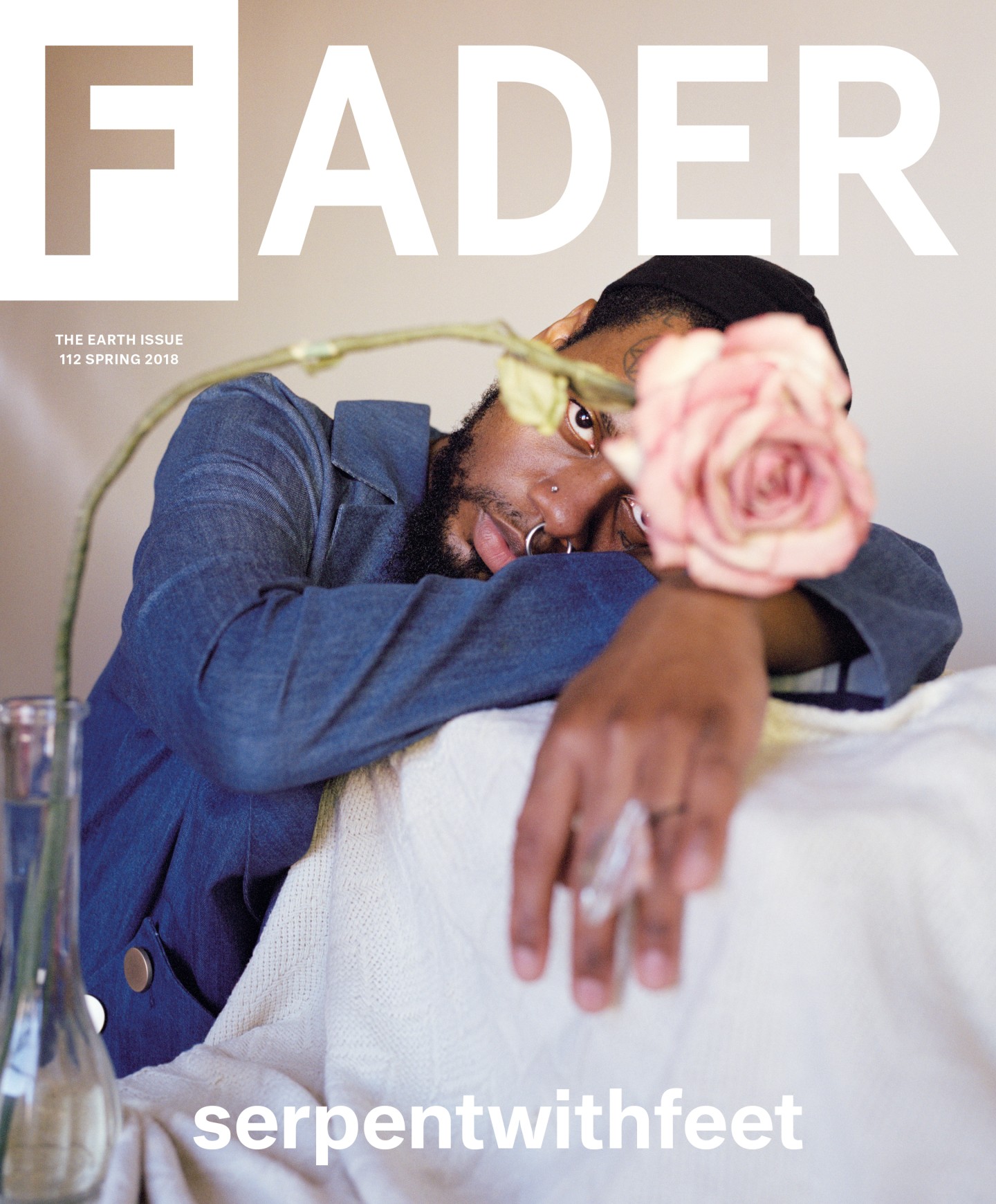

WOODHOUSE ARMY jacket, ring is artist's own.

WOODHOUSE ARMY jacket, ring is artist's own.

