If you're a raver, you see your city's streets in every kind of light. The brooding shadows of the midnight shift. The soft focus of pre-dawn. And the rude, hi-def splendor that greets eyes emerging from an all-nighter. In the intimate hours between days, certain streets outside underground clubs, bars, and warehouses are transformed. Soaked in the warmth of shared confidences and cigarettes, a scuffed up bit of pavement can become a nook — somewhere to huddle with friends and speak dreams into the breeze, before breathing deep and diving back into the dance. In the afternoon sun of the following day, the same spot will look ordinary, but you’ll know different.

On the Sunday night of a hot mid-May weekend, the street corner outside Bushwick’s Bossa Nova Civic Club plays host to such a scene. People borrow lighters and trade names, drawn to one another like moths to a flame. While most of the city sleeps, one hundred or so bright young things have come together to party into the early hours of Monday. It’s a birthday party for Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson — the visionary 30-year-old co-founder of Discwoman, a collective and DJ booking agency that exclusively represents cis women, trans women, and genderqueer artists — and her friend Gregory, who is a loyal regular of the supportive scene Hutchinson has helped build.

Inside, Frankie’s Discwoman partners are behind the decks: Emma Burgess-Olson, 28, who makes spare yet dynamic techno as UMFANG, and Christine McCharen-Tran, 29, an event producer who is the business brain behind the operation. Dressed respectively in a voluminous white jumpsuit and a baggy black shorts and tee combo, the pair make a point of playing Rihanna’s “Sex With Me” for Frankie, who hot-foots it to the front in a cheetah-print crop top and patterned pants. Discwoman is often associated with techno, but tonight anything goes: reggaeton, Afropop, rap. The lights rotate through vivid blues, greens, and pinks, while the fog machine exhales deep, creating an ever-shifting space in which guards lower and spirits rocket sky-high. The crowd is mostly N.Y.C. club kids, including GHE20G0TH1K artist LSDXOXO, Tygapaw of the queer collective Fake Accent, and local rapper Quay Dash, whose last record was packed with anti-transphobia anthems. Later, ascendant stars Kelela and Moses Sumney roll up to let off steam after a gig. But nobody’s dancing harder than Yulan Grant, a.k.a. SHYBOI, one of the eight artists signed to Discwoman’s agency. In a corner with her baby sister, she twists and leaps, channeling the music with her body.

“Being a part of Discwoman has been a game changer,” SHYBOI tells me later. “They’ve been so great at constantly outlining and reifying their ethos that it’s inspired me to be even more upfront with what I want from a nightlife space and those who organize those spaces.”

Club culture is nowhere near immune to the systems that enforce the status quo. “It’s without a doubt that queer women/gender-nonconforming/trans artists, especially those of color, are treated differently than their white male counterparts [in the music industry],” SHYBOI continues. “Having the backing of these incredibly talented people has pushed me to test myself more, tweak a boundary here and there in a different direction. No one on this roster takes any bullshit.”

As SHYBOI hints at, creating a space that is truly supportive is not a one-off job, it’s an ongoing process. One that requires patient negotiation and tireless listening skills. For Frankie, Emma, and Christine, launching Discwoman has been more work than they’d ever imagined — and a test of their friendship.

Reveler at Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson's birthday party at Bossa Nova

Reveler at Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson's birthday party at Bossa Nova

Until she turned 8, Frankie lived with her parents and older brother on a council estate in London’s Hackney borough. Her father was an alcoholic, and was physically abusive to her mother. “One day, my mum came and took me and my brother out of school and said, ‘We’re leaving your dad right in this moment — your dad knows and he’s coming for us.’” Her mum hid them in a doorway around the corner from the school as they watched their father pass by on foot. “That was one of the last times she’d see him for a really long time,” Frankie says. “Same for us, actually.”

We are perched on a sofa in the cozy Bed-Stuy apartment she moved into just a week ago. It’s the first time she’s had a proper base in months of sleeping on friends’ couches, and she’s relishing the sense of security. While we talk, her new roommate, Stephen, quietly dishes out wine and weed before retreating to his room to give us space.

