Photo: Matthu Placek

Photo: Matthu Placek

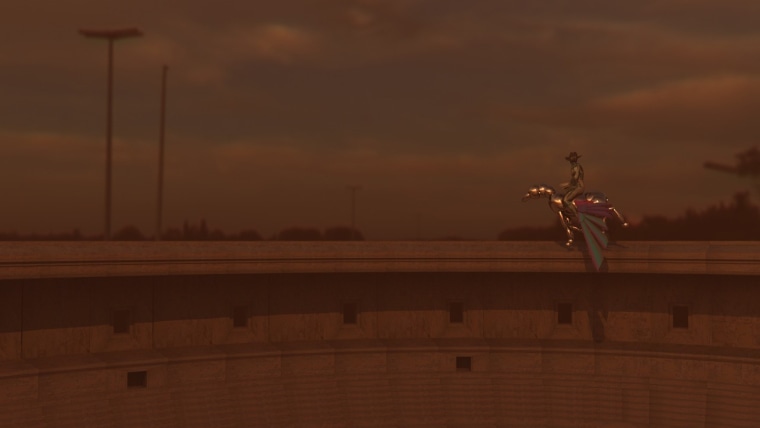

On March 1st, twenty-four hours after she released her fourth studio album, Solange released a film to accompany When I Get Home, with fluid, vaguely melancholic imagery depicting various interpretations of home. One segment towards the end stands out: an animation depicting rows of Black men (and Trina!) dancing as a pegasus floats above, all soundtracked by album cut "Sound of Rain.” The three-minute video is directed, produced, animated, and conceptualized by Jacolby Satterwhite, a multidisciplinary artist currently based in New York City.

Satterwhite works primarily with new media, like film and 3D animation, as well as his own body, often incorporating his image into his work via green screen. He’s showcased his work internationally at galleries and shows including (but not limited to) the Whitney Biennial, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, ASAKUSA, and Whitechapel Gallery, with upcoming shows at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the MoMA.

We spoke with Satterwhite about the process behind visualizing "Sound of Rain".

Still image from Solange's "Sound of Rain" video. Courtesy of Jacolby Satterwhite.

Still image from Solange's "Sound of Rain" video. Courtesy of Jacolby Satterwhite.

How did you and Solange link up?

I've worked with her creative collective Saint Heron for a few years. I did a project with them at the Metropolitan Museum with Adam Bainbridge, aka Kindness, and I’ve done stuff for their online hub, did interviews with them — she’s always been supportive.

I think she first encountered the work at the Studio Museum in Harlem. I'm not sure but we finally just found a way to coincide and work together. She reached out to me for her new album and I was really excited to say yes, of course.

What did she tell you that she want for you to work on?

It was open-ended. I had a creative meeting with her in Los Angeles; it was me and a few producers and directors, and we were sitting around talking, looking at images, looking at storyboards, conversing about where we are in life right now. We talked about family, familial upbringing, the South. I'm from the South, and I know a lot of the directors of the film were from Texas, and I'm from South Carolina, but there's still some congruency with the things that we consumed growing up.

She's very prolific with her inspirations, between architects and movement artists and choreographers. She has a specific palette, and she's obsessed with repetition and geometry and constellations, and so am I. So we mutually agreed about our inspirations and I took all of that, went home, and I began to model architectural sites and figures and scenes and make storyboards and PDF files. She was really trusting and gave me 100% freedom to express myself. It was actually like a dream project in that she trusted my vision, she trusted my trust in her, and so between the fall and the winter I was working on a twenty-one-minute animation that consolidated itself into a three-minute video.

So she chose "Sound of Rain"?

Yeah, I think it was just really organic. And I love that song, I love Pharrell. He's been the most amazing producer ever, since I was a baby [laughs] so it was kind of like serendipity.

What moved you to create this kind of animation?

The song is very liberating and defiant. I like the bravado of the song, the sexuality of the song, and the stamina of it, and I thought that it was a great way for me to do something that was high-camp Afrofuturistic queer. Me being the animator of the project, it was a great way to push the idea of the animated virtual space as a psychological reconcile. I hate using the term "Afrofuturism" just because it becomes a trope, but even before I was younger and in graduate school and undergrad, and making work, I automatically aligned with the principles of Afrofuturism just because I did grow up in South Carolina, in a very weird dysfunctional scenario. And so I feel like my way of being a Black gay man in the world, and reconciling with the regaming of virtual reality, reading science fiction and finding escapism in places that don't look like Earth, and remapping what Earth is in my own way. For me, [since] this project is about her reconciling her past and coming back home and finding peace within, that's how I interpreted it.

Your other work, like Reifying Desire 6, seems to focus a lot more on the human body and psychology, so I was wondering why you extended the metaphor into an Afrofuturistic level when the album is ostensibly about very physical locations and space.

It shows the potentiality for a culture to remain solid, to endure. I used Texas footage in the animation; they're flying over Third Ward, the coliseum is in Third Ward. Me using a futuristic tableau is just a way of saying that this kind of template will endure — it's a more optimistic utopian possibility of stamina. It is a utopic possibility of a future of Third Ward, with like a Roman coliseum and pegasus, black men dancing in crop circles, being free, queer, and genderless. It's an exaggerated camp expression of what all the things in the song were about.

How do you feel like this animation connects with your past work?

Easily, because she gave me 100% freedom! I think that she and I have a lot in common in what we're interested in, so I didn't feel like it was a deviation or compromise. A lot of working with her allowed me to build a broader palette for what I'm working on in my own personal projects. I make albums as well but they're concept albums that show in museums and galleries, and I do performance art festivals with those albums and the visuals and the virtual reality and installations, so when I was working with her, the pressure of collaborating allowed me to find some order to my own things. It allowed me to reconcile with my own upbringing as well; my mother had schizophrenia when I was a child, and she made thousands of drawings. I've architecturally modeled her drawings into these 3D animations, and I've taken the a cappella albums that she recorded on tape and made albums with them. Basically I've dealt with similar reconciling with home — thinking about the South, South Carolina, Jim Crow, the Confederacy, everything that I had to witness as a child is in my work. That's why Afrofuturism is such an important strategy for me because I had to deal with a difficult racist and mental health past that was just pretty much unsurvivable. So I use the spectacle and surrealism as a strategy to decode and deal with those things.

Still image from Solange's "Sound of Rain" video. Courtesy of Jacolby Satterwhite.

Still image from Solange's "Sound of Rain" video. Courtesy of Jacolby Satterwhite.

So this project lent itself to your broader body of work.

Yeah, it definitely does. There are some things that I discovered while animating that I kept for myself and my own work. You'll see it in the summer.

What's the reception been like since When I Get Home dropped?

It's been great! I'm actually so happy about it. The filmmakers and the directors, it's such a crazy network of talent. I couldn't be more grateful to be integrated with this group of people. I have actually always wanted to see something like this happening; I didn't know I was a part of that. I'm pretty much floored.

What can fans of your work look forward to for the rest of the year?

I have a group show at the MoMA next week that's going to be open until June, and I have two solo shows in the fall, at Pioneer Works and the Fabrics Museum.

The overarching theme of the album is the concept of "home," so what does "home" mean for you?

I think that we all grow up and we become distracted by the excess that infiltrates us through social media, through life, through college, through just trying to fit in and assimilate into the public, and sometimes we get lost. It’s just deleting the noise, and paring things down to what is essentially you.