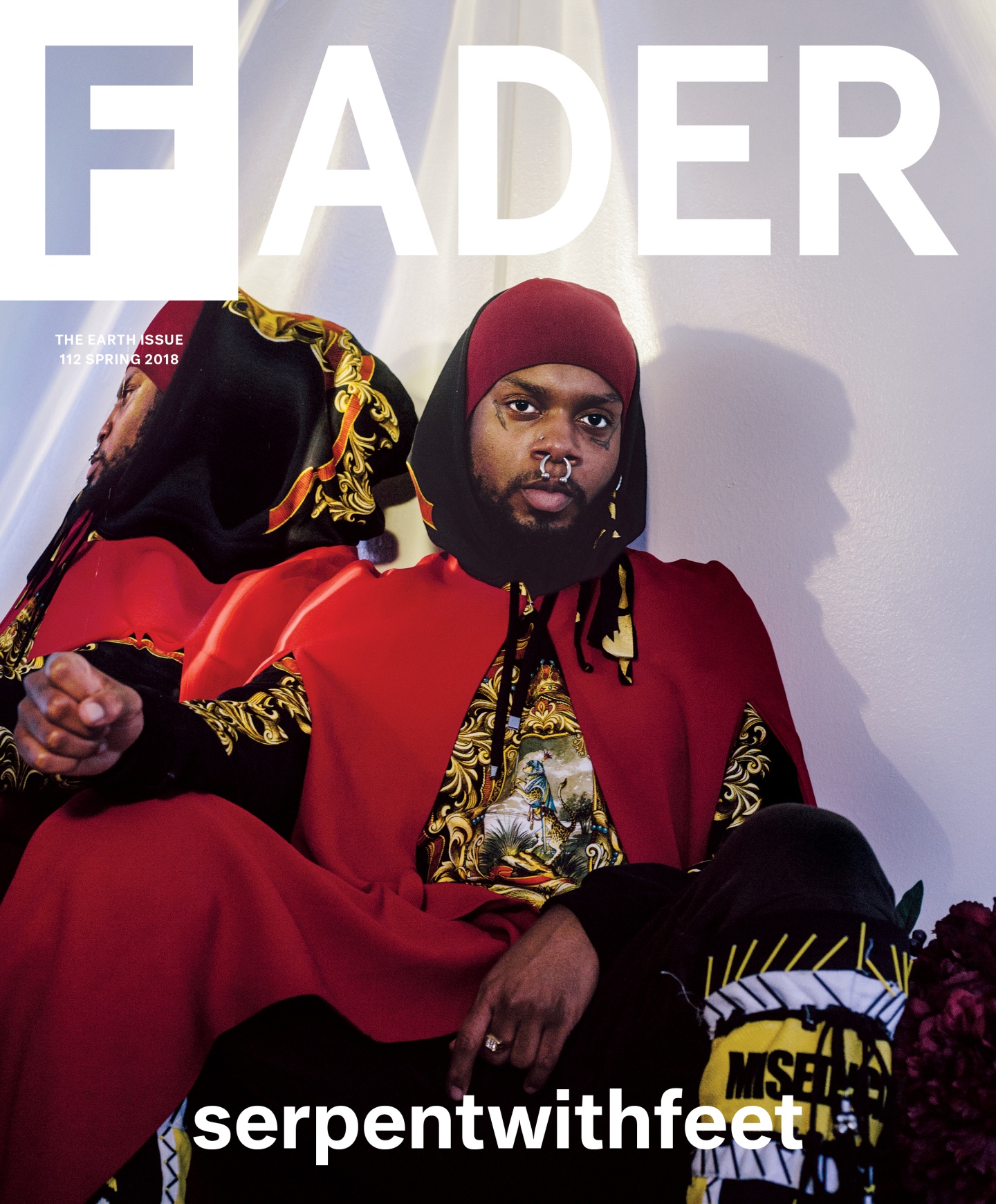

Buy a print copy of the serpentwithfeet issue of The FADER, and order posters of the two cover versions here and here.

The department store called Cookie’s is a neon labyrinth of toys, kiddy clothes, and reasonably priced school uniforms in every cut and color. Located in Brooklyn’s historically busy Fulton Mall, the multi-floor children’s emporium feels simultaneously retro and futuristic, like some flashy underworld marketplace from an ’80s science fiction movie. After a few wrong turns and a moment or two of sheer panic, I manage to follow the fluorescent signs up to the toy section, where the musician known as serpentwithfeet has already found three dolls he really wants to buy.

“They have a better selection of black dolls than a lot of other places,” explains the 29-year-old, whose given name is Josiah Wise. He looks cool and comfortable in lemon-lime Nikes and red trousers with giant pockets; his brother, a menswear tailor, gifted him the pants before a recent tour. When Wise gives me a hug, I note that his brown wool coat has an intense but comforting fragrance, one he later attributes to a homemade blend of scented oils. The hoop in his left ear is big and silver — a perfect match for the circular barbell he always wears through his septum.