Frankie’s mum found a place in a women’s refuge in north-west London, where the three of them ended up staying for two years. “We shared one room, literally pissing in a bucket. It was really intense.” Between the stress of their living situation and lack of money, Frankie’s mum was miserable — but she took pains to empower her young daughter. “From as young as I can remember, she would just be like, ‘Kick men in the nuts,’” Frankie says, laughing. “She tried to drill some sense of self-worth into me, which now feels even more powerful than ever.”

In 2005, Frankie moved to Sussex for a degree in Film Studies and American Studies. (Her mother had remarried an American and moved to New York, which granted Frankie a green card as a minor; the city was in her sights.) “As soon as I got there I knew I didn’t fit in,” she says of university. “Finding out that a bunch of people’s parents paid their rent for them, I was like, What is going on here? Alarm bells were going off.”

There wasn’t just a massive wealth disparity on campus; racism was also rife. “I was living in a house with eight or ten people, and I got really close with this girl,” remembers Frankie, declining to name her. “Meanwhile, I had developed friendships with some black friends — Kuchenga, Patrick, and Xavier — and they were becoming really significant relationships to me.” When it came to sorting out a place to live for the following year, Frankie suggested to her housemate that they all live together. “She said, ‘Frankie, can I talk to you?’ She was squirming a little bit. She said, ‘I just really don’t feel comfortable living with all black people.’ It was a fucking kick to the stomach.”

“I said, ‘I’m the only black person in this house, what do you think my experience is?’ I got up and ran to my room. This white girl who lived upstairs came down and I heard her say, ‘Did you do it?’”

It was Kuchenga who saved Frankie in that desperate moment, and who she went on to live with. “She validated what I went through, she understood it,” says Frankie, explaining that Kuchenga, a darker-skinned black trans woman, has experienced discrimination “on another level.” “I’ve been friends with her ever since.” It was a different story with her white friends, however. “The amount of white people who would not engage with what happened — and I told so many people about it — was insane. It was just so painful.”

Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson

Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson

“You can talk all you want, but if you’re not actually putting people on, it doesn’t mean anything.” —Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson

Looking for a distraction, she threw herself into partying. She took her first ecstasy pill at a rave called Raindance in London (she found it “so therapeutic”) and attended all-nighters in a field behind her campus where she danced to house, techno, and, notably, “Windowlicker” by Aphex Twin.

As part of her degree, Frankie spent the 2007-08 school year abroad, at the University of California in Santa Cruz. On a social level, the local nightlife didn’t hold a candle to back home, but, intellectually, studying in America opened another door.

“I discovered all these amazing writers who talked in ways I didn’t even think was possible: James Baldwin, Angela Davis, bell hooks, the usual ones,” she says. “I had a breakthrough in my understanding of myself — from being a young black girl wearing towels on my head ‘cause I wanted straight hair, to understanding that you have just been trying to obtain whiteness your entire adolescence. That was such an emotional point for me. I hated myself a lot and thought I was so ugly and horrible. You realize why — because you’ve been bombarded with all this bullshit. It’s such abuse.”

Frankie moved to New York two weeks after graduating. She worked a string of part-time jobs in her first couple of years in the city — from doing community outreach for the African Diaspora Film Festival to serving hot dogs at Brooklyn’s Trophy Bar, which is where she met the people who would go on to launch Bossa Nova Civic Club. It was, in fact, at Bossa in late 2013 that she first met Emma, who had a monthly residency there. Frankie gave her props for mixing in a “fucking dope” Call Super song, and by the following May, they were hanging out every week.

