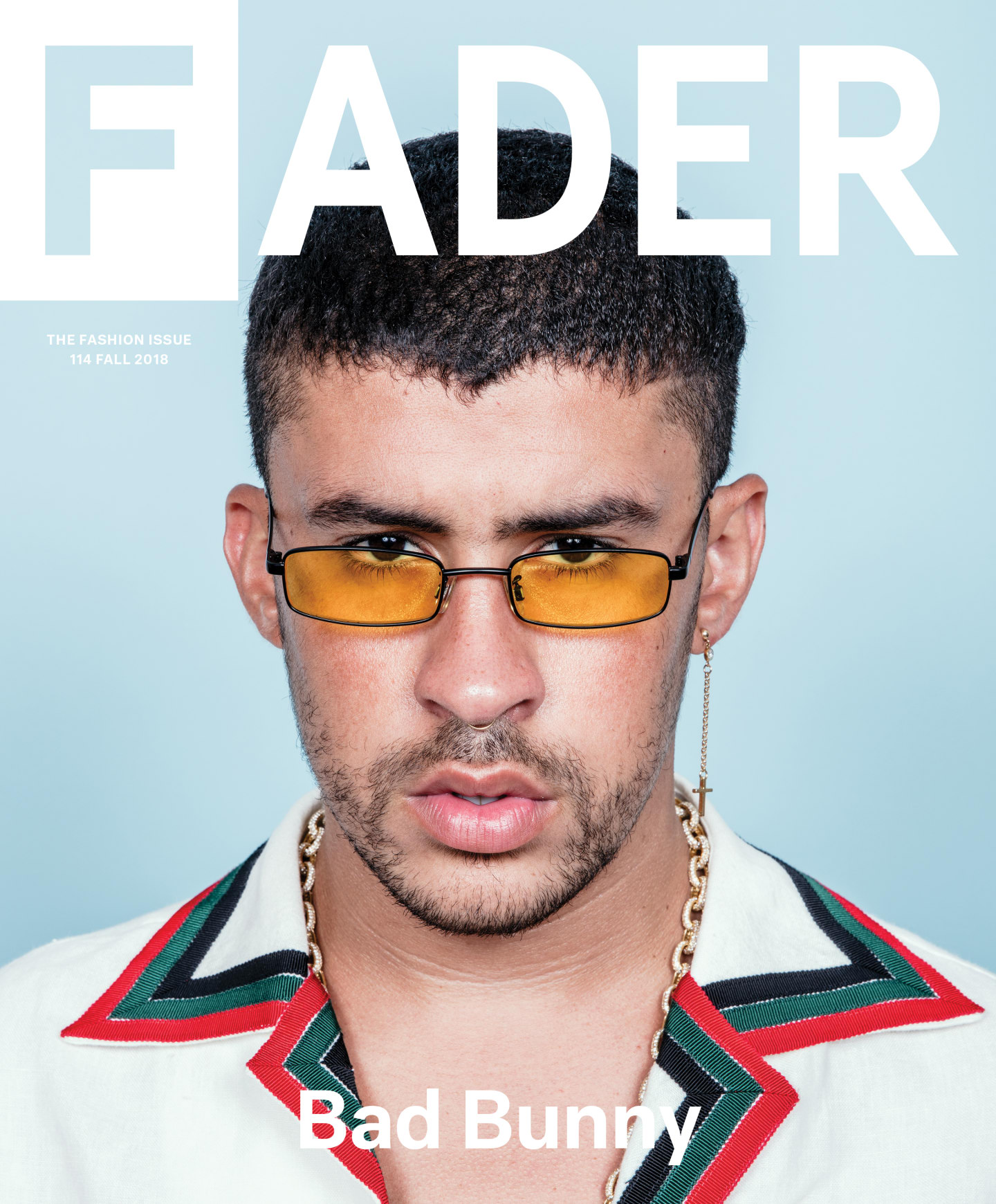

Shirt GUCCI, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Shirt GUCCI, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Additional Reporting by George Machado

The ice-blue infinity pool with the built-in barstools gently laps into a skyline so dreamy you can barely distinguish it from the ocean. The yard is built on a steep incline among a dense clutch of trees, where red ginger crops up wild. There’s a barrel near the pool, under a gazebo, of the sorts carted into corporate-sponsored parties to let people know who’s paying. It reads BACARDI-BACARDI-BACARDI, its logo a faded yellow.