Turns out, Wise collects all kinds of dolls and toys. Today he’s only allowing himself to purchase one — a creepy snow leopard that looks half-human, more like a character from an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical than a plush snuggle buddy. To make matters freakier, its stomach is stuffed with a quantity of tiny toy cubs.

All of Wise’s inanimate pals have names, personalities, needs. Some of his favorites include Down-low Lion, who is queer but on the DL about it, and Brandy, a Barbie-sized version of the legendary R&B singer, mass-produced by Mattel in the late 1990s. Later that day, she joins us for lunch at a soul food restaurant, nestled in the crook of Wise’s left arm, her little head barely peeking over the table. “She loves these red pants,” Wise says to me there, matter-of-factly, like he couldn’t get rid of her if he tried.

Brandy the doll went to every studio session for soil, the first full-length serpentwithfeet album, which comes out in June. The release is a collaboration between two labels: Secretly Canadian, whose roster includes big-deal indie acts like The War on Drugs, and Tri Angle, a tiny but undeniably influential experimental imprint.

In 2016, Tri Angle helped put out the first serpentwithfeet EP, blisters, an entrancing 20-minute mixture of ecclesiastical wails, R&B runs, and orchestral swells. Across its five tracks, dour production by the British electronic artist The Haxan Cloak helped build tension. But it was Wise’s singing voice — technical, flexible, full of pain and desire — that really brought the drama.

While the EP resonated with fans of dazzling vocal work and avant-garde textures, Wise hopes his new music will reach more ears. A recent collaboration with Björk (“I literally fell off my bed when she asked”) and the complex, urgent-feeling love songs on soil should certainly help things along. “I recently said something to myself,” Wise recounts when I first ask about the album, which, in a lot of ways, finds him moving forward by looking back. “My roots are catching up with me.”

RALPH LAUREN PURPLE LABEL jacket, HILDUR YEOMAN necklace, artist's own bag and pants.

RALPH LAUREN PURPLE LABEL jacket, HILDUR YEOMAN necklace, artist's own bag and pants.

Those roots stretch to northeast Baltimore, where Wise grew up in a middle-class black neighborhood with a bookseller father and a stay-at-home mom. His brother, a lifelong entrepreneur 10 years his senior, chaperoned school trips and chauffeured Wise around the city. “At the time it seemed difficult, like there was a lot going on,” he remembers of his childhood. “It felt cluttered, and I never got a chance to rest. I was always on guard.”

He was raised religious, and he spent a lot of time hanging around his dad’s Christian bookstore. “I loved it, but now I’m like, I really had the Moses version of Pac-Man.” Wise was what his family would describe as a “moody” kid, often retreating to his bedroom for long solitary stretches, a ritual known around the house as “Josiah going to his dark place.” He was also preternaturally fascinated with death. “When I was in second grade, my parents were already talking about what colleges I would go to,” he remembers. “I was always thinking, It would be so nice to study creepy things. But I never said it out loud.”

At 6, Wise joined the choir at his family’s Pentecostal non-denominational church. It was a big church with a couple of thousand members and two basketball courts. “I loved the grandeur of it,” Wise says. He also really loved to sing, an affinity he may have inherited from his mother, a one-time choir director who Wise says “has a beautiful voice.” Though he was part of the more traditional group that sang during the service, Wise has strong memories of the less structured prayer and worship singers. “I remember my best friend and I just dancing,” he tells me. “I was very excited about church as a kid. That was my world.”

WOODHOUSE ARMY jacket, DONNIE MAC jeans worn as scarf, artist's own shirt.

WOODHOUSE ARMY jacket, DONNIE MAC jeans worn as scarf, artist's own shirt.

Though both of his parents were tough, it was his father with whom Wise regularly clashed. “My mom was always trying to get me to be nicer to my dad, and I just wasn’t, because I saw what was going on.” He felt angered by the way gender roles were policed — in his neighborhood, but especially at home. “My father wasn’t interested in my mom working,” Wise says. “I think the men around me did the best they could, but by and large I saw them being very callous. Like, ‘if I can’t be great, if the system is fucking me up, then I’m definitely going to fuck you up.’”

That kind of energy can be suffocating, especially for a closeted queer kid who likes singing and the macabre. “Everybody knew I was gay,” Wise remembers. “There was a part of me that wanted to be more vocal about it, but I didn’t have the courage to.” By high school he’d figured out how to blend in, how to avoid drawing any unwanted attention. “If you have too strong of opinions or if you’re just too, T-O-O, you can end up in a lot of trouble with your peers, the teachers, whomever,” he tells me. “I knew how to be non-confrontational in order to survive.”

