Canadian hip-hop is so reputable in 2018 that eager fans across the globe look to it as a breeding ground for talent. This wasn’t always the case. You can thank Drake for drawing attention to Canada over the past decade, but the groundwork for the country’s hip-hop culture began long before he decided to be successful. Legends like Kardinal Offishall helped secure a spotlight that newer artists like Clairmont The Second are thriving in.

“A lot of times, people have no idea what happened pre-2009 or 2010,” rapper and executive Kardinal Offishall says of the Canadian hip-hop scene. “We went through so much behind closed doors, as a community, that people have no idea how difficult it was for a lot of us to even be taken seriously.”

As one of Canada’s most influential hip-hop artists, Kardinal Offishall began absorbing hip-hop culture as a kid growing up in Toronto’s Flemingdon Park section. Aspiring Canadian hip-hop artists had to do everything in their power to be part of the scene during the late 1980s and early 1990s, and Kardinal Offishall’s ambition took him from diligent underground artist to a major label deal with MCA Records in 2000. His breakthrough success, along with the hard work of contemporaries like Solitair, Choclair, Saukrates and Jully Black, paved the way for their successors. There’s no way Northern Bars would exist without their contributions to the scene.

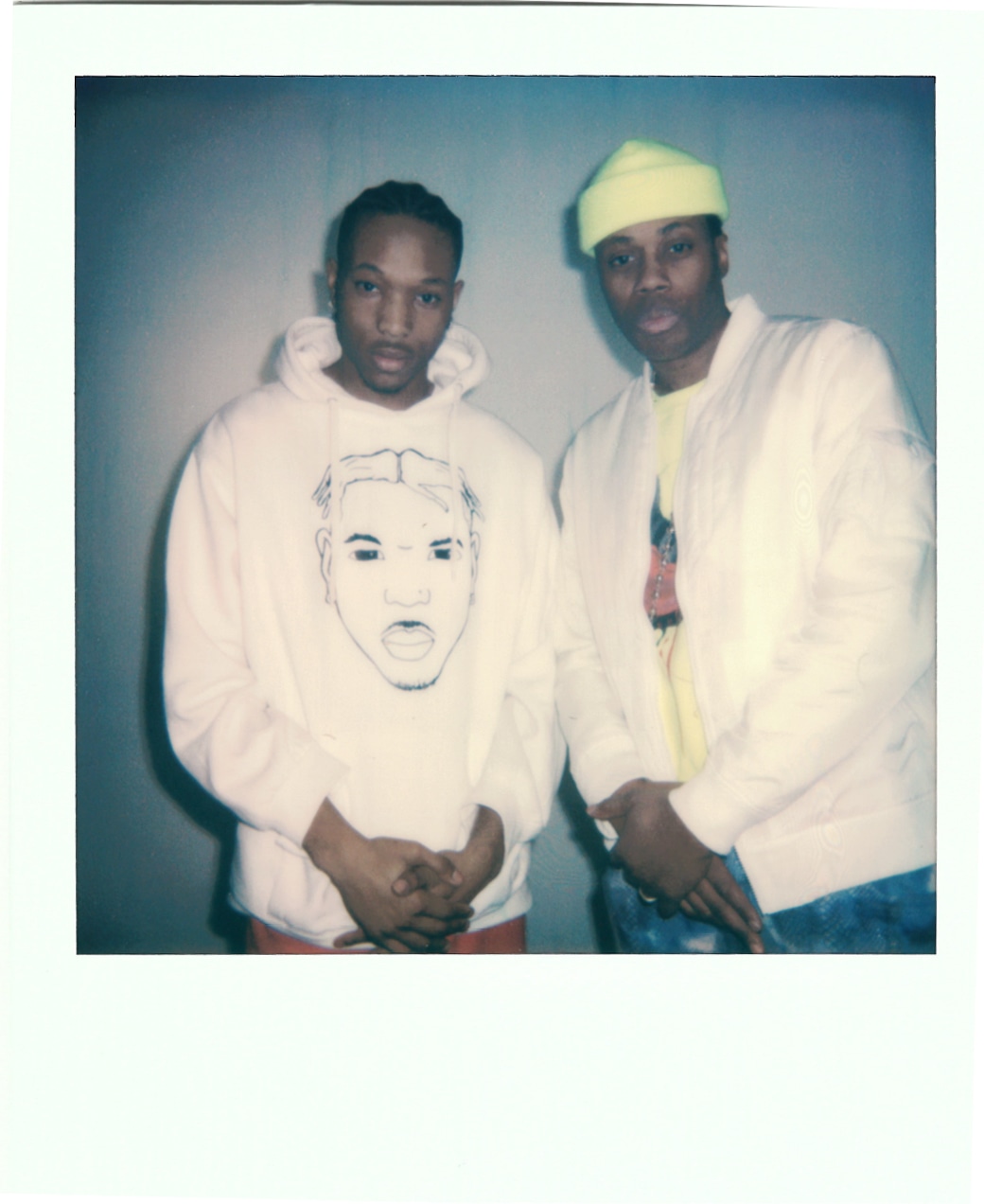

Kardinal Offishall & Clairmont The Second

Kardinal Offishall & Clairmont The Second

Spotify’s Northern Bars playlist features new music from Canadian hip-hop artists, exposing listeners to the latest from the likes of Prime Boys, Belly, Pressa, Clairmont The Second and more. Imbued with the work ethic of their predecessors and armed with a platform like Northern Bars, the new generation represents a new wave of rising Canadian artists taking over not only at home, but also on a global level.

With no spotlight awaiting them, Canadian rappers were forced to seek it out for themselves during the early ‘90s. Fortunately, many found encouragement during their formative years. When the provincial government created the Fresh Arts Program, Kardinal Offishall and other young rappers like Saukrates, Jully Black and the Baby Blue Fresh Crew honed their skills while being mentored by Orin Isaacs, Master T and DJ Mastermind. They learned the importance of having a having DIY attitude in the music industry and began starting their own record labels. Choclair and Lee “Day” Fredericks formed Knee Deep Records and Saukrates formed Capitol Hill Music, which Kardinal Offishall released his debut, Eye & I, on in 1997. That independent mentality was critical to the growth of Canada’s hip-hop scene.

“We realized we didn’t have an infrastructure, so we had to create our own,” Kardinal Offishall says. “We didn’t wait for anyone to give it to us.”