This sprawling mansion, in a semi-gated community on el campo in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, has obviously been used before for lavish parties: there’s a serving station in the back where bartenders can set up and administer drinks. The house doesn’t even have an address — to find it, someone has to drop a pin. But its purpose right now is semi-permanent, and symbolic of a come-up. For years, growing up on the other side of Vega Baja in the tiny, close-knit neighborhood of Almirante Sur, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio and his friends would drive through this area, eyeing houses and dreaming. This was the one they liked best, and, by a stroke of luck, in June it came up on Airbnb, so they snatched it up, fulfilling some sort of impossible feat. There’s some money now, and a reason to use it.

The world knows Martínez Ocasio as the Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny, a 24-year-old Latin trap king with a distinctive, slackened baritone and a wardrobe full of tiny sunglasses and outrageously patterned, button-down shirts. This particular week, the first in July, “I Like It,” his Nuyorican party smash with Cardi B and J Balvin, has climbed triumphantly to No. 1 in the United States, and it’s widening his reach to an ever-growing English-speaking audience. Ask him about the milestone of having the top summer jam in the States and he casts down his eyes and grins, flashing teeth that belong in a Whitestrips commercial and revealing an unlikely facet of his offstage disposition: for someone in possession of such obvious charisma, el conejo is a shy one. “I think if I keep working in the way that I am, from the heart and from passion and with love, well, the fruits of that will keep coming,” he says in Spanish, his voice low but direct.

Shirt HOT TOPIC, shorts BAD BUNNY’S OWN, socks NIKE, sneakers JORDAN.

Shirt HOT TOPIC, shorts BAD BUNNY’S OWN, socks NIKE, sneakers JORDAN.

Bad Bunny has already witnessed abundance: in a little under two years, he has become an unequivocal superstar across Latin America and the diaspora. His irreverent, emotional, trumpet-like verses have been dominating on near-ubiquitous features with some of rap and reggaetón’s biggest names — Ozuna, Arcangel, Farruko, Alexis y Fido, Daddy Yankee, Nicki Minaj and, soon, Drake, who sings his verse in Spanish — and on his own songs, which notoriously started out as SoundCloud singles he uploaded while he was attending the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo as a communications student interested in radio, moonlighting as a bagger at the ECONO grocery store.

But he has yet to release a proper album, and that’s why Bad Bunny is here, in the wish-fulfillment Airbnb. Though his life has been a near-constant tour across Latin America, the U.S., and Europe, in July he has a rare month off that he’s calling his “vacation,” but it’s hardly that. Upstairs, away from the pool and a kitchen stocked with rum and pizza boxes and bags of Charms Blow Pops, he’s set up a makeshift studio where he’s hunkering down and trying to finish his first full-length, La Nueva Religión, an album he hopes will broaden his renown as well as his stylistic range.