After graduation, Wise left Maryland to study music at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. “I was convinced the only thing that mattered was classical music, specifically European classical music,” he explains of his art school days. “I was that boy.” Even while his friends and teachers encouraged him to explore different styles that seemed to come naturally to him, like R&B, he was dead-set on finding success as a classical singer. “I know they were trying to help me, but I was like, That’s not what I want to do.” He also started volunteering with Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, which led him to 8-year-old Kareem and his 2-year-old brother, Steve — both of whom Wise is still close with now, a decade later. “Those are the boys of my heart,” he tells me, sounding something like a proud parent.

In 2008, his own father died from complications related to diabetes. “I think he wanted to go,” Wise says today. “The doctor would be like, ‘If you stop eating ice cream and corn syrup and 25 cakes, you’ll be fine,’ but he wouldn’t.” The aftermath was difficult, especially because the family had suddenly lost its primary breadwinner. “I wept because I was sad for my family,” Wise says. “Like, you didn’t let my mom work and now we’re broke. For me, that’s careless and irresponsible and I can’t fuck with it.”

When college ended, Wise was rejected by the graduate-level conservatories he desperately longed to attend. “That was heartbreaking,” he remembers. He explored Paris for a few months, before settling in New York City in 2013, where he held jobs in retail, tutored kids, and worked hard on music, determined to find a sound that stuck, a sound of his own. “I knew that I had to make music my career,” he remembers. “I don’t have a backup plan, I don’t have a safety net at home — something has to work.”

After losing one retail job, Wise spent most of 2014 unemployed, broke, and without a stable living situation. He crashed with four, five, six other people in shared single rooms on the fringes of his adopted home city: the top of the Bronx, the edge of Queens, deep Brooklyn. He hit something resembling rock bottom on a gray day when the leaseholder unexpectedly kicked him out of one said room, even though Wise had paid his agreed-upon rent. “When it’s like a hotel, people can do what they want,” he tells me. He was forced to load everything he owned onto the subway, which he rode to a friend’s place; it poured down rain the whole time.

Amid these setbacks, Wise kept on making songs. He recorded one that summer that would, in certain ways, go on to change his life. Called “Curiosity of Other Men,” it found Wise singing about a crush over a Tchaikovsky sample, which itself interpolates an aria, or a long solo, from his Russian opera called Eugene Onegin. “I was like, What would it be like to have some classical [elements], but then also do my little church-boy stuff?” he remembers of that long-time-coming creative jumpstart. “I enjoy things that are nebulous.”

“Curiosity” wasn’t just the first time he experimented with fusing genres, but also the first time Wise was able to sing about his desire in a way that felt one hundred percent honest. “All the stuff before was me trying to be fake deep, using words that didn’t fit my mouth — just, like, doing a whole lot,” he recalls. “I wanted to get to the bottom of myself: I love men, I love love, I want to talk about this really pointedly.” On Soundcloud, the track got more attention than anything he’d posted before it.

He started feeling bolder and more comfortable in his skin, growth he credits to his period of creative and financial uncertainty. “I don’t think my story is an anomaly, but it pushed me,” he says. It was around then that he shaved his eyebrows, pierced his septum, and started getting tattoos; today he has several on his face and head: a blade, an inverted pentacle, the words “heaven” and “suicide” — permanent evidence of a lifelong interest in the occult.

LAUREL DEWITT jacket, BOBBY DAY pants, LARUCCI ring, artist's own sleeve.

LAUREL DEWITT jacket, BOBBY DAY pants, LARUCCI ring, artist's own sleeve.

“He is, vocally, one of the most emotionally generous singers. I just find [his music] so moist and vibrant to listen to.” — Björk

“I felt like I was in my body for the first time,” Wise remembers. “I felt that I was walking out of the house and I wasn’t apologizing for walking out of the house.” For the first time, he also started to find people that understood him, that were like him, a community that he hadn’t realized was there before.

After making other songs in a similar vein to “Curiosity of Other Men,” Wise’s music found its way to Robin Carolan, the taste-making founder of Tri Angle, in 2015. They exchanged a few tweets, then met for drinks at Happyfun Hideaway, a dive bar under the M train in Bushwick, the type of kitschy outcast refuge that’s becoming increasingly rare in contemporary New York. “I’ll never forget, one of the first things he asked me was, ‘What do you want? How big do you want to be?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know who my music will reach, but I am ambitious. I want to do the most that we can do.’” By the following day, Carolan was officially his manager.

