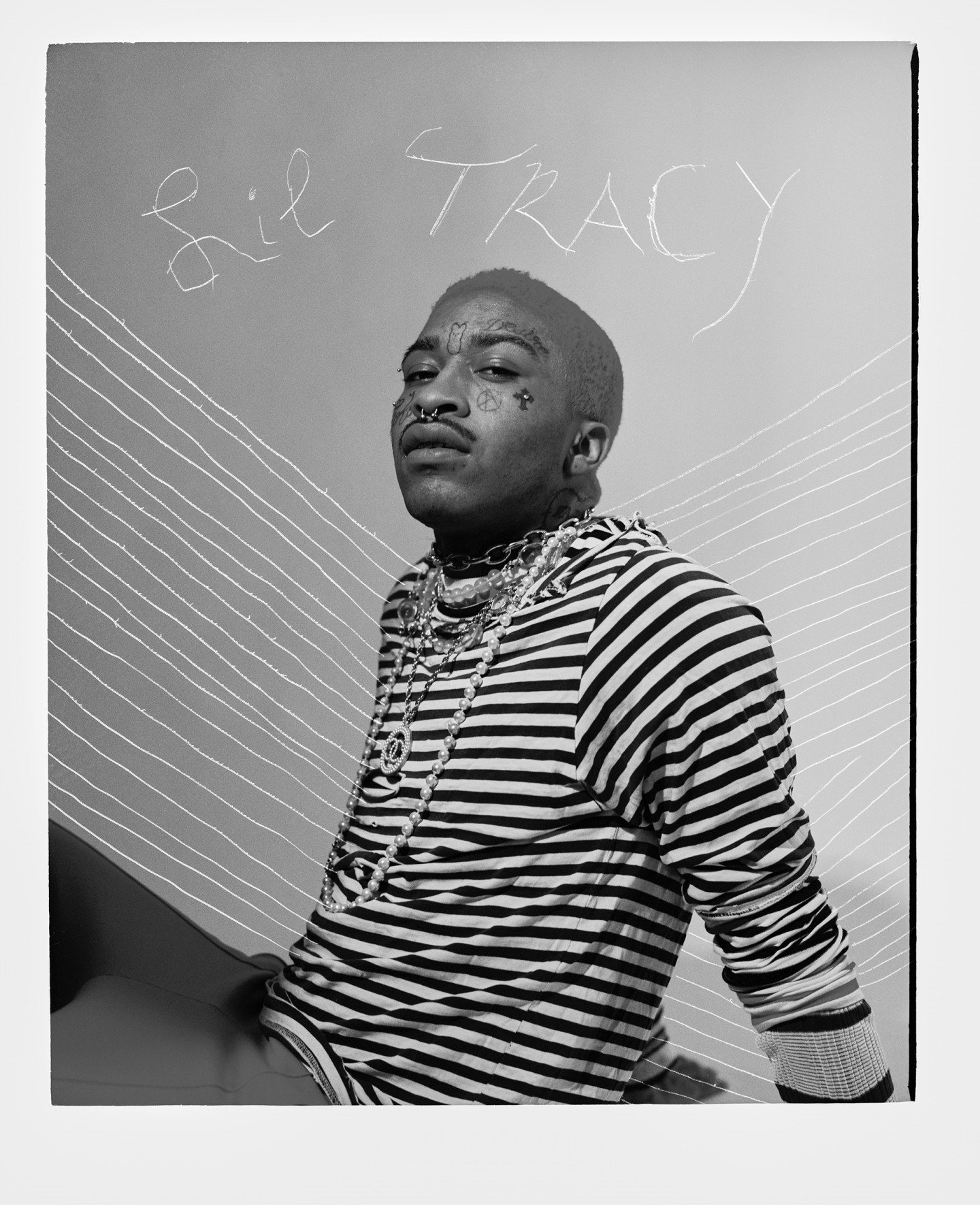

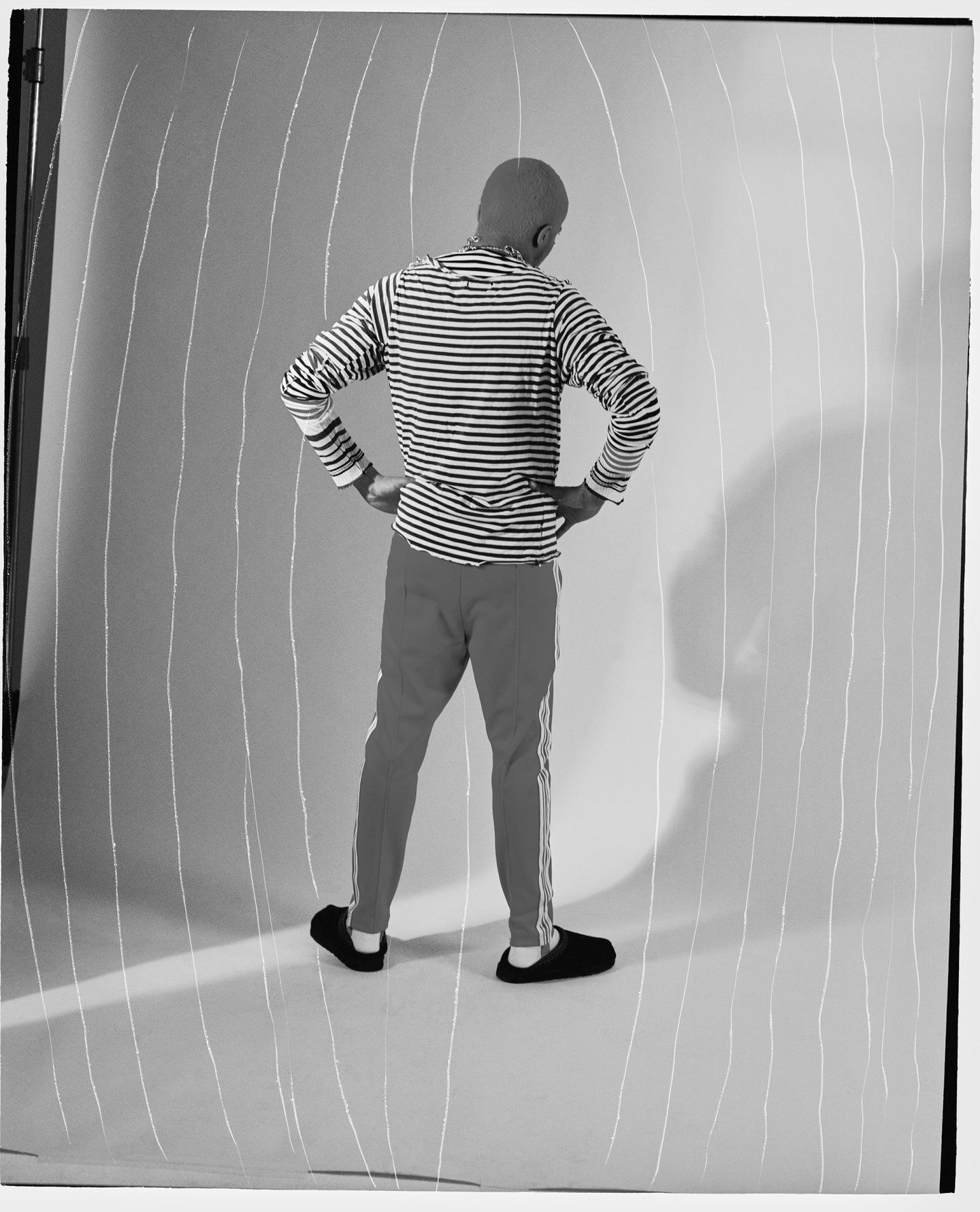

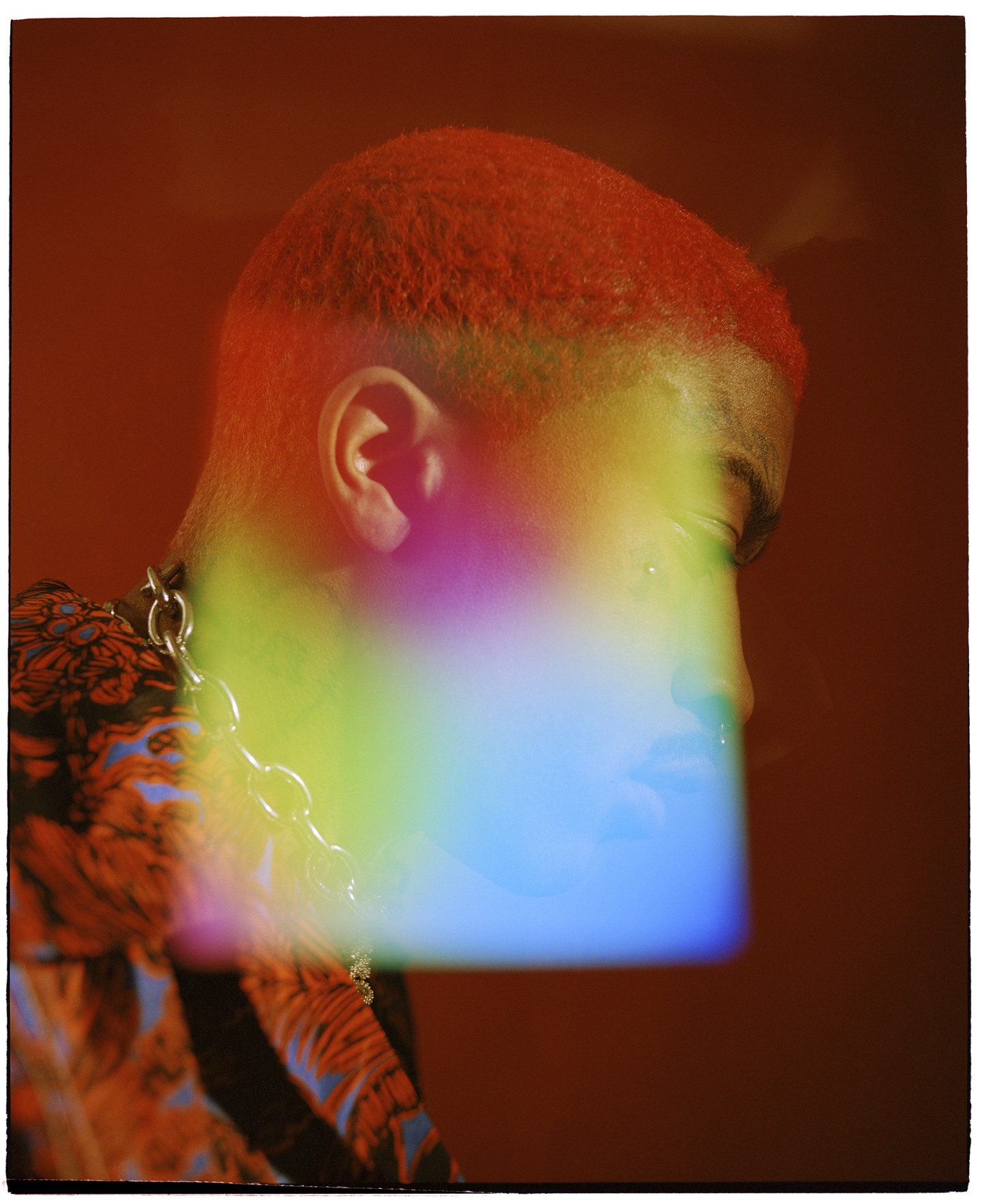

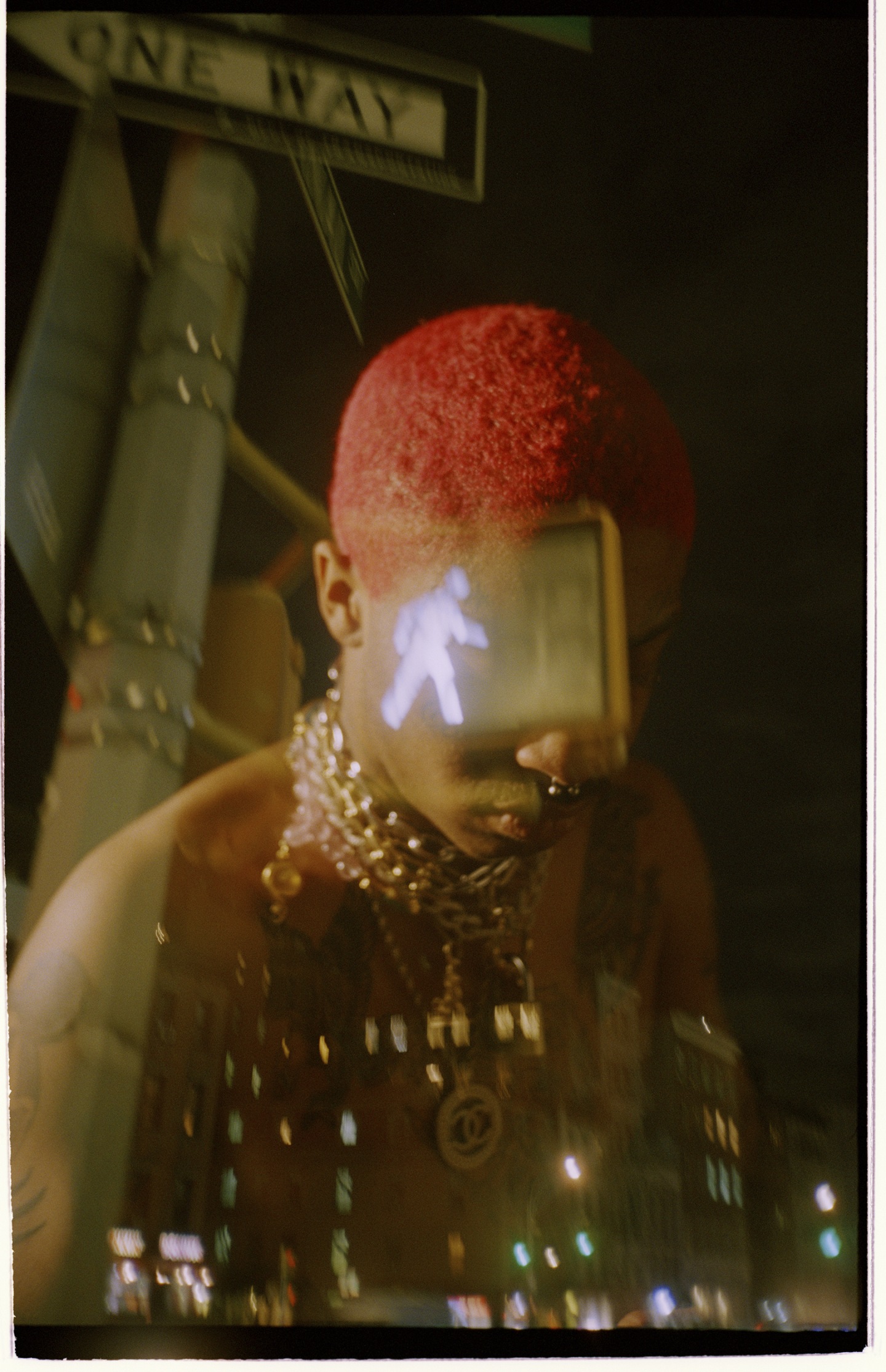

COMME DES GARÇONS PLAY shirt, KENZO shirt, STYLIST'S OWN shirt, JENNIFER FISHER choker, TRACY'S OWN necklaces.

COMME DES GARÇONS PLAY shirt, KENZO shirt, STYLIST'S OWN shirt, JENNIFER FISHER choker, TRACY'S OWN necklaces.

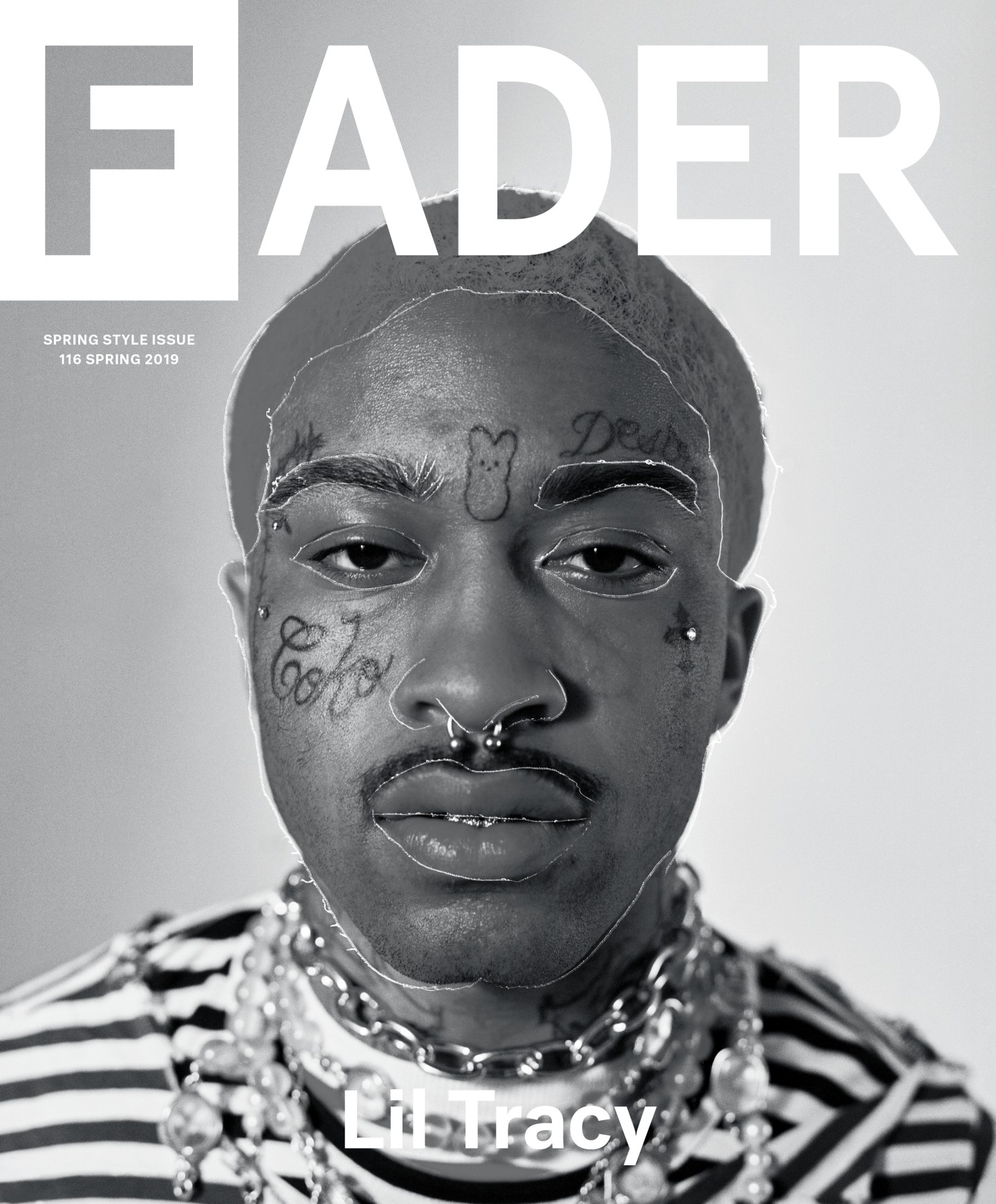

Buy a print copy of the Lil Tracy issue of The FADER, and order a poster of his cover here.

Lil Tracy presses a button and his pants vanish. He’s rocking a trench coat, boots, and pixelated genitalia as he runs into the street, hops on the windshield of a police car, and thrusts his hips forward. Cops jump out and tase him. He falls to the ground, twitching. A bikini-clad stripper lights up the cops with an Uzi until their blood pools on the concrete.

“I probably shouldn’t have been playing this shit as a kid,” the 23-year-old says, grinning.

