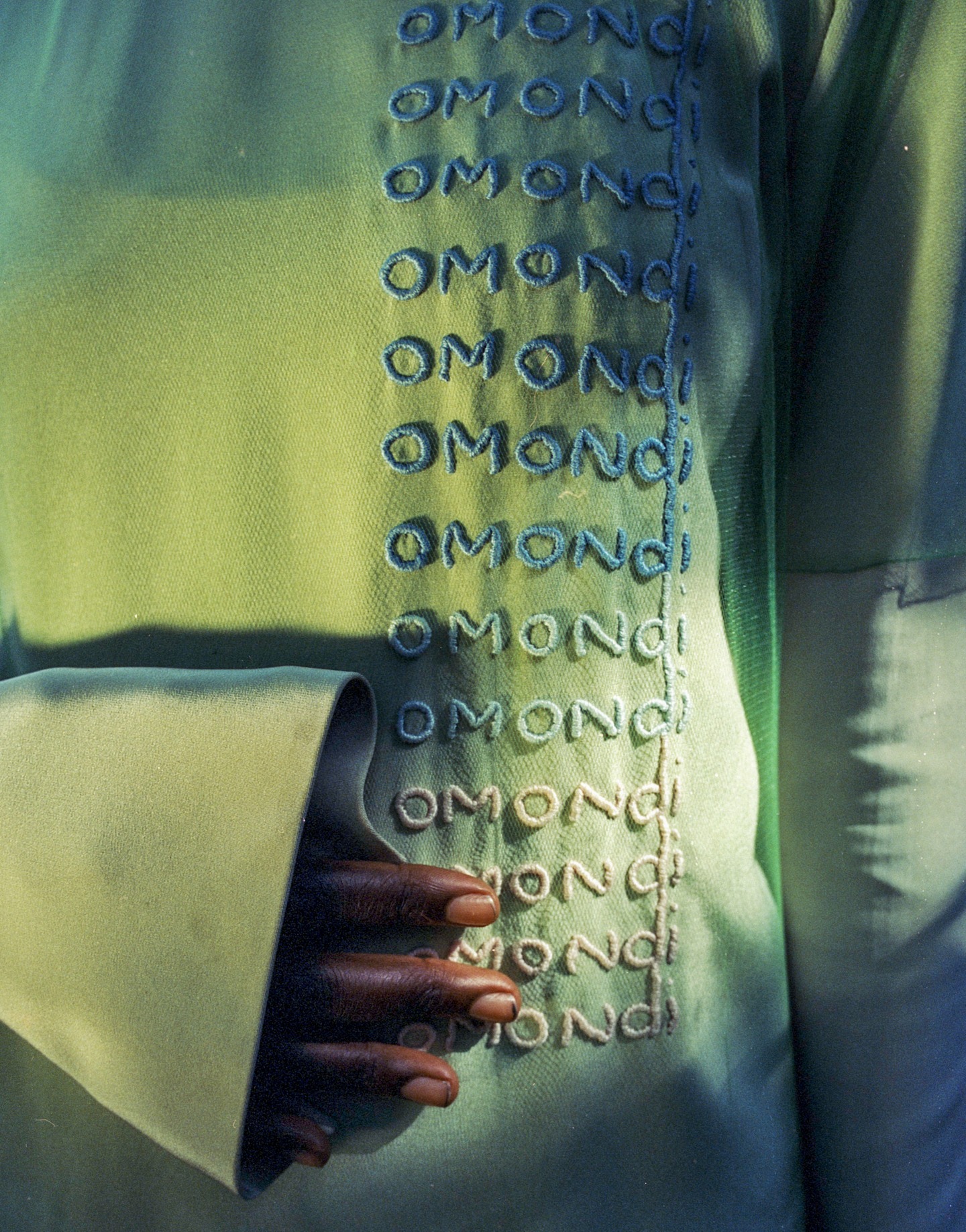

Recho Omondi in OMONDI Vizcaya dress.

