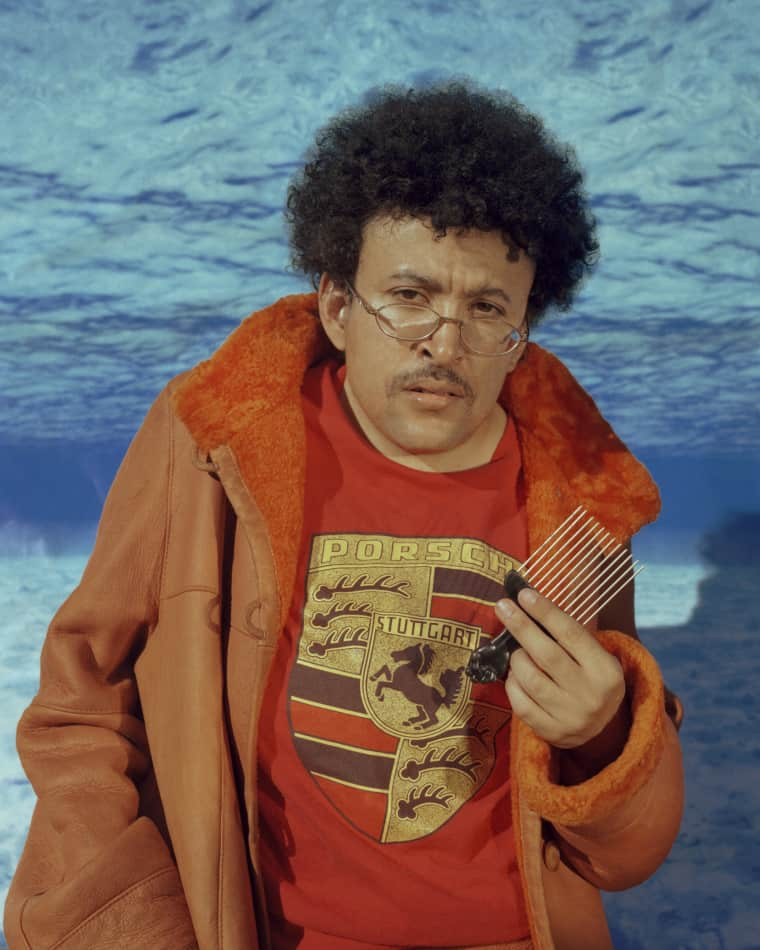

Matthew Urango, a.k.a. Cola Boyy, keeps almost saying “merci” instead of “thank you” to the waitstaff. The 28-year-old musician from Oxnard, California has just returned from a trip to Paris, where he was handling business with Record Makers, the French label partially helmed by electronic space-rock duo Air. Matthew’s pal Luis and his girlfriend Dani, who’ve joined us for lunch at a Mexican grill in Los Angeles’s Eagle Rock neighborhood, chuckle each time he slips up. “They stumbled upon my music on SoundCloud and followed me on Instagram,” he explains detailing the deal he signed with Record Makers in 2017 that led to the September release of his debut EP, Black Boogie Neon, a collection of dreamy, tender disco pop songs.

Paris is a far cry from the “big small town” that is Oxnard as Matthew describes it, and he has no intentions of leaving home despite a burgeoning music career. Though Oxnard is only about an hour’s drive northwest of Los Angeles proper, he says that his hometown, known commercially for its strawberries and culturally for producing talents like Madlib and Anderson Paak, is very different from the sprawling city. “It seems like we’re in a time capsule, like we’re almost a year to two behind things,” he explains. While that may be true on the surface, much of what Matthew says about Oxnard makes it sound like it’s on a timeline of its own.

He came of age in the city’s hardcore skate punk scene, dubbed “nardcore” in the late ’70s when it became a breeding ground for the larger Southern California punk movement, spawning bands such as Ill Repute, Aggression and Stalag 13. For a young Matthew, who struggled with feeling like an outsider because of an inhibiting disability he was born with, nardcore was a refuge. “A lot of us gravitated towards that because it was a place to go and hang out with a bunch of other kids who maybe feel like they [didn’t] belong or fit in in other places,” he says. “The punks that I met when I was in junior high were really nice to me.”

The way Matthew tells it, identifying as a misfit is part of the ethos of Oxnard culture, and almost a source of pride. In a majority Hispanic city with a strong punk history, whose marginalized communities struggle daily in the face of racism, anti-immigration policies, and debilitating gentrification, it doesn’t come as a surprise that Cola Boyy is a local icon. He is a vocal activist and communist revolutionary who works with organizations APOC Oxnard and Todo Poder Al Pueblo. More recently, his talents as a singer-songwriter and producer have flung him onto a more public, international stage — one that he hopes will bolster his political agenda. “It’s my job at this point, and it’s also my hobby. I love to make songs,” he says. “But, at the end of the day my obligation is to the movement, ’til the day I die.”