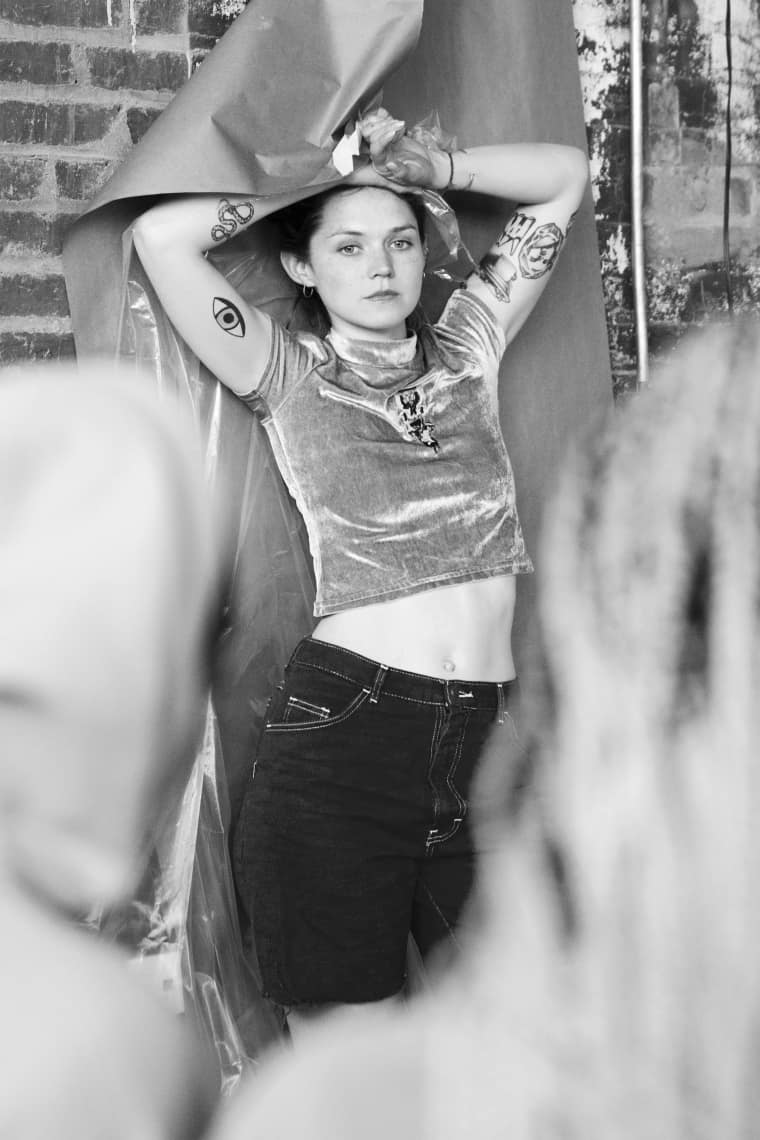

Revelers at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

Revelers at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

An only child, Emma was born in the Bronx. Her mother worked at the New York Botanical Garden, and her father was a painter. They told Emma they were breaking up when she was 3, but initially remained living together. A few years and a drawn-out divorce later, Emma found herself living in Lawrence, Kansas, with her mom. Her dad got a house just 10 minutes away. She had a good relationship with both her parents, and processed their divorce in her own private way.

“I was kind of a quiet, strange kid,” she says, over a lunch of watermelon salad in her white-walled, plant-dotted Bed-Stuy apartment. She’s lived here with her friend Bailey, who makes house and techno as Beta Librae, for the past three-and-a-half years. “I was pretty introverted, I was content to just play by myself in my room and stuff.”

Pastimes that required a lot of patience kept her occupied: hand stitching, drawing, and making jewelry. Later, she studied textile design at college in Kansas, opting to make patterns using antiquated methods like paper folding and carbon transfers instead of Photoshop. “I really have had a hard time accepting computers into my life,” she says in her unhurried Midwestern accent. “I always preferred to do things by hand.”

That perspective continues to inform her creative process today: Emma uses hardware — synths and drum machines — to write her music as UMFANG, instead of the software favored by a lot of her peers. Her path toward musicianship as a kid was stop-start. She played cello for a few years, and was also in the school choir. But it wasn’t until college that music got her full attention. She and Bailey would go to warehouse parties organized by their friend Philip in an industrial patch of Kansas City called West Bottoms. One day, having recognized their passion for techno, he told them, “I’m tired of booking straight white men so I’m going to teach you how to DJ.” Using VirtualDJ on their laptops, they would play his events, and he would game MySpace algorithms to get tons of people invited. “All these freaky young kids from Kansas City would come out,” says Emma with a smile.