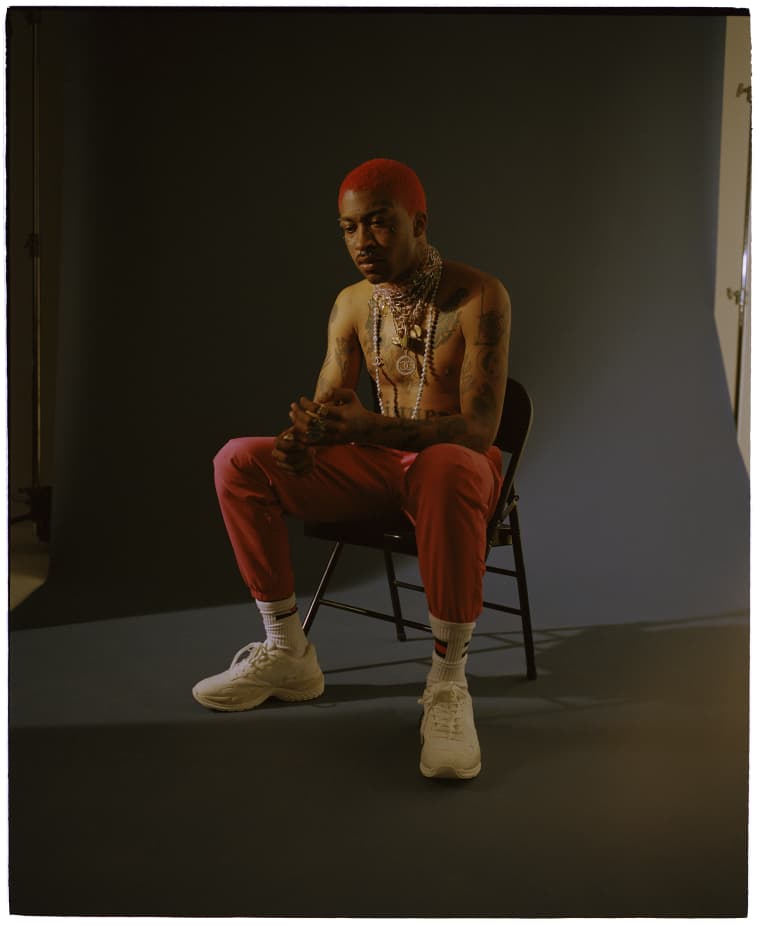

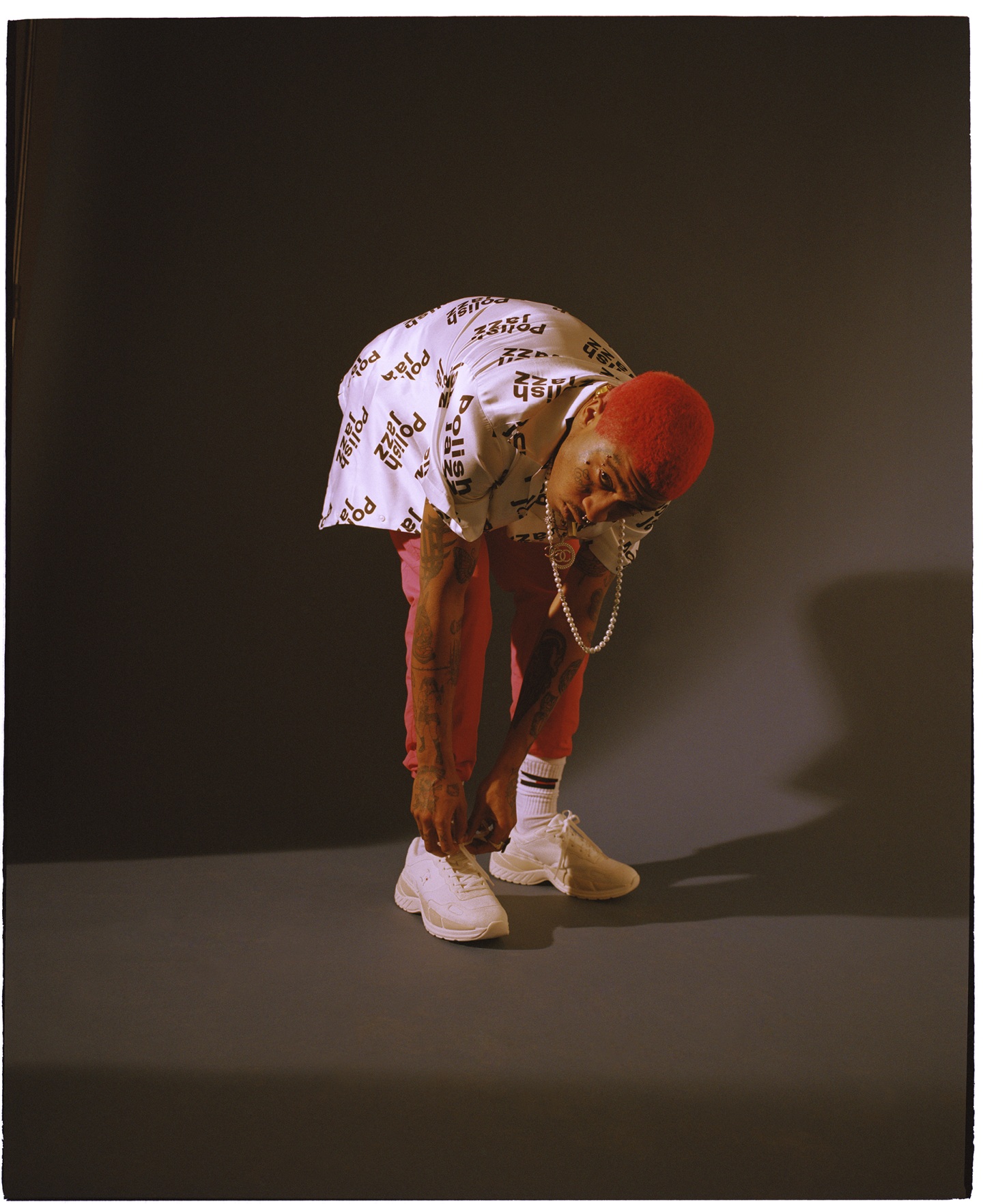

The pink-haired rapper and I are sitting on the floor in the spacious Bushwick apartment he shares with his cousin, the rapper Buku Bandz. Their living room contains a couch, a TV, a PS4, and not much else. Tracy’s showing me his favorite video game: Saints Row 2, a deranged Grand Theft Auto clone from 2008 that promised on its release to “bring open world thug-driven action to the PS3.” As a teen, Tracy spent many hours creating different avatars in the game. “I made a character with a cheat where if they killed you, you would fly into the sky,” he says. “He had a cane. He was black, but really pale, and really evil.”

There’s nothing on the walls of Tracy’s bedroom, but the floor is a map of his mind. I spy a cowboy hat embroidered with skulls, a Chanel pearl necklace, several cute stuffed animals, a ghoulish white mask, and a pile of boxes of high-end clothes and jewelry with a value Tracy estimates at $15,000. His love for character design lives on.

Tracy spent his youth in Virginia Beach, where he ran away from home as a teenager and slept in a tent in the forest (more on that later) before moving to Los Angeles, where he bounced between friends’ living rooms and cars. During that time he’s released music under multiple aliases including Souljahwitch, Yung Bruh, Eblis The Persian Dolphin, and Yunng Karma. Tracy’s varied body of work reflects his renegade lifestyle, motivated by an insatiable desire for freedom — whatever the cost.

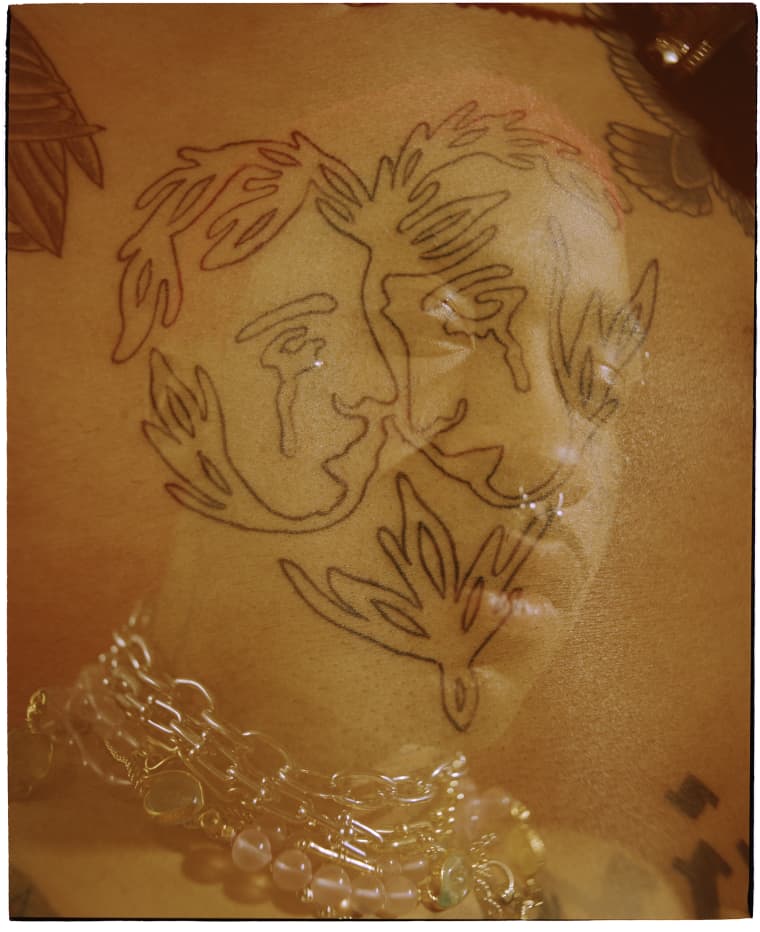

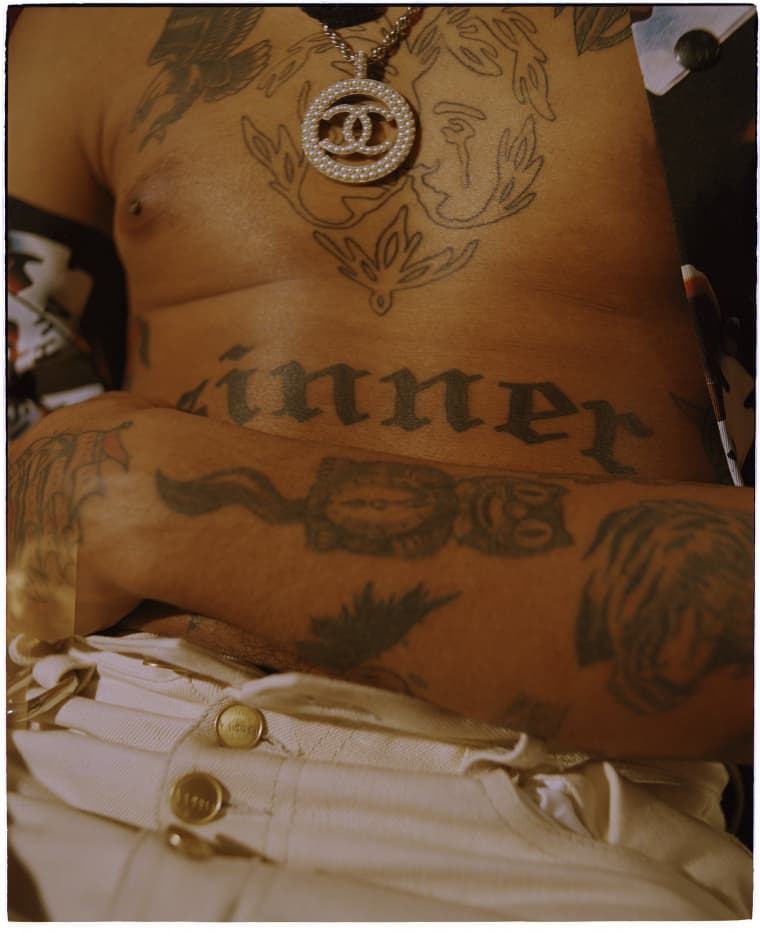

The musician recorded his most recent project — the Sinner EP, released in November 2018 — in the same bedroom room we’re sitting in. The EP is a significant return to the emo-influenced style that helped propel him, alongside Lil Peep and the Gothboiclique crew, to cult hero status in 2016. He wrote the project’s gorgeous single “Heart” last summer, shortly after experiencing a near-fatal heart attack. The song’s cover art — a heart with a band-aid listening to an iPod — reflects his belief that “music is what’s gonna help me get better.” It’s a tribute to a year he barely survived.