There’s a rowdy group of Dodgers fans watching the game in the restaurant, but that hardly stops a talkative Matthew from sharing his story. Over a plate of taquitos and a whiskey coke (naturally), Cola Boyy describes growing up in Oxnard, his musical sensibilities, the unique challenges he’s faced as a person living with a disability, and his never-ending commitment to fighting for freedom.

Can you explain the moniker Cola Boyy?

It’s not a very cool story, I just like soda a lot. I made that my Instagram name. I used to spend a lot of time in New York. I’d go visit because I have some good friends there. One of my friends in that crew, his name is Matthew as well. It was annoying because people would be like, “Matt” and we’d both look and it was super confusing. They were just like, “Fuck this. We’re going to just call you Cola Boyy now.” They started introducing me to people as Cola Boyy.

Then I started taking my own music stuff more serious. I wanted to go by my own name, my birth name, but they were like “Nah, fuck that. You have to go by Cola Boyy.” They were like not giving me an option. It was fucking hilarious. Eventually I was like Yeah, fuck it. Once I signed to the label, they were like, “What do you want to go by? Cola Boyy? Your name?” I was like, “I’ll go by Cola Boyy.” It was a good choice because I think people like the name.

What are some distinct memories you have of growing up in Oxnard?

It’s like 85% Latino so pretty much everybody’s Mexican. It was cool growing up with all my friends, skating and scootering and biking around town. Getting into trouble. Nothing crazy, but just breaking things and being kids. I used to do T-ball when I was a little kid. I did some karate. I actually got a junior black belt. My family life was nice. [On] my dad’s side of the family — I spent a lot of time on that side — my grandma pretty much raised us because my parents worked so much.

I have a twin brother, actually. Growing up was cool, but it was also difficult of course getting bullied for being disabled. And like, having a brother who’s not disabled and who looks white. I guess people would argue that we look similar, but he looks like a white guy. That was a factor that was interesting and I didn’t realize so much then, but looking back... yeah.

Most people know Oxnard for the strawberry festival. What’s something different you want people to know about it?

Well, they should know that the strawberry fields come with blood and exploitation. It’s a commonly known thing, but you’d be surprised that a lot of people don’t know this. There’s mad pesticides that they spray over the fields that give people cancer and shit. It’s really fucked up. That’s a fucked up side of Oxnard and there’s a few fucked up sides. I would say the beautiful things about it are the people. The people I grew up with and the people that I surround myself with now are real people who’ve been through a lot. They’re very resilient. There’s so much beautiful things about Oxnard, but at the same time I don’t really want people to move there. It’s already so expensive to live there and the rent is going up and people are getting displaced and it’s fucked up. We don’t need more rich motherfuckers to move in because it’s already hard enough. I would say Oxnard’s dope if you want to come kick it on the weekend and post up with us in like a backyard or alley, or in a park, and drink and hang out. But don’t move here.

Tell me about the scene you grew up in.

It was a hardcore punk scene that was really popular and became really institutional. It’s a big part of Oxnard — a very legendary moment in time that carried on into the ‘90s and 2000s. The punk scene has its strong points and weak times, but when we were in our early teens, it was definitely really popping off. They would have shows at the skate park with, like, a generator. Bands would be playing and people would be drinking, doing drugs, just craziness. When you’re a teenager, it’s pretty formative and pretty cool to become a part of that. Right now it's a little on the quieter side, but there’s some dope shit still going on. It's always going to bounce back.

What is it about ’60s and ’70s music that keeps you so engaged?

As far as the ’60s goes, the early ’60s stuff like girl groups and crooner music is dope. The psychedelic stuff from the ’60s I don’t really care too much for. I love The Beatles of course and the great songwriting from the ’60s, but the ’70s is definitely a lot more influential and inspiring to me, probably because the production in particular is amazing. I learn a lot from it, and the songs are just amazing.

What instruments do you play and when did you start playing?

I’m mediocre at all the instruments I play and I’m decent enough to where I can write songs that I like. I can play guitar, bass, keyboard, and a little bit of drums, harmonica. Of course I sing. All instruments are kind of connected. Once you learn one, you can kind of figure shit out, if you have instruments at your disposal. The first thing I had was a little kid drum set. I was alright. when you’re a kid, you’re either super focused or you’re not. I wasn’t quite ready.