Emma Burgess-Olson

Emma Burgess-Olson

“How has techno been so overtaken without any question? It made me so angry.” —Emma Burgess-Olson

At the time, she thought techno was German. “If you went to Resident Advisor as your first introduction to electronic music, which I think a lot of people still [do], you would think that it’s a white, European-invented thing that’s not really connected to anything else.” She didn’t discover techno’s black Detroit roots until she got into record digging after moving to New York in 2010. “It made me angry,” she said. “How has [techno] been so overtaken without any question? To realize that actually it’s American, and that the roots are humble, was really powerful. Being an American that didn’t grow up with a lot of money, I connected to that.”

2012 was a big year for Emma: she bought her first synthesizer, started her night at Bossa with Bailey — which went on to be called Technofeminism — and became immersed in the hardware scene that orbited the now-defunct DIY space Body Actualized. A job as an assistant manager of popular vintage shop Beacon’s Closet funded her burgeoning music career. Namechecking fellow artists Antenes and Via App, she says, “the more women I saw being experimental and going for it with synthesizers, the more excited I got.”

She still needed a push, however, to realize her own potential. “[My friend Anette] was the one who told me I had chosen to believe that I wasn’t as capable as men,” Emma explains. “I was like, ‘No, no, men’s brains are different than women’s and I’m not as good at understanding computers and computer programming.’ She was like, ‘That is not true.’ It’s funny that you can have feminist parents and still have these ideas and think that they are true.” It was this moment of deprogramming that set Emma on her current path.

Revelers at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

Revelers at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

The seed for Discwoman was planted during a conversation between Frankie and Emma in the summer of 2014. Frankie was working as an editor for an online magazine called Galore at the time, and asked Emma to write an article.

“It was about the history of techno and I had to pick some tracks,” says Emma of the piece. “I had this line, ‘Techno is black,’ and I was like, ‘Is that too political for this article?’ and Frankie was like, ‘Nooooo.’”

Emma’s recommendations led to an epiphany for Frankie: “I started doing my own research: Oh, they’re black, they’re black, they’re black. Why is Emma the one telling me about this right now?” she exclaims. “It made me think really critically about who was playing the music. I was like, Wow, I want to find black women who play techno.”

Over post-work drinks, the pair came up with the idea for a two-day event at Bossa Nova that would feature an all-woman lineup. They had some contacts between them, but pulling off an event of this size needed a professional touch. Frankie immediately thought of Christine McCharen-Tran, who she’d recently collaborated with on a Galore-backed launch party for Chromat. (The lingerie and swimwear brand was founded by Becca McCharen-Tran, Christine’s long-term partner; the two wed in 2016.)

“A lot of the people our age — and no judgement, I’m including myself — were getting wasted a lot, and Christine seemed like a real concrete pillar that was actually focused,” Frankie remembers of the Brooklyn scene a few years back. “I was really attracted to being around that kind of vibe and person.”

Christine had been throwing a monthly queer party called Witches of Bushwick since 2012, that sought to showcase the “other.” “[Lesbian spaces were] the spaces that I knew,” she says, “but they were very white, so that was something I wanted to break out of.” She didn’t hesitate to come on board.

The weekender debuted in September 2014 with more success than the three women had expected. 12 DJs, including Light Asylum’s Shannon Funchess and CREEP’s Lauren Flax, all played for free, and the money raised was donated to the Sadie Nash Leadership Project, an education program for underprivileged women in N.Y.C. and New Jersey. It was clear they’d hit on something by calling the event Discwoman.

“We came up with a bunch of names,” recalls Frankie. “Emma had ‘Disc Womyn’ spelled with a “y” but it was separate words.”

“You thought the ‘y’ was trag,” remembers Emma, laughing.

“‘Trag’ is a key word in the Discwoman vocabulary,” notes Christine. (Pronounced traj, it’s U.K. shorthand for “tragic.”)

“Once we had that name it was just like, boom,” adds Frankie.

If you didn’t get it from the women-only lineup, then the name spelled it out for you. Discwoman is a critical reading of the electronic music world, which, at both mainstream and underground levels, is overwhelmingly controlled by men — most of whom are straight, white, and cisgendered.

“We weren’t the first people to say these things about electronic music being really male-dominated, obviously,” says Frankie. “But I think why people gravitated so much to what we were doing is really because of our logo and branding — it was nostalgic and accessible.”

