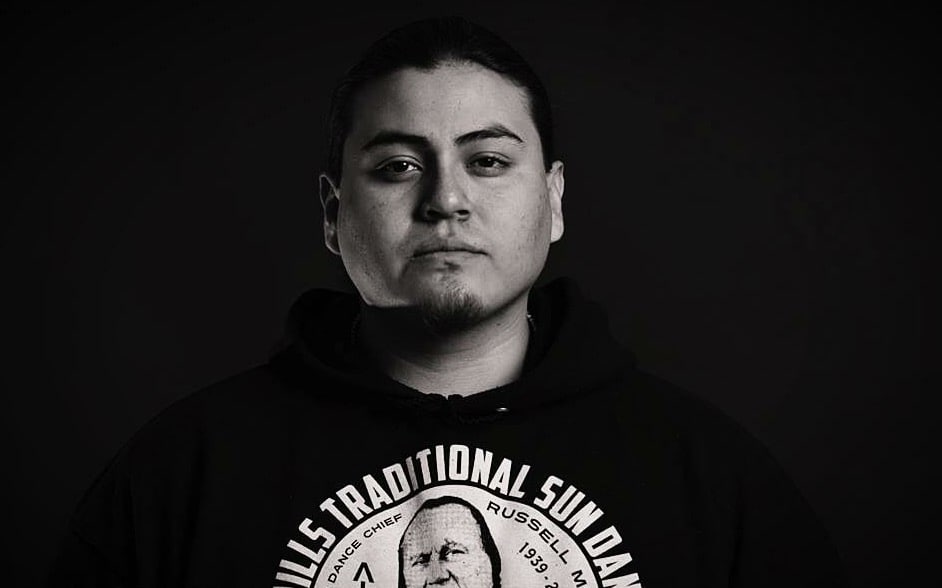

Nataanii Means

Photo by Terrance Clifford

Nataanii Means

Photo by Terrance Clifford

Nataanii Means, an Oglala Sioux and Navajo hip-hop artist and activist, dedicated his life to the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline. In August, he dropped everything to live on the frontlines in Cannonball, North Dakota, where he helped maintain the prayer camps housing thousands of water protectors and indigenous allies, demonstrated at construction sites with nonviolent direct actions against armed police, and used his platform as an artist to document and broadcast Standing Rock’s struggles.

“It’s been kind of hard, but it definitely has woken up the world to [indigenous issues],” the thoughtful 25-year-old tells me over the phone. After the fraught forced eviction of the Oceti Sakowin camp in February, Means looked to other forms of resistance. He began performing with a group of indigenous musicians brought together at Standing Rock. “You really find out who you can be close with when you’re living together in a yurt during a blizzard,” Means says with a laugh. With help from Anishinaabe environmentalist Winona LaDuke’s organization Honor the Earth, the group started booking their first shows for what has now become the Voice Of Water: Wake Up The World Tour.

The Wake Up The World Tour is one answer to the unjust end of Oceti Sakowin — its aim is to inspire further #NoDAPL resistance through musical expression. It’s also an outlet for the water protectors to process the camps’ events in order to heal and move forward. The tour comprises of live performances from Means, Dakota rapper/producer Tufawon, Oglala Lakota MC Witko, Blackfeet rapper Yaz Like Jaws and others as well as panel discussions surrounding Standing Rock and indigenous activism. “[Native] high school kids, they look at us like we're warriors and it's a crazy feeling,” Means explains with genuine awe. “It's really emotional, but we're just trying to give back to the community by sharing our words, whether it be with lyrics or laughter.”

The tour, which kicked off in British Columbia in March, is slated to cross the West Coast, Southwest, Midwest, East Coast and even the UK with dates stretching into September. The team is still actively booking dates and collecting donations to sustain the next chapter of their resistance. The FADER caught up with Means to learn more about the Wake Up The World Tour below.

The Oceti Sakowin forced eviction must have been traumatic. What were the last few days at camp like for you?

It was very high tension. There were things that we had to worry about at that time — the blizzards and police brutality — and it diverted our attention from the pipeline. We had to go through checkpoints constantly and were under surveillance by Morton County and by DAPL, and the paranoia from being under constant surveillance is traumatic. All of us have PTSD. When I hear helicopters or planes overhead, I get that feeling and I freak out. For a lot of us, hearing popcorn popping takes us back to that night on the bridge when they were just shooting rubber bullets at us.

On top of that, when the pipeline was being built, we were going out there and physically stopping it. We had to witness the earth being raped and our sacred sites desecrated which is also traumatic. So the last couple days were really hard.

How was the seed for the Wake Up The World Tour planted?

The people involved with this tour are all people that were involved at the camps and it just so happened that we’re all performing artists. A majority of us spent lived there for months — we were arrested together, lived in yurts together, hauled human compost together, did shows at the camp and took our studio equipment up there and made music together.

We experienced a lot of things in the [Oceti Sakowin] camp from the state of North Dakota, the federal government, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. There were a lot of misconceptions happening, but we saw it first hand — saw how the state of North Dakota was overrunning the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, how they were bullying water protectors.

So, we decided that when this thing does end and we're ultimately forcibly removed, we want to go on tour and tell our story and experiences — the beautiful parts as well as the things that are hard to talk about but need to be talked about.

“This tour is a good way to tell the truth about what happened at Standing Rock, tell the truth about an oppressive government, what it does with our tribal governments, and how they work hand in hand.”

Along with live performances, the tour incorporates question and answer sessions, and panels. Who are some speakers you’ve worked with so far?

For the tour, we sit down with different organizations and groups and talk about the #NoDAPL movement in open spaces. We also get to reconnect with other protectors that were at the camp and which is really beautiful.

We had a really great panel in Vancouver where we got to meet with these amazing protectors from the Unist'ot'en's Camp — they're Dene from Northern British Columbia. The thing with their nation is that they’ve never ceded their territories or signed any treaties. They're fighting a pipeline from Enbridge that's been trying to go through their territory for seven years now. They used a lot of nonviolent direct action to stop them — they put up a village right in the pipeline’s path and live there today. We got to hear their updates and what they have planned for the future. They're very experienced and really inspiring to be around and to learn from.

As an indigenous musician who has been on the frontlines of the #NoDAPL movement, what do you want to accomplish with the Wake Up The World Tour?

I like to say that this tour is a way of processing the experience and trying to get through it. When you talk about these experiences, they’re healing and freeing — it’s good to get it out there, out of yourself and into the open. But you also have to face them head-on again and that’s hard. After the eviction, we went to our ceremonies and medicine people to help us with these things and we've done the necessary protocol, but it's still really hard.

This tour is also a good way to tell the truth about what happened at Standing Rock, tell the truth about an oppressive government, what it does with our tribal governments, and how they work hand in hand. We want people to realize that this tribal government is from the federal government’s 1934 Indian Reorganization Act — they're not here to help us, they were placed in our communities to overlook us.

When it came down to actually doing something to stop the pipeline, tribal governments gave in. I feel like we lost. As young people that have to live in this world for its remaining years, it should be up to us what happens. So we're just trying to spread that knowledge and further the movement and further the hope. It's a real learning experience, and to be able to grow and be better and smarter people from this — that's my hope for the future.