Another Country is The FADER's newly revived monthly country music column.

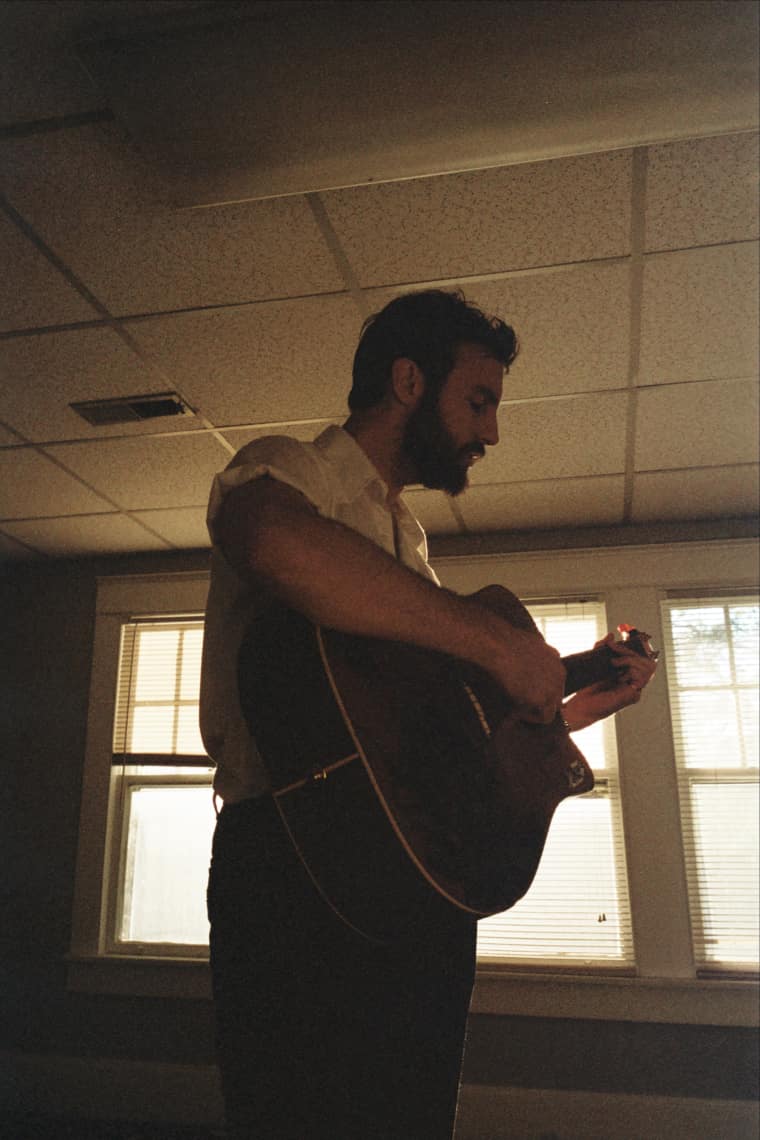

Ruston Kelly is sitting in the corner of an East Nashville bar talking about exploding stars and the speed of light when he suddenly calls out to a man walking past our table from the bathroom.

"Sweet shirt, dude!" Kelly says, putting down his iced coffee. The tee that has caught the singer's attention is for Behemoth, a Polish death metal band known for songs like "Wolves ov Siberia" and "The Satanist." "God, I love them,” he adds. “I love black metal." On most days, today included, Kelly can be found wearing a shirt from either Slayer or Metallica — when he's not in a tailored stage suit or khaki-colored coveralls to paint in.

