These young Londoners are fighting to make sure you don’t forget about Grenfell Tower

Local residents and volunteers explain how their community has strengthened after the tragedy, and why they’ve made a documentary about it.

Volunteers (l-r) Shona Harvey and Adrianne McKenzie, September 26 2017.

Volunteers (l-r) Shona Harvey and Adrianne McKenzie, September 26 2017.

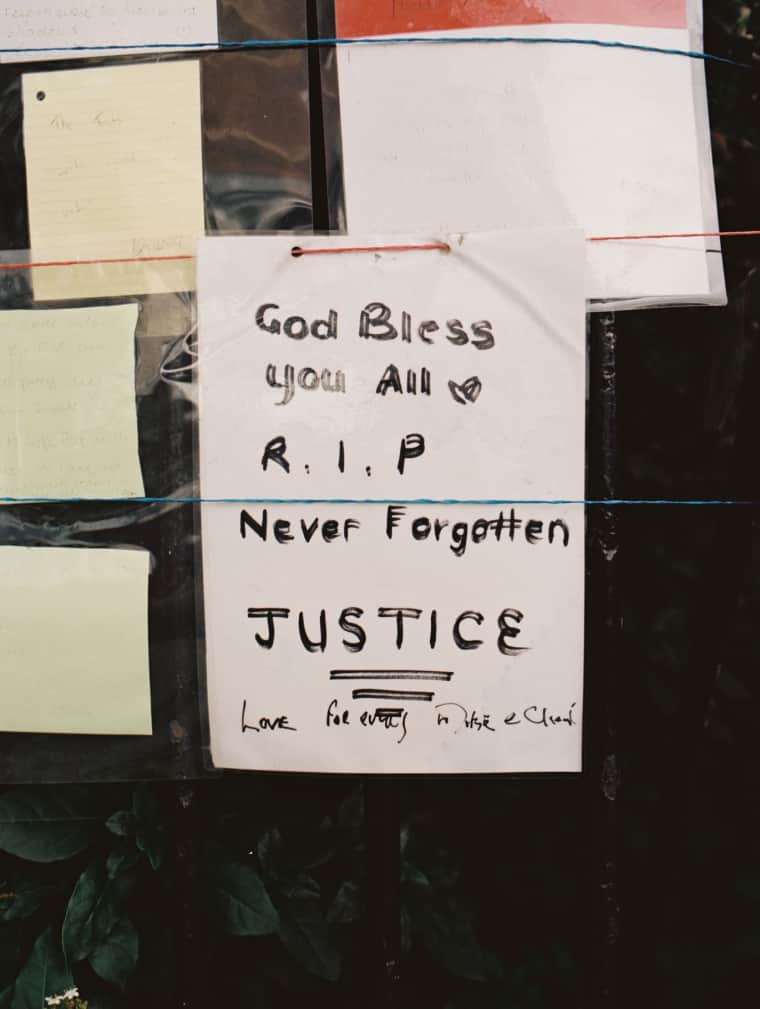

When you disembark from the tube at Latimer Road station in west London, it’s impossible not to see it. Grenfell Tower, the 24-story social housing block that caught fire in a massive blaze on June 14, killing at least 80 people, stands blackened and hollow. Walking around the quiet, leafy borough in late September, three months later, the sight of it hits you at random times — not only the inescapable tower itself, but the memorials, the “Missing” posters, the flowers, and the graffiti that clings to every stretch of wall, paying tribute to the dead, and demanding answers from the government who let them down. Grenfell Tower is no longer on the front pages of U.K. newspapers, nor being raised in parliament, but here, the mourning is still fresh.

For a group of young people who live and work here, it’s important to show the rest of the country that this tragedy continues to be painfully omnipresent. Together with director and organizer Nendie Pinto-Duschinsky, a group of people who either lived in the tower or volunteered in the relief efforts following the fire have produced a half-hour film titled On The Ground At Grenfell. The film — due to be shown in U.K. Parliament later this year — shows first-hand accounts from survivors and volunteers, interspersed with brand new footage of how powerfully Londoners came together to support one another in the wake of the disaster.