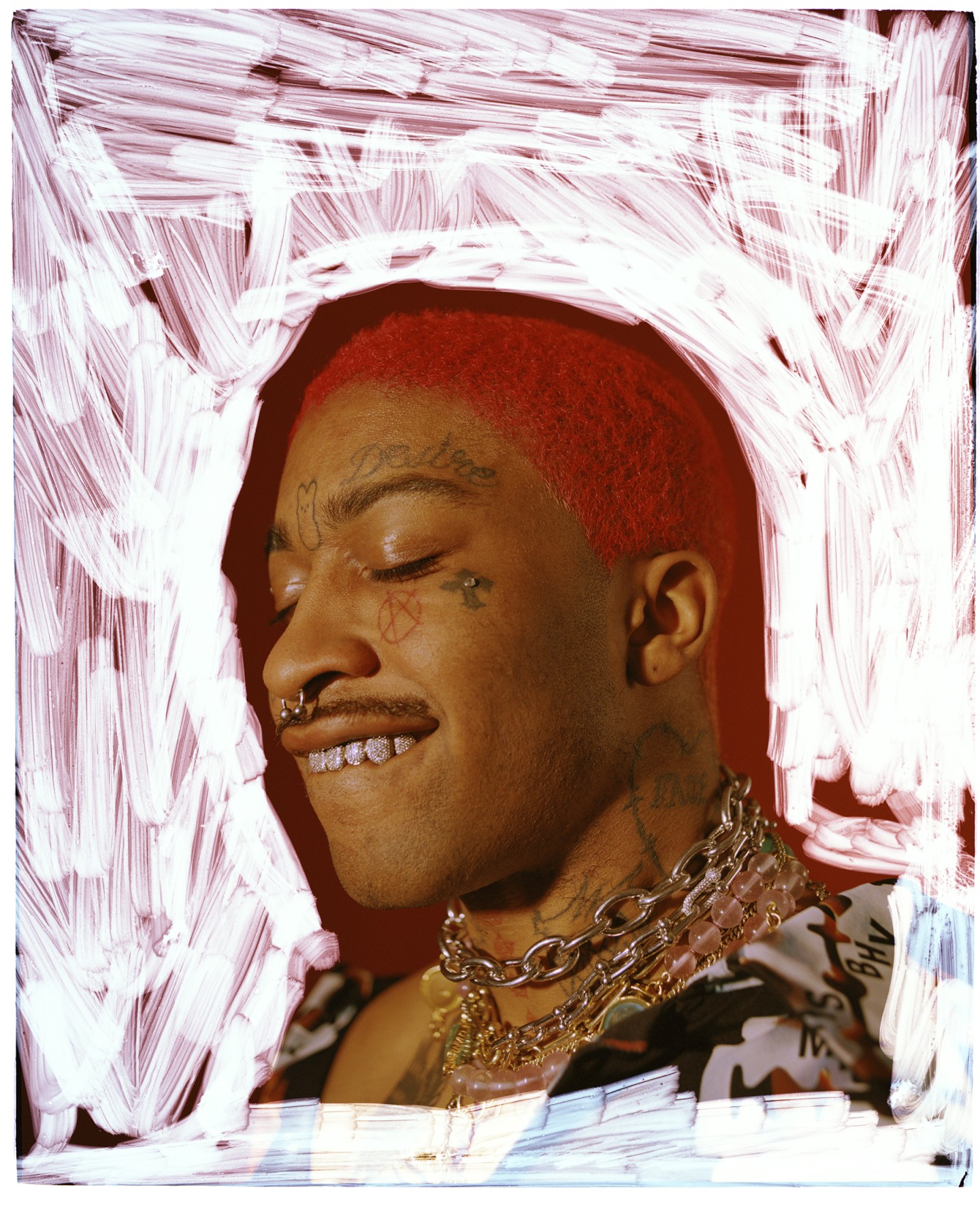

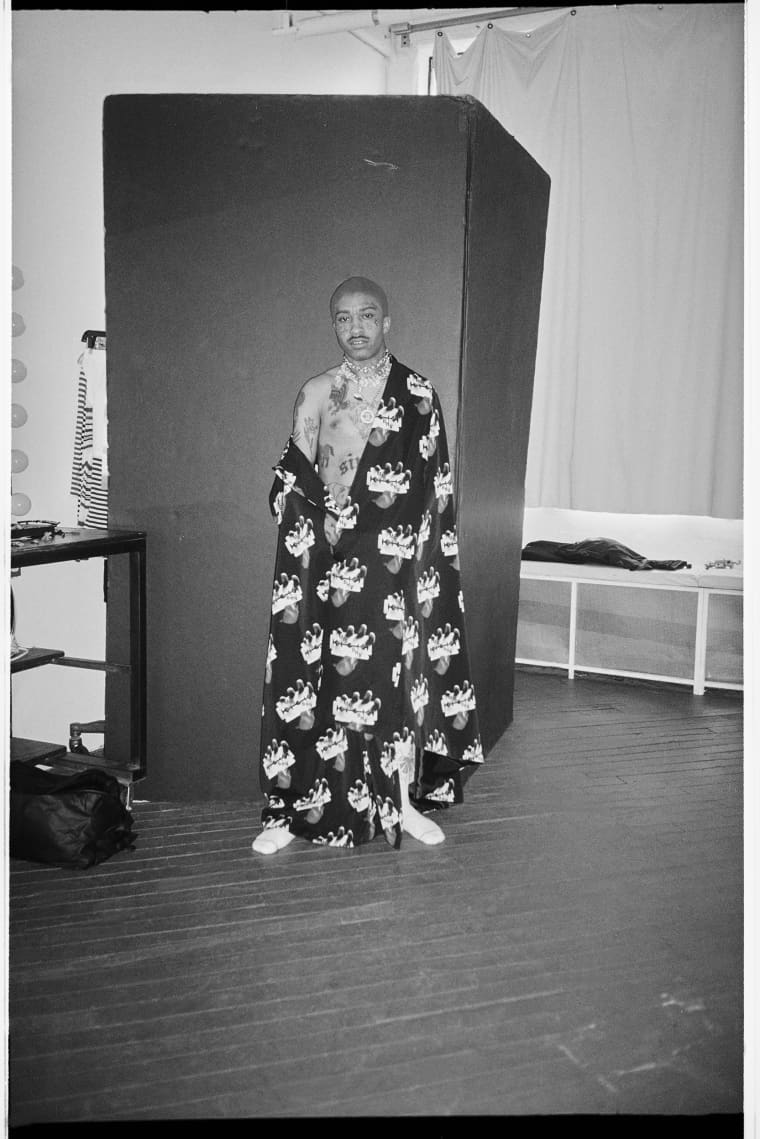

Right most look: MISBHV cape, LINDER pants, 3.1 PHILLIP LIM shoes.

Right most look: MISBHV cape, LINDER pants, 3.1 PHILLIP LIM shoes.

Lil Tracy was born Jazz Butler in Teaneck, New Jersey, in 1995, the son of hip-hop and R&B royalty. His father is Ishmael Butler, who rapped as Butterfly in the trio Digable Planets and Palaceer Lazaro in the duo Shabazz Palaces. His mother is Cheryl “Coko” Clemons of the god-tier ‘90s R&B group SWV. His musical education began early. “He’d be on tour buses with me all over the world,” his mother says. When he was three, she dedicated her solo single “Sunshine” to her son, “because he’s my special guy.”

Tracy’s parents separated when he was very young, and he stayed with his mom. When he was eight years old, she remarried and moved the family to Virginia Beach, where Tracy loved skating through suburbia’s wide open spaces. He hated school, and eventually discovered punk music courtesy of the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater soundtrack. “It changed my life,” he says, citing bands like South Central Riot Squad and The Pins.

Like a true punk, high school was a non-starter. Tracy was expelled his first week of freshman year when a knife fell out of his backpack in class, leading him to an alternative school for troubled kids where teachers didn’t assign homework and the cafeteria was an open air drug marketplace. Tracy stopped going, he remembers, appearing only to buy psychedelics and eat breakfast. Around that time, Tracy discovered Tumblr. He used the name Souljahwitch, and posted about witch house, lo-fi internet rap, and “kawaii goth” tropes. “I used to listen to Balam Acab on acid,” he says.

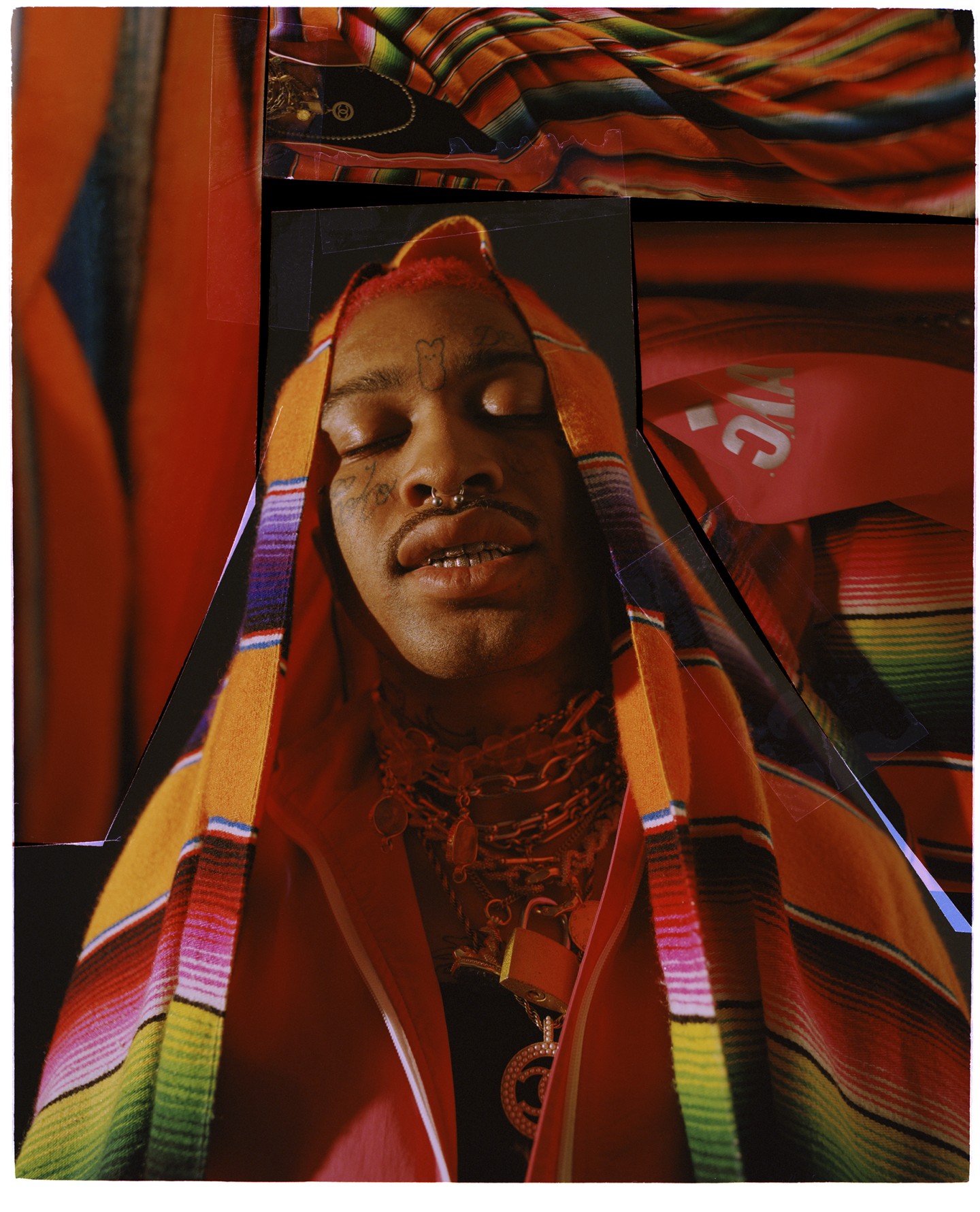

STYLIST'S OWN blanket, KENZO shoes. Overlay: MISBHV cape, 3.1 PHILLIP LIM shoes.

STYLIST'S OWN blanket, KENZO shoes. Overlay: MISBHV cape, 3.1 PHILLIP LIM shoes.

Tracy tells me all of this while sprawled out on his mattress, which is obviously on the floor. The winter sun sets beyond the Venetian blinds of his bedroom window, framing his face in horizontal bars of golden light. He speaks in a soft register without obvious regional signifiers: there’s a touch of Mid-Atlantic drawl, and notes of SoCal skater nonchalance. In another world, he could narrate a nature documentary. Instead, he explains his self-inflicted homelessness during his teenage years; at age 16, tired of fighting with his mom, Tracy ran away from home, stole a tent, and moved into a nearby forest with three friends. His infinite free time was matched only by his total lack of funds. “There was this fountain in downtown [Virginia Beach] where people would throw change,” he says. “I literally would go into the fountain just to get the money and go to McDonald’s.”

Tracy’s homelessness was a time of rebellion that would make Bam Margera proud, and one he remembers with fondness. “Me and my friends were crazy,” he says. “The shit we did, shit we talked about, I feel like that’s what really made me who I am.” It was during this period that music became Tracy’s primary motivation. He’d spend all day recording on his laptop at McDonald’s or at friends’ houses and released a torrent of captivating, lo-fi material under the alias Yung Bruh.

In 2014, he received a message from the LA-based producer Nedarb Nagrom, who urged Tracy to move to Los Angeles. At the time, Nedarb belonged to a loose collective called Thraxxhouse (in reference to Lil B’s term “thraxx”), started in Seattle a few years earlier by the rapper Mackned. Tracy, then 18 years old, ended up crashing on a ragged futon in the living room of a Boyle Heights house where a contingent of the group were living. Artists hung out, took drugs, and recorded music all day; he fit right in. “I felt like I was powering up,” Tracy remembers. One day, Nedarb was throwing away old clothes, and asked if he wanted his Tracy McGrady jersey. He started wearing the shirt and calling himself Lil Tracy. It stuck.

The video for “White Tee,” Tracy’s first collaboration with Lil Peep, opens with a yellow Toyota truck pulling into a nondescript suburban driveway. Tree branches brush the car’s roof as it stops next to a white picket fence. Peep jumps out of the front seat and spits on the ground, followed by Tracy stumbling out of the back door. The camera flits around them as they dance lazily and mouth along to their verses. Sunlight cuts through the leaves, enveloping the boys in smudged halos of lens flare.

Tracy and Peep first met in 2016. They were introduced by Nedarb, who invited Tracy to Peep’s house in Pasadena. Within Tracy’s first five minutes there, Peep told him he had a verse open for him on a song called “White Tee.” They recorded the song and video that day, and the latter quickly hit a million views. “That was probably the happiest I had been in a long time,” Tracy remembers. Peep told him, “Bro, we’re gonna change the world.”

