Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani has an eye and an ear for mischief. The Moroccan-born, New York-based artist’s body of work surfs across video, sculpture, multimedia installation, drawing, and Instagram. Surreally layering the visual languages of documentary film, 3D animation, music videos, and soap operas, she composes worlds that obscure the boundaries between real and virtual, offering a frenetic, often hilarious lens on our media-saturated present. Depictions of a rapidly developing Morocco are augmented by the presence of figures that mysteriously balloon in size, slapstick MIDI sound effects, and CGI flies singing Rihanna’s “Kiss It Better” in a high-pitched whinge.

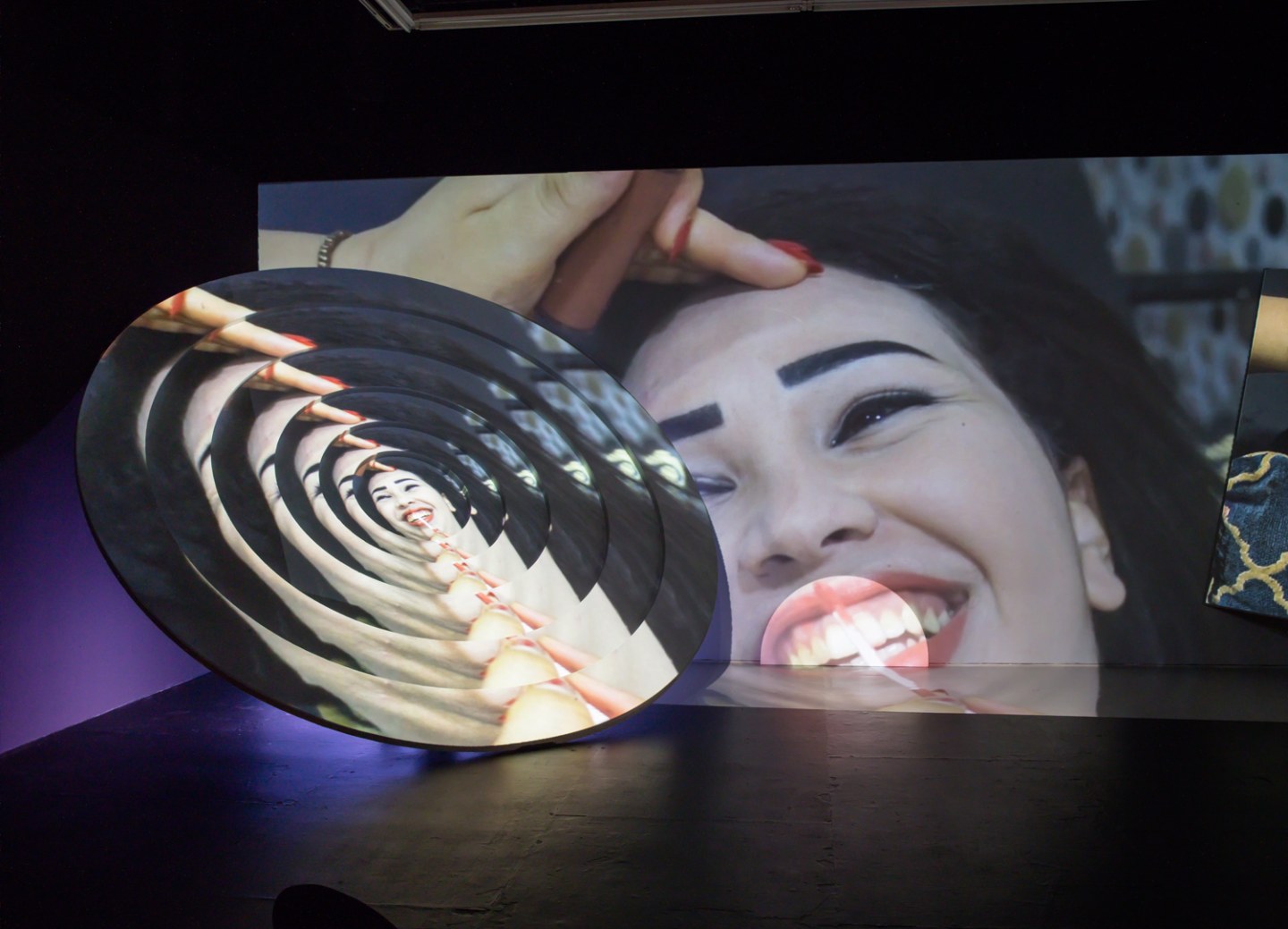

For her most recent show Siham & Hafida, currently showing at The Kitchen in New York, Bennani turns her attention to the contemporary status of chikhas, women performers of the historical Moroccan genre of aita music. Developed as a sly tool for spreading poetic messages of resistance during the period of French colonial rule, aita and chikha performers face a contemporary crisis of character.

The exhibit documents two currently practicing chikhas, pairing Hafida, an older, headstrong veteran of the style, and Siham, her younger, chirpy, social media-savvy counterpart. It’s a classic inter-generational feud, complete with slights of the others’ talent and respect for the genre’s traditional roots and a final showdown reminiscent of reality TV’s sharpest editing. In the end, the work doesn’t provide any resolution between the two but offers up plenty of petty drama and a nuanced reflection on how women’s roles have been traditionally embodied and performed within Moroccan culture over time.

Projected over six irregularly shaped surfaces, Siham & Hafida is a rollicking and seductive account of gendered history and how the past is embodied for us in the present. Computer generated crabs and butterflies scurry and float through scenes, digital interruptions introducing a subtle absurdity and humor into the whole affair. Simultaneously projected channels compete for the viewer’s attention, mimicking how we seamlessly transition between screens in everyday life, constructing new narratives in the process.

The FADER spoke with Bennani about Siham & Hafida, her interest in different forms of language, the floating power of Facebook, and the clap emoji.

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Growing up, in what ways were you aware of or exposed to aita music and chikha singers? Was this culture prevalent to you while you were younger, living in Morocco?

