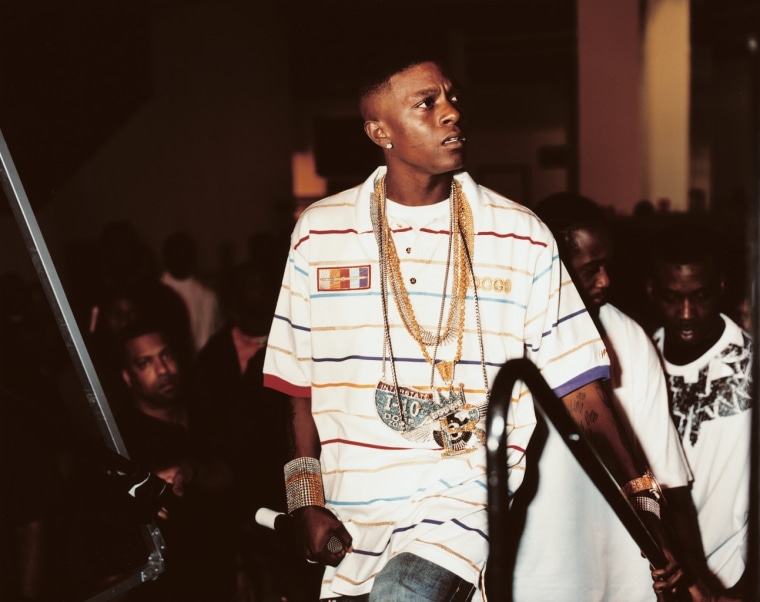

Photo: Jonathan Mannion for FADER 53

Photo: Jonathan Mannion for FADER 53

By trade, Baton Rouge’s Boosie Badazz is a rapper, but for the majority of people who have followed his career and grown with his material for the past two decades, many would argue that the service he provides his listeners is that of a counselor, friend, and shoulder to cry on. Every project within Boosie’s catalogue is a rare — and rewarding — case of music that directly reflects an artist’s life at the time of release. And because of this, the artist born Torrence Hatch has a collection of songs that apply to just about every situation: love, regret, accountability, the desire to ball, America’s prison industrial complex, and more. “Boo was right on time with everything,” Baton Rouge standout Maine Musik described Boosie’s influence in an interview with Say Cheese in 2016. “You got a baby mama, he got a baby mama song. When you goin’ through it with your mama, he got a mama song. When you beefin’ with your homeboy, he got a homeboy song.”

What also links Boosie to so many are the IRL struggles that make it into his music. Since the early stages of his career, he’s been transparent about his battle with diabetes and in the past six years, he’s beat both the death penalty and kidney cancer. Each are markedly American issues that people who don’t even listen to rap can relate to, be it personally or through witnessing loved ones struggle. So while it came as a surprise to many, Boosie’s announcement that he’d be releasing a blues album — arguably the most American genre of music — felt like a natural progression for an artist who’s been bellowing out to the core of what makes the everyday person tick for nearly 20 years. And on Boosie Blues Cafe, an audible space for congregation, the Louisiana native showed that his messages are just as effective when he trades bars for earnest harmonies and 808s for bass guitar

The project’s tone is set early on with the heartwarming “Love Yo Family,” on which Boosie spends the hook singing a rundown of contributions to the family dinner (grandma’s sweet potato pie, moonshine for his uncle, his nephew has the herb). He goes on to — amid warm guitar strums — paint a convincing portrait of relatives playing card games and shooting dice while drinking sugar tea and eating their signature potato salad. But the song’s overarching message is exactly what its title suggests, and not just when things are running smoothly; it means defending people you love and showing up for them in their most dire times of need. In all, “Love Yo Family” feels like Boosie’s attempt at making a timeless hip-hop holiday season record and it has all the ingredients of someday becoming that. But not everything on Boosie Blues Cafe is as joyous and wholesome.

“There are at least 500 shades of the blues,” the late Gil Scott-Heron said in poem “H20gate Blues” from his 1974 album Winter In America with Brian Jackson. “For example, there is the I-ain't-got-me-no-money blues. There is the I-ain't-got-me-no-woman blues. There is the I-ain't-got-me-no-money-and-I-ain't-got-me-no-woman. Which is the double blues.” Boosie shares a variation of each, plus more, while in the Blues Cafe. The I-ain’t-got-me-no-woman blues shows up on “Confused,” a song in which he opens with a monologue about having little-to-no luck settling down, all by his own doing. But instead of brushing his misfortune off with a shoulder-shrug, over some beautiful organ play, Boosie takes accountability and shares conversations he had with a cousin about his love-related strife: “I told him, ‘Cuz, man, I don't wanna be hurt, you know what I'm talkin' about?’ / He said, ‘Boosie, I hear you talkin’’ / ‘But it's crazy 'cause you sayin' you don't wanna be hurt, but you wanna hurt women’ I just stayed quiet on the phone.”

The I-ain’t-got-me-no-money blues appears at different points throughout Blues Cafe when Boosie gets nostalgic — which is often — but it feels especially somber on a couple tracks. “Trouble” is one of the project’s most bare in production, comprised of just minimal bass guitar strums, drums, and tambourine shakes. And on it, Boosie looks back, with some detectable disappointment, analyzing his nearly life-long relationship with being on the wrong side of the law and his last bout almost cost him everything. “I went to prison. I hurt my mama. Hurt my fans. I hurt my children,” then adds “I hurt them babies and that hurts more than anything” for emphasis. “Devil In My Bedroom” is one of the project’s most standout tracks. It features a smoky and spirited hook from Big Pokey Bear as Boosie chronicles the toughest trials of his life which span from witnessing his father fall to addiction to being tried for the death penalty at the top of this decade.

Out of the many approaches taken on Blues Cafe, the most consistent theme throughout is Boosie’s relationship to family and loved ones. This isn’t a new development by any stretch; some of his best work over the past 15 years has centered his gift for translating vulnerability in ways that make listeners feel closer to him than any face-to-face meeting could. 2006’s “I Miss My Nigga” from Bad Azz The Mixtape Vol. 1 saw Boosie go over JAY-Z’s “Song Cry” to eulogize his often-mentioned close friend Ivy; his debut album’s “My Nigga,” encouraged men with hard exteriors to physically embrace their partners (“If you love yo’ nigga, hug yo’ nigga!”); last year’s “Me & Mama” was a beautiful tribute to his mother, Ms. Connie, who he praised for sticking by his side even when he was in the wrong. Boosie Blues Cafe takes moments just like these and places them into one big package — one that suggests a more tender side of a nearly 40-year-old Boosie could be on the horizon.

For a number of reasons, no rapper could seamlessly pull this off better than Bad Azz. In the mid-20th century, Louisiana was one of the country’s epicenters of blues and jazz, with Boosie’s native Baton Rouge particularly being known for its blues culture. It’s also a testament of how the evolution of culture can eventually turn around and inform itself. Rap’s candor and function of giving a voice to those who are regularly silenced is often traced back to blues, which was an evolution of negro spirituals. It’s arguable that no other rapper has carried the spirit of that lineage better than Boosie, who has been one of the foremost Black southern storytellers for some time now. Boosie Blues Cafe checks out because it beautifully illustrates the elasticity of rap in 2018, but also because it perfectly displays the ways in which a maturing rapper can continue to be creative as they age. It’s even better when that creativity can build on a storied legacy and repackage it for contemporary consumption.