“All we did was collect everyone we knew and put them in a room together, and everyone was like, ‘That was amazing!’” picks up Emma. “People got really excited, emailing us, ‘I want to do this in our city.’”

In early 2015, thanks to a combination of word of mouth and media coverage, bolstered by growing online conversations about the persistence of gender and racial inequality in dance music, a series of Discwoman events mushroomed across North America, including Puerto Rico and Mexico. For each, they worked with local artists and organizers to find talent to showcase. And thanks to Christine, they began to conceive of Discwoman as a business.

Through one of Christine’s contacts, they got a weekly DJ residency. “We had a long-term plan of trying to formalize [Discwoman] through this one source of $200 a week,” she laughs. “‘If we save up for nine weeks, we can do this thing.’ It was very slow.”

Reveler at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

Reveler at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

For Christine, changing the face of who is playing and making dance music goes hand-in-hand with changing who is pulling the strings behind the scenes. “I think people just need to get used to non-stereotypical decision-makers,” she says a couple of days after Frankie’s party. “I break out of that shit. Yes, I’m as important as that white dude.”

We’re sitting at the kitchen table in the airy Bushwick apartment she shares with her wife. Next to us is a wall of framed photographs tracing the journey of their relationship: the building where Becca proposed, a special road trip, other personal mementos.

Christine’s self-determination was encouraged from a very young age. She was born and raised in Virginia to Vietnamese parents who separately emigrated to America after the Vietnam War ended. At the age of 5, her dad told her, “You’re going to be the first Asian to win Wimbledon.” Tennis is expensive, so he would volunteer as a helper at courts that would allow Christine to play for free — a lesson in being resourceful that she remains grateful for today. He also worked hard to raise funds for anything else she might need to go pro, picking up odd jobs like selling phone cards in laundromats.

Christine was her dad’s first tennis student, but he later became a certified coach and founded the Vietnamese Junior Tennis Association, an organization that provided a challenge to the whiteness of the tennis space, and also raised funds for Asian American youth charities including AALEAD. “He would let some kids play for free and [make others] pay a lot because they could,” Christine remembers. “[Creating] access to a really privileged activity is something he instilled.”