Recho Omondi in OMONDI Vizcaya dress.

On an unseasonably cool July afternoon, the fashion designer Recho Omondi sits in her backyard garden, smoking a cigarette. Her outfit — a gray sweater worn over a strapless jumpsuit she created for her eponymous label, OMONDI, and an ever-present Yankees baseball cap — perfectly matches the day’s weather. Over the last year, Recho, 31, has emerged as a voice in New York’s independent fashion scene. She stands out in part because she isn’t afraid to criticize designers by name or frown upon fashion’s old-guard traditions. “People love a pauper-and-the-prince story in fashion,” she says, in between drags of her cigarette. “Even if you got $150,000 from your grandparents, people want [to say], ‘Oh, I just started making clothing in my bedroom.’ You don’t start with nothing, even me!”

Unlike most brands, OMONDI releases just one sensuous collection a year. “It makes no sense designing six collections a year,” Recho explains. “Designers should be able to sit at the sewing machine and make the work!” Since 2010, she has done just that, making clothes that are purist, romantic, and saturated in color. The brand has produced loose-fitting slip dresses, relaxed pantsuits, and, more recently, a shapeless halter named the “Carmichael Dress,” after one of Recho’s childhood heroes, the fictional Troy Carmichael from Spike Lee’s Crooklyn. A line of custom, hand-sewn shirts — one of which featured the word “niggas” in a signature act of rebellion — has made fans out of celebrities like Solange Knowles and Issa Rae.

As a label, OMONDI is staunchly “autobiographical,” explains Recho, who studied fashion design at Savannah College of Art and Design. From one collection to the next, she has drawn inspiration from her childhood as a Kenyan-American girl raised by a single father in the Midwest. These days, Recho — who has held design positions at Theory, Suno, and Calvin Klein — now considers herself “a designer and a critic.” Her candid and contemptuous feelings about fashion and the culture that surrounds it not only show up in the brand’s fresh and fanciful aesthetic but also in a recently launched podcast, The Cutting Room Floor. She is cheeky, brilliant, and here to stay.

Dress and trousers OMONDI, shoes RECHO'S OWN.

Dress and trousers OMONDI, shoes RECHO'S OWN.

How does your background inform your idea of fashion?

I was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, grew up in the Midwest, spent a lot of time in Kenya, but I also lived in Atlanta, which huge in my coming of age. Just the visuals: small gas stations, corn fields, films, and other things I saw will always be in my Rolodex of memories. And depending on the projects or certain moods, I pull at certain things to shape whatever story I’m telling. The last collection had to do directly with the relationship I had with the film Great Expectations as a kid. I brought the film into the world I also lived in, using green as the anchor.

Your play with color is a signature of the brand identity. Why are you drawn so strongly to color?

The color [of the brand] changes every year. There’s a point that it was pink, the year after that it was yellow — that’s just what I was feeling. So really the color is about my mood. Right now I’m seeing things through this terminal green color, which speaks to the internet but also Earth. Green is still what I’m feeling even though it’s been over a year.

That’s a very organic way of thinking about branding.

The aesthetic to me is the constant and everything else is the variable. There are certain things that will never change. Like, I don’t like lace, I’ve always liked big cuffs, I’ve always liked volume and flounce. The things I design are always shapeless, so those are things I will always communicate in the clothing.

I liken my company to the way that a recording artist would move. You would never ask Rihanna, “What’s your brand?” Yeah, it’s sex appeal, and it’s badassness, but she’s gonna grow: she went from red hair to blonde hair, short to long hair. So to ask someone as an artist, “What’s your brand?” is so stifling. I’m gonna change, and I need the customer to follow with me. My job, I see it as communicating with them and giving them a world they can live in and something they can hold onto.

Dresses by OMONDI.

Dresses by OMONDI.

Dress and trousers OMONDI.

Dress and trousers OMONDI.