The chikha character is something that everyone knows, it’s a big part of popular culture. So I was always aware of it, but like a lot of people I was mistaken and I thought it only had to do with dance. I was aware of how eroticized the chikha figure is, being attached to the idea of a ‘bad girl’ or a bad reputation.

I don’t think I realized what aita music really was [growing up]. I knew about chaabi music and I thought that was what chikha performers danced to. I just had this very blurry idea where I was kind of confusing everything. Later on, when I became more interested in different types of Moroccan music and doing research and listening to stuff, I realized that aita was a very specific genre that I had already heard some songs of.

I realized that chikha figures were a very different thing than exclusively dancers. These women sing a repertoire and have gone through a very specific training allowing them to master the techniques and rules around the songs.

Why this work now? What led you to this subject matter?

Well, for me, the subject matter [of Siham & Hafida] is not the chikha singer or the aita music, really. They’re more the structures that allow me to approach other subject matter. For me the main subject matter has to do with performativity and the generational gap and reflecting on time and womanhood through time. Also language and the complex cultural reality and moral code that are very symptomatic of its colonized past, for example.

The reason I ended up talking to these women and using their stories to talk about these other issues is because my past projects have mostly featured women in my family. I wanted to film women but be in a situation where I wasn’t with people I know or grew up with.

I got really into this chikha performer named Chikha Tsunami. She became really famous in Morocco, she’s like the person you want at your wedding. There are a lot of videos of her dancing up on YouTube so I could just follow her work from New York. I thought she was a chikha and she also identifies as one, which is a hard thing to identify as proudly for Moroccan women. So I was like, This is really cool, she really places herself in this tradition and not a lot of women say they’re chikhas. But I wasn’t actually fully understanding things. I met up with her [when I was in Morocco] and asked if I could film her when I got back. I came back to film and, as I expected, she completely flaked.