Around that time, Thraxxhouse had dozens of members and confused branding. Adam McIlwee — formerly of beloved emo band Tigers Jaw, who’d created his gothic rap solo project Wicca Phase Springs Eternal under the influence of witch house acts like Salem and Crim3s — wanted to start a new group specifically focused on dark themes. Wicca connected with fellow Thraxxhouse member Cold Hart on Tumblr. “He had sent me a beat called ‘Gothboiclique,’” Wicca recalls. “I was like, that’s what we should call it.” Gothboiclique combined the scrappy DIY approach of Thraxxhouse with a more sharply defined aesthetic. Tracy soon joined the fledgling crew. Cold Hart, now one of his closest friends, remembers, “We were the punks of the scene.”

Initially, Tracy’s ascent moved steadily. He and Peep released a series of collaborations that blew up online. But after a while, he felt like power dynamics between them began to destabilize their mission. Tracy heard through the grapevine that Peep’s management referred to him as a “jackal” who was “leeching” off their star. He also chafed at the way blogs and fans would post about their collaborations without mentioning him. “I felt like race had something to do with it, and the type of music we were doing,” he says.

To understand what he’s getting at, it’s important to think about the context in which Gothboiclique emerged. In the early ‘10s, a wave of artists inspired by ‘90s Memphis rap tapes released music full of references to suicide, murder, hard drugs, and the occult.

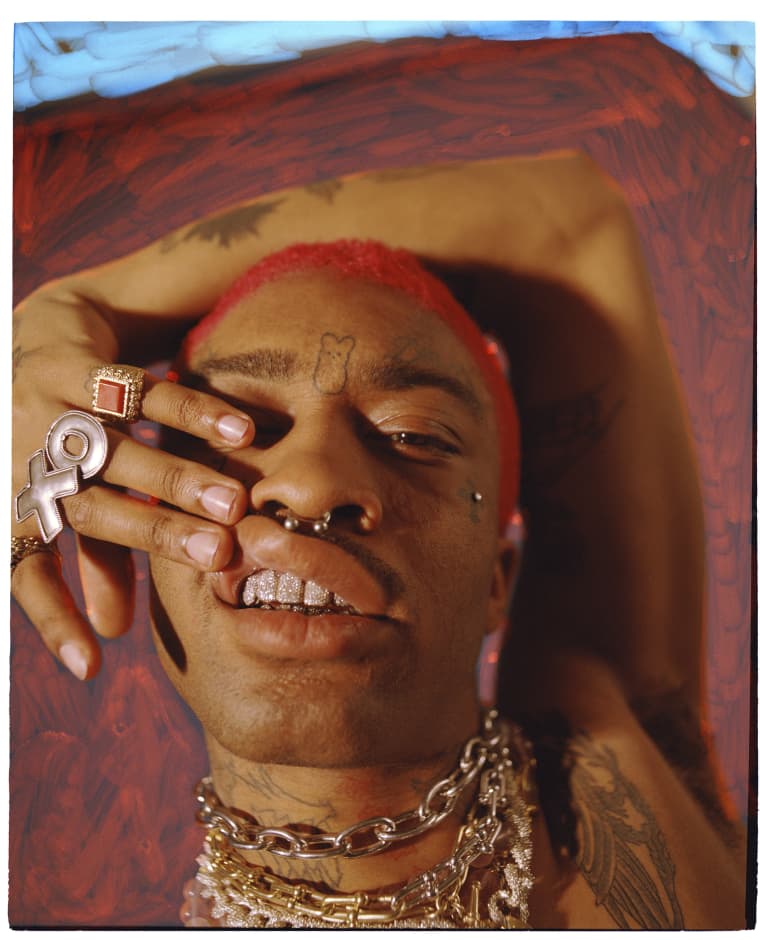

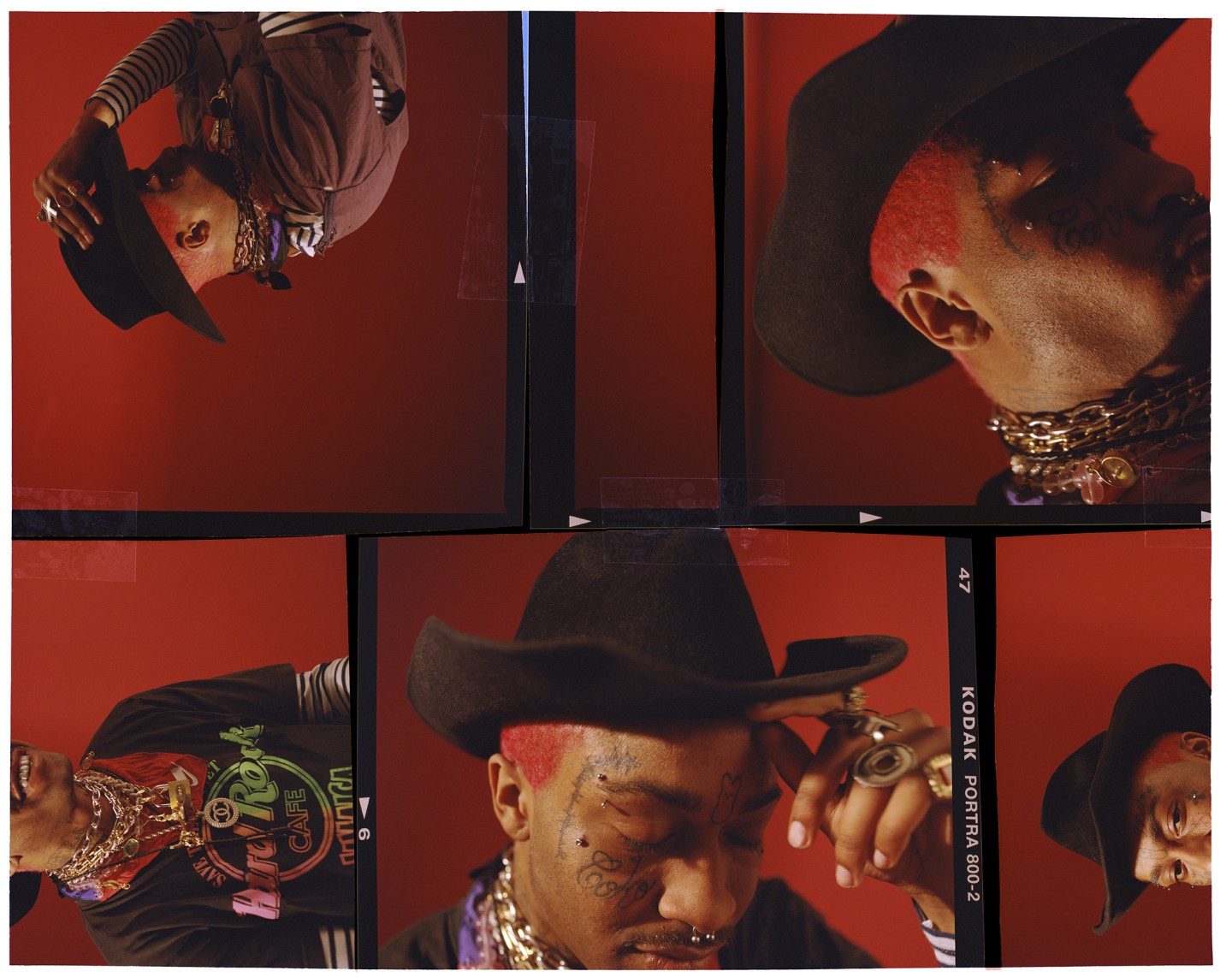

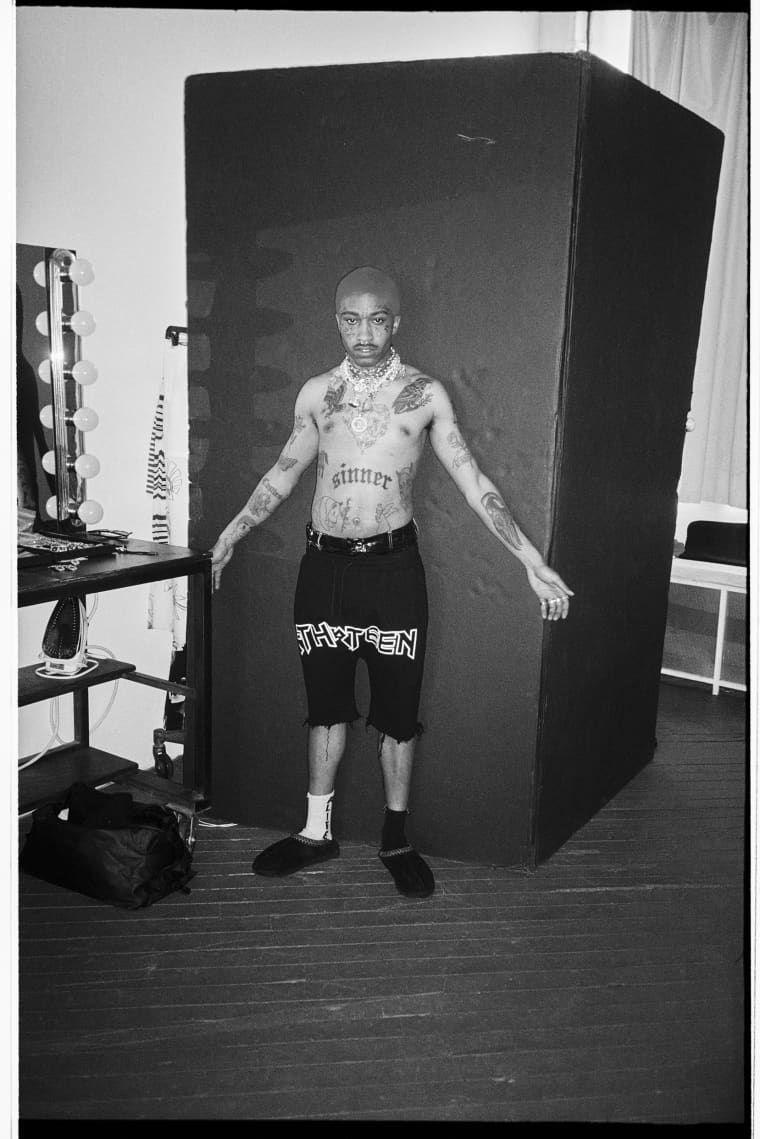

MISBHV shirt, LINDER 'xo' rings, RUSH JEWELRY DESIGN signet ring, TRACY'S OWN dragon ring, JENNIFER FISHER choker, TRACY'S OWN necklaces.

MISBHV shirt, LINDER 'xo' rings, RUSH JEWELRY DESIGN signet ring, TRACY'S OWN dragon ring, JENNIFER FISHER choker, TRACY'S OWN necklaces.

Many others, including Salem, Lil Ugly Mane, Ghostemane, and $UICIDEBOY$, were white. Like Eminem and Insane Clown Posse before them, the latter used gonzo “evil” themes rather than lived experience per se as their entry point to violent imagery. This had a potent appeal to a young, online, and primarily white audience who didn’t necessarily identify with mainstream — i.e. black — rap. Gothboiclique came from this charged environment; Tracy is one of two black members out of ten.

Tracy found himself in a bizarre position: a black rapper viewed with suspicion because of his race. “Even to this day,” he says, “I know for a fact, to some kids, I’m the only black person that they might ever really fuck with music-wise.”

Sometimes fan behavior moved beyond ignorance into straightforward racism. “There was a point where people would mention that I was black everyday,” says Tracy. “There was a trend of everyone commenting on my pictures with the n-word — with the -er. You know how you can go on Instagram and block out certain words? To this day, no one can comment the n-word on my Instagram.”