Canadian hip-hop artists were able to break down barriers and influence culture through international tours. Kardinal Offishall recalls being the opening act at the Roskilde Festival in Denmark. One day after he and Solitair thrilled a crowd of 10,000, they became the third to last act, right ahead of Dilated Peoples and The Roots. Traveling to showcase their skills on radio programs like Sway & King Tech’s Wake Up Show also helped Canadian rappers break down the barriers. By the early 2000s, Kardinal Offishal’s “Ol’ Time Killin’” was airing on BET’s Rap City, as was Choclair’s “Let’s Ride” after he signed to Priority Records. Soon, American hip-hop artists began showing their affinity for their Canadian counterparts. Kardinal Offishall says Lil Wayne recited his entire verse from Clipse’s “Grindin’” remix for him at the MTV Video Music Awards in 2005. Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg were fans of Choclair, and Saukrates worked with DJ Premier and Xzibit.

After Drake’s So Far Gone created a bidding war in 2009, the music industry began scouring Canada for talent. Tory Lanez became a household name in recent years. Now all eyes are on the abundance of Canadian rappers who can easily disseminate their music through the advent of the Internet. There’s Jazz Cartier, KILLY and EMP—who Kardinal Offishall signed to Universal Records—to name a few. And there’s Clairmont The Second, who also ran through the door Kardinal Offishall helped open and approaches music from a similar angle.

The rapper, whose single, “Tortoise,” is included on Spotify’s Northern Bars playlist, says his Christian upbringing fed his eccentricities and can be attributed to why his music differs from that of his peers. Establishing an appreciation for popular gospel artists like Kirk Franklin, Donnie McClurkin and Fred Hammond—from their vocal arrangements, to the chord progressions in their music—was very influential.

“The gospel music plays a part in how I produce,” he explains. “My siblings listening to R&B when I was super young plays a part, as well.”

Seeing things from the outside looking in shaped Clairmont The Second’s perspective, and after sifting through his musical influences, he developed his own identity and sound. His experience and interests may distinguish him from other Toronto rappers and the city’s prevailing sound, but he has taken a big cue from the Canadian rappers who preceded him: creating an impact through hard work.

“I want to influence hip-hop in a way where it’s not necessarily, the music, but it’s the work ethic,” he says. “People could look at me and say, ‘That guy works hard, I want to be like him.’ Also, he’s not just making music, he’s directing his music videos. He’s mixing his music. I want to be known as a legend from the city because of that.”

This hands-on approach is on full display on Clairmont The Second’s 2017 album, Lil Mont from the Ave. He made the album, an exploration of his coming of age on Toronto’s West side, after locking himself in his bedroom for a month and a half. And in the spirit of Canadian hip-hop’s forefathers, he took it upon himself to release it.

“I released it independently and it’s doing wonders right now,” he says.

Lil Mont from the Ave earned Clairmont The Second a Juno Award nomination this year, but his eyes are set on international acclaim for Canadian hip-hop as a whole. “Hip-hop coming out of Canada is in a good place because people are finally starting to take us seriously,” he says.