The blisters EP, released in September of 2016, was a quiet and somewhat mysterious introduction to the serpentwithfeet universe; if 2016 was a party, Wise skipped the big grand entrance, choosing instead to float playfully around the function like a specter. But the music had a way of lingering with you and seemed to strike a chord with other creators, including the Billboard-charting R&B singer Ty Dolla $ign, who tweeted enthusiastically about the project, and Björk, whose interest in blurring the lines between the cerebral and the sentimental predates Wise’s experimentation by a couple of decades.

“He is, vocally, one of the most emotionally generous singers,” Björk says over email. She says she admires the “balanced idiosyncratic pagan spiritual angle” to his work — an aesthetic she describes as “optimistic goth.” The two first met through Carolan, and Wise had the chance to sing in front of her, one on one, before the EP’s official release. “His lyrics are incredibly personal,” Björk adds. “I just find [his music] so moist and vibrant to listen to.”

The EP’s title track has served as a blueprint of sorts for all the music that Wise has made since. “I use ‘blisters’ as my arrow,” Wise says. “I was really proud of that particular song.” Anyone would be — it’s an epic tearjerker with IMAX strings, handclaps and soulful hums, and visceral lyrics. Written while Wise was “violently single,” it’s a good example of the way he finds beauty in unconventional settings. “Pretend the floors cracking in the shape of our names is not a big deal,” he sings with fluttery, playful diction. “Pretend the dying flowers growing towards us is not a big deal.” It’s over the top and, at the same time, almost too real.

VALENTINO cape, DOLCE & GABBANA hoodie, artist's own beanie.

VALENTINO cape, DOLCE & GABBANA hoodie, artist's own beanie.

I’ve lived in New York for five years and I'd never taken the A train all the way to the northernmost end. I’d never climbed the steep, hook-shaped walkway that winds along the perimeter of Fort Tyron Park. I’d never paused at the top, where the path overlooks a dense plot of maple trees and the Hudson, where it doesn’t feel like Manhattan anymore because it literally almost isn’t. At least, I’d never done any of those things until one bone-chilling afternoon in January, when I agreed to meet Wise on 207th Street.

These days Wise lives in Brooklyn, off the L train. But he still has a penchant for New York’s far-flung outskirts, places with a bit less friction. “I come up here often, for hours, when I need space,” he says when we get up to the lookout spot. Out of breath, I notice then how much better prepared for the cold Wise is, with a knit scarf and gold gloves and baggy yellow pants that you could probably wear skiing. “I even come when the sun’s down. There’s still folks here, so I feel comfortable enough to come and just think.”

We walk for a little, along the stone-walled perimeter of the medieval-looking castle known as The Cloisters. We pass a spot where some melted snow has turned solid mid-runoff, now a jagged crystal waterfall frozen in time. “That reminds me of how an Enya song sounds,” Wise says, laughing.

RALPH LAUREN PURPLE LABEL jacket.

RALPH LAUREN PURPLE LABEL jacket.

A week earlier, he’d traveled back to Baltimore to celebrate Christmas. “I didn’t think of my neighborhood as beautiful before I left, but when I went back home this time, I was like, ‘Mom, this block is so cute,’” he says. “It’s black families doing their normal shit — I can hear birds chirping, I can hear individual children’s laughter, I can hear conversations.”

He’s actually been revisiting a bunch of time-worn memories: elementary school friends, singing in church, watching Sister Sister and Zoom, that time in the mid-’90s when Baltimore got hit with a blizzard and his mom single-handedly built a perfect igloo for all the kids on the block to enjoy. “I am ready to really appraise what I have learned so far, specifically my first 18 years living in Baltimore under my parents — how were they raised, why were they the way there were,” he explains.

His animosity toward his father seems a bit easier to reconcile with some distance, too. “I feel like there are so many men that never get a chance to be little boys,” he says. “When I think about my dad, I think about somebody who never got to carry that little boy with them. When you constantly rob yourself of that, how do you treat other people, how do you treat yourself? I wasn’t able to love him when he was alive — I couldn’t, I really couldn’t. But when he died I was like, OK, now I can talk to you.”

This new regard — for the fabric that he comes from, for the messy and indefinite concept known as “home” — manifests in several ways on his new album, soil. The title speaks to the idea of roots, but so do the words he sings and the way the music actually sounds. “Different guys told me that I dig a lot,” Wise says. “I dig and I dig and I dig. It made me think a lot about my mom, about the black women that raised me, and how they always had another question. You know what I mean? They always had another question.”