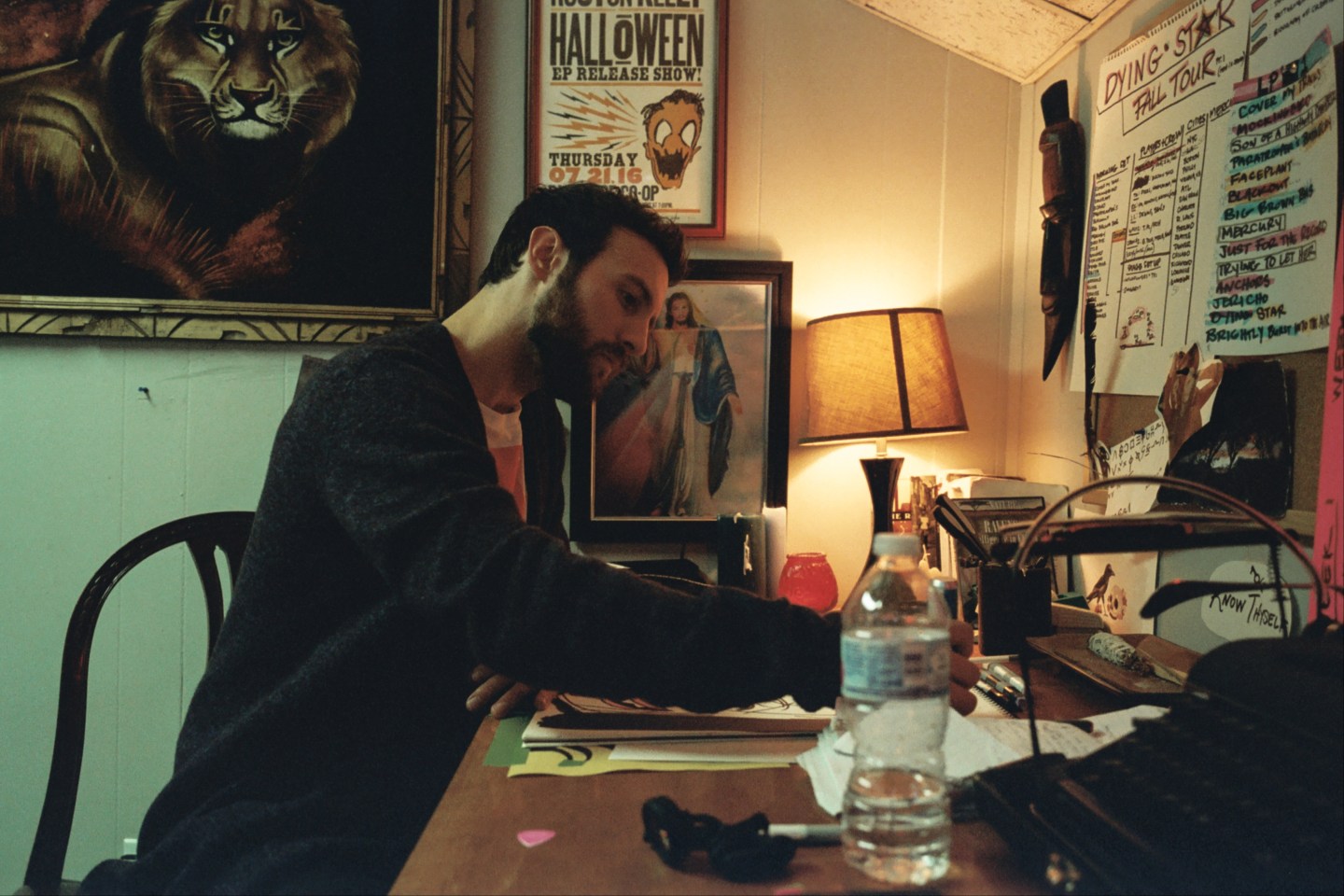

Kelly moved to Nashville at seventeen after a childhood living everywhere from Belgium to his home state of South Carolina, spending time in a jam band, devouring Johnny Cash and scoring songwriter cuts for the likes of Tim McGraw. His first EP, Halloween, was produced by Bright Eyes’ Mike Mogis, but it’s on his debut LP, Dying Star, where he truly settles into his voice. Written in the wake of an overdose and telling a narrative story from deep, dangerous lows ("Faceplant," a chronicle of bad choices on repeat) to his own breed of imperfect rebirth (the album's closer "Brightly Burst Into The Air"), it's a uniquely emotional and raw collection about our ability to build a new life from the ashes.

“All I want to do is sell tickets and make a couple babies with my wife.”

He says he found inspiration in the idea of destruction — in how a star, when it's taking its final gasps of life up in that giant sky, explodes into a glorious intergalactic fireworks, sending its energy out into the universe as it breaks apart. "Deconstruction can be a constructive thing, if you allow it to be the right kind of deconstruction," he says.

And these days, Kelly is focused on rebuilding. He quit hard drugs and smoking, and he's started running, too. Sometimes he'll jog by the elementary school near the home he shares with his wife Kacey Musgraves and think about what it might be like to have kids one day. Good, healthy things. At 30, he is finally in a place where he's both looking to the future while accounting for the past.

"I can write about pain without experiencing pain, which I am thankful for," Kelly says. "But I lived this record. My life's mission is to just tell what my experience is. Because I really did make it out of the woods. Some people don't."

You sing pretty honestly on Dying Star about the state of mind you were in before this album was made: blacking out, overdosing, not being able to make a relationship work. But you actually recorded it after getting clean — the opposite of the narrative we're often fed that artists need to be intoxicated and miserable to make good art.