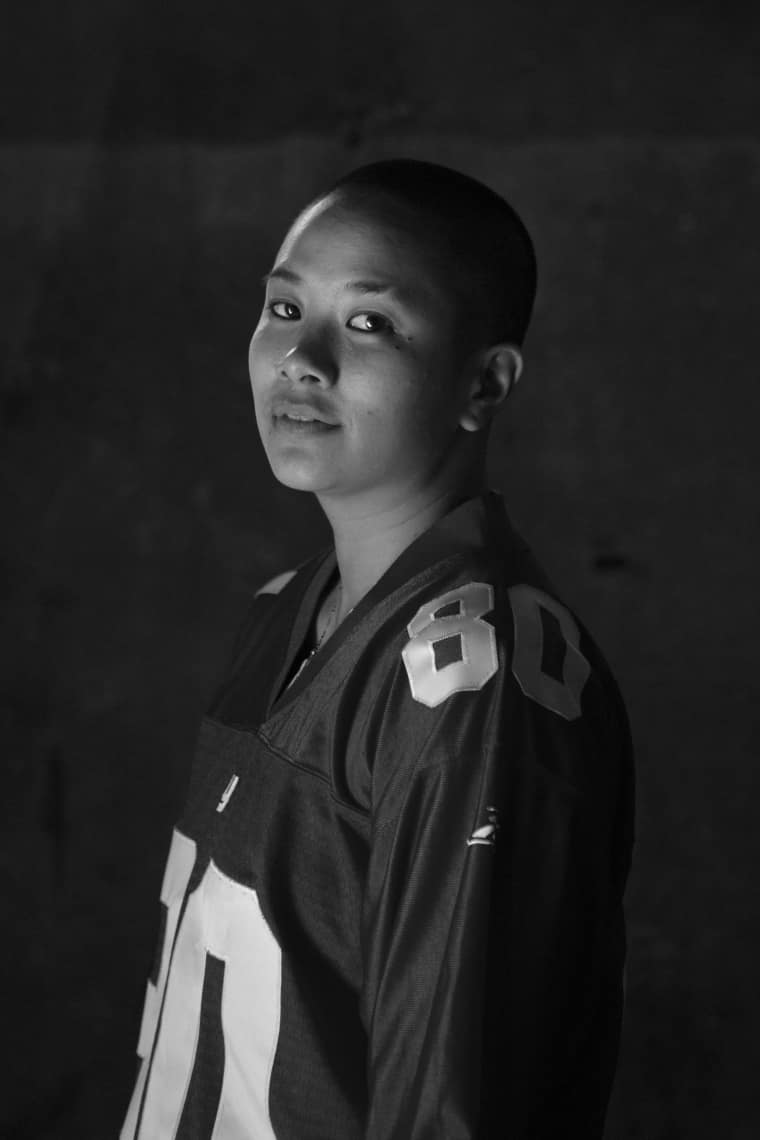

Christine McCharen-Tran

Christine McCharen-Tran

“We’re all just learning in the world. We all deserve space.” —Christine McCharen-Tran

While a career in tennis lost its appeal in her teens, Christine promised to keep it up to try for a college athletic scholarship. She won a place at Rutgers in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where she initially chose to study business, though the track turned out to be dry. “I don’t want to be a cookie-cutter business person,” she states emphatically. Within a year she’d switched to poetry, journalism, and media studies. “I lived in an art dorm, and it was funny because I’d be the jock. People would be like, ‘Why do you come into this dorm?’” she remembers, laughing. “There’s always been a theme of ‘I’m not typically supposed to be here.’ But I’m here.”

The DIY energy of New Brunswick, where punk shows were held in mattress-covered basements, pushed Christine to get creative herself. She started a zine with a friend, and made music videos around campus with visiting artists. Shooting in cars, at bus stops, wherever, they notched up close to 100 videos.

Like Frankie, Christine moved to New York within a few months of graduating. Applying for jobs on Craigslist, she got lucky and landed one working in events for John McEnroe, the veteran tennis player. The job taught her the basics of corporate-level event production, from venue agreements to client relations. Over the following three or four years, she rounded out her skill-set with a string of different jobs. The worst of them found her working for a misogynist boss who mistreated his wife in front of employees.

“I remember thinking if I work even half as hard as he does, by the time I get to his age I’m going to be so much further,” she says, shaking her head. “The anger I had towards him really energized me to start my shit.”

