spiritual music. His first two albums Stamina Daddy and Mr. Mention were solidly grounded in dancehall and utilized the saucy lyrics for which Buju became known, like on songs “Batty Rider” and “Love Me Browning.” On the covers of these albums you still see a bald head Buju. The full effect of his shift to Rastafarianism and social consciousness is seen in his 1995 album Til Shiloh which earned him international stardom. Like Marley, Buju’s music is a great social equalizer, appealing to people from all classes and creeds. But Buju encapsulates a part of Jamaican identity that has not been internationally commodified and sanitized the way Bob Marley has, making him feel more relevant. Buju is raw. He is gritty. He is controversial. He is imperfect. He is Jamaica. And for the first time in seven years, the iconic singer had an opportunity to illustrate how much of an integral part of Jamaican identity he still is.

Jamaica in the past 30 years has been like Buju’s career: ever-evolving, contentious and sometimes messy. The country has dissociative identity disorder, simultaneously projecting a pristine image to tourists while also being in the top ten of most murderous places on Earth. Violence escalated in the 1970s when Buju was a child, as the two major political parties encouraged war between their supporters. Politicians corralled their supporters into separate housing schemes — called garrisons — and pumped them full of guns, promising to turn a blind eye to crime and illegalities in exchange for votes. It was in these garrisons that Bob Marley sang reggae and Buju followed afterwards with dancehall. It is an uncomfortable truth that the beauty of Jamaica’s music is a direct reaction to the country’s pain. In 2010, the year before Buju went to jail, Jamaica was in a state of emergency. When Buju landed last December, the country was in another partial state of emergency, in yet another effort to curb the violence, which had now spread into other areas of the island.

Understanding the Long Walk To Freedom concert requires understanding the Buju-mania that overtook the island in the lead up to the concert. After his release, the country’s Minister of Culture, Olivia “Babsy” Grange, issued a welcome during a radio interview, saying, “I look forward to seeing you on stage, welcome home.” But not everyone was happy to welcome him. The Minister of National Security, Horace Chang, said that a criminal did not deserve a “hero’s welcome.” Letters in the Jamaica Gleaner said it was hypocritical to welcome Banton home considering that the murder rate — which rests at about sixth highest in the world — is caused in part by the drug trade. It was contentious as to whether the rasta community would welcome him back, since cocaine — the white man’s drug and embodiment of capitalist oppression — is unforgivable.

But these voices were swallowed up by the overwhelming surge of goodwill. From his touchdown, the collective euphoria was palpable. Everyone wanted to know what Buju was going to do next. Where would be sighted? When was he playing? There was nothing but silence from the Buju camp and the rumors began to swirl, and changed daily. He would perform within the week — no, within the year. Actually, he had a whole album ready to release. A leaked track was said to be his new single, but it turned out to be a song he had been working on before he went to prison. A motorcade escorting DJ Khaled drove through the streets of Kingston where he met with Buju about a “secret project.” Was he being featured on Khaled’s album or the other way around? Everyone held their breath.

Finally at the end of December, Buju’s team announced his first performance, Long Walk to Freedom, a tribute to Nelson Mandela’s autobiography and biopic of the same title. The event was to be held at the National Stadium, which hosted Princess Margaret when she led the ceremony to declare Jamaica's independence from Britain in 1962, Bob Marley’s peace concert in 1978, and Winnie and Nelson Mandela during their visit to the country in 1991. The ticket website crashed within minutes of launching and eventually sold out. But some were displeased with the fanfare. Marcus Garvey scholar Rupert Lewis slammed the ex-con for equating his struggle to Nelson Mandela’s fight to end apartheid. “The appropriation of Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom is unfortunate because what he represented was collective struggle, the struggle of a people, the sacrifice. What Buju represents is more personal freedom,” Lewis was quoted in the Jamaica Gleaner. The counterargument is that Buju’s music is, in fact, about the struggles of poor people. A voice that has been silenced for the past seven years is finally free to lend itself to people who could be served by it.

Much has changed during the seven years Buju was incarcerated. With the internet’s help, the insular island is far more internationally-connected than it ever has been, and the globalization can be seen in the development of the music. The new reigning dancehall king Vybz Kartel, who rose to fame for his slack lyrics and undeniably genius flow during the early 2000s, continues to be musically impactful even while serving a life sentence in prison for murder. Kartel’s protege Popcaan, who recently signed to Drake’s label OVO, has been experimenting with the limits of dancehall. Female artists like Spice and Sheensea have taken over, while Lady Saw, dancehall’s reigning queen of the 1990s, became a Christian minister in 2015. A well-chronicled reggae revival has blossomed as well, headed by Chronixx, Protoje, and newcomer Koffee.