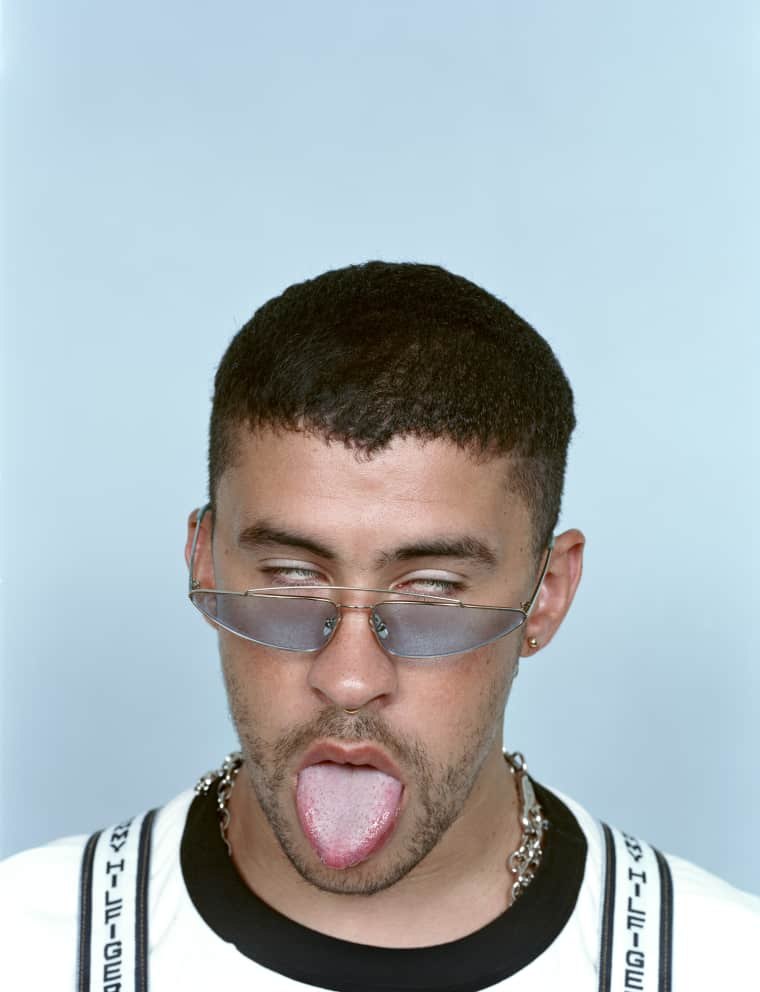

Shirt HOT TOPIC, overalls TOMMY HILFIGER VINTAGE, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Shirt HOT TOPIC, overalls TOMMY HILFIGER VINTAGE, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

“I know what it is to be a normal kid, I know what life is like for young people.” —Bad Bunny

Bad Bunny’s friends are crashing here too, a phalanx of young men and one woman, some of whom he’s known since middle school, all of whom he tries to be around as much as possible. There’s also his little brother, Bernie Martínez Ocasio, age 21, who has the same long, lanky body, and is traveling with Bad Bunny on his next tour to help. (Their youngest brother, Bysael, is 16 and still in school, but maybe not for long — he’s a baseball talent besting players years older than he is, and his next move is, ideally, training camp for the pros.) They all move as one unit, and Bad Bunny is reliant upon them to keep him grounded. Today in the mansion are eight young men, eating pastelitos de guayaba and chatting, and if it weren’t for the fact that their leader is upstairs painting his nails and choosing his looks for this photo shoot (he declines to work with stylists), you could mistake the place for a boarding school dorm. Its contents are quite dudeinous: wet towels on the floor in the bathroom; empties in the recycling; a bong on the counter; Un Nuevo Día, the Telemundo talk show, blaring at a low din on the television, even though no one’s watching it.

The familiar, average guyness is also, perhaps, a reflection of the crossroads where Bad Bunny now finds himself: a fairly regular twentysomething from a modest barrio in PR now learning to navigate astronomical fame, a fact that he and all his friends seem rather bewildered and blinkered by. (By way of explaining, his friend Jeddel Ashbiel Rosado recounts succinctly what it’s like for them to go to the club now: “Una foto… nah, trés fotos…” and so on.) The Martínez Ocasio familia, on the other side of Vega Baja, have been powerless since Hurricanes Irma and Maria: Their home is running on three generators, a fact that would ground anyone, but might have added gravity for Bad Bunny, who personally distributed water, food, and generators to his hometown last year. And so he is taking care to relish every minute of his success, even as he’s looking toward the promise of even more substantial wealth and fame.

Hat and jacket SUPREME, shirt VINTAGE, shorts BAD BUNNY'S OWN, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Hat and jacket SUPREME, shirt VINTAGE, shorts BAD BUNNY'S OWN, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

That’s where “Estamos Bien” comes in, the lush, triumphant trap single Bad Bunny released a few days before, which would eventually become another 2018 summer banger, hitting almost 100 million YouTube views in just a few weeks. Translating, basically, to “We Good,” it is truly a document of his appreciation for his new circumstances; though his voice naturally has a somewhat mournful quality due to its low weight, he perhaps has never sounded happier than when he sings “el dinero me llueve” — translated roughly, “the money is pouring” — but the song is much deeper than that, full of heart. It was, in fact, inspired by the very house in which he is staying, as was the self-directed video, which was mostly shot there and on the beach in Vega Baja. “It occured to me, when we got this house, that we should go buy a little camera,” he says. “At first my plans for it weren’t clear, but the idea for the song came to me and shooting the video with the camera came later. But we just got it to record the summer… It was just for us to remember this time.”