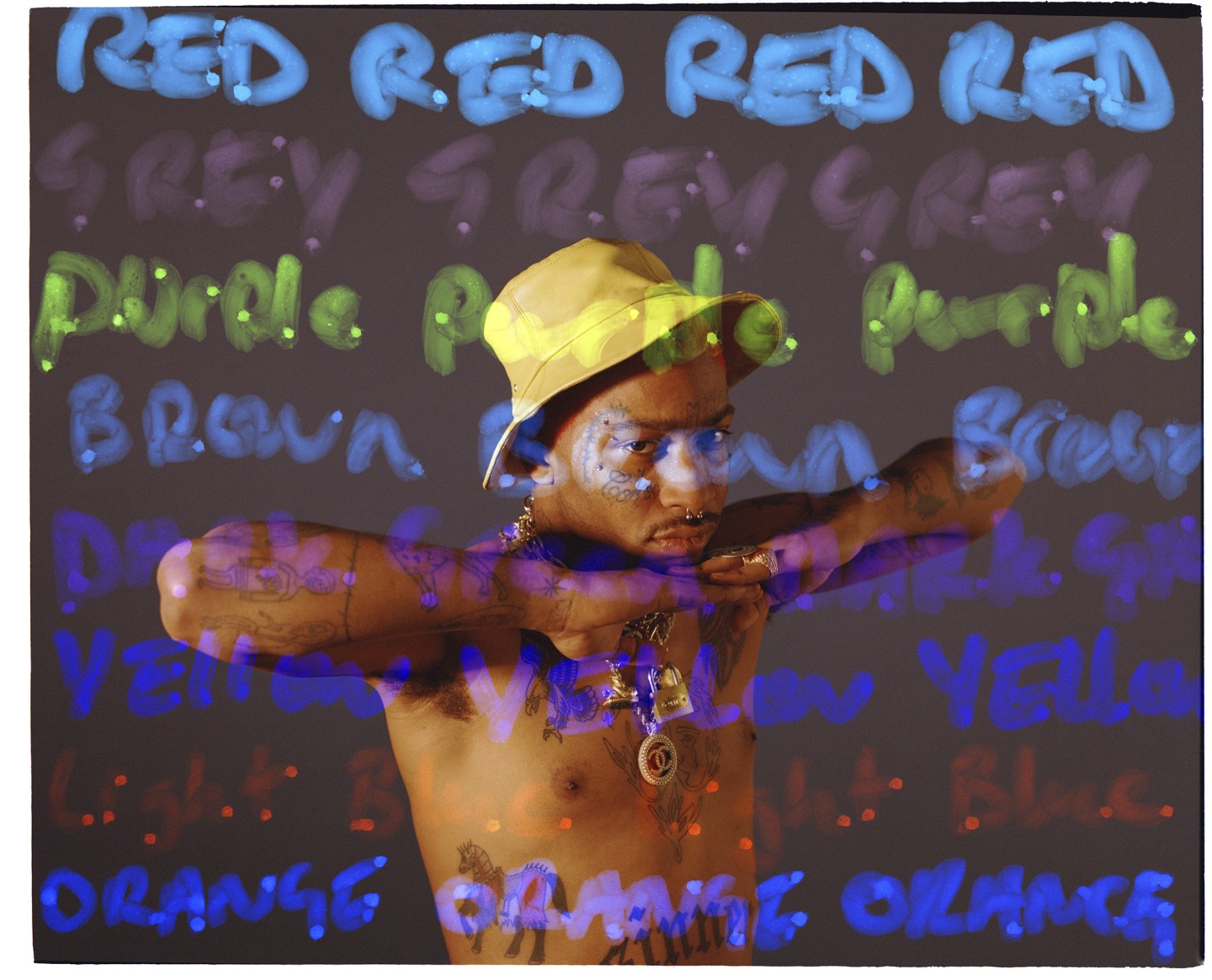

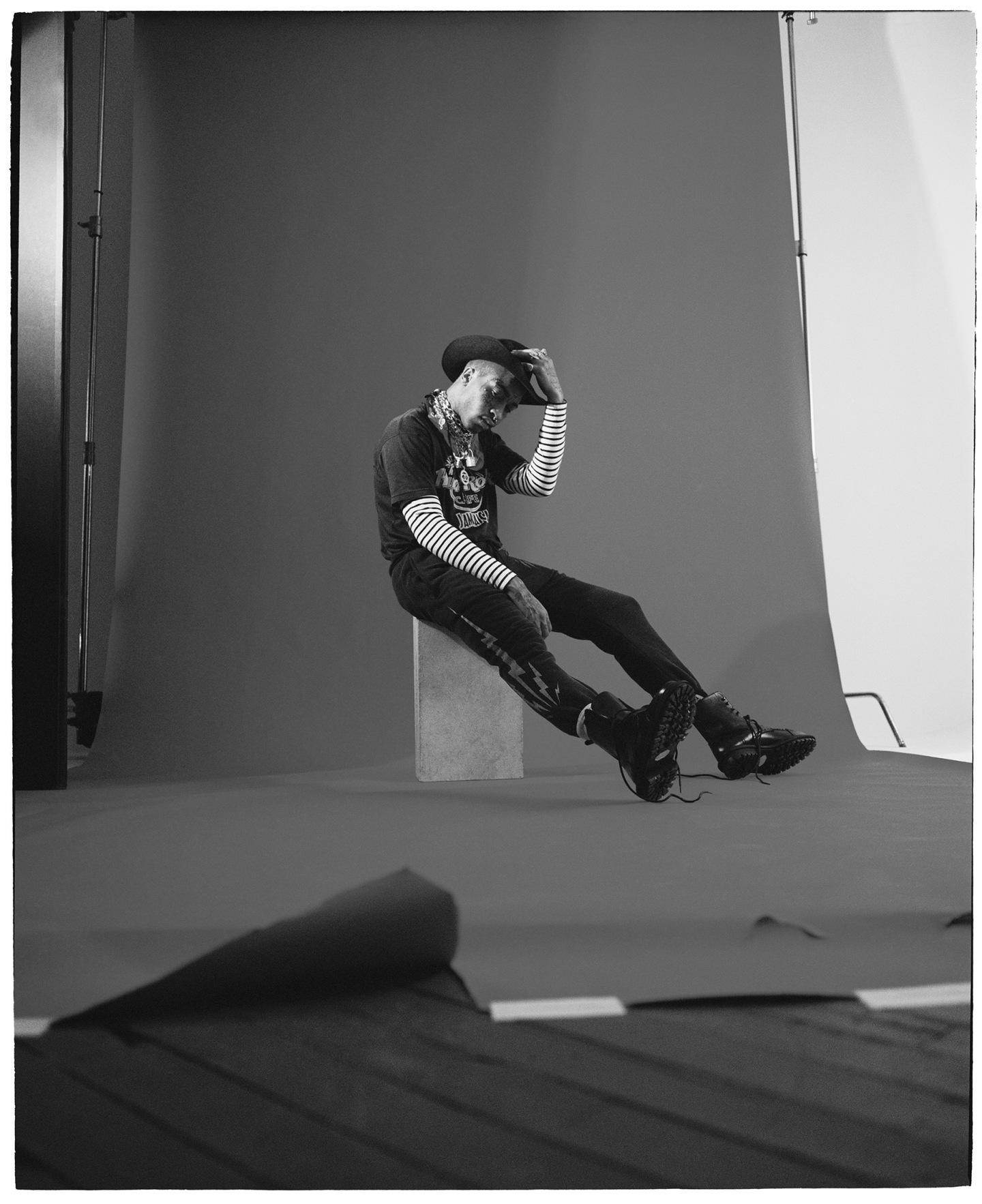

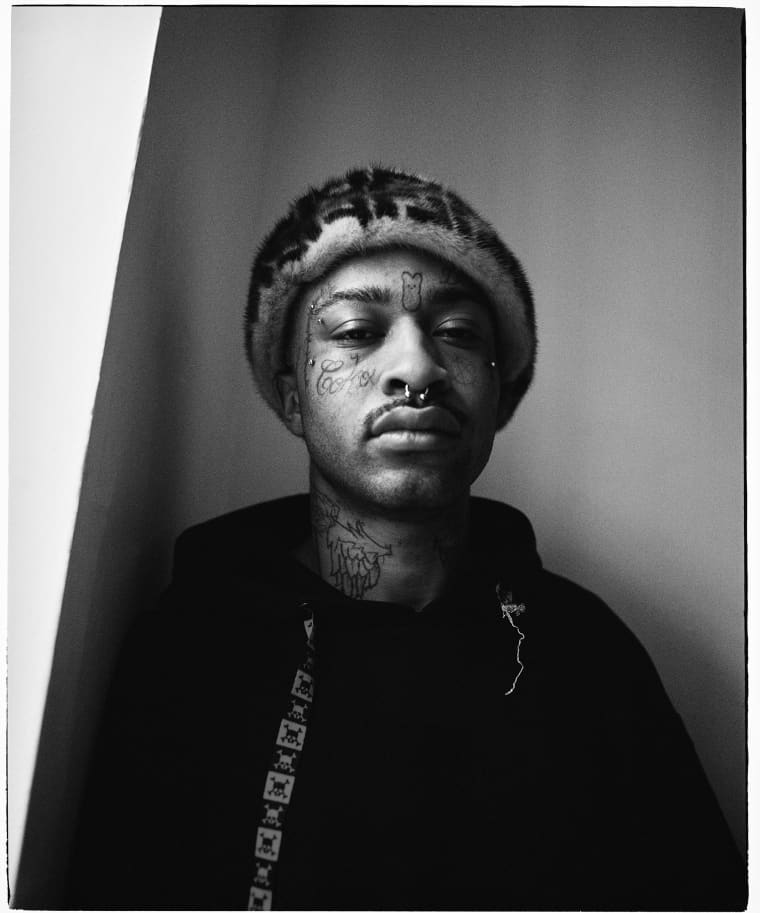

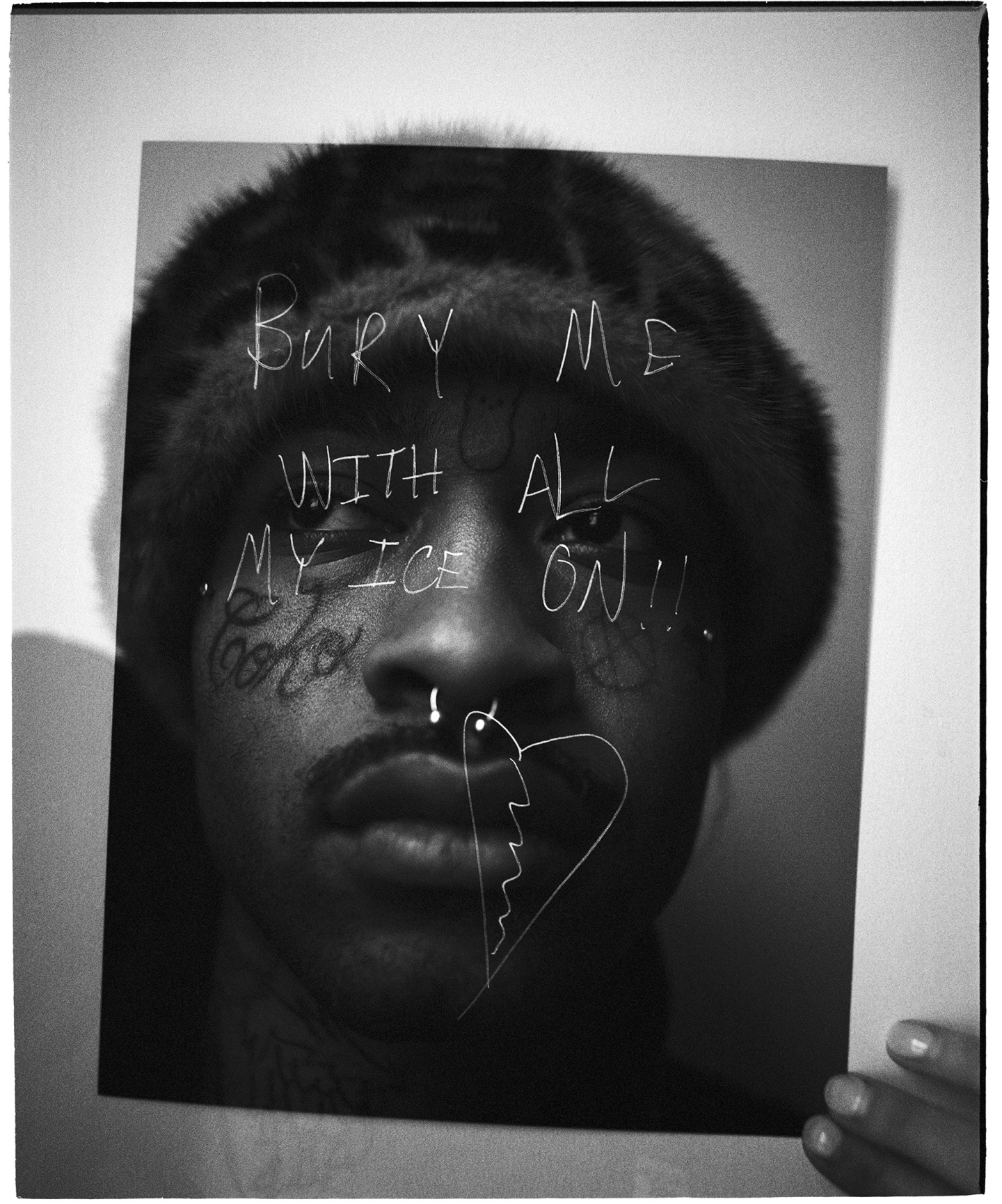

CLYDE hat, OFFICINE GENERALE long sleeve, R13 sweatpants, SACAI shoes, NIKE SPORTSWEAR bandana, STYLIST'S OWN shirt.