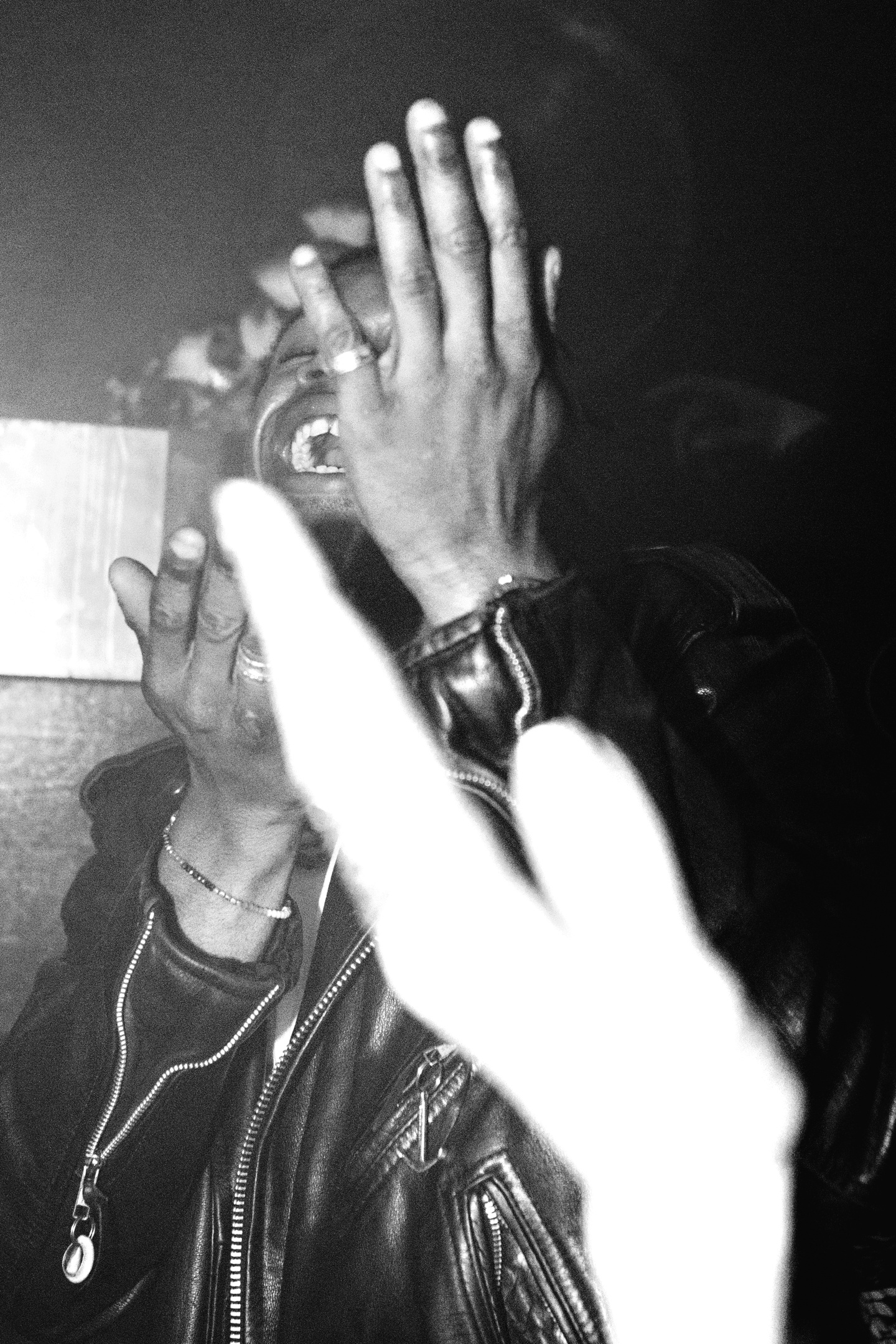

Reveler at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

Reveler at Frankie's birthday party at Bossa Nova

After the second or third Discwoman event in early 2015, the idea for the DJ agency began to take shape. Initially, it was just a joke. Emma’s DJ bookings had picked up off the back of the press around the first weekender, and the three of them would laugh about Frankie being Emma’s agent. But then it started to make a lot of sense. Putting on nights was a starting point, but truly making space for marginalized people means putting your money where your mouth is.

“The proof is in the practice,” says Frankie. “You can talk all you want about representing X, Y, and Z, but if you’re not actually putting people on, it doesn’t mean anything.”

They announced the agency in spring 2015 with two artists: UMFANG and Volvox, an established N.Y.C. DJ who plays tough-edged techno. A few months later, Frankie signed BEARCAT, a Brooklyn-via-London producer who makes potent, therapeutic soundscapes. Over email, BEARCAT sings Discwoman’s praises for “all the visibility they create for people in the intersections like myself and beyond.”

The work of running the agency is split between Frankie, who handles the day-to-day business and is in constant contact with her roster, and Christine, who looks after artist contracts, merch sales, and anything else Frankie needs support with. Emma’s involved in big decisions with the company, but as a busy working musician, her responsibility largely lies in repping Discwoman and its ethos on tour and in DJ workshops.

All three women take the development of Discwoman very seriously, but it’s Frankie who is in the driver’s seat. “All my eggs are in this basket,” she says. In the first few months, she knuckled down into research, spending days going through archived listings for N.Y.C.’s most established clubs and promoters to compile stats about the percentage of women DJs at each of their events. Shocked at the results, she called out a couple of well-known Brooklyn house and techno promoters on Twitter for the lack of diversity on their lineups. Out of shame, one of the promoters later admitted to a friend of hers that they’d never booked a woman in 10 years of doing parties.

Battling gender inequality is not the only challenge the collective has faced. Just as popular discourse has woken up to the deep-set problems of white feminism (which has a long history of racism and transphobia), the three founders of Discwoman have had to examine their own language and communication skills. Media coverage of their efforts has often pegged them as intersectional based on their identities and those of their roster. Adopting an intersectional approach, however, requires a commitment to constant adaptation.