“It was by far the hardest shoot I’ve ever had to do,” said Pinto-Duschinsky recently. “So many people helped us; all the young people and survivors speaking in the film gave everything they could. They were exhausted after their interviews. But it’s striking how jaw-droppingly honest they are, and I think that’s why people have responded to their accounts. The film’s missing that production company slickness — we wanted people to see how harrowing things really are. That’s why there’s no soundtrack on the film, it’s only the sounds of the fire and the heart monitors and the streets that you hear. Hopefully that makes people feel what it’s really like to be there.”

A short walk from the tower, an art project called “24 hearts,” by a local artist named Sophie Lodge, takes the form of 500 cardboard shapes bearing messages from local people. One reads: “It used to be us versus them. Now it’s just us.”

Among the locals and volunteers from the team behind the film that I spoke to, that sentiment was repeated: the community feel that they have been left alone. Many survivors are still waiting for housing, and for aid; many locals feel shut out of the government inquiry, and abandoned by the authorities in general. Read their thoughts below on why we need to keep talking about this tragedy, and watch an excerpt of On The Ground At Grenfell here.

Reece Yeboah

Local resident, volunteer

“[On the day after the fire], everybody was just going through mental shock. It was a bit of the blind leading the blind. I was [packing] clothes, unloading cars, moving boxes, sorting out accommodation. I tried to do everything I could. I got sick [from smoke inhalation] the third day, but I kept going. It was all the people. We were our own government for that week. We had to help in that situation, because if we [waited], it would have been the same situation as the people in the fire, when they were told to wait in their [apartments]. You’d be waiting until you’re dead, basically. There’s people still waiting for housing, four months on. You just have to help, when you can help — immediately. And we did that.

“Two weeks after, [I tried] to let it all soak in, the realization of what actually happened. You come to the understanding that you’ve lost people in there. Now, it’s just quiet. The first day, about two or three thousand people were about in the streets, just roaming. [Now it’s just] one person, always reloading the flowers and pictures. It was the same with the camera crews. The first day, every camera crew in the country was here. Then they all went.

“We’ve got to keep pushing and get this film out there, get it onto a proper platform. Because [the public] don’t really understand it from this point of view; they just see it on the news, then there’s something about Trump or Brexit. They’re not really focusing on this. I read in the news that [the U.K. government] donated a lot of money to the hurricane [relief] — but we still haven’t sorted out this situation. What I want [people] to know is that there’s no help [being provided], with the inquest, with the survivors; there’s no help with getting justice or getting answers.”

‘Strength’ street art under the Westway, outside Maxilla Social Club, two streets over from Grenfell Tower

‘Strength’ street art under the Westway, outside Maxilla Social Club, two streets over from Grenfell Tower

Memorial sculpture under the Westway, outside Maxilla Social Club, two streets over from Grenfell Tower

Memorial sculpture under the Westway, outside Maxilla Social Club, two streets over from Grenfell Tower

Adrianne McKenzie

Volunteer, filmmaker

“We needed to give the survivors an avenue to talk, and to express themselves. People seem to have this view that [the survivors] are looking for handouts, or they’re looking for an upgrade on their living situation. And that’s not the case. I don’t think people realize that they are literally starting from scratch. I was like, “All of this needs to be documented, it needs to be shown. Because these are people, they’re not animals, they’re not statistics.”

“I think it’s a class thing. People look down on working class people, they think they’re aggressive, they just hang on the block, they’re uneducated, or they’re just up to illegal things all the time. [The people behind the film] did an interview with Channel 4, and as soon as that went up, there were negative comments directed at one of the guys in the film, [saying] “Why is he dressed like that? What does he do for a living?” It’s sad that people still think like that.