These are artists who grew up listening to Buju and their work is likely influenced by his music, directly or indirectly. Wayne Marshall, who opened Long Walk To Freedom, told me he grew up on Buju’s music as a teenager in the ‘90s. “His evolution from dancehall to reggae to spiritual really inspired me,” he said while wiping the performance’s sweat from his forehead. “He’s Legendary status. That’s why we embrace him as a son of the island and an icon, no matter what. No story, no glory.” That is a common praise of Buju, that he had the talent and tenacity to develop into different genres, bringing us along on the journey. Had Buju not been incarcerated, maybe music’s playing field would look different. But perhaps it wouldn’t — the era of Buju was on the decline before he was even incarcerated, as his songs became increasingly more reggae while dancehall exploded.

The night before Buju’s concert, the festive feeling in the air began to wear and the cracks of real, imperfect life began to show. Buju’s son Markus Myrie, a dancehall producer, released several videos on Instagram blasting his father. “So much drama since December. This man needs to go back to prison and dead in deh,” he wrote. “And you know you fucked up when you come from prison and out of your 17 children not even 10 was genuinely happy that ‘Daddy’ is back. Great ‘artiste’ yeah but write me off a your list pusssy.” Buju’s son ended the rant by calling Buju a coke head. Then he filed a police report alleging that Buju had physically assaulted him.

The very next day, 35,000 of Buju’s fans from across the globe poured into Kingston. The road from the airport came to a standstill. It was like Christmas morning; you could feel the excitement tinged with nervousness. People defied their ingrained Jamaican tardiness and trekked to the National Stadium early to secure their spots. As the crowd trickled in, a cloud of ganja smoke formed above the stadium and hung there for the rest of the night. People wore redemptive white, accessorised with rasta-colored flares. The demonic sound of the vuvuzela punctuated the slow reggae rock that everyone absentmindedly swayed too. People bought their Buju t-shirts and stocked up on mannish water goat soup in preparation for the show.

Backstage was a zoo; it seemed everyone had managed to get a pass for a friend of a friend. DJ Khaled hung around somewhere back there, allegedly along with Rihanna. The rest of the venue was divided into four sections. The bleachers, which cost $35 US. General tickets costing $100 US. Towards the front was VIP at $220. In the VVIP were tickets costing $500, housing most of the country’s pale elite.

Half the crowd or more had flown in especially for the event. Television personality Miss Kitty put it, “Foreign empty, Florida empty, England Empty. Yard full tonight.” To my left, a girl texted her man, who told her that he was sleeping with other women to repay her for sleeping with someone else. To my right was a man with a spliff the size of my forehead. In front of me stood a 6-foot woman with a mane of Ariel-red hair yelling, ”That’s my Zaddy!” whenever the MC called Buju’s name. Another fan summed up his love for Buju by saying, “Buju has always maintained militancy and authenticity. Otherwise we would have said he’s a cokehead and not come.” The moment had the heaviness of a pivotal moment in history. As I looked around I wondered if this is what people felt like watching Bob Marley’s peace concert.