His friends are all in the video — that’s Jeddel in the backseat of the convertible, the cute, grinny fellow with the curly fade and yellow sunglasses — and it also very likely shows a young man in the twilight of normalcy before he becomes even bigger. He knows how he got here, clear in a verse sung an octave lower than the rest:

Aunque pa casa no ha llega’o la luz

Gracias a Dios porque tengo salud, eh, eh (amén)

La vida no tiene repetición

Después que mami me eche la bendición, yeh

When the video was done, Bad Bunny sent it to his mom over WhatsApp. She cried with pride, like she always does. “My mami and papi love my music,” he says. “They’re always listening to the radio waiting for one of my songs to come on. And when it does, they turn up the volume — and turn it back down when it’s over.

Benito Martínez Ocasio knew he wanted to be a singer from the age of 5. His father was a truck driver; his retired schoolteacher mother, like so many Latinx moms, encouraged his education in the ways of Jesús. “My mom is very religious — Catholic — and from a young age they brought me to the church. I’ve always liked to sing, [so] people in the church invited me to be part of the children’s choir.” He quit by the time he was 13 — “I said, ‘Nah, now I’m too old for this’” — but he’d already started experimenting with different styles and vocal tones, idolizing reggaetoneros on the radio like Daddy Yankee, as well as salseros like Héctor Lavoe, who are as essential to the cultural fabric of Puerto Rico as the humidity.

By the time he reached high school, he’d begun freestyling to entertain his classmates, little rhymes that dunked on people and made them laugh. “I knew he always had something special,” says DJ Orma, who has known Bad Bunny since 10th grade and now tours with him as his DJ. “He would always rhyme and even if it was just making fun of people, not everyone could do that. I always knew he had potential.”

Given time to overcome his initial bashfulness, Bad Bunny’s sharp sense of humor comes through in person, too, but underneath that is the all-encompassing drive of an artist. “I did those freestyles joking around,” he says rather modestly, “but only a few people knew I actually made tracks… [When] I started freestyling, everyone liked it and it was very funny, but in private I did it for real. Then people started to motivate me saying, ‘Why don’t you put out music, put it online, put it here, put it on Facebook, whatever whatever’ and I went, ‘No no no.’ But little by little, something was working in my mind and I said, ‘It’s true, I need to put something out.’”

Shirt VINTAGE, socks POLO, sneakers ADIDAS YEEZY 500, shorts BAD BUNNY'S OWN, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Shirt VINTAGE, socks POLO, sneakers ADIDAS YEEZY 500, shorts BAD BUNNY'S OWN, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Still in college, he began posting his tracks on SoundCloud. In 2016, he garnered a runaway hit with “Diles,” a simple, self-produced synth-trap track over which Bad Bunny’s voice drips honeyed, weeded, sensual nasty talk about dat ass. It caught the ear of DJ Luian, a reggaetonero with clout, connections, and a record label called Hear This Music; soon Bad Bunny was being heralded as the leading voice of the then-still-coagulating Latin trap genre, which recognizes and honors the outsized influence of Black Atlanta but also expresses cross-cultural fealty to español.

“Diles” was an early indicator of what is so compelling about Bad Bunny as an artist: though he tends to keep his flow and tone in the low bass-y zone, the versatility of his voice is truly impressive, and you can hear the history of his influences within it. He emotes like a salsero can, weepy and biting on a breakup track like “Soy Peor,” then cocksure and stunting on the weeded “Krippy Kush.” “My songs are always a mix of things I feel and think; things that I know are happening, things that have happened to friends, things that I know personally,” he says. “When it comes down to it, when I talk about me I’m not talking about a huge difference [from the general public], because I know what it is to be a normal kid, I know what life is like for young people.”

He posts Instagram videos of himself just dicking around and singing with the projection and depth of an opera singer; in another life he could also sing corridos with a Mexican banda. But Bad Bunny is self-aware enough that he understands what his talent can do. “Realistically speaking, yes, in two years I’ve turned into a star, and that tells me that I can do a lot,” he says. “If in two years I made myself a star, well, I expect that in two [more] I’ll be able to make a mark. My only goal here is that the people will always remember my music and that they enjoy my music 10 years, 20 years from now. That people have great memories of these songs, and that they won’t die. For real. I’m ready to make songs that don’t die.”

We’re sitting poolside on some wicker chairs when he says this, his brown eyes looking true. On cue, we hear a car in the distance blasting “Te Boté (Remix),” the savage breakup track packed with reggaetón superstars on which Bad Bunny’s verse dominates. He grins, points to his chest and proudly says, “Ese soy yo,” as if I don’t know — as if the track’s not playing in at least 437 places at once on the mainland and in Puerto Rico at any given moment.