“In the beginning, my scope and language around gender was definitely more limited that it is now,” admits Frankie. “I think that was reflected in the language we used: ‘female-identified.’ Now that does not feel sufficient. Part of what we do is try and adapt however we need to. If you’re not investing in that, then I don’t see what the point is.”

The work of intersectionality is also the work of unlearning. The systems of oppression compress themselves into human minds, bodies, and spirits, generation after generation. It takes intentional effort to unpick that influence.

Earlier this year, Emma and Frankie went through a rough patch after realizing white supremacy was at work within Discwoman, too. White artists were getting higher offers and more approval, which they found “devastating.” Emma herself has seen her star rise over the past couple of years, while, as a growing business, Discwoman was not yet providing Frankie with a regular salary. The clash, says Frankie, was “triggered by white privilege in general.”

“I was desperate to find a solution and Frankie just wanted me to calm down and listen,” says Emma. “After a while, and all these conversations, I texted Frankie, ‘I realized what I should have said is, How can I amplify you better?’”

Frankie at her birthday party at Bossa Nova

Frankie at her birthday party at Bossa Nova

These days, Frankie, Emma, and Christine are closer — and busier — than ever. The agency’s sound has broadened beyond techno with the signings of artists who join the dots between a multitude of diasporic dance music styles: DJ Haram, SHYBOI, stud1nt, mobilegirl, and Juana. “It’s really beautiful to see everyone grow in their own way,” says Christine. “Sometimes in the morning we scroll through the artist page, ‘Look at our roster, look at them.’” As a collective, they continue to support charities like Callen-Lorde, who this year honored them for “positively [impacting] women’s wellness and visibility in New York and beyond.” And thanks to money from merch (Bon Iver wore one of their shirts on stage at Coachella this year, a cosign Frankie credits for a recent sales boost), they’re in a more sustainable financial position.

This spring, Frankie was finally able to draw a modest salary from Discwoman. More recently, she also picked up a part-time role at Boiler Room, as an N.Y.C. curator and host, and founded Dance Liberation Network with a group of club owners and promoters to campaign to overturn N.Y.C.’s racist “no dancing” Cabaret Law. (It has historically been selectively enforced to close black-owned bars and clubs that don’t have a cabaret license.)

Emma’s in the middle of promoting her deeply meditative new album, Symbolic Use Of Light, on Ninja Tune offshoot Technicolour, and has been touring intensively. While Christine now juggles Discwoman with managing a performance art collective, FlucT, and a job as an experiential event producer at entrepreneur Steve Stoute’s company Translation. (Her boss, Katie Longmyer, was the one who got Discwoman their first DJ residency, and understands Christine’s commitment to the group.)

They all know there’s always going to be more to learn. “It definitely helps to have the three of us — it’s like a seesaw,” says Christine. “If there’s an imbalance, we pick each other up. Work-wise or emotionally. We challenge each other, we’re really honest with each other, and I think that’s what’s helped us grow so much. We’re all just learning in the world. We all deserve space.”

They also make each other laugh. At a photo shoot for this feature — which took place at Knockdown Center, an old glass factory turned arts venue in Queens — they all turn up wearing red, by accident, because of course. Later, Frankie poses with her finger on a light switch, joking with a wink in her voice: “What could this be a metaphor for?” It’s something of a treat to all be hanging out together — their busy schedules mean they do most of their work over group chat — and they’re all jazzed up, despite having snatched only a couple of hours of sleep the night before. Christine plays Frankie’s current favorite pop song — Drake’s infectious “Fake Love” — on her phone, and they all dance for the camera. Frankie teases Emma about her “techno bounce,” and everyone grins.

After the photoshoot wraps, we all pile into Christine’s gunmetal Honda Civic to go get some much-needed coffee. In the backseat, Frankie and Emma run through selfie options; they upload group shots to the Discwoman Instagram whenever they’re all together. The most important thing is that they all feel good about the picture they decide to post, which, today, requires several minutes of review and discussion.

The Brooklyn street we eventually park on is a patchwork of asphalt and concrete and dirt, of trees and litter and chewing gum stains. The three women zigzag down it together, leading one another through the mess.