“Loads of people lack empathy to this [situation], and it’s really weird, because around here, in our community, we can see that people are still upset, they’re still outraged. But loads of people do not care; they don’t understand why it’s still a topic of conversation. People need to learn to love each other — not look at anybody’s class, just help and support each other.”

Swarzy Macaly

Volunteer leader, radio presenter

“[While volunteering in the days following the fire], I didn’t meet anyone from the council, or anyone of authority. We read on Twitter [that donations were] going to Westway [sports center, where survivors were]. So I ran over to Westway and said, ‘When can we get our stuff to you?’ They said, ‘No, we’re not taking donations.’ They were blunt, dismissive, very discouraging. That was my only encounter with any authoritative figure. I was so frustrated, because I thought, The channel of communication is closed, no one knows anything. That’s when I [took charge]. After that, people were a lot happier to just take orders from the community. It was three days [after the fire] before there was some sort of appearance from a council member. By that time, people were like, ‘You’re too late.’

“I was really upset that the media chose to just focus on the anger and the quote unquote ‘riot,’ and didn’t really shed light on the wonderful work the community had done. Love is very strong. It sounds so corny, [but] I’m talking about a love that quiets anger or hugs grief. I’m talking about a love that will put someone else’s needs before their own. People took days off work [to volunteer], people slept rough. That’s the kind of love that the community survived on, and continues to survive on. Because when the authorities don’t show you that love, where they drop everything to meet an emergency, you feel it. You feel abandoned. Had it not been for the community, the survivors and local residents perhaps wouldn’t have got to where they are today.”

Memorial tributes near Latimer Road tube station, near to Grenfell Tower

Memorial tributes near Latimer Road tube station, near to Grenfell Tower

Hesketh Place, a nearby social housing block, built in the 1930s

Hesketh Place, a nearby social housing block, built in the 1930s

Samiah Anderson

Local resident, now organising an independent inquiry

“This massive amount of attention came for [Khadija Saye] when she passed, and that was really sad. We went to school together. She’s always been talented. It’s bittersweet, because it’s her story, and people need to know it. But it shouldn’t have taken this for people to know her name.

“[This disaster shows] the practical ramifications of when you have austerity. This is what goes wrong, when we have privatisation and deregulation. I got really geared up after this documentary, and speaking to everyone in my department [of economics, at south London university Goldsmiths]. It was like, we can’t let people get away with this. So I [thought], How can I use my skills and my degree to help my community? I began going to the meetings with the council. Everyone in the community said, “There’s a panel that Theresa May has appointed to the official inquiry, and they do not represent us [or] understand us.” There was a massive concern about discrimination, and the official inquiry being a whitewash. And it’s not addressing the issues to do with social housing. That should be the focus, of at least some part of the discussion.

“An alternative inquiry sounded like that’s what we needed to do. So at the moment, we’re working alongside the Grenfell Community Organisation. What we’re doing at the moment is trying to decide [the remit of the alternative inquiry] with them. We have the intention to hold hearings. We’re at the proposal stage, but there’s a lot of support from the survivors to have that conversation, because they really do want justice to be served — not for themselves, but for the people that have passed. They keep saying, ‘We won’t let these people die in vain.’”

Shona Harvey

Local resident, volunteer

“The news channels have got their own agenda. So [with On The Ground At Grenfell] we wanted to make something that was more peaceful, and more real. [We wanted to] get [survivors’] perspectives across and let everyone know what’s happening here.

“There’s earthquakes and hurricanes every minute, so that’s going to be the main headline [replacing Grenfell]. That’s how it is. But it’s a shame, because it’s far from finished with Grenfell. There’s a lot that needs to be done, there’s a lot of questions that haven’t been answered. It’s going to take many, many years to rebuild the community, and get justice for what’s happened. People in this area will always feel passionate about it.”

Grenfell Tower, west London, September 2017

Grenfell Tower, west London, September 2017