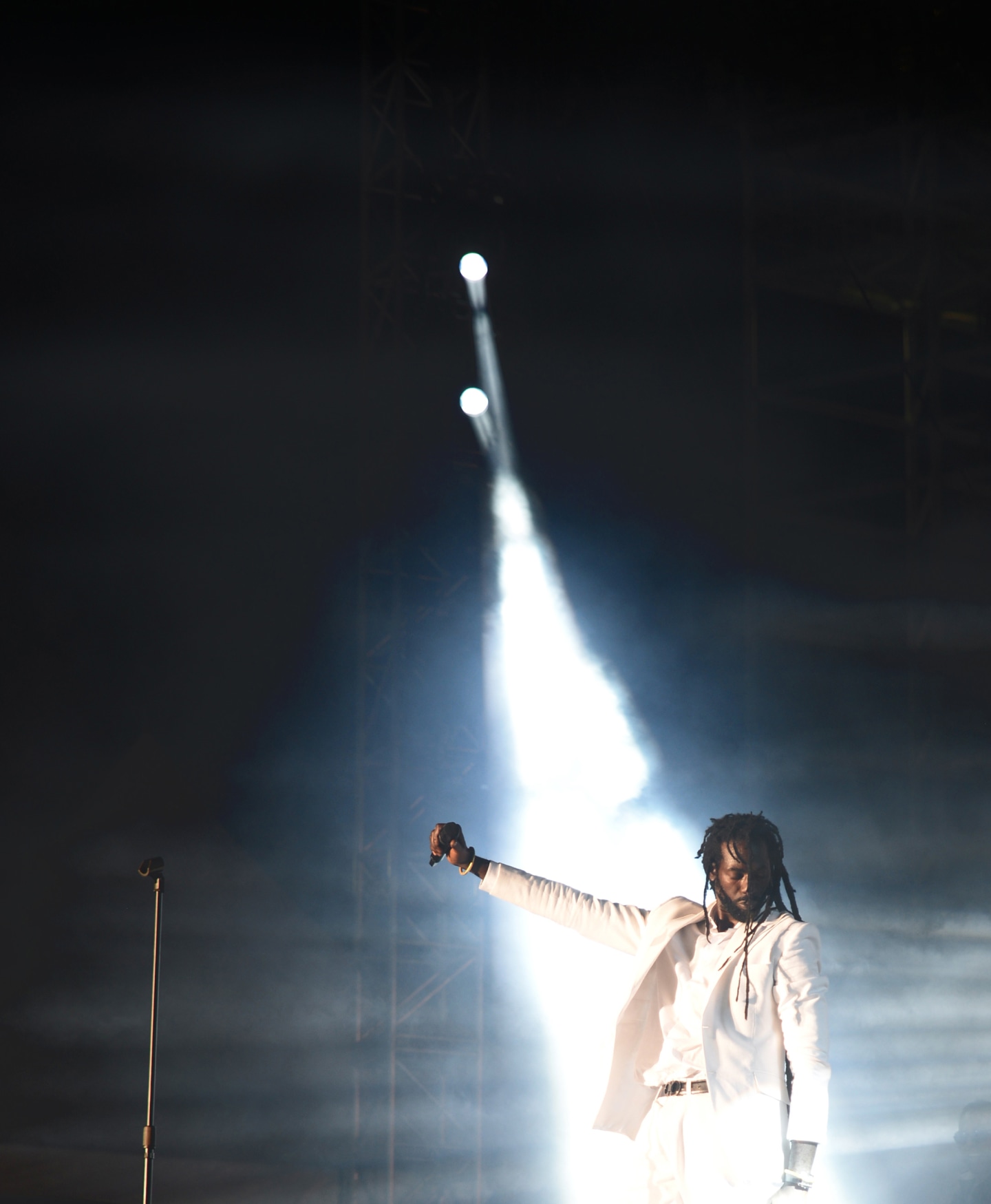

Buju came out in a full white suit, an outfit befitting of a returning messiah. He walked to the standing mic with the swagger of a religious figure ready to conduct his sermon. He started with a prayer “Oh Lamb of God have mercy on me,” and dropped to his knees. There he sat, an older and greyer Buju, with a bald spot and his thinning locks reaching almost his knees. For a moment it felt like there was perhaps a new Buju, one who would put his ego aside and use the show as an opportunity to apologize for his wrongs. That was what some, like the Minister of Health, Christopher Tufton, had hoped he would do: use this moment to preach against drugs and violence, and set an example for Jamaican youth. If there was anyone that people in the crime-riddled country would listen to, it would be Buju. But if someone was waiting for a direct apology, this was not the event for it. Buju’s main message about jail, while he was on stage, was to let everyone know that his rectum was still intact.

His first song selection was “Not An Easy Road.” The entire stadium burst into the parents’ post-three-rums-reggae-shuffle. Buju did the classic rasta man’s high knee running-on-the-spot move. Our boy was home.

By the second song I started to feel a little uncertain, and by the third song I was sure that something was off. There was something slightly incoherent about Buju’s movements, a deadness in his eyes. Some songs he barely sang along to, holding the mic out to let the audience finish it. Had he forgotten the words? Were family troubles on his mind?

The Buju classics were still the classics, and their sincerity still slaps you in your chest. But he felt disjointed and lacking in energy. The most redemptive songs were the duets sung with guest stars like reggae legends Beres Hammond and Marcia Griffiths, who carried most of the weight for him. About the fourth song in, the mic failed. It felt like a cruel joke that Buju would spend seven years in prison for his mic to fail on him at his chance for restitution. The faltering mic felt like a metaphor for Buju’s current situation: trying his hardest but just not quite delivering. My heart felt heavy. I’d wondered if we expected too much of him in such a short amount of time.

I refreshed Twitter to see if anything was being said. Everything was positive. The criticism was mainly directed at one good samaritan who was live streaming the concert from his phone but not getting the angles people desired. It seemed no one was going to publicly criticize the great Buju Banton, not after all the hype, not after what he had been through and what he represented to us. But maybe those I saw on Twitter and social media where the ones with the VIP and VVIP tickets that were close enough to the front that they weren’t affected by sound issues and tv issues felt in general and bleachers. Around me I saw several people only start dancing when their snapchats were recording. By the time I left the concert I felt a deep sadness — for what Buju had been through, and for what I suspect he might put himself through in the coming months while touring. The classical hero arc is much more appealing than the challenges of having to deal with life after incarceration.

While the weight of an entire nation has been plopped onto Buju's shoulders these past few months, it's understandable that he may not be spiritually or mentally ready for that type of pressure. Buju Banton is a musical icon, but his humanity needs to be considered over everything else right now. With any luck, the missteps made during the Long Walk to Freedom opening show were just rust needing to be shaken off. Buju’s status as a cultural legend is untouchable but his place in today’s Jamaica is still uncertain. As he continues to heal and transition back into normal life, hopefully Buju can become a force in this turning point in Jamaica’s music, and in the country itself. Because we need him. No one in the past 25 years has been able to lend themselves to so many of the island's realities with his level of precision. And the road he’s taking to regain internal freedom won’t be one without hurdles to clear.