But because I [guessed] that would happen I had a plan B. I did more research about chikha women and aita music and would always come across the name of this guy, Hassan Najmi, who writes about the genre. So I found him on Facebook and asked him to help me and put me in touch with some women. He sent me to Safi, which is the capital of aita, where I went and spent two days [with Siham] and two days [with Hafida].

It was funny because through [Najmi] and through these women, who are really veterans of the style, I realized that [Tsunami] hadn’t been trained. Not that I care — there are strict rules within the genre and I’m just reporting — but they all had big problems with her. For most people the chikha represents this eroticized nightlife dancer figure. They’re fighting to change this image and to be like, “No, we actually just sing.” But [Tsunami] gets popular because she’s very charismatic, she lives in the biggest city, Casablanca, and goes to all the VIP stuff. So she’s seen as ruining all of this work and they don’t consider her to be a real chikha.

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

“There’s something about language being the only weapon that is very desperate but also very beautiful.”

The exhibition literature discusses how aita historically emerged as a kind of anti-colonial code or language for performers during French colonial rule in Morocco. Does aita music still carry the same kind of political messaging today?

The thing that’s strange about aita is that the repertoire is composed of songs that were written a long time ago and haven’t evolved. So there’s a certain number of songs and those are the only songs you can learn. You have to learn how to master them and then once you get really good, you personalize them. The way that you can unlearn stuff [is] once you really know the technique. I didn’t fully do research on it because the goal here wasn’t to make a documentary about the genre. But from what I learned, the first thing is that anything that has to do with aita’s history is blurry because it’s from an oral tradition. So there isn’t much writing about it. It has circulated orally.

This is what makes aita so strange, because it’s so slippery and it’s in this language that the French colonizers couldn’t understand. And it’s also in a very poetic language where everything is analogous. It uses the trick of writing analogies in order to be politically critical so that you can’t be censored. The colonial aspect was completely a big part of it, and it’s really powerful. There are many aspects [to aita] of course, but I chose to highlight this one because I liked it. There’s something about language being the only weapon that is very desperate but also very beautiful.

The body plays such a large role in aita and in your video. There’s this idea here of the body as this archival vessel for knowledge and creativity that performs but also erodes. So, over time, traditions carry and are shared intergenerationally but also break and transform into new languages in the process.

Totally. That’s the idea that I came across while doing research that I’m most excited about and is a big part of this show. You know, these women have such a hard time. Chikha has become a term used to kind of mean “slut” sometimes. So that’s a reality. But the other reality is that all the people I met in Safi said that aita is way better for female vocals, although some men do sing it. Everyone seems to agree on that. So the chikha, through her body, does circulate an archive of Moroccan history and Moroccan language and how it’s evolved. That’s a really powerful idea.

The other aspect of this, which has come with the internet, is that now YouTube is also an archive. Some people have transcribed the songs. The man who put me in touch with these women has transcribed them into Arabic, but besides this there’s no access to them. So the digitalization of these performances has become this thing that works in parallel with these women as vessels.

There’s a big sequence [in the work] where there’s a woman dancing and I applied this effect where she kind of turns into this mess of pixels. It was the most obvious scene where I could turn her body into digital matter. I mean, that sounds cheesy and very straightforward. It was like data going through YouTube or the idea of streaming.

Looking at you greater body of work, you’ve created this very recognizable visual language, whether that’s through the use of after effects or animation. How do you see this process of developing a visual language relating to the subject matter, which deals so much with how language changes over time?

Well, I guess there are multiple languages in my work. That’s the language, right? Like, there are moments of reality TV inspiration, there are moments of straight-up documentary inspiration, there’s animation which is mostly hentai references in this one.