The journey you are taking people on right now is one through dance. You often update your Instagram with stories from your ballet classes.

Ballet is a natural thing to reference because it was a huge part of my life for so long. The first thing I sewed was elastic onto my slippers. That was my first relationship with the needle and thread. And then I put [ballet] on ice because I was going to school and I was living in New York and I was on my grind. Recently I was like, Wait, why don’t I go back to doing things that make me genuinely happy that are a part of who I am? I’m a Pisces, so I’m romantic through and through and an idealist. Dance is an escape — it’s like being in a dream world. I like to bring that into the clothing and the content in the way it moves, so it feels like there’s an expression to it rather than it just being a cool T-shirt.

What is your vision of what art could be or should be?

Fashion has been so limited in terms of the way it’s interpreted. Like, technically the word “vogue” means what’s in style, what’s of the time now. So fashion doesn’t only mean clothing, it means what’s in the air and what’s in the zeitgeist. Dance is also part of culture, just like food is. It makes sense that I would involve my background in movement, and it makes sense that someone might do a concert instead of a fashion show, perhaps. My dream is to bring everyone to Lincoln Center to see a ballet designed by me, and that could be a totally different format of a fashion show. And it doesn’t have to be tutus, it could be real clothing, and that’s a totally different way of digesting the story and content because this format of a 15-minute show or an hourlong presentation is so narrow. There’s so many ways to explore how we can engage with clothing and storytelling.

Why did you start the podcast?

I started the podcast mainly for myself. But like, you and I, we’ll go to lunch and have conversations about fashion, collections we love, designers we hate, and how people got to where they are. And I thought, We cannot be the only people having these conversations. There’s no real Wendy Williams of fashion, there’s no ongoing conversation about current events. For example, what do we think about Jacquemus mens? What do we think about Virgil? Yeah, there’s thinkpieces here and there, but there’s nothing that’s really witty or places you can have real talk. I’m not in bed with advertisers, and I always thought, well, I wanna listen to a [show about] fashion. So I started The Cutting Room Floor because as a designer I thought, Should I really talk? Should I stay in the background and let other people talk? Can I be a designer and also be a critic?

“Fashion has been so limited in terms of the way it’s interpreted. Fashion doesn’t only mean clothing, it means what’s in the air and what’s in the zeitgeist. Dance is also part of culture, just like food is.” —Recho Omondi

Dress OMONDI.

Dress OMONDI.

Sometimes the best critics are the people making the art. There’s this thing, though, that runs up against this belief that artists of color, in an unfair system, should have a kind of radical solidarity. You have been critical of Virgil Abloh, even as some have said he got the culture on his back at Louis Vuitton. Why?

Because I love the fashion industry. I actually just had this conversation with Diet Prada. In order for me to love fashion, we have to set the bar high. We can’t just let everything slip. And he doesn’t get a pass from me just because he’s black. There’s a lot of other people who do amazing things, and there are a lot of black people who are disenfranchised and don’t get opportunities. I’d rather see the best black person win rather than just see a lame black person get it just because they’re black — like, this isn’t affirmative action! If you’re not good, you shouldn’t get awarded for it. I hold that standard for everybody — white, black, blue, or brown.

Some believe his work is a critique of fashion.

In the beginning yeah, I got it, it was very Margiela-inspired, very gimmicky, and it was kind of him playing the industry. But he’s taken that so far past the line, the joke’s not really funny anymore. It’s gotten to a point where it’s disrespectful. His vision is very lazy to me. I don’t really think he’s a great designer. I do think he’s a genius marketer. I mean, he would collab with Windex. There’s no discernment when it comes to that guy. And I get it, it’s kind of a joke on capitalism, but at the same time, some of us have been doing this for a really long time. It’s nothing against Virgil personally. I’ve met him a time or two, and he’s very present, very kind. But do I think he deserves the position that he’s in?

Is it about him biting other designers?

