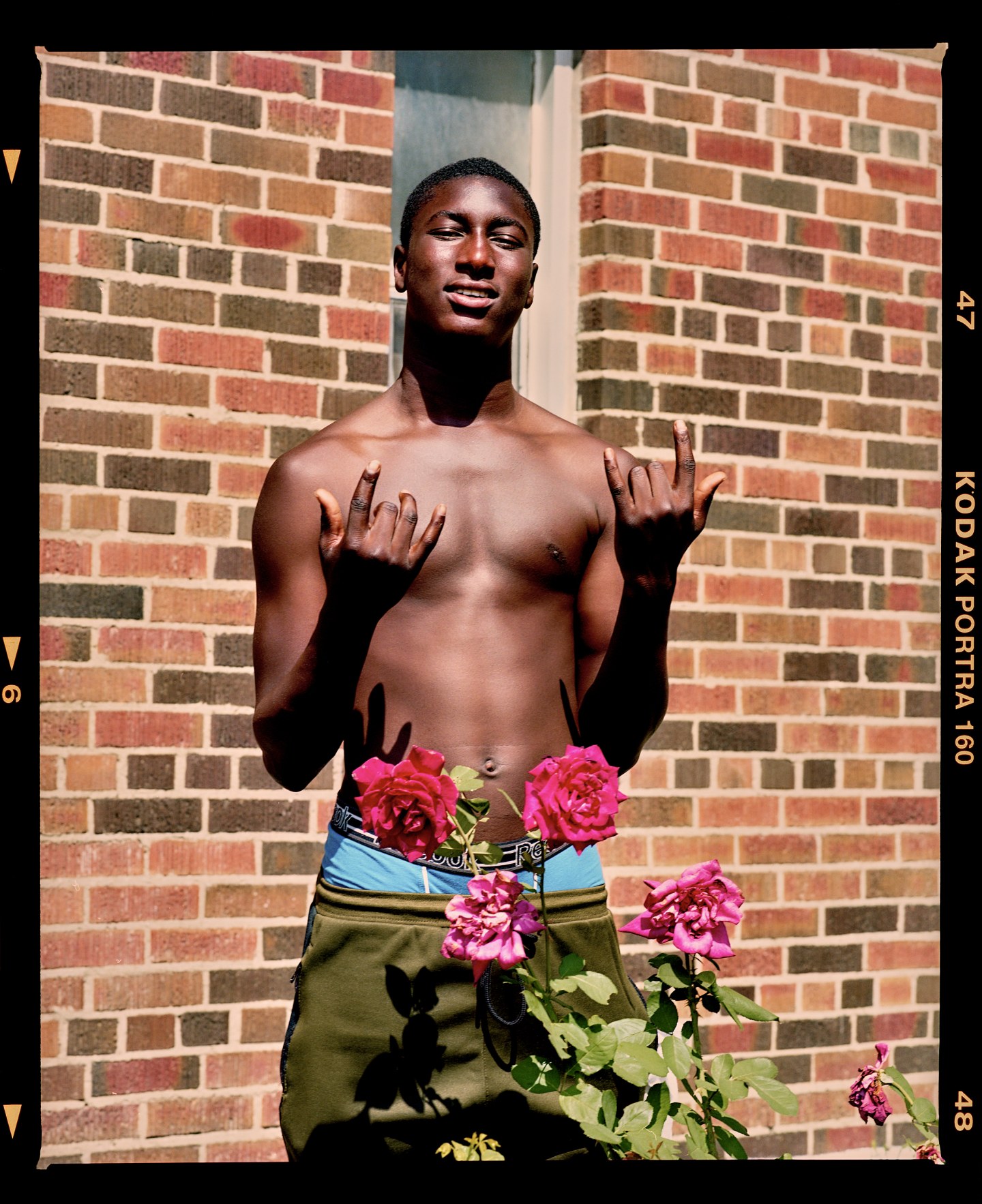

There’s no mistaking that the ice cream truck belongs to Lil Berete — today, anyway. The 17-year-old rapper’s face is wrapped around the stubby vehicle in the jet-black cover art for Icebreaker, his debut mixtape. The truck is at the last stop of a release-day promo event, parked outside of the Kiwanis Boys & Girls Club in Regent Park, a downtown Toronto neighborhood that sprouted up from a housing project in the ‘40s. Yaya Berete climbs on top of the truck. Assembled below are dozens of smiling children and supporters wearing T-shirts bearing the name of his music collective, Southside to Northside. Frozen treats in one hand and phones in the other, they capture his triumphant poses.