Wise worked with four producers this time: Lil B and A$AP Rocky collaborator Clams Casino; a Boston producer called mmph; Grammy-winning Adele collaborator Paul Epworth; and, most significantly, Tri Angle artist Katie Gately, whose inventive sound design helped bring Wise’s deeply personal vision to life. On “Whisper,” the record’s lovesick opener, a sample of an industrial-strength washing machine crescendos like a slow-moving steam train, vividly recalling sonic textures from the golden age of Motown quartets. “Love says you are not too much,” Wise sings. “There’s space for you in this home.”

Wise tells me he put literally everything he had into the album. “I want it to feel like it was crafted by somebody,” Wise says. “I’m very tacky, very raggedy. I want people to feel that. Oh, you can tell he did that himself.” There is still a loftiness to soil, but that DIY spirit also led to bigger hooks and more obvious grooves — sounds he says pay tribute to the dance music that permeated his youth in Baltimore, from the church to the club. “At one point I listened to a lot of classical music and sinuous stuff,” Wise says. “Now I’m like, is it Brandy? Is it Beyoncé? I need to find a snap. I need to catch the beat.”

VALENTINO cape, DOLCE & GABBANA hoodie, artist's own beanie.

VALENTINO cape, DOLCE & GABBANA hoodie, artist's own beanie.

“I’m very tacky, very raggedy. I want people to feel that. Oh, you can tell he did that himself.” —serpentwithfeet

Wise’s favorite of the new songs is called “Cherubim,” the plural of cherub, the angel whose job is to protect paradise. On the track — a gorgeously layered, in-your-face spin on a classic gospel foot-stomper — Wise’s vibrato shimmers over a looped deep breath and thunderstorm drums. “I — get — to — devote my life to him,” goes its responsorial-like mantra, on which Wise’s voice is multi-tracked and booming. You could easily imagine it being chanted in unison by a spellbound audience, or even a 2,000-person congregation.

“There was a time that I wasn’t using any of the words I learned in church. I was like, That language is oppressive.” Now he doesn’t just use that inherited vocabulary, he actually seems to subvert it, singing gay love songs about caring for a man, about loving him, in a way that he used to sing about loving God. Wise understands that acknowledging his history can help him make art that’s more unique, and in turn, more powerful. “I don’t have to be brand new every time,” he says. “I get to be all of myself.”

Wise officially came out to his family a few years ago. “I had to stop thinking of myself as marginal,” Wise remembers. “I had to stop thinking of my sexual interests as something that was mutable, something I could change. I think that’s an overwhelming sentiment: that gay people are gay because they couldn’t take a cab so they took a train and got gay on the train, like, If we give them cars they won’t be gay.” He told them only once he felt confident, in his language around the topic and in his wants and needs. “It changed the way people interacted with me,” he remembers. “But it’s good, it’s all good — my family loves me, and I love them.”

In his 2012 essay, “The Children and Their Secret Closet,” the music producer and historian Anthony Heilbut writes that he “long ago concluded that gospel music was the blues of gay men and lesbians.” He shows how the homophobia of the modern church is profoundly hypocritical, how the “punks” and “sissies” are actually responsible for much of the musical culture those communities hold sacred.

When Heilbut writes “with eyes shut, gay men have danced steps that would both anticipate and transcend the partiers in any club,” I think of a young Josiah, sullen and sensitive and always a little restless, dancing during Prayer and Worship, finally, for a few songs at a time, at peace. I think of the music he makes now as serpentwithfeet, of the way it makes you want to close your eyes and move and let every other little thing fall away.

At one point, I ask him if his fascination with taking care of dolls has anything to do with his recent reappraisal of his past, with his newfound appreciation for the domestic existence he ran away from. “All of it,” he says, nodding. “I’m always thinking, What do I want for myself, for my life? Before, it was always simple — just some big open space, some windows, and me. Getting closer to my little brothers in Philadelphia, it made me think less about I and more about we. They say, ‘How you doing big bro?’ And I love that.”

When our toes and faces go numb, Wise and I ride the subway downtown. Above ground at Canal Street, he spots a display of black girl dolls, each small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. “This is so unexpected,” he says, flustered-sounding. He buys two of them — they’re sisters, he decides, so it’d be plain cruel to split them up. Hours later, when I’m scrolling through Instagram on my phone, I’ll learn their names via a video uploaded by serpentwithfeet himself: one is Lucky, the other is Dae.

Assistant stylist: Martin Tordby