At that point, my grandmother had a piano at her house. It started with me hitting the keys, you know how kids do it? They love hearing the noise and shit. My grandma was like, “If you’re going to play that shit, you’re going to play it right.” I basically taught myself. The first song I taught myself was “Lean On Me.” I was probably like 10 or 11. Then in junior high, I picked up guitar. My other grandma on my mom’s side just had random shit in her closet and she happened to have a little ass acoustic guitar. The other thing she had was a tennis racket from like the 1940s or some shit. She gave me the guitar and she gave my brother Marcus the tennis racket.

I played in punk bands in high school. I did a couple talent shows when I was in elementary school, but like karaoke bullshit. When I was in junior high, there was a talent show and I had tried out. They had these two popular girls who were the ones who got to pick who was in it or not. I don’t know who gave them that fucking power, but whoever did is a piece of shit. Why would you give two popular junior high girls the power to decide who gets to be in it and who doesn’t? I played guitar and they didn’t let me in the shit. No call back. They Simon Cowell’d my ass. It’s OK, though.

As you pursue this career, how is your disability shaping your experience?

I don’t know if it’s shaping the experience, but it’s definitely shaping how I navigate through it, just as similarly as my politics do. It’s changed because it’s the first time in my life that I’m being super open about my disability. Unless you were someone that was really close with me, I never talked about it. It was always very personal and really difficult for me to talk about with people, especially as far as relationships went and being interested in somebody. Having that first conversation was always one of the most frightening things for me. It’s scary. It’s kind of a leap of faith to put it all out there, but it also really feels like a big burden is lifted off of my shoulders. It’s really freeing in a way.

Before you were doing music full-time, did you have other jobs?

When I got out of high school, I tried to find work, but when you’re disabled, nobody wants to hire you because you’re a liability. I applied to all these places, got turned down, got discriminated against. Somebody told me at a self-serve yogurt place, “We don’t think you can keep up.” All you do there is work the register and clean. I wish I would have known now because I would have sued them or some shit. Or threatened to sue them and then they’d give me the job. So, then I applied for disability when I was 18 and got denied. You go to a doctor and the doctor evaluates you, but his job is to try to prove that you don’t need it. His job is not to try to get you disability. He’s on their side. They pick the doctor on purpose.

Then [when] I was probably like 22 or 23 and I got a job at Walmart. They’ll fucking hire anybody there. They had me busting my ass. I did it for like three weeks and then I ended up getting pneumonia and almost died. I had to go to the hospital. I had a tube in my throat for breathing. After that, they were like, “OK, we’ll give you disability now. It took you almost dying.” I’ve been on disability since then. It’s pretty shitty because they put you in this cycle where you can’t really get out of it. They give me $650 a month, but you’re not allowed to save more than $2,000. If you save more than $2,000 you get it taken away.

If you’re on welfare or disability, they don’t want you to enjoy your life in any capacity. You’re not allowed to leave the country for more than 90 days or else you get it taken away. You can’t own any property. If you inherit property, they take away your disability. It’s fucked up. Now that I’m doing my music shit, I’ve started to make a tiny bit of money. Not that much, but next year they’re probably going to take away my disability, which means I won’t have health insurance. But I’m fortunate, I live with my parents at the moment. It’s not fun, it’s not an ideal thing, but that’s still something that makes me privileged. I understand I do have it a lot better than a lot of people. All that time that I wasn't working and was getting disability, I had time to really work on my music, so I’m grateful for that part of it. I got to spend every day writing songs and getting better at it.

I’ve read your thoughts on how you’d like to see more musicians and artists take part actively in the radicalism they preach. I immediately thought of the expression “the personal is political.” Does it resonate for you?

I think this is a true thing, that everything we do is political. Every interaction and everything that we do under capitalism is a reflection of the conditions that exist around us, which are functioning under capitalism, therefore it is a political thing. I do think that this is used as an excuse to not be engaged physically or materially in an organizational sense. Not to say that I’m shaming people who choose not to physically engage, but I would like to see more people do that.

Political understanding is only the first step. The question is what comes after that political analysis and understanding. It should be an action, whether it’s a defensive or an offensive, it should be one or the other, and it should be a step towards some sort of transformation. We can have dialogue and discussion and theory and analysis, and that’s all good, but when are we going to use that to put the fucking fist down and say, “Let’s do this shit, because now we know what’s going to happen”? There’s many reasons why people don’t necessarily engage physically, but they do socially or with words. There’s a lot to lose. It’s a sacrifice to engage physically — for different reasons for different people in different situations. I do understand that.

It kind of reminds me of the sort of thing our parents always tell us: “Well, you know I’m old anyway, it doesn’t matter now. I’m going to die soon. Your generation will fix things. Once we’re all dead, it will get better.” I really find it disturbing because our parents’ parents said the same thing to them and if it keeps happening, we’re going to soon be telling our kids the same exact thing and things are never going to change.