Shirt VINTAGE, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY’S OWN.

Shirt VINTAGE, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY’S OWN.

He’s wearing a choker made of metal skulls, the kind one might find at a Hot Topic or even a Spencer Gifts circa 1997, and he’s paired it with an L.L.Bean logo T-shirt and a Supreme baseball jacket. The sleeves are leather but he seems not to be sweating. He smells hella good, too, like some fancy oil cologne they mix up fresh in a boutique scent store, but it’s not — it’s Unpredictable by Glenn Perri, something he picked up at The Mall of San Juan after the woman working in the perfume shop chased him down with it.

Nothing from the album is quite ready to be heard, he says, but he does agree to play two guide tracks from songs he’s working on that he thinks will challenge his fans, but not too much. He doesn’t want to freak anyone out, but he’s ready to get weird. He spends much of the day bleating, “I CAN’T FEEL MY FACE!” in English, transmuted into a soprano that sounds more “sped-up hook on a Juelz Santana single” than “The Weeknd.” He says, “Since childhood, I’ve been a clown. I’ve always liked being very funny or trying to make people laugh. It’s my original self.”

The first track he plays is mid-tempo, faster than anything he’s released before. The house music-alluding outro on “Estamos Bien” may have been intended to ready his fans for this because it sounds like ‘90s hip-house, but not in a corny or nostalgic way. The second track sounds like trap music as filtered through Marilyn Manson and The Matrix, and he says he wants Diplo to remix it. Both are wild.”In reality, I’m still working on this,” he says, not shyly but as a caveat that perhaps two unfinished tracks cued up on his iPhone aren’t even a sketch of what his debut album will sound like. But it’s something. “The reference tracks are really premature, but like, what I want for this record — the sounds, the vibe, the ambiance — are more of the things I like, more of me, more of what I am, and more of what I think is my generation, those born in the ’90s and the ’00s. From childhood, I’ve had a lot of goals of things that I want to do in music. When I release my record, there are going to be more songs to give people an understanding that my musical concept can be different — but also me.”

Shirt HOT TOPIC, overalls TOMMY HILFIGER VINTAGE, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Shirt HOT TOPIC, overalls TOMMY HILFIGER VINTAGE, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

“If in two years I made myself a star, well, I expect that in two [more] I’ll be able to make a mark.” —Bad Bunny

Bad Bunny’s personal style is refined and, like his music, spans a wide spectrum and is a little bit funny. In the “Krippy Kush” video, he wears a yellow windbreaker and Vans and spaced-out white sunglasses; he looks somewhere between Miami trap kid and the featured raver in a Happy Mondays video from 1991. In the clip for “I Like It,” he’s toned down for Cardi B, perhaps as a sign of respect, wearing a Puerto Rico baseball jersey and his signature cat-eye shades. More recently, he showed himself painting his fingernails a nice lavender in the “Estamos Bien” video, which led a horde of rather closed-minded commenters to speculate on his sexuality; he responded in a quite dirty tweet that as punishment he would impregnate those dudes’ wives and then make the husbands raise his children. “He doesn’t look like a regular trap artist right now, because he’s so hipster and so strange, and I think he’s being innovative,” says DJ Orma. “Back then [before his fame], he didn’t have the money to dress like this, but he had the ideas. Here in Vega Baja, almost nobody used to wear shorts above the knee, because people thought they were ‘gay’ or something. But in the skater community, that’s normal. He likes that skate swag.”

Among Bad Bunny’s millions of rabid fans are the traditionalists: those whose reception to the way he bucks tradition and rigidity in urbano music demonstrate the problem of changing hyper-machismo culture across the Americas (recall how some fans and fellow artists initially responded to A$AP Rocky and Young Thug wearing “dresses”). His retort to such conservativism is typically funny, nasty, and open — recall another Twitter thread in which he advocated for women to cease shaving their pubic hair as a form of freedom — and it’s precisely his unique sensibilities that seem to sail him through such close-mindedness without seeming to scathe him personally.