Once everyone has a photo or video for Instagram, Berete adjusts his white tank top and black track pants, hops off the roof, and melts into a sea of the Regent Park community he was born into. Later, he describes the feeling of catching his neighborhood off-guard with the quality of his music. “Them people, they knew who I was, but I know they definitely didn't know I was coming like that,” he tells me later, his voice made richer with self-satisfaction.

Press play on a Lil Berete song and you’ll hear the staples of street-rap in his lyrics: he raps with a death grip on life’s decadent things with the pain and promise of betrayal never far off. Where Berete excels is in his ability to use cadence, flow, and his own range to keep the songs swimming in your head as long as most chart-toppers would, with syllables flipped and stretched. His talent is intuitive and precocious, for someone too young to drive the black Nissan we’re riding in after the ice cream truck event has ended. His friend, 19-year-old DK, drives us to a convenience store for a Backwood. “I like songs that put you in a different mood when you listen to it,” he says, smiling, then explains why he’s picky with beats. “I don't rap trap. I have melodies, but I need the right beat. I need that Chris Brown, DJ Mustard type of shit. Slap on some AutoTuning, and I'm good,” he says, and starts rubbing his hands like a meal’s been placed in front of him.

Berete’s been paying attention to melodies all his young life. He cites Young Thug, Akon, and T-Pain as influences, but everything started with his mother, a Guinean artist named Cheka Katenen Dioubate who performs jeli, a West African praise music. Despite his affection for music, he says his formal arts education was limited. As a child, his behavior was too much for his single mother (he is the middle child, between two sisters). “I was too young to understand how life was,” he says after I ask why, at age eight, he was sent to Guinea to live with his aunt. Berete’s easy smile and sleepy eyelids lose their lustre when he talks about the past: he says he lived “the real slums” of Conakry, Guinea’s capital, for four years, and missed Regent Park so much he would dream he had returned. But he credits the experience with teaching him patience. “Everything you do or make [in Guinea] has to be organically, off just your hands. You see how here if you want bread you can just go the store? [Over there] you had to make your own.”