First there’s this language that’s just my way of expressing things that is consistent through my work. But then of course this adapts to the subject matter. Here I feel like the documentary references made sense in that this was my character when I was there with [Siham and Hafida]. They thought I was coming to do a documentary about chikhas and aita. But I was really transparent and I told them, “That’s not what I’m doing, I’m just documenting two women from generations and it’s gonna be an art piece and through the editing I’ll figure out the story.” But I guess, you know, [the documentary aspect] reflects on that experience of meeting them.

The animation and the music montages had a little bit of a hentai reference, but also they’re 3D, which is a very common thing to see today. I was wondering what the cartoon language would be for this piece. Because it couldn’t be American cartoons – that just wouldn’t make sense. And it couldn’t be anime because that also wouldn’t make sense. So my thought was that if there was a Moroccan cartoon created today, it wouldn’t have a very specific look. It’s too late. [Cartoons] are too globalized and there would be too many references.

So there was this idea of creating something that carries many aesthetic references, but functions as the complete opposite of aita. Aita is completely paralyzed in history, it can’t evolve. New instruments or electronic instruments can’t make it into productions because it’s so about who has the most ‘pure’ practice of the art. So in a way, that’s what’s participating in making it die out or why young people don’t care about it as much. I wanted to develop a cartoon that was its opposite — only taking on things that are new.

The music is all Japanese new wave from the ’80s and raï music. Raï music is pop music from Algeria and Morocco that people love and that has evolved and talked about new things over time. I wanted to make these choices that completely balanced things out. I didn’t want it to be completely about aita and wanted to make it a universal work. You can watch it and see that it’s about two very specific women in a very specific city and a very specific music genre that’s extremely niche, but at the end you have all these tools for reading it that are extremely universal. It doesn’t really matter where it comes from. The tension, the drama, and the storytelling are what remain.

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

Meriem Bennani, installation view of Siham & Hafida, 2017

Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Kitchen

“The chikha, through her body, does circulate an archive of Moroccan history and Moroccan language and how it’s evolved.”

In addition to drama and stories, humor obviously plays a huge role for narrativity in your work. It’s this very zany, off-the cuff-style. Humor in a way gives us this closer window into emotion and intimacy.

I think humor does both in the case of my work. Humor and my own reaction to things act as my presence in the work. It provides a way for me to connect with the characters and also whoever is watching. So it is intimate, but also it has this effect of pushing things away. It takes over any potential for other emotion.

I want to know a bit more about the projection surfaces that were installed in the gallery. In the main space the projection surfaces are multiple, creating this fluidity and instability between the different video channels.

This was mostly part of this larger research into wondering why we always show things in a single channel. Like, is that still accurate in terms of our relationship to the screen today? We are constantly connected to multiple screens and we can navigate that so seamlessly. So isn’t it more true to our experience today to show things on different screens?

Why specifically use the crab and the butterfly in this work?

This is the question I would ask, too. But honestly, I think that the answer is so straightforward and not that smart: the older one is the crab and the younger one is the butterfly. For me it was a way of creating extensions of the characters that I could reanimate as animals or cartoons. And it’s also this classic idea of using cartoon symbolism. They have different functions at every moment, depending on which screen they exist within.

Have Siham and Hafida seen the work? Or have they had any interest in seeing it?

So for Hafida, if I go to Morocco and I go to Safi, I’ll try to show it to her because I don’t have a way of reaching her. And I haven’t really shown it to Siham because I don’t know if she’ll be happy. But I think I should do it. Hafida doesn’t seem to care that much and also I don’t have any way of reaching her besides by telephone.

I sent Siham a couple clips because she really wanted to see some of when she’s rehearsing, just for her YouTube page. I sent her a few things because I was starting to feel guilty the more I was animating. She doesn’t really know my work and doesn’t exactly know that every time I shoot something else would happen that she wouldn’t be aware of at the time. So in an effort to be more transparent I sent her a few clips where I had animated butterflies on her face. I was like, “Do you like the butterflies?” And she was like, “Yeah, they’re beautiful!” But she really didn’t care. I sent it to her and she sent me the clap emoji.