These photos show just how much Puerto Rico still needs our help

“Help within your means and inside your spaces,” says photojournalist Mari B. Robles López who has been documenting the post-hurricane desolation.

A man observes from his window the city below the day after the hurricane. His building suffered some damage. San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

A man observes from his window the city below the day after the hurricane. His building suffered some damage. San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

A few days after Hurricane Irma, [Puerto Rico found out] that there was a tropical storm headed our way. Some parts of the island had recovered the electrical system but most areas were still in the dark. We had just used up most of our emergency resources on Irma and then suddenly, this tropical storm turns into a huge hurricane. All the weather models showed it landing on Puerto Rico and crossing the island from southeast to northwest, as a category 3 hurricane.

A few hours later, though, María was already a cat-3 hurricane and was expected to hit us at least with a category 4 strength, still crossing us whole. We stocked up as best we could. We bought canned goods, filled all of our bottles and gallons of water for drinking and cooking and flushing the toilets. We covered the windows, the doors, our houses. We filled our tanks and that Tuesday night we waited.

And then she was here.

A man throws out water from his business that flooded during the hurricane in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2017

A man throws out water from his business that flooded during the hurricane in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2017

A gas station destroyed by the winds in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

A gas station destroyed by the winds in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

A lot of trees were ripped from their roots by the hurricane. Most landed on streets or houses, either blocking them or causing some damage. San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

A lot of trees were ripped from their roots by the hurricane. Most landed on streets or houses, either blocking them or causing some damage. San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

María landed in San Juan around 2 a.m. on Tuesday, with tropical storm winds raging at 60mph. By 8 a.m. the next day she was covering parts of San Juan with as much as five feet of rain and winds of over 200mph. Some parts of the island felt winds of 235mph.

My windows looked like they were going to shatter. I woke my boyfriend up and took him to the safest place I could think of: the bathroom. We stayed there for five hours while the worst was over. My cat Fuji was not very happy. María left the island the following Thursday around 12 p.m. And then it was time to assess the damage.

Solar panels from a nearby school were stripped from the ceiling and landed on the street in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2017

Solar panels from a nearby school were stripped from the ceiling and landed on the street in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2017

Curious people wander the streets the day after the hurricane in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

Curious people wander the streets the day after the hurricane in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 21, 2007

Gas lines in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico. Most lines lasted around 7 hours during the first days. September 24, 2017

Gas lines in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico. Most lines lasted around 7 hours during the first days. September 24, 2017

I knew beforehand I was going to document this event. I’m not from the capital, I come from a coffee town in the southwest part of the island called Yauco. I used to live in an area that flooded when it rained, so I know what it is to lose everything. I knew this hurricane would destroy my island, I knew the people who couldn't prepare as much as I had would be hit worst. Even so, nothing could have prepared me for the things I’ve seen.

Gas lines in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico. Most lines lasted around 7 hours during the first days. September 24, 2017

Gas lines in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico. Most lines lasted around 7 hours during the first days. September 24, 2017

Gas lines in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico. Most lines lasted around 7 hours during the first days. September 24, 2017

Gas lines in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico. Most lines lasted around 7 hours during the first days. September 24, 2017

As soon as I took a step outside, I started taking pictures around where I live. Most windows were broken, most areas flooded, so many people frustrated. On my way I met some people that had lost their home. Then I met three more people whose house collapsed, and so on, only in the San Juan area. I thought to myself, this isn’t the worst of it, so during the last few weeks I’ve been traveling around the island listening to the tales of the least privileged people. Documenting all of their loss; their pain. I decided to use my work to give a voice to the people that are slowly forgotten, especially in moments like this.

The areas I have documented are in general very poor areas, [cut off from communication] due to the fall of bridges, trees blocking the road or flooding. In most areas we visited, the residents cleared the roads before the government even came to assess the damages on infrastructure. Residents swept and cleaned the water out of their homes. They fed the children and elderly while they waited for aid.

People gathering drinking water in Cayey, Puerto Rico. Some go to the oasis the government sets up, others go to rivers and springs. September 25, 2017

People gathering drinking water in Cayey, Puerto Rico. Some go to the oasis the government sets up, others go to rivers and springs. September 25, 2017

People gathering drinking water in Cayey, Puerto Rico. Some go to the oasis the government sets up, others go to rivers and springs. September 25, 2017

People gathering drinking water in Cayey, Puerto Rico. Some go to the oasis the government sets up, others go to rivers and springs. September 25, 2017

A family picks up what the hurricane left of their house in Aibonito, Puerto Rico. September 25, 2017

A family picks up what the hurricane left of their house in Aibonito, Puerto Rico. September 25, 2017

10, 15 days after the hurricane I’m still visiting places where I’m told the government and FEMA haven’t bothered to show up. [They] have no running water, no drinking water or provisions, no electricity. 95% of Puerto Rico is still in the dark due to a complete collapse of an already weathered and dated infrastructure.

The houses in these areas are made of wood planks and zinc roofs. Houses like these are not meant to withstand 200mps winds, so they lost as little as their roofs or as much as everything. We were the first people to get to some of the barrios we visited, so for some people, we were the first people “from the outside” to have worried about them and to actually go to check on them.