But as he seeks a more global fanbase, there’s another close-mindedness he may have to encounter. Though English-speaking audiences have seemingly become more open to music in Spanish — thanks largely to Luis Fonsi’s career-resurrecting 2017 mega-hit “Despacito” — rap en español has very infrequently engaged non-diasporic audiences in the English-speaking world (with a few exceptions, including a couple of reggaetón booms, if you’re counting). With the runaway popularity of “I Like It,” Bad Bunny’s already got a leg up — and his verse includes two bars that constitute the first time he has rapped publicly en inglés. He’s gradually bettering his English, although he makes it clear it’s the English-speaking world that needs to catch up to the Spanish-speaking one — the “Latino gang gang” — and not the other way around. “Sometimes I [forget] there are people that think I represent a town, a hood, a country. When I land [in Vega Baja], it feels super dope, but it’s also a responsibility — people expect the best from you. That’s why, every time, I try to be like, I am just me. I’m being me, and if what I am [is what] you like, well, good. If not, there will be someone else who will come and do that for y’all.”

Growing up, Bad Bunny spent a lot of time at the small skate park at the Complejo Deportivo Tortuguero in Vega Baja, and every year his crew takes a group photo there, near a halfpipe graffitied with a giant pink octopus. On a Thursday afternoon, they all decide to hop in a car caravan and drive over to take some more flicks. Bad Bunny stays in the car, straightening out his ‘fit, but everyone else unloads with the video camera and wanders around. There are two boys of about 17 sitting atop the halfpipe, looking glum, until Bunny gets out of the car, unmistakably tall and gangly, wearing Barbie-sized sunglasses with a red tint to them.

“¡Ay, conejo!” one of the kids exclaims, the sight of his fave rapper cutting through his teen malaise. Bad Bunny greets them generously and takes selfies with them. This is his home, and he remembers what it’s like to be a fan because he still is one: another dream he recently fulfilled, and perhaps an early instructor for his outsize persona and flamboyant sartorial instincts, was seeing some live WWE matches.

Bad Bunny’s fascination with wrestling started when he was a kid; ask about it, maybe after he’s smoked a blunt, and his face lights up. “Papi would watch wrestling all the time, when I was little like 5 or 6 years old, but I didn’t watch it, I would stay playing with cars and things. Like two years later, because of some cousins of mine, I started to watch it, and since then I’ve been a huge fan of WWE,” he says, animated. “I was huge fan of the wrestling here too, the IWA, and papa would take us to fights. So it’s always been a dream of mine to go to WrestleMania or at least a pay-per-view match. Because I hadn’t been to any, other than the small fights they had here, and it was now, thanks to God, that I could go to WrestleMania. Twice!”

Shirt GUCCI, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

Shirt GUCCI, necklace and sunglasses BAD BUNNY'S OWN.

For his “Chambea” video, in which he struts around in a floral Gucci suit and raps about being a hard-ass motherfucker, Bad Bunny hired Ric Flair to give him a rousing intro. Back at the house, he sits on a leather couch and pulls from a Phillie. “[Making the video], I kept saying, something’s missing. Then it occurred to me, like damn, let’s put a legendary wrestler in here. When I got to the video I was nervous—real nervous—and I didn’t know if he was gonna be humble or more like the persona. But he’s a super, super good dude and we became friends! He invited me to WrestleMania later, and he introduced me like a friend to all of the wrestlers. I met John Cena!”

“It’s like fulfilling your childhood dreams, not as an artist or career dreams, but your kid dreams. I’ve never felt jealous in my life, but the only time I’ve ever felt jealousy was when I saw the photo of Post Malone with The Undertaker. Brooo, I almost cried! You saw he did the choke-slam on him?”

It’s slightly surreal to see a burgeoning global superstar gush about another star the way millions of others would gush about him, but maybe that’s the crux of Bad Bunny, and why he’s resonated so strongly with so many people. He doesn’t take what he has for granted, and even strong weed can’t tamp down his emotions. Back at the Airbnb, as nighttime sets, there’s the knowledge that in one week, he’ll be back on tour — first across Europe, beginning in a small outdoor arena in Badajoz, Spain, through to the U.S. and Canada, and back home somewhere around November, a punishing four months on the road. Bad Bunny takes another hit off the Phillie and passes it to his boys; the air is thick and alive. Even with a celebratory tenor in the room, there’s a wistful sense, too, an expectation of the loneliness that accompanies fame. He’s having the time of his life, and he’s savoring it. He knows it might never be like this again.