In 2003, Diddy enlisted Kelis for an experiment: a Euro club track called “Let’s Get Ill.” Before EDM penetrated America and before hip-hop and R&B became the polyglot genres they are today, Diddy and Kelis channeled the spirit and sound of raving in Ibiza on a single that’s mostly been lost to time. This was two years before Madonna put out Confessions On A Dancefloor, four years before Britney Spears’s Blackout, and six years before David Guetta templated pop-dance crossovers with his Kelly Rowland collaboration “When Love Takes Over” and the hit album One Love. “Let’s Get Ill,” which became moderately successful on the European club circuit thanks to a Deep Dish remix, was all smoke machines, sirens, and lasers. And on it, Kelis, who’d briefly lived in London after the success of her 1999 album Kaleidoscope, delivers a typically idiosyncratic hook, channeling the robotics of Cybotron instead of Ultra Naté club diva.

“Let’s Get Ill” is ahead of its time, indicative of Kelis’s distinct genre agnosticism and the seed of her relationship with dance music, which was fully realized on the 2010 album Flesh Tone. Kelis has always stood apart as something of an experimentalist throughout her nearly two decade career. Her 1999 hardcore-inspired R&B debut single, “Caught Out There,” didn’t mince this: it was a generational revelation. On it, she’s Rihanna rapping before Rihanna rapped, and in the video she’s an intersectional, anti-slut shaming advocate who Takes Back the Night.

The four albums Kelis released prior to Flesh Tone supported the popular narrative of her as one of R&B’s then-rare weirdos; a punky womanist who brought The Neptunes’s off-kilter production to life with heartfelt, and sometimes cynical, tracks about love and relationships. With the exception of 2006’s Kelis Was Here, these albums all performed better in the U.K. than the U.S. (2001's Wanderland didn't even get a Stateside release.)

So it makes sense then, that for her fifth record, which was recorded while she was pregnant and released after the dissolution of her widely publicized marriage to Nas, Kelis would look to a market that had sustained her, and find creative catharsis on the dancefloor. “There’s a difference between being a pop star and an artist,” she told The Guardian in 2010, “Pop stars have to be perfect all the time; an artist is allowed, on occasion, to suck. I’m not trying to please the masses. It’s not going to happen, so I don’t try.”

On Flesh Tone, Kelis isn’t a music industry casualty or a scorned ex-wife; she’s Knight’s mom, and a visionary.