A woman and a child walk down a now dirt road with some provisions in Yauco, Puerto Rico.

Yaucos’s town was flooded by the Luchetti River, whose original channel crossed through homes that are right next to it, a banana farm, and a baseball park. September 26, 2017

A woman and a child walk down a now dirt road with some provisions in Yauco, Puerto Rico.

Yaucos’s town was flooded by the Luchetti River, whose original channel crossed through homes that are right next to it, a banana farm, and a baseball park. September 26, 2017

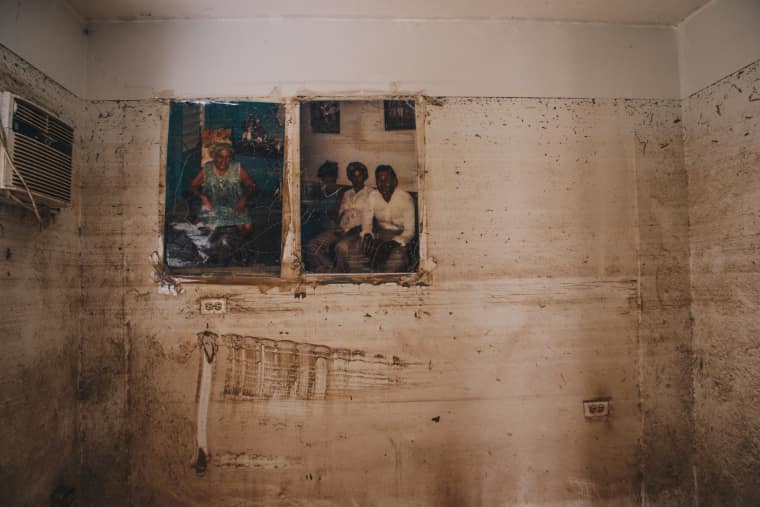

The results of the flooding in a residents home in Yauco, Puerto Rico. September 26, 2017

The results of the flooding in a residents home in Yauco, Puerto Rico. September 26, 2017

Dead crabs washed up near residencies in Yauco, Puerto Rico, because of the flood. September 26, 2017

Dead crabs washed up near residencies in Yauco, Puerto Rico, because of the flood. September 26, 2017

A family portrait floated to a neighbor's house in the flooding during Hurricane María in Yauco,

Puerto Rico. September 26, 2017

A family portrait floated to a neighbor's house in the flooding during Hurricane María in Yauco,

Puerto Rico. September 26, 2017

The amount of hungry and thirsty people we meet is overwhelming, but besides the water and food crisis, a lot of people find themselves desperate for medications. Not all hospitals are working due to lack of energy to power them, and those that are struggle to keep patients alive because of a lack of a constant diesel supply to power the generators, which in turn leads to an ever-rising death toll that isn’t being reported, and overflowing morgues.

We met families in in the rural parts of Orocovis who had someone pass away during or in the aftermath the storm, who were told to bury their fathers and brothers in their backyard because there just isn’t any fuel to power funeral homes or a way to reach them. The excuse is they live “too far out.” In one case, a whole community had to help carry the body of a grandfather into town after spending three days enclosed in a room. We met with them around 9 days after this, no one has come to help disinfect the room he was in.

A woman shows us her house in Orocovis, Puerto Rico, which was completely torn apart and

flooded. She lost her father during the storm. September 30, 2017

A woman shows us her house in Orocovis, Puerto Rico, which was completely torn apart and

flooded. She lost her father during the storm. September 30, 2017

A whole house destroyed in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico. September 30, 2017

A whole house destroyed in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico. September 30, 2017

A whole house destroyed in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico. September 30, 2017

A whole house destroyed in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico. September 30, 2017

A flooded home in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico. The mud marking on the wall lets you know where the water reached. September 30, 2017

A flooded home in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico. The mud marking on the wall lets you know where the water reached. September 30, 2017

A funeral home owner shares his frustration as he tells us how his workplace was flooded. September 30, 2017

A funeral home owner shares his frustration as he tells us how his workplace was flooded. September 30, 2017

15 days into the crisis, every single town we’ve been to is filled with people who are angry, frustrated, but mostly, tired. These communities are important and their needs have to be addressed.

My coworkers and I do what we do because we care. There is nothing else to it. We want there to be an understanding that my island is not a vacation destination — we care about people realizing [that] wonderful, humble, people live here. People who love and feel and hurt. [People] who are being forced to leave their lives behind because they have nowhere to call home and there’s more hope at the end of a $50 flight to the mainland than there is in an endless wait for government to give a care their way.

We care that their stories get out, that people recognize themselves in us. Our only message is that: Care. Help within your means and inside your spaces, and always remember “que más abajo vive gente y sin luz eléctrica.”

A family trying to communicate with the other side of the road in Ciales, Puerto Rico. Because of the strong winds and the rain, the bridge that connected this community with the main road

collapsed, leaving them without any communication with the outside world. September 30, 2017

A family trying to communicate with the other side of the road in Ciales, Puerto Rico. Because of the strong winds and the rain, the bridge that connected this community with the main road

collapsed, leaving them without any communication with the outside world. September 30, 2017

Puerto Rico still needs your help. Find out how to donate here.

Additional reporting by Jade Gomez.