GoldLink puts on for his hometown. Raised between Washington D.C. and Prince Georges County, Maryland, the ever-experimental artist has galvanized crowds around the world with a pulsating sound that he coined early on — future bounce. His last two releases God Complex and After That We Didn't Talk were sonically aligned with this style. With his new album At What Cost, GoldLink pivots in a new direction: he smoothes out the bright colors and turns the spotlight on D.C. culture and its distinct musical legacy.

Go-go music, which is sub-genre of funk created in the city by the iconic Chuck Brown in the 1970s, is the figurative backdrop for the project. Despite its evolution, go-go is deeply woven into the cultural fabric of the nation's capital and the bordering metro areas of Maryland and Northern Virginia. Across 14 tracks, GoldLink utilizes interludes, features, and lyrical references to neighborhoods as a way to peel back the textures of his city. In an interview at The FADER office last week, GoldLink explained of his hometown: "It almost shapes us as a community and who we are. It’s like the music is the background for the entire city."

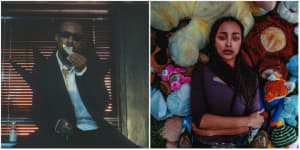

During his visit, GoldLink talked about how gentrification is affecting D.C., his responsibility to represent, and why he took a minimal approach to the album's production this time around.

At What Cost pays homage to your hometown. What has it been like for you, balancing these ideas of representing a city and evolving as an artist?

It's one and the same to me. The only thing I give a fuck about is the city. That's my purpose. If I wasn't from D.C., I wouldn't even have written a song. You understand? If the city’s proud, if I make it in the city that's all that really matters to me at this point in my career. If I could sell out 20 shows in my city and never sell out a show outside of the area, I wouldn't care.

The DMV is made up of Washington D.C., Maryland, and Northern Virginia. Where exactly were you raised?

I was born in D.C., then I was raised in Landover, Maryland. Then I was raised back in D.C. because I was playing football at Ridge Road, and I was playing at Marshall Heights. So, I was on the border of Maryland and D.C.. Then, my mother and father divorced so I moved from Maryland to Virginia when I was turning 16.

Gentrification is happening all over D.C. Does it feel different now when you go back?

Yes and no. It depends on what part. Of course it's "different," but it's the same as far as like the essence of the people and that'll never change. The kids still have the accents and they're still living and growing up the same way that we were raised. But the city as a whole, like, you're talking about politics and all the renovations that you’ve got to keep in consideration.

Did the impact of these new shifts in some way influence why you wanted to make this project, which revolves around the culture of the city and area?

Yeah because if I wasn't in the position to tell this story, then who was it going to be? And I felt like if it wasn't me, it would either be a kid that was coming after me, but it may be too late. It wasn't told by the niggas before me. I just felt it was my job. It's one of two ways it could go. It could jumpstart people giving a fuck and trying to change — I wouldn't say reverse it, but maybe adapt to it. They could also try to reverse it because anything's possible. Or people could give up. The fate is in the hands of the natives.

“I saw that I could go to other countries and realize that I only fit in where I’m from.” —Goldlink

You use go-go music as a symbolic focal point throughout the album. What's the genre's impact within D.C.?

Essentially, go-go is ours and we created it. We hold value to it, we hold it to the highest standard. Go-go means everything to everybody.

How has go-go impacted areas outside of the DMV?

It just depends on how you look at it. It starts in D.C. so for D.C. niggas, that's their shit. At the same time for example: I was growing up in D.C. too at a time when they were foreclosing shit. They were foreclosing whole ass apartments and knocking shit down, so a lot of us moved to Maryland. I was playing football at Ridge Road which was right on the border of Seat Pleasant, which is considered Maryland, but you could walk literally two minutes down the street and be in D.C. — I lived five minutes from that. So a lot of my friends from Northeast D.C., we'd go to school in Maryland and be at the basketball courts and they’d be like, "Hey, what the fuck is you doing here?" Like, "Nigga, I live right down the street." So, Maryland niggas still hold it down.

What's Maryland's role in go-go music?

The most popular venues were in Maryland. Crossroads is down the street from my house. Kentland’s firehouse is in Maryland. Even the band New Impressions is from there and that's a prominent go-go band. So for D.C. and Maryland? That shit means everything. For Virginia, they get it. They can appreciate it too. [Laughs]

The go-go shows stopped after a certain point. When was that and what happened?

In 2011, somebody got shot. That's when everything changed because go-go music wasn’t really apart of it anymore.

You shed light on some of those aspects of the culture on the album, especially with the ending of "Meditation."

I'm not trying to highlight go-go as a negative thing, because it's not. With go-go, a lot of killing came and beefing came because a lot of neighborhoods were divided so there was a lot of rivals. D.C., is such a tightly knit place that all the hoods were so close to each other. So that shit bled into school, that shit bled into churches, that shit bled into community centers. That shit started really fucking niggas up. When we were growing up we had niggas talking shit to each other on MySpace and on YouTube. That all came with the music.

I was losing my homies so quick that I appreciated life more. I cried on my 18th birthday because my friend had just got smoked that year before. But, there are lot of good things that came out of go-go. We went to the New Impressionz practice last week and they play music by ear. These are talented hood niggas who'll bust your fuckin' head but they’re so talented. So, I don’t want to just talk about the violence, I'm trying to talk about everything.

This album doesn’t have quite as much bounce as your previous ones. Tell me about what was different this time when you were creating the project and what producers you worked with.

Steve Lacy, Matt Martians, KAYTRANADA. Louie Lastik, and Taz Arnold are the main dudes. I tried to keep it futuristic, but I wanted to keep it minimal. I wanted to add a tribalism aspect so there's heavy drums and good instrumentation. It’s very minimal so you can focus on what I was trying to say and the message I was trying to get across while also keeping that texture of electronic music. Instead of what I did on my first tape God Complex which was use old-school samples to keep it nostalgic — I just relied on the music.

The tribal aspect is the best way I can explain D.C. if you’ve never been before. This is our hood and this is their hood. This is their tribe, and this is our tribe. This is the background music that we party and we love, fuck, and fight to. We're protective over our tribe and rep it so much.

You’ve emphasized that your lyrics all reflect your reality. On At What Cost, what’s your truth?

I’ve realized that I'm literally no different or more special than anybody else around me. I'm just a byproduct of the city I’m from. We all fuck up. We all get in trouble. We all talk the same. We all got in trouble growing up. I just so happen to be a regular-ass nigga who's able to just speak on everybody else's behalf. This album's been happening before I even understood because growing up and being able to have one mixtape that can help me tour the world, and a second one is crazy. I saw that I could go to other countries and realize that I only fit in where I'm from.