CLYDE hat, OFFICINE GENERALE long sleeve, R13 sweatpants, SACAI shoes, NIKE SPORTSWEAR bandana, STYLIST'S OWN shirt.

Then everything changed forever. On November 15, 2017, Lil Peep died of a fentanyl and Xanax overdose on his tour bus. Tracy hadn’t been on good terms with him for a few months, but he’d recently tried to reconnect. He says he was rebuffed by Peep’s management, and “low-key Peep also,” when he asked to come to his Philly tour stop. There’s a video on YouTube of a clearly devastated Tracy performing their collaboration “Witchblades” at a tribute show in Boston a few days later. The raw catharsis on display is palpable. Tracy can’t make it through the first verse, tracing the outline of a heart and covering his tear-slicked face with his hands. The camera is inches away. The crowd roars every word. His tears are a digital monument.

These days, Tracy continues performing his Peep collaborations at shows. At first it felt weird, “because, you know...” he says. “But now I like doing it. It reminds me.”

“[Peep] would do the same,” says Cold Hart. “He would blast our shit if we died. You have to overexpose yourself to it. Otherwise you can never jam out to it.”

The three of us are sitting on the floor of Tracy’s bedroom as we talk about the complicated aftermath of their friend’s death. I ask if things are starting to look up again. “I got AirPods now,” jokes Tracy. “We made it,” adds Cold Hart, brandishing his own pair. “We had to grind for these. Now we can’t hear the bullshit; we just put these on.”

The loss of a friend is a tragedy; the loss of a celebrity friend with an army of obsessive followers desperate for a scapegoat is something else. Tracy moved to New York City in early 2018 as fans blamed Gothboiclique — and, in turn, Tracy — for Peep’s drug use. “They were trying to say that we’re the sole reason he’s dead,” says Cold Hart. “None of our other friends wanted to speak out or help us.”

“When I feel some type of way, I can’t think straight,” Tracy tells me. “I fall asleep thinking about it.” Racked with grief over Peep’s death and fury at the online conspiracies about what exactly happened, he posted “some pretty crazy shit.” In one since-deleted tweet, he wrote,

“Before I kill myself I’m gonna mass shoot kids at shows so be careful coming to my shows.”

Needless to say, that didn’t go over very well. A few days later, Tracy was backstage at the Knitting Factory in Brooklyn with his mom, who’d driven up from Virginia to see him perform. A documentary by Mass Appeal captures what happened next: a contingent of NYPD officers from what Tracy believes to be the department’s notorious “hip-hop squad” swarmed the venue. They informed Tracy that they’d seen his tweet, and he wouldn’t be allowed to perform.

“Then they took me away in an ambulance,” he says. “I felt like the Joker.” I fail to stifle an involuntary laugh and then quickly apologize. “It was funny,” he tells me. “But what wasn’t funny was, I didn’t realize what I was about to be in for.” Tracy was then committed to a psychiatric ward for ten days, a time he remembers as horrible. “I don’t see how that could make anyone feel better. It was really bad.” At one point, Tracy says he tried to leave the institution, but was told if he left, he’d get thrown in jail. “There was one dude, I guess he thought I wasn’t really in there with him,” he remembers. “He would be like, ‘Yo, can you go to the store and get me a soda?’ I’d be like ‘Bro, I can’t leave.’ He’d make me take his money, and say, ‘Get yourself something nice, too.’”

“If your friend died from an octopus attack, would you be sad?” —Lil Tracy

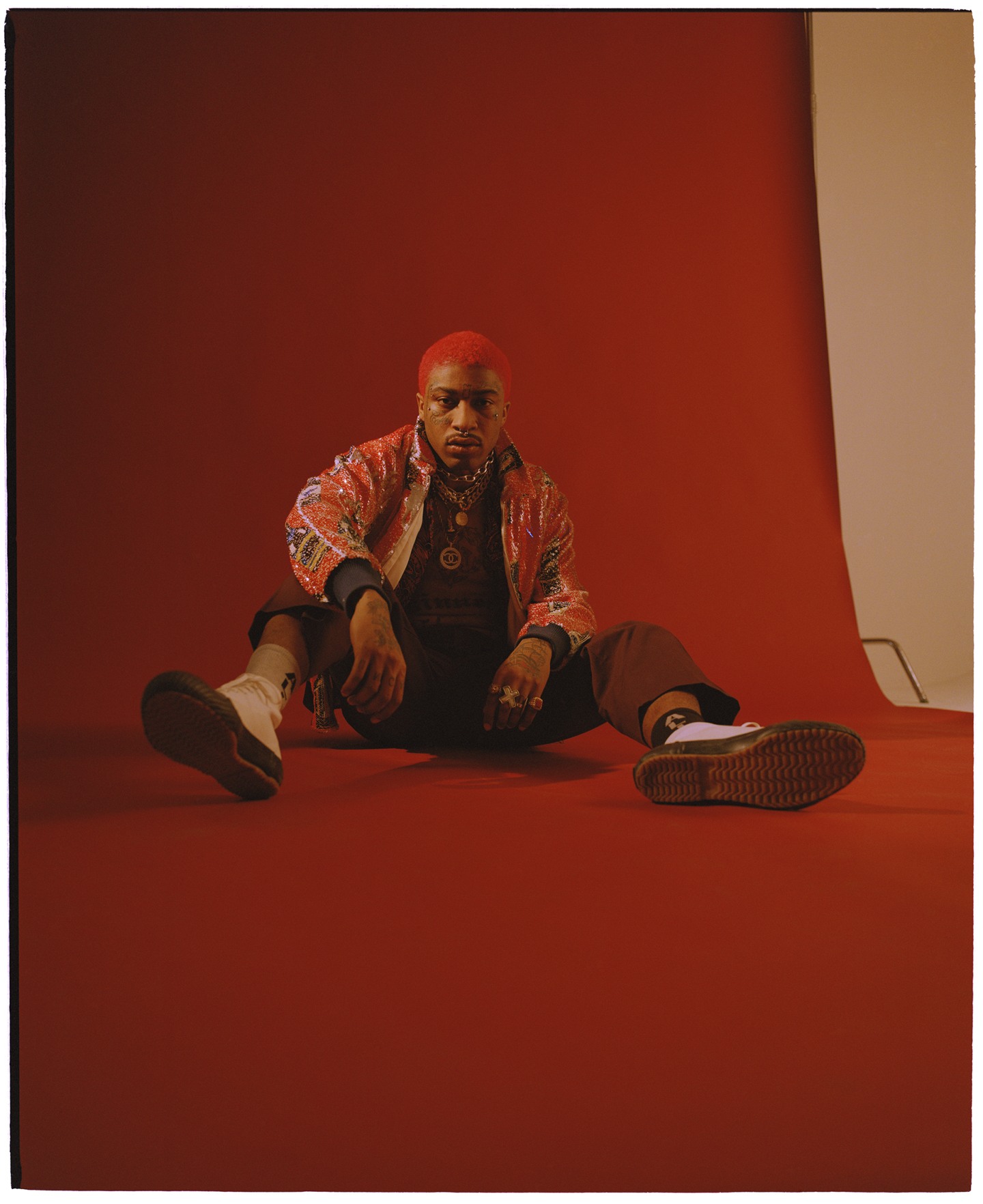

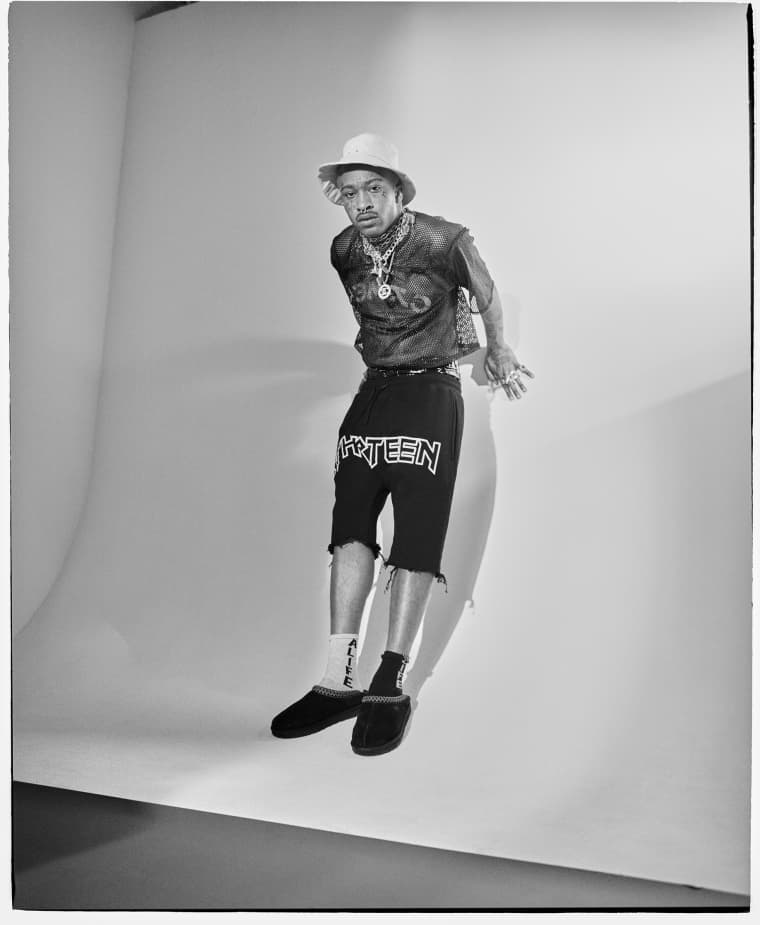

ALIFE jacket, MISBHV shirt, LINDER 'xo' rings, RUSH JEWELRY DESIGN signet rings, TRACY'S OWN dragon ring.

ALIFE jacket, MISBHV shirt, LINDER 'xo' rings, RUSH JEWELRY DESIGN signet rings, TRACY'S OWN dragon ring.

Tracy and I zoom over New York City’s Williamsburg Bridge in the back of his manager’s SUV as he tells me about feeding Percocet to a pornstar’s pet squirrel. In late 2017, Tracy spent a surreal month living in the Miami abode of Bruno Dickemz, a rap-adjacent pornstar known for his “Groupie Lust” video series, in which rappers have sex with pornstars (Tracy filmed a never-released scene). In addition to two pet alligators — which lived in the same guest room Tracy slept in — Dickemz kept a squirrel, which roamed freely around the house.

Once, Tracy and a friend placed a painkiller in front of the little creature. “We didn’t think he’d eat it,” says Tracy, illuminated by the Manhattan skyline. “But he did.” After swallowing the pill, he remembers, the squirrel “just went like this” — he folds his hands into paws and stares glassy-eyed at the ceiling — “and stayed like that for a day. We were freaking out. Then he got up again and started running around!”