I used to feel that if I wasn't living out my songs, I wasn't doing myself or my craft justice, and that's a dangerous way to live because then you become what you make. I think it's bullshit when someone thinks you have to be fucked up on drugs to make accurate or moving or even melancholic observations of what you see in the world. In fact, I believe that I can experience my craft even better with a clear head. You can be whoever you want to be when you are writing songs.

And it seems like your creative epiphany really came along with that clarity.

Yup. The day after I overdosed I was just standing on my porch, thinking, "I don't even know where to begin." It was at a point where I had already been to rehab, and that didn't work out, and I thought that if I couldn't figure out how to change this myself nothing could. Suddenly the words "Dying Star" popped into my head, and then "brightly burst into the air." Immediately I knew it was an album title, and the last track. So I called [producer] Jarrad K and told him and he said, "Wait a minute, aren’t you in the hospital right now?"

That's a reasonable reaction. But it makes sense that you had rebirth on your mind — rebirth after destruction.

As a star is dying, it's the most beautiful explosion, but it also repopulates the universe with new stars. I applied that metaphor to my life and used it for my benefit. That's what "Brightly Burst Into The Air" is. Reimagining yourself. You gotta let something pass.

Was it cathartic, making this record?

It was 100% cathartic but it was also fucking terrifying. I was dead sober — well, we ate mushrooms, but I don't count psychedelics. That was really the only vice, and for just one day. We tracked a few of the song's first takes while we were tripping with my dad [steel guitar player Tim "TK" Kelly] at the Sonic Ranch [studio]. He's never eaten mushrooms. I told him before we left, "Dad, you know I don't fuck with any of that other shit. But I'm going to eat mushrooms out here, since we're in El Paso in the desert, and we owe it to the atmosphere." And he was like, "Well, as long as you give me some."

“Calm the fuck down, we are not going to write about a fucking Dixie Cup in a truck.”

Have you had a chance to speak with other artists about the struggles of sobriety?

I texted [Jason Isbell] the other day, which is weird to say, as I've been lucky to pick his brain about what it means to be a sober artist. And he gave me some really good advice and said, 'you're on the right track, so stay on the right track and it's so much more rewarding.' Hearing someone I respect so much say that meant a lot.

And you recruited some other artists you respect — Joy Williams, Natalie Hemby, and your wife — for this album, who happen to all be women. Was that an intentional choice? You don't seem at all afraid to express your feminine side.

I've always felt connected to femininity. I purposely asked predominantly women to sing on this record and be a part of it creatively. We are all dually feminine and masculine. To give in to both of those things would strengthen us as human beings and there is such a drastic difference between men, and men who are terrified of their own femininity.

Most men on country radio these days seem pretty terrified of appearing at all feminine, or expressing "feminine" emotions, though.

If they knew what they were doing, they would embrace it. Plus, I've always felt like women should rule the world. At one point I told my publisher, I only want to write with women from here on out. Because every time I got into the room with a guy he wanted to flex as hard as he could. I was like, "Calm the fuck down, we are not going to write about a fucking Dixie Cup in a truck."

“There is so much good quality music and talented people male and female, even more so female, that should be stars of country radio but they would rather play fucking Cole Swindell.”

And yet that's exactly what gets played on country radio – instead of women. You haven't been afraid to point that out.

Balding white men ready to grab the ass cheek of the next "hot starlet" who walks through their office, I have literally seen that. It's disgusting. Turn on country radio and it will make you sick. We get it; you love to go out on Friday night! There is so much good quality music and talented people male and female, even more so female, that should be stars of country radio but they would rather play fucking Cole Swindell. And some of those guys are my friends and I'd fucking say it to their face, because they know it.

And this is a critique coming from inside the business — you've had cuts, too. The exquisite "Trying to Let Her" was supposed to be recorded by Kenny Chesney.

Chesney cut that song three times. The first time he cut it, [producer] Buddy Cannon called and said, "We've gone through one hundred songs and this is our favorite, we're thinking first single." And he took it off his record. And then he did it again. His reasoning was it was too left of center. It's not chilling on a beach or trying to chase some girls. It would be nice to have some money in the bank — shit, he can still cut it.

I hope he hears it.

I'll make sure he hears it. I'll drive to his fucking house.

Report back — I have always pictured Chesney's house to be in the middle of a magical ocean, surrounded by a moat of summery beer.

Oh, for sure. You pull up and there's like, an ocean there and his own Corona brewery. Anyway, I am not too concerned about massive success. All I want to do is sell tickets and make a couple babies with my wife. Popping out of the bus and coming home to my wife and kids. Now that's what sounds like a dream.