When it comes to biting, yes, nothing under the sun is original, but this is the first time in my time on Earth where I’ve ever seen where someone can literally knock something else off and it’s as equally respected as the original. In hip-hop, before, if you were to steal someone else’s style, they’d be like, “Get the fuck outta here. Try again.” And now, because of this scam culture, people are like, “Oh, get your bag.” People don’t have any kind of integrity. It’s like, yeah, borrow something, but your job if you borrow is to find a way to make it yours. Extend it. ‘Cause I’m not the first person to make a flouncy halter top dress. I’m not the first person to work with tulle. But what I’m doing with it is trying to bring it back to the street. I don’t see the point of any of this if you’re not reflecting the times and trying to move culture forward. There’s a Tom Ford quote that I love: “I know one day I’ll be irrelevant.”

Dress OMONDI.

Dress OMONDI.

Dress OMONDI.

Dress OMONDI.

Dress and trousers OMONDI.

Dress and trousers OMONDI.

Who have your influences been?

When [me and my sisters] were younger, if we ever said we were bored, we would get in trouble. My dad used to always say, “If you’re bored, you’re boring.” I have a lot of interests and influences. Dance is one of them: Mia Michaels, Justin Peck at the NYC Ballet. There’s photographers, filmmakers, even people in business. I love learning about Supreme or Jonny Johansson from Acne, who I think is brilliant. So in my own fashion space, there’s people I look up to.

My influences are very wide. I play piano and sometimes when I’m getting ready, I’ll play producers on YouTube, how they go about actually making their arrangements just as inspirations. Right now, having this garden, I spend a lot more time researching plants, which I never did before. Like, maybe next collection I’ll want to do a whole thing about the garden because I spent so much time here.

You and your sisters were raised by your father. How has that shaped you?

I didn’t grow up with my mother, so I think my ideas of what a woman is are based on characters I put together through books, movies, and real women I knew. I didn’t have a fixed standard. I didn’t see my mom cooking. I also didn’t see her working. I didn’t see her at all. Recently, I tweeted images of women who inspired my coming of age, and they were just different characters that I resonated with a lot. Harriet the Spy, she was so cool. A young girl who doesn’t care about having friends, who wants to write in her journal all day long. — that was me. Troy Carmichael from Crooklyn felt like she did what she wanted. Kirsten Dunst’s character in Crazy/Beautiful and her character in The Virgin Suicides. Just these smart young girls. Phoebe Philo, the way she was able to transform women into this Céline woman who was very demure and didn’t wear any makeup. Women are taught to be beautiful and desirable but here was this really chic girl — who’s the man who’s gonna fall in love with that girl?

Dress OMONDI, shoes RECHO'S OWN.

Dress OMONDI, shoes RECHO'S OWN.

Shirt and dress OMONDI

Shirt and dress OMONDI

I like that you made up the woman you wanted to be, which is really what happens with fashion — it’s all imagination. It’s like that saying: “You can buy clothes, but you can’t buy style.”

It’s all role-playing and character development. When you only have a few items in your closet and you can’t really afford to go shopping, so you’re like, “OK, I really like this top but I wore it last Friday, how can I wear it differently?” It’s incredible. That’s the sex appeal. The best part of designing and the fashion industry and what’s lost is the make-believe.

What do you envision for your future in fashion?

I want to do so many things, it’s stressful. All things aside, as problematic as he is, what Kanye West was really good for throughout his career was that clash of cultures I’m talking about. He helped bring high fashion to street culture. There is so much room to mash things up, like when I say I want to bring the fashion world to the theater. I want to do a collab with Repetto shoes and make them cute. I want to keep it rooted in grit and be able to, in some sense, speak to the underdog. I want to create a conversation. We’ve been idle enough — that’s how we got in this position to begin with in fashion. So I want to inspire people to speak out and do something more, because fashion is just the medium.

Shirt OMONDI.

Shirt OMONDI.