How would you label yourself politically?

I’m a communist, internationalist. I don’t think nations really exist anymore, but I would say I believe in national solidarity and international revolution. I think that we won’t be liberated until the world [is.] Basically, our job is never done. Some people call it permanent revolution.

How do you navigate being a communist and having to survive and operate in a capitalist society? As a musician, you have a record deal with a label, which is a traditional, economic transaction under capitalism.

Firstly I would say, interacting and functioning in a capitalist system doesn’t make me a capitalist. A capitalist is somebody who actually owns the means of production. You know when people say, “You have a phone, how can you be communist?” You know who made this phone? Workers made this phone. The motherfucker who owns Apple? That’s the capitalist. It’s difficult now with the trends of today — the brands and businesses are taking on this vocal thing. It’s fucked up.

At the end of the day, I do have to make a living. I have to survive, but there is a strong line that I don’t cross. Like, brands that are trying to come off as political to sell their gear, that’s whack. I will give an example but I’m not going to say the brand. A brand approached me two weeks ago and they wanted me to go into an internal meeting of theirs and [give] them a five-minute presentation on politics so they can better their branding. They were gonna pay me money to come in and talk to their internal strategy team. So, I told them, “Hell no.” If this brand was like “Hey, play our party,” I would have done that. But, you have this internal motive to try to sell your clothing or your brand by pretending to give a shit about politics or struggling people, when the reality is no, that’s the not the answer. If you want to help the movement, you should give us a shitload of money and don’t ask no questions.

What is your goal as a musician, and where does your urge to create music come from?

I want to be able to live in my own place, have cool instruments to make more music with, buy some cool clothes that I like, and have a moped. I can’t drive but I think I could do a moped. I like meeting people, hanging out, socializing, getting fucked up. Whether they’re somebody from the block or somebody famous, I don’t give a fuck. To me, that’s what this so far has brought me — meeting people, traveling [to] different places, and understanding the world better.

I think as a revolutionary, a big part of it is knowing the world and people who are struggling in similar ways and different ways. [I would like] to have a better platform to talk about the things that I believe in. Those platforms are facilitated by capitalism and corporate as fuck. But I still find an obligation when I’m in those places to talk about the shit I think and believe in. If I make some fucking money, I would like to put it towards some real cool shit. Not some charity that’s run by a billionaire who takes like 80 percent of the profit. The idea is to serve the revolution, serve the people, serve the movement.

What does Black Boogie Neon mean?

You’re the first person in an interview to ask that. Three years ago I wrote a song called “Black Boogie Neon.” It’s about a club where all the rejects and the freaks and weirdos go. It’s a rough-ass demo. At that time, I was still very — I mean, I’m still self conscious as fuck. To this day, I’m still not super confident in myself and my body, but I was in a darker place at that point. One of the lines is like, You’re too fat, you’re too thin, nothing works out in the end. Open the door, let ‘em in. So, that’s where that concept came from. Over the years, I [would] kind of leave little things in songs that mention this club.

Who is “Penny Girl” about? Who are the women in your songs?

“Penny Girl” isn’t really about anybody. It was one of those moments where you take one little, tiny emotional inkling [of] interest in somebody, and you turn it into some crazy story. That one is basically a guy who is in love with girl and he’s so certain that she’s the one. He goes so far, he gets a gun and kills the guy she’s with. He ends up in prison for super long and he doesn’t even remember what she looks like anymore. But he’s so in love with the idea of her. Just illusions of grandeur kinda shit. It’s like hopelessness and wanting to find something in the stars. I was in one of those points in my life where I felt like, “Man, nobody’s gonna love me or care about me.” That coupled with my health getting not so good and feeling like I was gonna die. It just made me have a certain hopelessness and that’s where that song came from.

There’s a sort of little extra song at the end of “Buggy Tip” with piano and strings. That part is about my girlfriend, and me saying even though we are in romance, we must remain dedicated to our organizing. The love we have should extend out and be a part of what fuels us to keep struggling in a revolutionary sense.

Have you always been poetic? Did you keep a journal growing up?

Maybe I wanted to be deep. I don’t know if I wanted to be poetic, [but] I wanted to be a rapper and a singer. I always wrote little stories. It was always really bad. Even a few years back, it was pretty bad. There are some people I think are born with something very special, very intuitive. But I think anybody, with dedication, practice, focus and understanding, can write something nice or make some nice music. I used to think it was magic to make music and write a song. But it’s not. It just takes letting go, focusing, practicing, trial and error and not giving a fuck — just being true.