Like all Tracy stories, it’s a little twisted and absurd.

Here’s another one. One night in May of 2018, Tracy and some friends got drunk and spent the night “talking like hillbillies.” The accents were based off the “redneck dudes” he knew from rural areas not far from Virginia Beach. Inspired, Tracy searched his email for beats with a country twang, and found an instrumental by Gren8 that fit his purposes. He recorded “Like A Farmer” on the spot.

A tongue-in-cheek ode to Wrangler jeans, Tyson chicken, and Coors Light (with a generous helping of AutoTuned “yeehaws”), the song became a surprise hit online. Soon after it dropped, Tracy received an even more surprising message from Lil Uzi Vert, asking to jump on the remix. The verse he delivered is catchy, detailed, and hilarious. (“You’re cute as a button, but don’t got fake boobs” is a post-rhyme country-trap pickup line for the ages.) Uzi deftly mirrors Tracy’s cadence and lyrical approach. It’s a co-sign not just of Tracy’s latent star power, but of his craft.

“No one would expect that from me,” he says. “People who counted me out — it’s a shot to them. I’m joking around, and I can still go viral. That song helped me mentally. It made me feel like, everything happens, just look at the bright side of shit. Try to laugh.”

In his first few months living in New York, Tracy fell back into heavy drug use after a sober period. “I was dealing with depression, trying to push [Peep’s death] behind me,” he says. As we talk about what happened next, Tracy’s wrapped in a cozy blanket, reclining against the wall next to a pile of stuffed animals — a snake, a sheep, Mickey Mouse, and Winnie the Pooh. His voice never wavers, but occasionally he stares off into the distance.

He explains to me that in July 2018, someone left cocaine in his room. He did a bump. Then he got thirsty and walked into the kitchen, where he found a Sprite on the counter. He chugged it, unaware it was a friend’s THC-infused lean, and went to a bar nearby and drank tequila. His heart started pounding and he went outside for a smoke. Then he sat down on a stoop and felt an “explosion” go off in his body: “I felt like my heart was bleeding.”

Feeling like he was about to die, he tried to run home, hoping someone there could call an ambulance. The next thing he knew, a car pulled up. From inside he heard voices yelling his name. He realized they were fans and ran up to them, clutching his chest. The next day Tracy woke up in a hospital bed. A nurse told him that he’d experienced a heart attack. “My whole left side was numb,” he says. “It brought me to tears when she told me.”

Tracy spent the next month recuperating with his mom in Virginia. “I just let him lay around, and made sure he’s okay and nursed him back to health,” she says. “That’s a very scary situation.” Tracy got sober. “I don’t want to die,” he says, looking right at me. “I’m scared.”

Tracy recently beat Red Dead Redemption 2, and he already misses it. “Watch this,” he says as he stalks an enormous grizzly bear through a shady patch of trees. He peers through a rifle scope, fires, and the bear comes charging at him. It grapples him to the ground and tears at his throat, before his avatar fires a shotgun blast into the bear’s snarling head.

Later that night, Tracy plays me a handful of unreleased songs. Some of them sound similar to his work with Famous Dex and last year’s Designer Talk EP — spacey trap production, clever punchlines, and arrangements that wouldn’t sound out of place on the radio. One song, called “This Is It Chief,” references his health struggles: “I done took a lot of drugs in my days (facts) / I made my doctor’s hair turn fucking gray (my bad).” Tracy marvels at his own line. “Who else would say that?” he asks, shaking his head in disbelief.

He’s also been working on material that’s more in line with his Peep collaborations and the Sinner EP. Think guitar samples, poignant melodies, and lyrics that touch on desire, heartbreak, and death. “For my next project I’m thinking about tapping in with the old shit,” he says. “People wanna hear it, and I think it would be good for my career.”

Tracy’s songs have tens of millions of plays across the internet. He’s headlining a national tour this spring and several dates are already sold out. He’s friendly with A-listers like Juice WRLD and Lil Uzi Vert; if you’re under the age of 25, he’s your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper (even Kevin Durant is a fan). But it’s possible Tracy might have been a bigger star by now if he’d played the game a little different — bit his tongue on social media, pursued a major label deal, waited patiently in line behind Peep, and compromised on some edgy creative choices.

In November 2018, following several months of sobriety, Tracy posted a photo on his Instagram story of three Xanax bars in his hand, captioned, “I’m quitting music, all I feel every day is pain and sadness.” He deleted a bunch of songs off the internet and took the pills, a relapse he now explains was from depression he experienced after reading comments on Reddit.

“What I really want people to know,” says Tracy, with a hint of something deeper than frustration, “[is that] I’m not a crazy drug addict. I’m just a normal, nice dude.” The problem is, since nothing really goes away online, crawling into a new skin is a lot easier than shedding an old one. How is anyone ever supposed to grow up?

One frigid day in January, Tracy, his manager, and I are walking around Manhattan’s Chinatown. Tracy wants barbecued duck. A quick search on Google Maps reveals a place nearby called Funny BBQ 98. Tracy laughs and repeats the name a few times, chewing on the weird phrase. “It better be funny.” The restaurant’s only nod to humor is the tuxedo T-shirts worn by the staff. “I think I could work here,” he says, nodding at our waiter’s shirt. “It’s Lil Tracy, welcome to Funny BBQ. Can I take your order?”

At the buffet, we load up on different meats. Tracy steers clear of the pickled chicken feet — “Bro, are you really about to eat that?” — but he’s all over the seafood skewers. “If your friend died from an octopus attack, would you be sad?” he asks, considering a tentacle. It’s a perfectly cryptic Tracy-ism.

Tracy’s still figuring out what to do with himself since getting sober again. He likes Asian food, shopping for designer clothes, and high-end imported tea. He plays a lot of video games. Sometimes he posts about being lonely on Twitter. After he gets back from his tour, he’s planning on moving back to suburban New Jersey, renting a house, and setting up a real recording studio. He craves space and solitude.

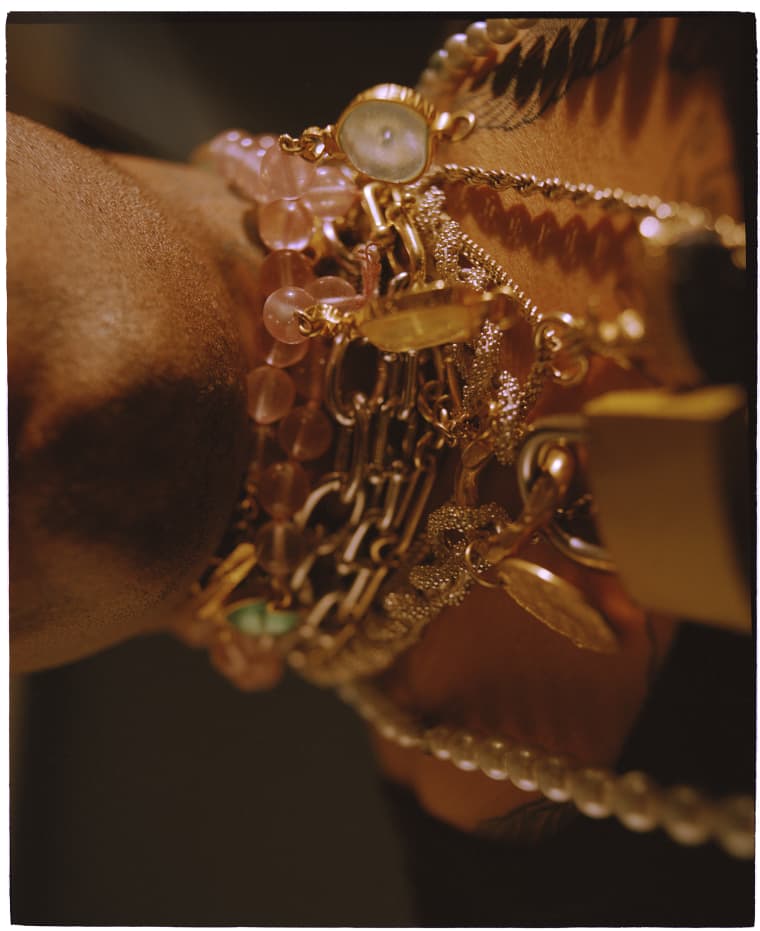

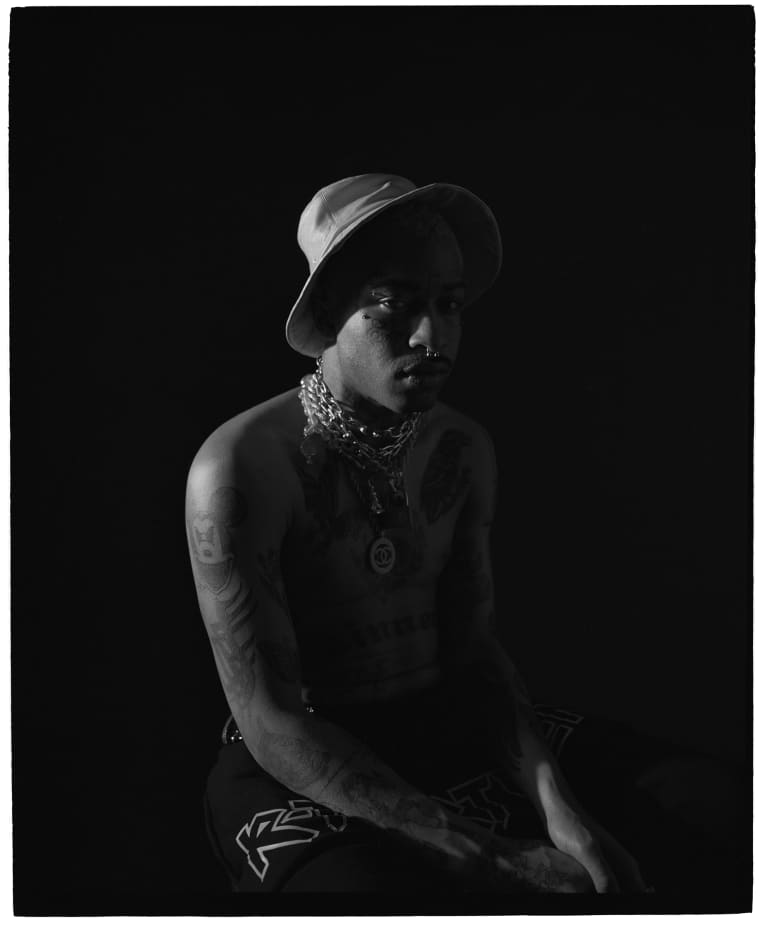

CLYDE hat, R13 sweat shorts, NO.21 shorts (under), TIFFANY & CO bracelets (as necklace), ALIGHIERI coin necklace, DUDLEY VAN DYKE pendant necklace, ALIFE socks, STYLIST'S OWN shirt.

CLYDE hat, R13 sweat shorts, NO.21 shorts (under), TIFFANY & CO bracelets (as necklace), ALIGHIERI coin necklace, DUDLEY VAN DYKE pendant necklace, ALIFE socks, STYLIST'S OWN shirt.

That afternoon we end up at Popular Jewelry, the Canal Street store known for its rap clientele. The walls are plastered with laminated photos of A$AP Rocky, Playboi Carti, and, blessedly, Jude Law, posing with Chiokva “Eva” Sam, the middle-aged Chinese woman who runs the place. She perks up when we walk in.

“Instagram?” she asks, observing Tracy’s colorful hair and face tattoos. He types in his handle. Her eyes narrow as she scans his posts: “Uzi?” She’s spotted a photo of Tracy FaceTiming with the star. “Yeah, we’re friends,” he mutters, smiling a little. “Okay, photo!” she declares, and beckons him behind the counter. An employee snaps a pic and posts it on the store’s Instagram story. Tracy buys a silver lip stud.

As we leave, Eva hands him a red envelope embossed with a golden dragon. “For luck,” she says. He opens it later and finds a fifty-dollar bill.