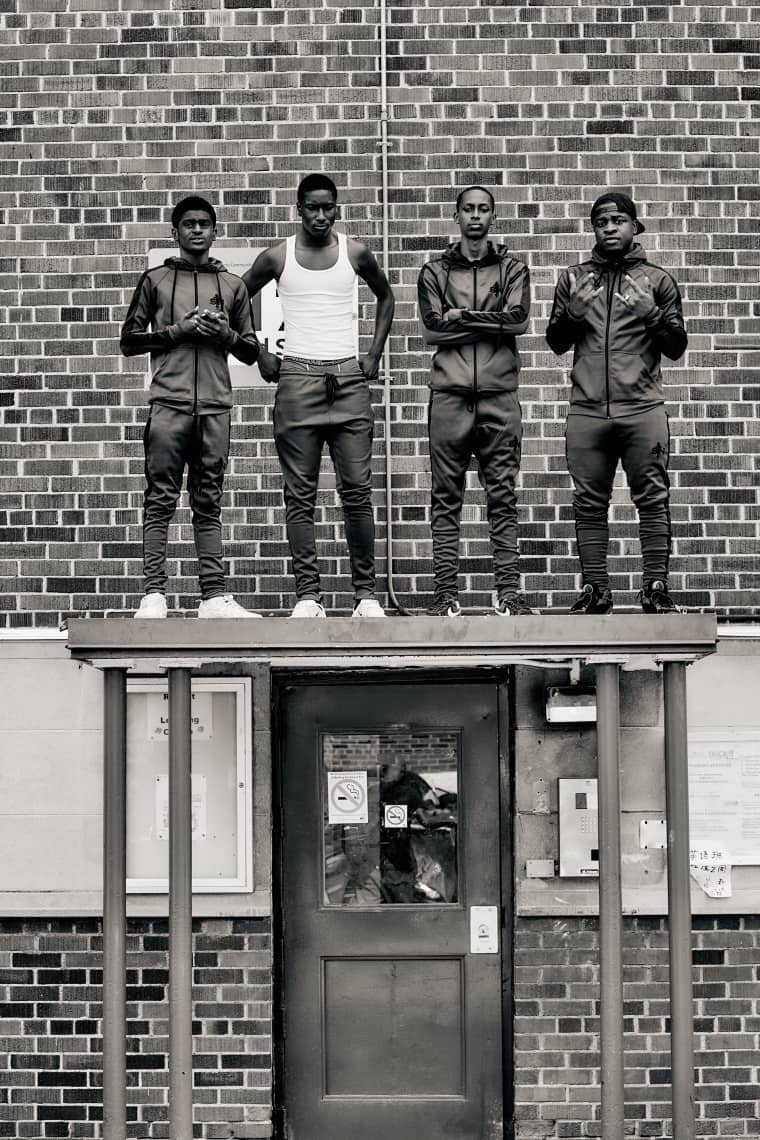

When he returned at age 12, Regent Park still toed the imaginary border of “northside” and “southside” neighborhoods. “The northside would never came deep to southside, like ‘Oh we're coming just to chill here,’" Berete, who lives on the southside, says. “[With] Southside To Northside, I made both sides realize we're one.” Berete’s interest in rap was nurtured by his friend from the northside, Acerrr. “[He] used to show me bare freestyles,” Berete recalls, “and I'm like, ‘I gotta start this shit.’” A year after Berete first heard the beat, he dropped “Turn Up” in September 2017, a song he says got him respect from the northside. But it was “Real,” the Acerrr-featuring banger released two months later, that put Berete on the radar of at least four major record labels (he’s currently signed to New Gen, a subdivision of XL Recordings).

These days, Berete, who confesses he didn’t used to take rapping seriously, is in the studio at least four times a week, creating whole songs off the top of his head. Icebreaker was recorded in London, L.A., and Toronto with producers like Kenny Beats. Each of the eight tracks hones the unique songcraft Berete displayed on one-off singles like “Northside” and “Southside,” while flirting with top 40 radio as on the dancehall/EDM inflected “Time Flies” There are moments where Berete uses it to get personal and it can be overwhelming: his cadance gets tender on “Migraines,” a shift that become tragic when the hook reveals his mind’s lingering paranoia. "I have to live life before I go in there," he says of the studio and his creative process, "'cause sometimes when I go in there and there's nothing in my brain, I just start saying stupid shit, and I get cheesed out. You have to go in there knowing what you're gonna talk about."

Regent Park, Berete explains, was the first public housing project built in Canada. For years, it has been riven by gang-related gun violence, a manifestation of issues cited in a 2008 province-wide report. The fuel comes in many different forms: poverty, dire economic prospects, and generational neighborhood rivalries. “You know in Africa they just sacrifice the chickens?” Berete asks with a grim, distant expression. “Niggas be doing that here. Killing each other. Cutting each other's necks off.” He hopes Southside to Northside will help ease the city’s violent year, which this year claimed the life of his friend Smoke Dawg, a 21-year-old Regent Park rapper who toured with Drake. “We used to go in laundromats, getting high and freestyling, like two-and-a-half years ago,” he says, and fidgets with the embroidered StN logo on his pants. “It was just running in and out of buildings with security chasing us.” Berete is understandably reluctant to get into specifics on how he’s run afoul of the law, but says his lyrics aren’t based on speculation. “A guy can't just go talkin' how we talk in our songs,” he insists. “They didn't really live it. You can't make this shit up, and if you do make it up, niggas will know.” So it’s about authenticity, I say. “Yeah,” Berete says, then looks out the car window for a moment.

Berete knows he doesn’t have to be in Regent Park to be loyal to it. He hopes his career will allow him to one day move to Amsterdam, where his stepfather’s family lives. Now, though, he’s simply too hot: in his rap career, to attend school, and for the police. One evening this summer, Berete and a group of friends were stopped by police officers and issued tickets for jaywalking. Both the young men and the civil rights attorney who shared the incident on YouTube claimed the boys had been victims of racial profiling. Near the video’s beginning, the attorney hands his phone to Berete, who introduces himself to the camera, cheeky and defiant. Even in such tense situations, his charisma is apparent. On record, it blooms. He tells me he uses his last name as his rapping alias in tribute to his father, who died in a car accident when Berete was a boy. It’s why he’s prepared, for anything. “I keep telling myself, his last name told me to be ready. Be ready, Berete.” Suddenly, he gets bashful. “Does that make sense?”