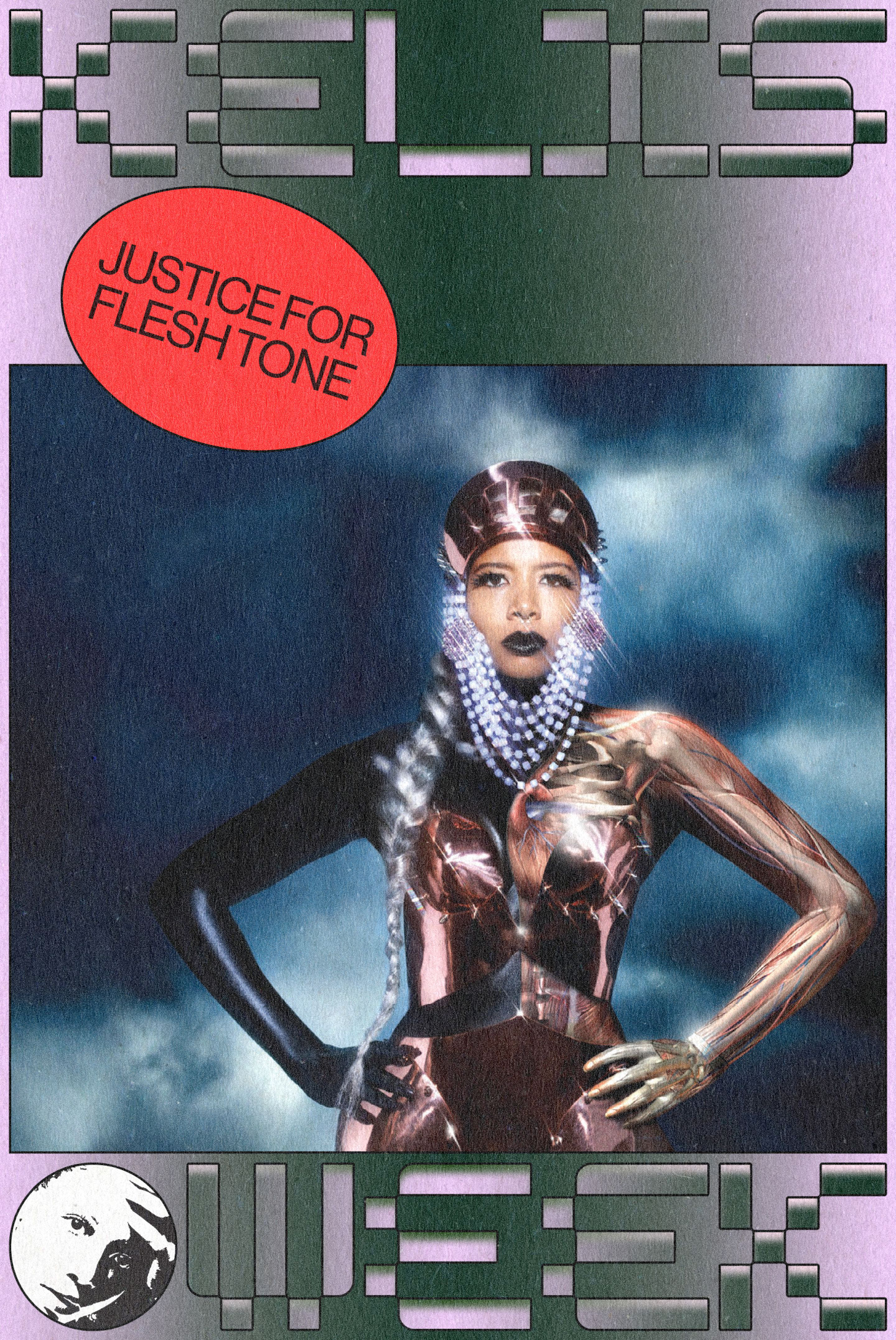

Flesh Tone is the album where she went even more ‘left,’ but it stands next to Kaleidoscope as one of her most consistent releases. Executive produced by will.i.am., with production by David Guetta, Boys Noize, Tocadisco, and Benny Benassi — names now synonymous with a kind of Eurodance cheese — Flesh Tone might feel sonically dated to some, like many cultural products that are ahead of their time. Her ‘unexpectedness’ was expectedly ballsy, and the production holds up to this day because it’s accompanied by some of Kelis’s most intimate lyrics.

“Didn’t think I needed you, never seemed to, but I’m living proof/ Now I’m brand new, rename me, baby claim me, I’ve been changed see,” she sings huskily over four-on-the-floor untz of Flesh Tone’s second single, “Fourth Of July (Fireworks). Later on “Acapella,” a tightly-wound Guetta fist pumper, she’s transcendent: “It’s just me surviving alone/ Before you, my whole life was acapella.” And on “Brave,” she’s revelatory: “It wasn’t that way in the beginning/ It was ‘this way,’ it was ‘kiss me,’ come kick me and dis me, I had to give it up/ It was crazy, had a baby, he’s amazing, he saved me/ I was super cool, but now I’m super strong.”

Flesh Tone is also the album where, after years of being locked in creative and personal battles with male collaborators, male-run labels, and male partners, Kelis was finally able to take control of her own narrative. “I recorded most of the album when I was pregnant,” she said in an interview with Idolator at the end of 2009, “Being pregnant, like full of life, is really kind of the answer. I was full of life. That was something I couldn’t ignore.”

Motherhood is one of many gendered experiences that prove women are not more fragile, but indeed more powerful, than men, and Kelis channeled that energy into making an incredibly defiant album that allowed her to step out from under the shadow of The Neptunes and Nas. (Not enough is said about how Kelis helped crystallize Pharrell’s now-renowned pop ambitions.) On Flesh Tone, Kelis isn’t a music industry casualty or a scorned ex-wife; she’s Knight’s mom, and a visionary.

Commercial artists like Pink, Fergie, Madonna, and Adele are praised for marketing middling records around their identities as moms. But black artists like Kelis, Erykah Badu, Georgia Anne Muldrow, Beyoncé, Lauryn Hill, and Ciara don’t get enough credit for not just chronicling the experience of child-rearing but making some of pop’s best music as a result. Motherhood, from the perspective of these artists, isn’t creative complacency sold as twinkling ballads and lullabies; it poses a new creative challenge.

Kelis is also a different kind of mother; she’s birthed a new generation of post-genre musicians who look to her risk-taking career as inspiration for their own. Last month at Camp Flog Gnaw in Los Angeles, informed by the tastes of Tyler, The Creator and his Odd Future affiliates, Kelis performed a brisk, hit-spanning set that bumped up against disco, dancehall, and EDM, as the sun dipped behind darkness on a side stage (The next day Kid Cudi, whose fame was cemented with a pulsing Crookers remix, headlined the main stage) “I have 20 years in this, and it’s crazy to stand here, after standing in crowds that look nothing like this, wondering how a girl from Harlem can do this,” she told the crowd. “Now I look at a crowd of people that look like me.”